I was in Strasbourg at the exact moment Britain ceased to be part of the European Union. I wasn’t there because of the EU but because of the Council of Europe, that much-maligned and (in Britain) misunderstood body that pre-dates the Treaties of Rome and of which, to the surprise and incomprehension of many British people, the UK remains a member. It was also responsible for the creation of the European flag, originally as its logo, three decades before the EU (EEC in those days) institutions adopted it. I went to bed that night a citizen of the European Union and awoke the next morning as merely a subject of her Britannic Majesty, Queen Elizabeth II. On that first day of non-membership, I travelled back to Britain expecting something to seem different, but it didn’t. The TGV train from Strasbourg got to Paris on time, after reaching a speed of 299 kilometres per hour, and I passed easily and quickly through electronic passport control at the Gare du Nord to board my Eurostar as if nothing had happened. In London, I boarded a British train homewards (it was much slower than the TGV).

Of course, everything is supposed to stay the same until the end of 2020, even though I have since discovered when renewing car insurance that the time I can spend driving across continental Europe will be, from the end of December 2020, restricted to 180 days a year and that I shall then need a green card for my car insurance to do so. Little changes, for now; more will doubtless follow and I’m sure most of those who voted for Britain ‘to boldly go’ off into the great unknown will not notice the difference affecting them even then, until they want to book a foreign holiday and discover that they need a visa and health insurance for it. No doubt, egged on by Britain’s largely Euro-sceptic (and often untruthful) media, they’ll blame the EU for that, too.

The myths perpetrated about the EU and designed to foster scepticism were very common; some of the silliest (such as a claim that all trawlermen would be forced to wear hairnets) were dreamed up by Britain’s current Prime Minister, Boris Johnson, when he was a correspondent for the UK newspaper, the Daily Telegraph. He considered it “a terrific jape”, he later said in an interview. Other daft claims he made included that “Brussels recruits sniffers to ensure that Euro-manure smells the same”, that the EU was saying snails are fish (they never did, of course) and that the EU wanted to standardise the size of condoms. He also claimed credit for making the then Commission President Jacques Delors a bogeyman in the British press. He did it for a joke and because it amused him (and pleased the Daily Telegraph) but it led to Britain leaving the EU.

