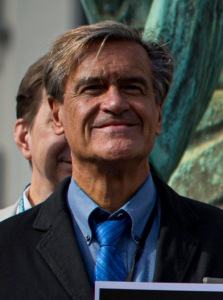

“We have had a bad experience, a bad historical experience,” Witold Waszczykowski told me when I asked him his thoughts on Vladimir Putin’s Russia, “and we consider that Russia has a very imperialistic policy that doesn’t recognise the security architecture that was developed after the end of the Cold War.” I don’t think too many people would argue with that analysis of where post-Soviet Russia stands with regard to Europe as a whole but especially those neighbouring countries where its writ once ran. Waszczykowski was speaking from personal experience, not just as a former member of his country’s Law and Justice government; he has spent half his life under Communist rule. Born in Piotrków Trybunalski, in Łódź Voivodeship, central Poland, in May 1957, Waszczykowski was clearly destined for political progress. He was an unusually intelligent child who went on to study at the University of Łódź, where he earned a Master’s degree in history. He then went on to the University of Oregon, gaining another Master’s degree, this time in international studies. After that, he travelled to Switzerland, where he studied at the Geneva Centre for Security Policy, finally returning to Łódź, where he gained a PhD in history.

In fact, it could be argued that Poland has received the raw end of virtually every kind of deal over the years. Under the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia had agreed to divide Poland between them, although both envisaged taking the entire country for themselves. Honouring treaties and agreements was never high on either regime’s list of priorities. The Nazis invaded first, on 1 September 1939, just a week after the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact had been signed, with the Soviets following suit on 17 September. For the Germans, it was to acquire what Hitler, in his infamous book, ‘Mein Kampf’, had called ‘Lebensraum’ – more space for the German people. That also implied, of course, the gradual annihilation of native Poles. That began almost straight away, once the Nazis had taken total power over ‘their’ part of the country, following the defeat of the Polish forces at the battle of Bzura and subsequently at the Battle of Kock. After that, both groups of invaders simply removed border posts that had formerly demarcated where their countries ended and Poland began. In the eyes of Hitler and Stalin, Poland had simply ceased to exist. It’s easy to understand why today’s Poles view both Germany and Russia with jaundiced eyes.

Can Russia ever be trusted to respect Poland’s borders and the sovereignty that is supposed to guarantee freedom and security? Perhaps not for many Poles. “Russia has a problem to keep to this security architecture,” said Waszczykowski, “I think Putin has two plans: a ‘plan maximum’ and a ‘plan minimum’. The ‘maximum’ is to come back to the position of the Soviet era back in the sixties, the seventies, maybe a little bit of the eighties, when his sovereignty was matched to the United States and the Cold War was ruled by this duopoly.” Neither option looks good from a Polish perspective. “’Plan minimum’, or should I call it ‘Plan B’, says Waszczykowski, “is to recreate a 19th century concept of power and to recreate the security architecture that is going to be ruled by mighty powers, including Russia. Russia doesn’t like the idea of cooperating with international structures such as the European Union or NATO or some other. No matter what we offer, how privileged its position, it still has its suspicions and Russia is probably being neglected.” Waszczykowski is convinced Russia would rather, as he put it, “kick some countries” and rule there instead.

When the Second World War ended, the Polish people were left with nothing. This comment by Janina Godycka-Cwirko from 1945, describing the immediate post-war Warsaw once the troops had left, is quoted by Anne Applebaum in her excellent (albeit terrifying) book, ‘Iron Curtain – the Crushing of Eastern Europe”: “It seemed to me that I was walking on corpses, that at any moment I would step into a pool of blood.” Long before they left Warsaw, the Nazis systematically destroyed the city’s architectural heritage, dynamiting its beautiful mediaeval buildings one by one, with German architectural experts advising them on which were the most important and must, therefore, be destroyed first. It’s something most people will find hard to believe or even imagine. It goes without saying that many of the city’s ancient books and paintings were destroyed, too, apart from the few looted to add to the collections of prominent Nazis. The Germans planned to remove Warsaw from the face of the Earth, replacing it with a purpose-built town created exclusively for Germans, with a nearby slave camp so that Poles could look after their needs. Of the original city, 85% was turned into blackened, burnt-out rubble.

