The man credited with creating Britain’s National Health Service is Aneurin Bevan, the son of a poor coal miner, born in Tredegar, Wales, in 1897. His father, David, along with two thirds of the men of the small, grim town in the South Wales valleys, worked down the pit where he contracted the familiar coal miner’s lung disease, pneumoconiosis. The young Bevan worked long hours for a local butcher when he was 11 years old, earning pennies the family needed. When he reached the age of 13, he went to work in Ty-Tryst colliery for seven shillings a week. That’s around €0.40; it was worth a little more in 1910 but it was still a pittance. Fifteen years later, Bevan’s father died in his son’s arms from the disease his mining work had given him. It helped to frame Bevan’s belief in the four principles for the new NHS following the Labour Party’s landslide victory in the 1945 general election: it should be free at the point of use, available to everyone needing it, paid for out of general taxation and used responsibly.

There was considerable opposition from the British Medical Association, representing doctors, from some of his Labour Party colleagues, but mostly from the opposition Conservative Party, the Tories of Winston Churchill. Bevan’s memories of poverty, mistreatment, overwork and the death of his father made him dislike the Conservatives intensely. “That is why no amount of cajolery, and no attempts at ethical or social seduction, can eradicate from my heart a deep burning hatred for the Tory Party that inflicted those bitter experiences on me,” he said in a speech in 1948, just two days before the NHS came into existence. “So far as I am concerned they are lower than vermin. They condemned millions of first-class people to semi-starvation.” And in words that could have been spoken during Britain’s recent election campaign he added: “Now the Tories are pouring out money in propaganda of all sorts and are hoping by this organised sustained mass suggestion to eradicate from our minds all memory of what we went through.”

It’s true that the days of mean, damp terraced houses, sometimes with four or more families sharing one outside earth toilet, are gone, thank goodness. Children no longer go out to work for pennies to augment their sickly parents’ meagre earnings. South Wales wasn’t alone in such experiences. In her book about Jarrow in North East England, ‘The Town That Was Murdered’, Ellen Wilkinson, the town’s first Labour Member of Parliament, wrote: “The poverty of the poor is not an accident, a personal fault. It is the permanent state in which the vast majority of the citizens of any capitalist country have to live.” Back in Victorian times, every summer saw vast numbers of deaths from disease in Jarrow with its overcrowded and tiny workers’ hovels. The medical officers appointed by the Town Council knew where the fault lay, even if the councillors weren’t keen to listen to them. But they pointed the finger of blame at the unwillingness of local entrepreneurs to try to clean up the town from which they drew their workforce. “It is not to be wondered at that the surface water is polluted when the ground around the houses is often saturated with the most foul liquid that drains from a privy midden” said a report by the medical officers. “This most foul liquid can be seen oozing through the walls and running according to the level of the ground either into the yards and beneath the houses or into the back streets.” But it took many years before anything was done about it; as Wilkinson put it: “The Council protected the interests of its members. A council consisting of property owners is hardly likely to take compulsory measures against property owners. A council of tradesmen is more interested in keeping rates (local taxes) down instead of providing services for its citizens.” It’s the sort of profit-driven capitalism mentioned by Friedrich Engels in his book “The Condition of the Working Class in England”, in which he describes the lives of children who were obliged to work as long and as hard as adults: “Many children complain: ‘Don’t get enough to eat, get mostly potatoes with salt, never meat, never bread, don’t go to school, haven’t got no clothes.’ ‘Haven’t got nothing to eat today for dinner, don’t never have dinner at home, get mostly potatoes and salt, sometimes bread’. ‘These is all the clothes I have, no Sunday suit at home.’” Engels also highlights the problems of England’s worst-paid workers at the time, the stocking weavers of Leicester, “earning six, or with great effort seven shillings a week, for sixteen to eighteen hours’ daily work.” The pay translates as €0.30 to €0.35 per week. Even allowing for inflation, that is less than a pittance.