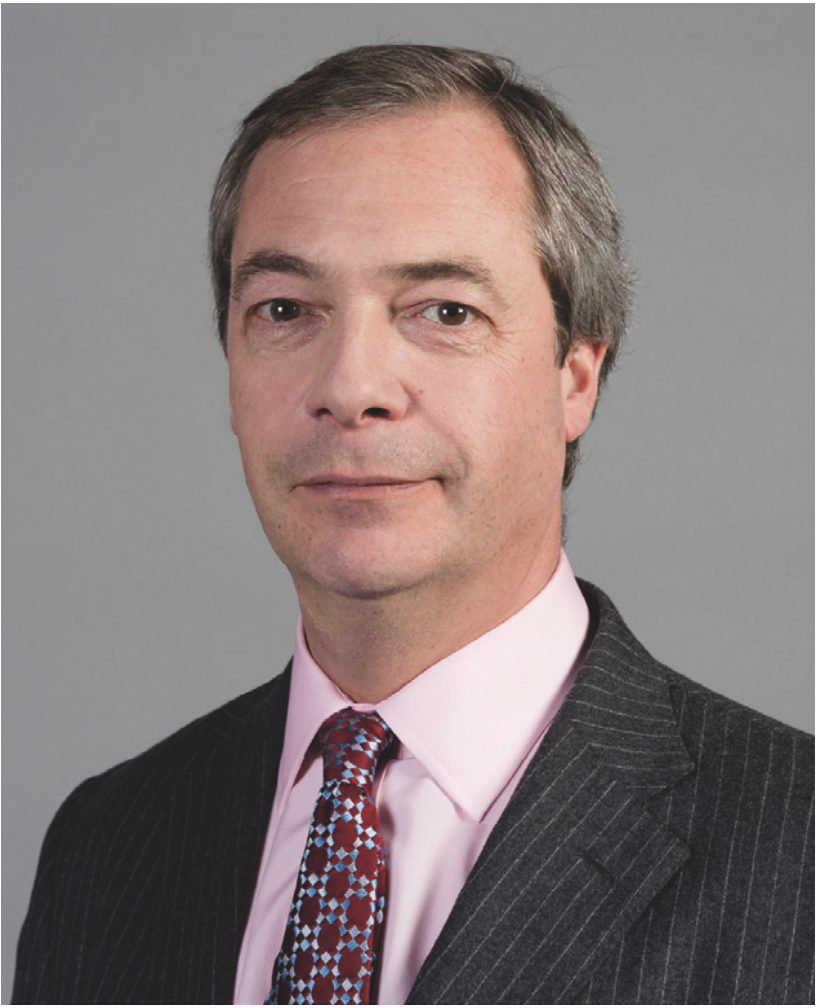

in 2009 © Wikicommons

Quite an achievement, if it was intentional. With Johnson, one can never tell. But because the stories were well-written and colourful (if totally or at least largely untrue) they proved popular with right-wing conservatives and Fleet Street editors, who told their own Brussels correspondents to follow suit. They found most EU stories rather dull and technical (they were, very often) so why not fill up the pages with nationalist fairy stories? After all, only foreigners were offended, and the British press has long had scant regard for them. Johnson told the BBC that it had been like throwing bricks over his neighbour’s wall and listening to the crash as they broke his neighbour’s greenhouse. A strange hobby for a prime minster, one might think, and not one likely to have found favour with Harold Macmillan, say, or Margaret Thatcher, nor with Disraeli nor the Viscount Palmerston (in Palmerston’s case he’d probably have sent gunboats and lobbed shells over the wall instead). Coincidentally, though, Johnson’s Daily Telegraph office in Brussels was in a street named after that notable Whig premier: Palmerstonlaan.

of the United Kingdom

© Wikicommons

PLUS ÇA CHANGE

On my last day in Strasbourg I was offered words of consolation by a great many people, including bar staff, waiters and shopkeepers: nobody wanted Britain to leave and invariably found a kind word (even a hug) for anyone British who shared their regret. At least I know I shall return to Strasbourg and be welcome.

So, what of the European Parliament? As a journalist, I covered it from 1986 to 2013, only missing a handful of plenary sessions in all that time. The departure of seventy-three British MEPs has made a difference, not only to the overall membership, which has gone from 751 to 705, but also to the political make-up. Of the seventy-three seats vacated by British MEPs, forty-six are being kept back for others who will come when more countries join the EU. The other twenty-seven have been shared out among fourteen existing member states which were thought to be under-represented. Of course, all these changes mean that the political groups have changed, too. In the European Parliament, MEPs do not sit according to their country but according to whichever political group they adhere to. The post-Brexit European Parliament would appear to be marginally more right-wing, reflecting, perhaps, the populism and nationalism that is slowly spreading across Europe and much of the rest of the world. Until the corona virus scare, Italy was absorbed with the 5-Star movement’s loss of support to far-right candidates. Now, the virus takes precedent.

After Britain’s withdrawal, the centre-right European People’s Party (EPP) grew from 182 members to 187, the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats (S&D) shrank from 154 to 147, as did the Renew Europe group (formerly the Liberal ALDE group), from 108 to 98. They suffered the largest loss. The Greens/European Free Alliance group (G/EFA) went down from 74 to 67, but the far-right Identity and Democracy group went up from 73 to 76. The European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR) dropped from 66 members to 61 and the Group of the European United Left/Nordic Green Left (GUE) went down by one, from 40 to 39. The group of non-aligned members, known as the ‘non-inscrit’, which had included Britain’s disruptive stunt-loving Brexit Party members, dropped from 53 members to 29 with their somewhat noisy departure. The leader of the Renew Europe Group, Belgian Liberal Guy Verhofstadt commented: “No-one will miss them”. The other, harder-working British MEPs will be missed, though, according to Seán Kelly, an Irish Fine Gael party member off the EPP group. “The UK will be a huge loss to the European Parliament, particularly for Irish MEPs,” he told me, “and it is a pity that they have now departed. UK MEPs were often our natural allies on certain major issues. On the occasions that I was rapporteur on a file, whenever I needed to build support, I would often go to UK MEPs and knew that they would deliver.”