BUILDING BACK, PLUS EXTRAS

The Poles may have many reasons not to like the Russians, either, but at least under Soviet rule, many of the historic buildings were reconstructed to match the originals that had been destroyed, much of the work being carried out by Varsovians themselves who had returned from exile overseas. To visit those parts of Warsaw today you would hardly know that so much of it is a post-war construction. Stare Miasto – Market Square – looks now much as it must have looked in the 18th and 19th centuries or even earlier. I bought a postcard there showing it as it is now and as it was just after the Nazis had destroyed it. Stalin’s big gift to Warsaw was the Palace of Culture, a huge and typically Soviet showpiece of a building, tall, imposing (if you like Soviet architecture), and visible all over the city and beyond. As I was returning to Warsaw from Krakow by helicopter once upon a time, my Polish cameraman glanced out of the window and commented to me: “We must be nearly home; I can see the Palace of Culture,” adding bitterly, “More’s the pity!” It is not a building much loved by Poles.

Waszczykowski is keen to remind me that Poland didn’t just turn its face to the West following the end of the Cold War and the collapse of the Soviet Union. “We started to be part of the West eleven centuries ago,” he reminded me, and being a highly-qualified historian, he should know, “when one of the first Polish rulers accepted Christianity and was baptised.” That was Duke Mieszko I, and his motives were perhaps more political than faith-driven. At the height of his power, Mieszko subordinated his kingdom to the papacy in the late 10th century, largely to guarantee its ecclesiastical independence from the German empire, which later became known as the ‘Holy Roman Empire’. This in itself is odd, because Mieszko already had a treaty with Otto I, the Holy Roman Emperor. Even so, it underwrote Poland’s sovereignty and was a step towards having imperial power in Poland. One of the turning points was an alliance Mieszko formed with Boleslaus I, the Duke of Bohemia and a member of the Přemyslid dynasty. He went on to marry the Duke’s daughter, Doubravka, and she may have been the one who persuaded him to accept baptism, although whether that was because she was a devout Christian or because she could see that it would boost his power we shall never know. Anyway, it made him, as ruler of the Polan tribe, an equal partner when he met up with other Christian leaders, so that was clearly a plus. His son Boleslaw I, became Poland’s first king.

“The Soviet Union’s domination after the Second World War was considered by Poles to be an aberration,” said Waszczykowski. “There was no discussion about the end of the Cold War, about a ‘Third Way’.” Waszczykowski clearly regrets that the opportunity was not seized by Poland’s leaders at that time to plot a new course for the country, re-establishing its independence and its sovereignty, assuming such a move could have been possible. In 1999, Poland started to “knock on the door” of NATO, as Waszczykowski put it, but “the US considered this a political membership”. Poland, however, has proved its worth as a full NATO member, and now hosts troops from other NATO countries, with whom Polish troops conduct frequent exercises. “So with this presence, this real presence of men and equipment,” Waszczykowski said, “we feel safer, and we feel right now that these are real security measures provided by NATO.”

THE ORCHESTRATED PROBLEM OF BELARUS

If anyone should have the experience to deal with tyrannical and – dare I say? – unreasonable leaders, it ought to be Waszczykowski. During his career he has been deputy Foreign Minister, then Foreign Minister of Poland, and he was also his country’s ambassador to Iran, whose leaders hold very different views about world affairs. So how should the EU deal with Belarus, which is pushing refugees across its border with Poland and refusing to readmit them, forcing Belarus’s neighbours to engage in what’s called “push-back”, which is not supposed to happen.

Right now, President Alexandr Lukashenko is more engaged with a shootout in Minsk between an IT technician opposed to his tyrannical rule and a member of the security service, still quaintly named the KGB. The technician had been posting anti-Lukashenko material on-line, which led to the KGB raiding his apartment. In the exchange of fire that followed, both the IT technician and the KGB officer were shot dead. In Lukashenko’s Belarus, merely expressing a negative opinion about Lukashenko is considered terrorism and Lukashenko has said he will “never forget” the people responsible. He wouldn’t last five minutes in the hurly-burly of Western democracy.

I asked Waszczykowski what should be done about Belarus and its continuing threat to Poland’s security. He recalled a meeting in 2008 between Putin and the then President of Poland, Lech Kaczyński, who died together with his wife and almost a hundred senior Polish officials when a Polish Airforce Tupolev Tu-154 crashed near Smolensk in Russia in 2010.

The cause has never been fully established, although dense fog may have played a part. Ironically, they had travelled to Smolensk to mark the deaths of hundreds of Polish military officers and intellectuals at the hands of Russia’s NKVD, forerunner of the KGB. It is generally referred to as the Katyn massacre, largely because that’s where the first of many corpses were discovered in mass graves, although the killings seem to have taken place not only there but also at Russia’s Kalinin and Kharkiv prisons. It had been a shocking act of mass murder by Stalin’s forces, showing that between the Nazis and the Red Army there was little to choose in terms of cruelty and brutality, even though ironically it was the Nazis who first found the mass graves and revealed details to the world in a bid to blacken the reputation of Stalin’s army.