FROM POVERTY TO WELLBEING AND BACK AGAIN

The story of Jarrow as stated by Wilkinson showed greed on the part of the coal owners, iron masters and shipyard moguls and a total disregard for the workers whose skills and hard work helped to make them and keep them rich. When the shipyard and steelworks closed in the 1930s, Jarrow suffered 80% male unemployment, which is why in 1936 some two hundred of the unemployed men marched to London in what they called the “Jarrow Crusade” to demand jobs and present a 12,000-name petition. They were not immediately successful but the march won support from some influential newspapers and helped to change attitudes, leading eventually to the post-war Welfare State and the NHS.

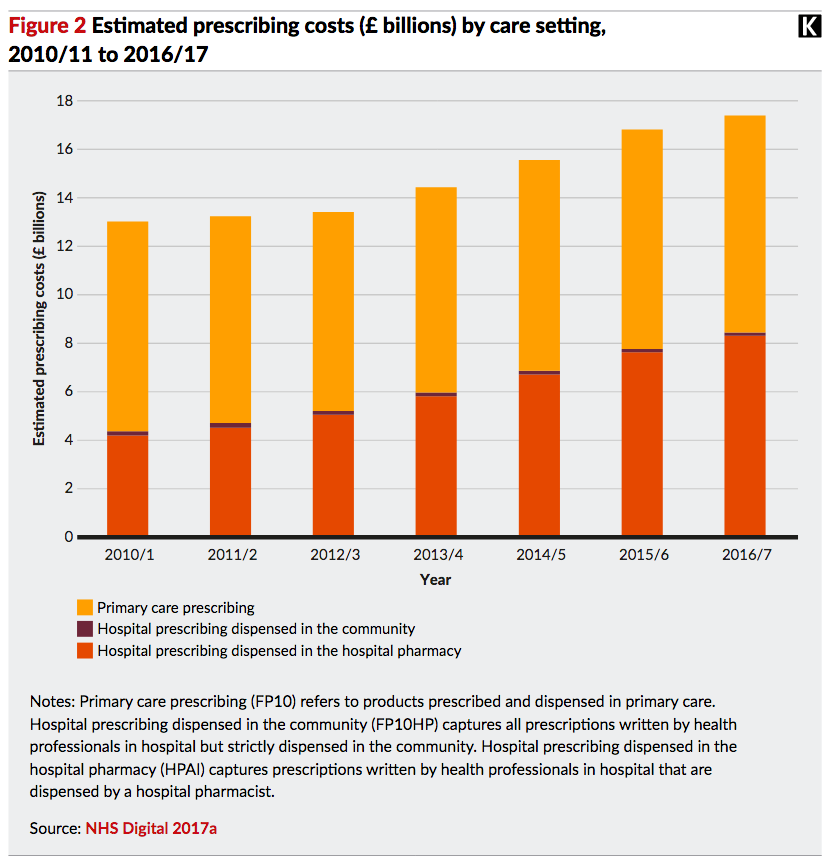

Mercifully, those days have long gone, although Jarrow remains a town of relatively high unemployment, and medical conditions have certainly improved under the NHS, even if Bevan complained that to win the grudging support of the doctors he had had to “stuff their mouths with gold”. So, more than seventy years on, what has gone wrong? There are several reasons. The NHS, in some ways, became a victim of its own success in a rapidly swelling population. More and more people have been calling on its services, often for very minor complaints. Many of the drugs, treatments and equipment have become increasingly expensive leaving NHS leaders to ponder who should be treated and what sort of financial limit should be placed upon the treatment on offer. When it was set up, the NHS could be funded – just – from taxes. It’s much more difficult now. In 1992, the Conservative government of John Major copied the idea of the Private Finance Initiative (PFI) from Australia. Under it, private companies are contracted to fund and run projects safe from the risk that a future, less sympathetic government, may cancel the deal. PFI deals have been used to build and run schools, hospitals and other facilities. They are buttressed around with cast iron guarantees, locking public authorities into contracts of up to 30 years for such things as cleaning and maintenance services, often at somewhat extortionate prices, and sometimes being required to continue paying for buildings that are no longer needed. As economist Vivek Kotechka wrote in a report for the London School of Economics: “This has meant that irrespective of the extreme budgetary constraints on local authorities and NHS Trusts, as well as the shrinking amount of money available for schools, hospitals and social care, they are still required to make annual payments to the PFI companies.” Kotechka writes that part of the burden of PFI debt should be taken away from individual trusts and be borne by central government. “One of the most pernicious aspects of PFI in the NHS is the extent to which local health economies are required to service high-cost loans effectively imposed on them by the Treasury as a means of keeping public sector investment off the nation’s balance sheet.” Kotechka is not recommending that PFI debt should be centralised; the cost of providing services and the cost of buildings would still be paid by the NHS trust benefiting from them. “However, the interest charge attached to the PFI debt under this proposal is capped at 3.5%, which is the borrowing cost of publicly-funded equity from the Department of Health and Social Care,” he argues. “With an average interest rate of 7% for NHS PFI schemes, this effectively halves the amount of interest paid by trusts, with the remainder being paid for centrally.”