A good day for the EPP, then, and bad news for moderates generally? Possibly not. The European Parliament doesn’t have a government, nor does any group ever have an overall majority, and the many issues it debates are decided on a simple vote; no one party has total control, despite the EPP being the largest group. “Although this is a marginal strengthening of the EPP and the far-right,” says former Labour Party and S&D member Richard Corbett, who is also an EU constitutional expert, “the fundamentals remain the same: this is a hung parliament where majorities have to be built issue by issue, through explanation, persuasion and negotiation among the mainstream parties, usually with a broad based majority emerging, sometimes with a centre-left one, sometimes a centre-right one, but never normally a right wing one. Remarkably, it works.” Corbett is right: no single group ever gets everything it wants. Compromise is essential. The Director of the Federal Trust, Brendan Donnelly, another former MEP who left the Conservatives because of their growing Euro-scepticism, highlighted one of changes since his time in the Parliament: “I remember that there was quite an effective centre-right majority made up of the EPP, the Liberals, the EDG and the Gaullists,” he told me, “I think it is possible that a new centrist coalition of the EPP, the S&D, the Liberals and some of the Greens may develop over time as a counter-weight to the radical Eurosceptic parties, who are now more numerous than before, but still have nothing like a majority.”

Parliament for the United Kingdom

© Wikicommons

That’s largely why Nigel Farage’s Brexit Party and UKIP before them relied on disruption rather than persuasion and a democratic vote to achieve their ends. But a sense of realism may have to prevail, according to Donnelly: “the need for an absolute majority of the Parliament to make the EP’s views count in dealings with the Council will probably be a powerful force for compromise and collaboration between these “establishment parties.” If the Council, with its variegated membership, can compromise in order to adopt legislative texts, the European Parliament may well find itself obliged to do likewise in order to maintain its relevance in the negotiations.” We shall see.

However, the new make-up of political power inside the European Parliament is reflected, none-the-less, in the reaction of MEPs to the European Commission’s new climate law. This aims to cut carbon emissions by 40% by 2030 but with the option later this year of increasing that target to 50% or even 55%, which is more than the EU signed up to under the Paris Agreement in 2016. It also aims for climate neutrality by 2050, a target described by teenage activist Greta Thunberg, who met the Commission and the Parliament’s Environment Committee, as “surrender”. She told MEPs they had to lead the fight against global warming. “Nature does not bargain,” she reminded them, “and you cannot make deals with physics. We will not allow you to surrender our future”. Her views were echoed by the United Left group, the GUE, whose co-president, France’s Manon Aubry, said “While humanity races against time to save our planet, the European Commission proposes a climate law that postpones setting a binding trajectory towards carbon neutrality and fails to address the root causes of climate chaos such as fossil fuel subsidies and free trade.” The EPP, on the other hand, clearly fears the law goes too far. The group’s environment spokesperson, German MEP Peter Liese, said “Even if we do only 50%, that is 10% more than we have committed to in Paris, and I don’t know any major economy in the world that’s doing such a big step, so we shouldn’t under-estimate the challenge to go from 40 to 50% in 2030 and that’s why it’s not wise to go to 55% without further analysis.” Concerns have also been raised about plans by the Commission to bypass Parliament when it comes to tightening emission targets. What is more, the EPP Group also wants other continents to make similar efforts to tackle global warming. And the EPP outnumber the GUE by 187 to 39, you will recall.