At the meeting in 2008, President Kaczyński had made a prediction regarding Putin’s aims and ambitions: the recovery of all the territories that had formed the Soviet Union within his megalomaniac grasp.

“Today, it’s Georgia,” Waszczykowski said, “tomorrow Ukraine, then the Baltic countries, and then my country. And this prophecy is going on right now.” Indeed, it was Georgia back in 2008, as Tbilisi fought the Russian-backed breakaway regions of South Ossetia and Abkhazia. Putin was supporting them in the hope that a war-damaged Georgia would seek sanctuary in Russia’s arms. It didn’t. Georgia had declared independence from the collapsing Soviet Union in 1991 but Russia wasn’t keen to let it go. Putin, of course, is a puppet master, keen to let ambitious others do his dirty work to earn his favour. But Kaczyński has been shown to have been right. Ok, so how does that fit into the story of Belarus? Lukashenka was not part of that 2008 gathering (although Putin was there) but Waszczykowski told me he had been anticipating the sorts of issues now being thrown up on the Belarus border ever since. “We’ve been expecting these kind of trials ever since American troops pulled out of Afghanistan,” he said. “Putin is keen to test the commitment of NATO and America to the Eastern part of Europe.” Putin may be aiming his ‘tests’ at Washington, but Waszczykowski admits it is a worry, especially for Poland. “It’s a very, very dangerous situation,” he said, “because they are testing for this hybrid war and the commitment of Europe and NATO and of Washington especially.” Not that the EU is ignoring or forgetting the issues surrounding Belarus, even if the dispute looks increasingly like Putin setting traps for the West to see which way they will jump.

Lukashenko is an irritant for the west, which is why Putin and China’s Xi Jinping are keen to keep him in place. He is what Vladimir Lenin once allegedly described as “a useful idiot” (in reality the expression probably originated in Italy), willing to do unpleasant things for the advantage of others, whatever the cost to his own reputation. Now the European Parliament has voted to take action of its own. Belarus’s refusal to accept back refugees who have crossed into Poland is simply a bargaining chip. Lukashenko wants EU sanctions on Minsk to be lifted and will keep pushing back refugees until they are. But MEPs, among them Waszczykowski, called for firmer sanctions to punish the Belarussian leader. Waszczykowski’s colleague Anna Fortyga, also a Polish MEP and the Foreign Affairs Coordinator for the European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR ) group in the European Parliament, (both are members) detects the baleful hand of Russia behind it all. “In the case of Russia,” she told a full sitting of the Parliament, “we can even see incitement to the brutal suppression of Belarusian society.” She believes Russia has deliberately developed Belarus into a battlefield in its hybrid war against Poland, Lithuania and Latvia. “In the event of a hybrid war,” she warned the Chamber, “The EU must stop being naïve and clearly perceive aggressors and distinguish them from victims. The activity of Lukashenko is a crime that should be condemned in the international arena.” As the DW news website puts it, “The West sees Alexander Lukashenko as a pariah, Moscow sees him as a wildcard, EU MEPs want to see him on trial.”

Lukashenko may be basking in the knowledge that he has – for the moment at least – the backing of Moscow and Beijing, but he should perhaps not forget that from their perspective he is also dispensable. Were he to embarrass either Russia or China he would be gone in an instant and almost as quickly forgotten. Waszczykowski told MEPs that “it is not enough to ban flights for officials or impose limited sanctions, it is also necessary to implement a policy of non-recognition of Lukashenko, and instead grant opposition leader Svetlana Tsikhanouskaya a special status in the EU.” Given Lukashenko’s attitude towards any potential rival for his leadership, that may turn out to be something of a poisoned chalice for Tsikhanouskaya.

Lukashenko believes that just to question his right to rule merits the severest punishment. “We also need tougher sanctions that will affect Belarus’ policy,” Waszczykowski said. “Let us remember that Belarus produces, for example, fertilizers, which are exported to Europe. We should also suspend cooperation in various institutions, in culture and in sports.” So, put a step wrong, Lukashenko, and you could find yourself up to your neck in fertilizer.