The Conservative government’s Health and Social Care Secretary Matt Hancock promised that: “There is no privatisation of the NHS on my watch, and the integrated care contracts will go to public sector bodies to deliver the NHS in public hands.”

Health Andrew Lansley

© gov.uk.png

In 2012, the then Secretary of State for Health, Andrew Lansley, introduced a massive reform of the NHS aimed at cutting costs. The Chief Executive of the NHS at the time, Sir David Nicholson, described the overhaul as “big enough to be seen from space”, although the government assured the public that nothing would change from their perspective. England’s 152 Primary Care Trusts were replaced by 211 Clinical Commissioning Groups, as they were called. This put general practitioners in charge of much of the NHS budget, being assisted on the new CCGs by a hospital doctor, a nurse and a few representatives of the local community. Not everyone involved in healthcare considered that GP practices, effectively run as small businesses, had the experience to manage the multimillion-pound budgets required. Indeed, by also insisting that all health providers, whether public or private, must be regarded equally with no anti-competitive behaviour, the reform appears to ensure that private companies have equal access. And it allows disgruntled private health care providers to take legal action against the CCGs (and therefore against the NHS) if their bids are rejected, as Virgin Care did in 2016 when it failed to win an £82-million (€96.7-million) contract to provide children’s health services in Surrey. That way, instead of wasting money on costly drugs and treatments, the NHS could waste it in law suits brought by wealthy private health companies. Not everyone sees that as a step forward, even though Virgin came in for a lot of criticism and the episode did little to burnish boss Sir Richard Branson’s halo.

Matt Hancock © gov.uk

BUYING INTO, NOT BUYING

Those campaigning to keep the NHS to be the public service Bevan intended constantly draw attention to the creeping privatisation, or at least to the increasing use of private health care providers reaping a profit from public ill health. Even while Hancock was promising “no privatisation of the NHS on my watch” he was supporting a privately-run service in North London, GP At Hand, that is already spreading across the UK. It’s an on-line service, targeting younger, fitter and more internet-aware patients, leaving traditional GPs with older, less healthy patients with more complex needs, while the reduced number of overall patients on their lists means they receive fewer resources with which to cope. Commissioners at local level have continued to hand out contracts for a wide range of services, according to the lobby group Keep Our NHS Public, “including patient transport services, diabetic eye care (retinopathy), GP practice administration, elective surgery, community health care, and of course mental health care to private companies, many of them unreliable.” The same group cites the example of SSG UK Specialist Ambulance Support Limited which provided emergency and non-emergency ambulance transport for the NHS but which went into administration in September.

The idea of blatantly, openly selling off the NHS to private companies, however large, however prestigious, is a non-starter. The NHS is a sacred cow, held in holy high regard by the very people who moan about waiting lists and how long it takes to get an appointment with their GP. No-one would dare to sacrifice it on the altar of profitability, however sharp the knife and however fervent the belief in unbridled capitalism. However, parts of it have been sold off, at least in terms of putting some of the work out to tender and accepting bids from massive US health corporations, private equity companies and hedge funds. However, if we’re talking about the mental health sector we find that it has relatively little public sympathy. Need mental health care? Good luck with telling your friends and neighbours, who dismiss sufferers as loonies, hypochondriacs and just rather scary. Who cares what happens to them? The care of people in need of mental health care deteriorated under Margaret Thatcher, who sold off the large residential mental hospitals to wealthy individuals and corporations in the name of “care in the community”, which has often turned out to mean “lack of care on the streets”. Homelessness and rough sleeping have been on the increase across the United Kingdom with around 320,000 lacking a permanent place and some 8,000 sleeping in doorways or on park benches on any given night, according to the housing charity Shelter, far more than the government claims. That figure is thought to have doubled in the last five years.