European Council President Charles Michel © Consilium.europa -European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen © Wikipedia – David Sassoli, President of the European Parliament, © Wikipedia

While I was saying a sad farewell to Strasbourg, with its white storks, bateaux-mouches and winstubs (small traditional Alsace restaurants or cafés where you can get wine, beer and local dishes), the leaders of the three main EU institutions were meeting in Brussels to discuss the future. They’d clearly discussed it many times before but Britain’s actual departure somehow concentrated their minds. Before that, a great number of people thought (and many hoped) it would never happen. But it did, of course. The three – European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen, European Council President Charles Michel and the President of the European Parliament, David Sassoli – announced their thoughts under the heading ‘A New Dawn for Europe’. Von der Leyen admitted, though, that the sun was setting on more than 45 years of UK membership. She spoke of “our fondness for the United Kingdom – something which goes far beyond membership of our Union,” going on to say “We have always deeply regretted the UK’s decision to leave but we have always fully respected it, too.” However, although the UK is leaving the political and economic club that is the EU, it remains part of Europe geographically. And, of course, as always (and as Johnson has personally discovered recently) divorce is never cheap. Britain must pay £33-billion (€38-billion) towards the projects it agreed to during its period of membership; all countries who held membership at that time must pay their share, even if Britain’s more rabid and right-wing newspapers urged the government to refuse to accept the bill. If they do, they know that Britain will not be trusted in any future deals. Eton-educated Johnson will surely know that a gentleman must always pay his tab.

PACK UP YOUR TROUBLES

In a speech to the London School of Economics (LSE), Ursula von der Leyen said that “without an extension of the transition period beyond 2020, you cannot expect to agree on every single aspect of our new partnership. We will have to prioritise.” However, it’s not at all clear that what Britain wants to prioritise is the same as what the EU might choose. Almost certainly not. For a start, look at Ireland. Throughout the three decades of the so-called ‘Troubles’ (1968 to 1998), the UK media too often took a simplistic ‘us-and-them’ approach to reporting. It was a frequent complaint of Northern Irish politician John Hume, of the Social Democratic and Labour Party.

The story was always far more complicated than those in mainland Britain realised, but the UK media – at least at its most popular level – doesn’t really ‘do’ nuance and subtlety. This was cowboys-and-Indians stuff, the good guys and the bad. Bang-bang, you’re dead, although the reality for those living in the North was less ‘Gunfight at the OK Coral’ and much more scary, unless you took it in your stride. A Sinn Féin councillor I met, long after the Troubles ended, told me how, as a teenager, he and others – Republican and Loyalist – had gathered in Ormeau Park in Belfast for what he cheerfully referred to as “recreational violence”. The British media failed to reflect this aspect of the situation and few commented on the fact that the International Hotel, where most foreign correspondents stayed, was bombed five times, while just across the road, the beautiful and splendid Crown Liquor Saloon wasn’t. If you’re ever in Belfast, you must visit it: Victorian brass-work, marble and polished mahogany. Oh, and they serve a very good Guinness, too. But it was where the leaders of the principle ‘terrorist’ organisations met from time to time in closed booths to discuss their differences and divide up the loot from their protection rackets, whilst raising the odd Jameson’s to each other. For many, it was a business, albeit a largely criminal one, as much as it was a fight for freedom. When the ceasefire was declared in 1994 (I was in Belfast at the time), serving members of the IRA found themselves no longer able to claim the bounty paid to its soldiers for a ‘hit’ – a bombing or shooting. It left them short of funds, which is why the numbers of ‘punishment beatings’ went up. OK, so you could no longer kill someone but the IRA and UDF commanders wanted to help their troops to pay for an upcoming wedding or funeral, or a new hat for the wife, so they looked back through their records to seek out those who may have betrayed them in the past. The killers were sent to break legs and arms, instead, thus earning the extra cash they needed.

German MEP David McAllister

© Wikipedia

Given the way England in particular had treated the Irish, the anger was hardly surprising. With Johnson’s plans to avoid a hard border between North and South, expect further fireworks. Already, the Scottish government is seeking clarification from Westminster over who will be responsible for implementing Johnson’s proposed ‘border in the Irish Sea’. The EU insists that Britain must address this issue before trade talks can begin in earnest. The proposal says that when the rest of the UK stops following EU rules on manufactured goods and agriculture at the end of 2020, Northern Ireland will continue to do so in order to prevent a border between the Republic of Ireland and the north.