DANCING IN MUDDY BOOTS

We should not forget, however, that there is corollary to this development. The European Parliament also voted to urge the Commission to apply its new ‘rule of law conditionality’ mechanism to Poland. This follows the decision by Poland’s Constitutional Tribunal that Poland’s Constitution has primacy over EU law. “If European legal acts are no longer accepted,” said Monika Hohlmeier, a German member of the European People’s Party group, “it is questionable whether Poland can still profit from the enormous amount of EU funding it currently receives.” Juan Fernando López ,a Spanish Socialist and Chair of the Civil Liberties Committee, went further: “This decision of a Constitutional Tribunal that’s subordinate to the PiS Government,” he told the House, “crosses the final border of EU membership and violates the founding principles of EU law.” It could be counted as a bold decision by the Tribunal, perhaps, but it may turn out to be a self-destructive one for Poland and its people. To a non-diplomat like me, it does seem strange to believe you can be a member of a club and yet feel that your personal opinions rate more highly than the club’s rules. It’s a bit like joining, say, a rugby club but choosing to believe the rule about “no muddy boots on the dancefloor” doesn’t apply to you. I fear that the club’s facilities could very swiftly be closed to you.

Throughout this article I have referred to the Belarus dictator as Alexandr Lukashenko, but it is also correct to spell it Lukashenka. Lukashenka would be the more correct spelling in Belarus, where in Cyrillic it is written Аляксандр Лукашэнка, while in Russian it should be Александр Лукашенко. I don’t suppose the man himself cares much either way, so I shall stick to the more commonly-used Russian version except where it is a quote. He may be more worried about what’s being said about his son in the latest revelations from the so-called Pandora Papers. Among the 12-million documents released to the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists is a claim that Lukashenko’s long-term ally, Viktor Sheiman, (once a Prosecutor General in his country and later sanctioned by both the EU and the US over the disappearance of several prominent critics of Lukashenko) has Lukashenko’s son Sergei as co-owner in a shady gold mining operation in Zimbabwe. The involvement of Sergei Lukashenko is extremely complicated and hard to follow, but it uses a shell company based in the UK. It has already been described, however, as ‘nepotism’ and a ‘conflict of interests’. As long as it is also stuffing the pockets of Lukashenko and son, we should not, perhaps, expect any action by authorities in Belarus.

DON’T SWIM ALONE AMONG SHARKS

From Poland’s point of view, neighbouring Russia is, together with its puppet states like Belarus, the greatest menace, but it’s not the only one. “I think that China is becoming the economic giant,” Waszczykowski told me, “and of course with its large economy it is bound to have an influence on others: Asia, Africa and to some extent also in Europe. The threat is not military, but as an economic giant.” Economic the threat may be, but it’s still a threat. “GCHQ would know what kind of technology it’s trying to slip into our economy to find out what we have and to get data,” warned Waszczykowski . There is also some concern over Chinese naval manoeuvres in the Baltic Sea, although an invasion of Poland or any of its neighbours would spark a global confrontation on a scale that is unlikely to favour Beijing in the longer term. “Sometimes I think that the attention and the care about China,” said Waszczykowski, “is some kind of substitute, because we cannot counter a Russian threat.” He believes that China could pose a greater security threat than most Western strategists imagine, including militarily, although it could all be part of Putin’s game plan. “Russia is playing clever, trying to lure us into this anti-Chinese mindset,” Waszczykowski warned. “Cooperation with Beijing is strong.

Putin is quite clever because he’s offering all this cheap energy and gas, and he’s offering to mediate between the West and China, but I think it’s a dangerous game with Putin.” The West would do well to recall the words spoken by Viscount Bernard Montgomery, the general who routed Rommel’s Afrika Korps in North Africa, in Britain’s House of Lords in 1962: “Rule one on page one of the book of war is: ‘Do not march on Moscow’. Tule two is: ‘Do not go fighting with your land armies in China’.” Perceptive, perhaps, but ‘Monty’, as he was known, would have also agreed with the PiS on the issue of the LGBTQI+ community.

International power struggles are not the only problem, however. The European Union itself appears to be coming apart, with the Czech Republic the latest to be talking about a referendum on quitting (would that be Czexit). “Yes, this is a growing concern in Warsaw and Poland,” Waszczykowski admitted, “because we were hoping that the whole project of the European Union would fulfil its promise of everything from economic cooperation to the free market, the common market, but over these last twenty years it has tended in a political direction, delegation, and even some policies of a hegemonic character with some countries, especially Germany.” Waszczykowski is critical of the EU’s direction, of the way it has become more ‘political’, especially its attempts to unite the various countries on a single set of rules, rather than permitting them to go their own way. “Especially the Tribunal of the European Commission,” he said, “which has been ‘crossing the border’ and is trying to dictate European law. It’s not just protecting the existing law in various countries but trying to dictate the law.”