According to the combined Homelessness and Information Network (CHAIN), an extra 50 people per day were made homeless last year every day and forced to sleep rough, a 50% increase on the previous year’s figures. The British Legion, which looks after veterans’ interests, believes that around 60,000 former military personnel are homeless or in prison. In answer to a written parliamentary question from the Welsh national party, Plaid Cymru, the government wrote that 25,000 veterans received treatment for mental health problems in 2016-2017, but according Ian Birrell, writing in the “i” newspaper, the Mental Health Foundation said that only around half ever seek help because mental health problems are hard to self-diagnose and embarrassing to talk about, putting the real number closer to 50,000. These are tough people who have put their lives on the line and would find an admission of mental ill health very painful, even if Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder is quite common. Again, Birrell reports that according to the Ministry of Defence, around 3% of those admitted to prison have been in the armed forces, giving a number of around 9,600, but the probation union Napo claims the proportion is closer to 8%, which would put the figure at more than 25,000.

TURNING A DISINTERESTED EYE

But if the public seem to take little interest in those needing mental health care, the same cannot be said of the large private health corporations, which have taken on business worth almost £2-billion (€2.36-billion) and are now providing almost a quarter of mental health beds while soaking up (claims Birrell in the “i” again) almost half the total NHS spend on child and adolescent mental health services. Under their kind aegis, these wards hold not only self-harming or anorexic teenagers but also hundreds of people with autism or learning difficulties who are locked up because there is insufficient support in the local communities. What’s more, they’re often locked up a long, long way from home which means family visits are, at best, few and far between. Running these hospitals is very profitable for the people owning these health companies, even if their front-line staff are on the minimum wage. Furthermore, the US ambassador to the UK, Woody Johnson of the Johnson and Johnson pharmaceutical family has said that more open access to the NHS will be part of any post-Brexit trade deal.

Acadia Healthcare, based in Tennessee, bought the Priory Group from a private equity firm in 2016 for £1.28-billion (€1.5-billion). In its last Annual Report, it gave the optimistic view that “Demand for independent-sector beds has grown significantly as a result of the NHS reducing its bed capacity and increasing hospitalisation rates.” It would appear that making profit from the sick takes priority over healing them in the eyes of the board and shareholders back in the US.

It owns 450 facilities in the UK, including 10 hospitals but although it was involved in detoxing celebrities like Kate Moss and Robbie Williams, it has come in for criticism, especially after an ITV documentary revealed how one teenage patient spent several weeks wearing nothing more than a blanket at The Priory Clinic in Ticehurst, Sussex. The scandal has led to Acadia’s owner sounding out buyers for the Priory Group, for which it hopes to get £1-billion (€1.18-billion). City of London experts think it’s unlikely Acadia will recoup its costs, especially as Priory was bought before the EU referendum, when the pound was worth rather more than it is today.

GRAB THE GOAT

Even so, Britain’s NHS remains a tempting prospect for health companies in the US and elsewhere. Why shouldn’t they seek to make a profit in the UK if the government makes it so easy for them? And why does the government do that? Because they haven’t a clue what they should do with people suffering mental health problems; if someone can come along and take that problem away, so much the better. But most doctors would agree that locking up people with autism or learning difficulties doesn’t help, although I suppose that at least they’re out of sight. And while they’re out of sight, a series of investigative TV reports have shown that they are often mistreated and abused. “In hospital you should get the very best care and treatment,” says Jordan Smith of Dimensions Health Equality. “You should get the right levels of food and medication and air and conversation. When you go into these places you are stripped of everything, it’s like they cut you in half and they lose half of you.” Dimensions, along with Rightful Lives, an initiative to highlight the human rights concerns of people with learning disabilities and autism, say that locking someone away for £3,000 (€3,537) a month is poor value for the NHS’s money and does nothing to help that person. “There are other ways to support someone to help them to get better,” says Smith, “like, instead of keeping them in rooms, giving them choices about where they want to live, who supports them and focusing on what they can do well.”