What’s more, Northern Ireland will remain in the EU Customs Union, enforcing EU rules at its ports, which must mean customs checks between Northern Ireland and the rest of the UK, something Northern Irish politicians totally oppose. Indeed, Northern Ireland’s Agriculture Minister, Edwin Poots, has already told the Stormont assembly that Scottish ministers have refused to co-operate. The Scottish people voted to remain in the EU in the 2016 referendum and the Scottish government have said they will not permit infrastructure to be created in Scotland’s ports to enforce a border with Northern Ireland. Johnson has said there will be no ‘checks and controls’ between Northern Ireland and the rest of the UK, but EU negotiator Michel Barnier has said that with Johnson’s exit plan they are unavoidable.

According to the Belfast News Letter, MP Sir Jeffrey Donaldson of the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) has said that his party “will welcome any measures to ensure Northern Ireland businesses continue to have unfettered access to the UK single market”. He went on to say “Great Britain is Northern Ireland’s main market with 72% of all goods leaving Belfast port destined for Britain. An Irish Sea border will increase costs and will be bad for trade between Great Britain and Northern Ireland. The prime minister should never have conceded to the EU that a border could be placed in the Irish Sea.” Sinn Féin MP Chris Hazzard is afraid that Johnson’s government will ignore its promises to Northern Ireland and impose on it the border that it promised would not exist. He told the Belfast News Letter “While there is no such thing as a good Brexit, the protections secured in the Irish Protocol and Withdrawal Agreement offer some protections to local communities and businesses in the north. It now appears the British government is planning to ride roughshod over what has already been agreed; this would be completely unacceptable.” The row is, for now, largely confined to Ireland and Scotland. The last thing the people of the United Kingdom want is a return to headlines full of Brexit. Some may even be relieved that the media now seem preoccupied with the corona virus instead.

© Wikicommons

KEEPING IT LEVEL

The EU insists that its future relations with the United Kingdom must be fair, with equivalent rules on things like “social, environmental, tax, state aid, consumer protection and climate matters,” according to the European Parliament, whose members voted by 543 votes to 39, with 69 abstentions, for such an arrangement.

The aims are agreed on the EU side, according to German MEP David McAllister. “The European Union is united,” he said, “mutual trust and respect should prevail to ensure the best possible outcome for both parties. EU negotiator Michel Barnier and his team can count on the European Parliament’s full support”. From the EU’s standpoint, the interests of the remaining 27 member states are of greater importance than the interests of the one choosing to leave. “As stated in our latest resolution,” said McAllister, “the EU must do its utmost when negotiating with the UK to guarantee the European Union’s interests. We take note of the UK’s mandate published on 27 February. Members reiterated in their resolution their determination to establish a future relationship with the UK that is as close as possible, noting nonetheless that this will have to be different from that enjoyed by the UK as a member state of the EU.”

Dubravka Šuica, Vice-President

for Democracy and Demography

at the European Commission

© Wikipedia

The EU says relations must be based on a level playing field, but British government ministers seem to be digging divots out of it and casting doubt on any future trade deal at all. That sort of talk plays well with a British electorate that voted for a populist, right-wing government, just to ensure the UK’s exit from Europe. But right-wing populism is not a single tendency; it has many faces and they are different in each country. Europe’s increasing tendency towards xenophobia has been partly – perhaps even mainly – stoked by fears over immigration. Now, with Turkey having opened its borders towards Greece, there has been a surge; refugees from Idlib are starting to arrive where they are not, by and large, welcome. There have even been reports of shots being fired at life rafts carrying men, women and children towards the Greek border.