I asked him what his advice would be to the successors of former German Chancellor Angela Merkel. “Frankly speaking,” he replied, “We’re not going to miss Angela Merkel, because it was a myth that coming from the Eastern part of Germany, she was sensitive to the East European issues, because she was not.” Waszczykowski told me that there had been recent revelations that Merkel had been running the EU in accordance with Russian sensitivities. “She was paying much more attention to Moscow, to Russia, than to the interests of the member countries of the European Union and NATO,” he said, and he’s not hopeful that the situation will change with Merkel gone. It is not a view widely held in Germany or much of the EU. The Elite News Press summed up reaction to her departure in the following encomium: “The Germans elected her to lead them, and she led 80 million Germans for 18 years with competence, skill, dedication and sincerity,” reads the article, which would seem to be somewhat at odds with the views of Waszczykowski. It continues: “During these eighteen years of her leadership of the authority in her country, no transgressions were recorded against her. She did not assign any of her relatives to a government post. She did not claim that she was the maker of glories. She did not get millions in payment, nor did anyone cheer her performance, she did not receive charters and pledges, she did not fight those who preceded her and did not dissolve her.” In fact, when she stepped down as Chancellor, millions of Germans went out on their balconies, onto the pavements outside their homes or into public gathering places and applauded her for six solid minutes. No former German chancellor has had such a send-off, and nor would any other EU national leader I can think of.

Incidentally, no tears over her departure were heard coming from the Kremlin, either. Hearing of the criticism, a spokesperson for the EPP group commented: “It is not surprising that Waszczykowski criticises Merkel as all the Law and Justice party politicians do with everything that comes from Germany or from Brussels. However do not be mistaken, Law and Justice belongs to ECR and not to the EPP. Outside the EPP, even some time inside the EPP, to criticise Merkel has been a sport during her 16 years of mandate. History has nevertheless reserved a place for her, something that will not happen with all those criticising her during all these years.”

However, Waszczykowski firmly ruled out the possibility of Poland following the UK out of the Union in what’s been dubbed “Polexit”. “For eleven centuries we have been part of the West, part of Western civilisation, part of Christianity, Roman Christianity, so it’s a natural part of Europe for us to live together.” I asked about the idea of creating a ‘European Defence Force’ (EDF), with Poland already heavily involved in NATO. Waszczykowski agreed that his country is devoted to NATO which he believes is an example of vital cooperation between Europe and the United States, but he also said: “We are not against the thinking of creating additional European defence if there is no duplication and no duplication of NATO military efforts and if there is no competition with the United States.” He stressed how Poland and other European NATO members had worked in close cooperation with the United States on several occasions. “Without the Americans we cannot resolve the Russian-Ukrainian conflict.” As for the proposed EDF, he wonders where the money is coming from and also pointed out that EU member states cannot even agree on what constitutes a threat. “No money, no funding, no political structure and no common definition of threat,” was Waszczykowski’s verdict.

Whatever he thinks about this defence force, Waszczykowski remains largely optimistic about the EU’s future. “I am optimistic because I survived the Communist rule,” he told me. “I am 64, so I’ve spent half my life under the Communists, and I was living there, I was hoping, I was waiting for the collapse of this structure. It happened, it was like a miracle, maybe because of the support of John-Paul II.” It seems fairly certain that John-Paul II and his successor, Pope Francis, would agree in principle with Waszczykowski and other PiS leaders with regard to the LGBTQI issue. Waszczykowski drew criticism for defining homosexuality as an ‘ideology’, although gay people I have known (of both genders) tell me the attraction they feel towards others of their gender was innate, not a lifestyle choice. The PiS is not alone in having a strong distaste for people who would identify as LGBTQI+, or simply as gay.

Waszczykowski accepts that Poland is out of step with many other EU countries. “I think we have an ideological struggle in Europe,” he admitted, “because the majority of European Union politicians, especially Western ones, belong to the liberal-left position.” This sounds like an acceptance that Poland’s attitude to people identifying as LGBTQI+ is a minority one. “We have a conservative government which is alternative in conception. Not only that, but our policy is a successful policy. Our government in the last six years was very successful in running and steering the economy, and in our social programmes in Poland.”

Waszczykowski is proud of his government’s electoral success, too, which is in any case incontrovertible. “Over the past six years,” he said, “we have won every election.” They have, too, so there seems to be relatively little popular support or sympathy for the LGBTQI+ community, but although nobody seems to be proposing a witch hunt, there is clearly a degree of homophobia in this strictly Catholic country.

But Poland has always been a country of surprises. During the war, its Scouting movement turned into a fighting force, the Szare Szeregi (Grey Ranks), to act as messengers, operate radios, carry out nursing and even take up arms in the Home Army. Fighters as young as ten or twelve fought and died, the survivors turning up in Soviet concentration camps long after the uprising had been crushed. The message would seem to be – and I’m sure Waszczykowski would agree – never underestimate a Pole.