The NHS is, as I’ve mentioned, a sacred cow and the problem with sacred cows is that politicians are incapable of talking about them sensibly. Instead, they become more like the goat carcasses over which mounted Afghan tribesmen used to fight in the traditional game of buzkashi. The aim was to snatch the carcass from the ground while at full gallop and get it to one of two designated posts while others, riding equally furiously alongside, tried to snatch it away. You could cheer on the player of your choice, you could envy the winning riders, but nobody wanted to be the goat. So, we’re left with mere slogans, ignored by the general public simply because they’re so used to politicians talking nonsense and bad-mouthing each other’s policies that they no longer listen. A game of buzkashi would attract more interest, even though the goat in question is invariably dead. The media may make heart-wrenching documentaries about conditions in some health facilities but health is a big and complicated issue.

When my wife qualified as a State Registered Nurse in Newcastle in the 1970s, it involved a 3-year course, partly in the classrooms of Newcastle General, a teaching hospital, but most of the time gaining hands-on experience on the hospital wards, including feeding patients who couldn’t manage, bed-bathing those who couldn’t get out of bed and cleaning up the inevitable vomit or worse. That, of course, on top of chatting to them, checking temperatures, making sure they took their medications and so on. The Matron’s word was law and woe-betide any uppity surgeon who crossed her. It was all about compassion for the sick. Now, nurses need a degree, spend less of their training in practical work and most seem resolutely to refuse to clean patients up. The ward’s dedicated cleaners have been replaced by people on the minimum wage, working for outside contractors who don’t really care what happens as long as the bills are paid. Why should they care? Unless they have to go to hospital as a patient, of course. But on that score, public opinion seems more exercised about keeping foreigners away (presumably not including those working as doctors or nurses) than about how it all works. Aneurin Bevan must be revolving in his grave, although he may not have been surprised. Mendacity and greed were as common in his day as they are today.

For politicians, assuming a pro-NHS stance is always a sound policy. Those campaigning during Britain’s 2016 referendum for Britain to leave the EU claimed that it would free up £350-million (€413-million) a week to help fund the NHS. The figure was completely false and seems to have been plucked from the air, but even after it had been disproved repeatedly, Boris Johnson continued to quote it, although he sometimes denied doing so. More recently, he claimed that a plan to inject a further £34-billion (€40-billion) into the NHS would be “the biggest increase in modern memory”. He must have a short memory and believes (probably correctly, to give him his due) that others do, too. In real terms, it equates to an increase of £20.5-billion (€24.2-billion) between 2018/19 and 2023/24. But there was a larger cash injection made by the last Labour government of Tony Blair and Gordon Brown of £24-billion (€28.3-billion) over the period 2004/05 and 2009/10. Those who knew Johnson in Brussels (as I did – he was a neighbour and fellow-member of the media lobby) will not be surprised; he was never a man for detail. Or accuracy. He was carpeted more than once by the UK’s ambassador to the EU for writing totally untrue anti-EU articles for the Daily Telegraph. Johnson’s Conservative predecessor at No. 10 Downing Street, Theresa May, also claimed a “record investment” in the NHS But as the Victorian British prime minister Benjamin Disraeli said, according to Mark Twain: “There are three kinds of lies: lies, damned lies and statistics.” Most people don’t read the fine print on an agreement and they certainly don’t question figures employed by someone they support politically. Take Donald Trump, for instance. Do you believe him when, where the NHS is concerned, he says “Everything is on the table. So, NHS or anything else.”? This probably isn’t helpful to Johnson, but does it really matter? A recent opinion poll in the UK suggested more people trust Vladimir Putin than trust Donald Trump (and few people bother to read what Trump says or analyse its meaning). Or, for that matter, than trust Boris Johnson. So, even the use of Novichok in Salisbury is forgotten, along with the woman who died and the four people (only two of them Russian) who nearly did. It’s a strange old world.

DIVIDE AND DON’T RULE

Britain is strange in some ways because it breaks down into England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland and health provision is slightly different in each. For instance, in Scotland, all social care over the age of 65 is free. In Scotland and Wales, prescriptions are free, whereas there is a means-tested charge in England. Scotland also has different prescribing rules for drugs and medicines to the rest of the UK. The Scottish Medicines Consortium make decisions about the prescribing of drugs in Scotland, and has different timescales and priorities to NICE, which provides the same service to England, Wales and Northern Ireland. Wales normally follows the decisions of NICE but the All Wales Medicines Strategy Group may in some case make a different recommendation. According to the UK’s Multiple Sclerosis Trust, it means people with MS in Wales may have access to different drug options to those elsewhere in the UK. It’s different again in Northern Ireland, where the NHS is referred to as HSC, which stands for Health and Social Care. Like the NHS, treatment is free at the point of delivery but it also provides social care services like home care, family and children’s services, day care and social work as well as deciding policy and legislation for hospitals. It’s a mishmash, not so much like the dead goat used in Afghanistan’s buzkashi game; more like one that’s already been butchered into separate parts so that none of the tribesmen knows what bits to grab.

So where does all this leave us? The NHS as envisaged by Aneurin Bevan is virtually gone, rendered obsolete by rising costs, a swelling population, the PFI programme and the pricing policies of some pharmaceutical companies, but it still delivers health care “free at the point of delivery”, as he demanded. Maybe it does need a re-think but it certainly doesn’t need to be bought and sold by giant health conglomerates seeking wealth before health. I was very happy with the Belgian system when I lived there: you telephone for an appointment and in most cases your doctor answers in person; not all doctors can afford receptionists in Belgium and nobody expects them to run their practices for profit, like a corner shop. Yes, you pay for the visit and for the drugs prescribed, but everyone pays into a “mutuelle” – a health insurance company, most of which are attached to religious groups or political parties – and a large part of the cost is refunded. If you see a consultant, he or she is likely to give you their mobile phone number to ring if you need to speak to them. I can’t imagine this ever happening in Britain, where doctors tend to occupy ivory towers from which too many look down on their patients.

So, what’s the prescription? Well, it seems inevitable that private companies will have to provide some of the more specialised services where expensive equipment is required, but they should not have the right to charge exorbitant prices for it. Drug prices must be controlled, too. Britain does not want to follow America’s lead here. Certainly, a number of foreign companies have eyed opportunities within the NHS, which already spends some £9-billion a year on privately-provided clinical services, although that figure has remained fairly steady over recent years, according to the Nuffield Trust. But Trump has complained that Americans pay more for their drugs because Europeans pay too little. The American pharmaceutical industry agrees. In a blog for the Nuffield Trust, Mark Dayan writes of a submission by the industry to trade negotiators, complaining about the UK’s “long-standing market access barriers such as rigid health technology assessments, government price controls, insufficient health care budgets, and increasingly punitive and proactive national procurement initiatives.” In other words, the NHS should be more sympathetic to their shareholders and less concerned about health.

The US is famed for having the highest healthcare costs in the world, spending $3.5-trillion (€3.16-trillion) on it, averaging out at $11,000 (€10,000) per person or 18% of the GDP, up from 5% in 1960. It will go on rising, partly because of an ageing population, partly because of the development of costly hardware and very expensive drugs, but health outcomes are not as good in the US as in most other developed countries. The average life expectancy in the US is 78.6 years; the average for developed countries in general is 82.2 years with Japan coming out on top with 84.1 years. The UK’s figure is 81.2 years and few would agree that lowering it is a good idea. America’s experience gives the lie to the old adage that “you get what you pay for”. You clearly don’t. The best advice, in the UK or anywhere else, is don’t get ill.

T. Kingsley Brooks