Greek MEP Kostas Arvanitis angrily commented “This is not our Europe! The Europe we know stands firm in solidarity with Greeks and refugees, resolutely in favour of the implementation of International Conventions, active in the protection of fundamental, human rights.” It’s not certain, though, that that is still the case. People are also turning away from political cooperation in other fields, too, in favour of a narrow nationalism that rejects other countries’ points of view. That, perhaps, is what fuelled the vote in Britain’s 2016 referendum, although it was the issue of immigration that seemed to bother the public more. Other far-right movements have sprung up across Europe, from Germany’s Alternativ für Deutschland (AfD) to Fidesz in Hungary, Italy’s Lega Nord and Poland’s Law and Justice Party (PIS). All reject the kind of collegiate thinking that marked the EU in the 1980s and 90s.

Winston Churchill who once said: “The best argument against democracy is a five-minute conversation with the average voter” Photo source: Yousuf Karsh. Library and Archives Canada

HUDDLED MASSES, GO HOME

America has seen Donald Trump’s rise to power, boosted by right-wing populist Steve Bannon, among others. It has accelerated anti-immigrant rhetoric and during his watch, hate crimes have increased; Trump seldom condemns such actions or else accuses the victims of sharing the blame for it. In India, Narendra Modi has pushed his nationalist Hindu agenda, posing a risk to non-Hindus and threatening to abandon secularism. Twenty or thirty years ago, the voices favouring division in the world were relatively few and isolated; that is no longer the case. According to Reporting Democracy, which is run by the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network, “illiberal populists in Central and Southeast Europe defended their ground or made gains in 2019, undermining democratic norms even in the face of mass protests.” The information comes from the independent human rights group, Freedom House. As Reporting Democracy writes on its website “From Czech Republic and Poland to Montenegro and Serbia, populist regimes defied civic pressure and continued to chip away at principles of liberal democracy,” quoting the latest annual Freedom in the World report from the New York-based NGO, Freedom House. Poland is accused of using tax-payer-funded media to get its message across to voters, denying a platform to opponents while seeking to rid itself of uncooperative judges. And in the Balkans, authoritarian regimes continued to make it hard to hold power to account, it found. “In Montenegro and Serbia,” writes Reporting Democracy, “independent journalists, opposition figures and other perceived foes of the government faced ongoing harassment, intimidation, and sometimes violence. Public frustration with the entrenched ruling parties boiled over into large protests in both countries, but they failed to yield any meaningful change.” Freedom House’s report makes depressing reading for those who hoped Europeans would march smilingly into the future, hand-in-hand.

“The report shows clearly once again, democracy is in decline,” said Mike Abramowitz, president of Freedom House. “Political rights and civil liberties are threatened in free societies and repressive ones alike. It is possible to turn the tide on this trend, but it is going to take concerted efforts from governments, pressure from the people, and partnership from the business community.” Good luck with that, then.

Meanwhile in the European Parliament, following Britain’s referendum, Nigel Farage, then leader of the UK Independence Party, reminded fellow-MEPs that he’d once told them he would lead Britain out of Europe and they had laughed. “I have to say, you’re not laughing now,” he quipped. They weren’t, either. He was right about leaving but not about leading the party that would achieve it; that task fell to an old Etonian who had lived and worked in Brussels, amusing himself and building a reputation by making up anti-EU stories the British media (and sections of the public) liked, and which successive British governments were forced to rebut, even if those rebuttals were seldom printed in the offending newspapers or, indeed, at all.

MY COUNTRY, RIGHT OR FURTHER RIGHT

According to the Pew Research Centre, although most populist parties in Europe differ on points of detail, most (but not all) share a dislike of the European Union itself. If the parties represented in the European Parliament see that trend as a vote winner, they will inevitably be tempted to reflect that in their voting patterns. Looking at Germany’s AfD, for instance, only 42% of its supporters have a positive attitude towards the EU, while 76% do not. With France’s right-wing National Rally (formerly the Front National), only 29% favour the EU while 58% are opposed. The trend is fairly universal but not exclusively so. Take Hungary, for instance. It holds up – just – for the ruling Fidesz party, with 62% favourable towards the EU and 73% opposed, but not for the other nationalist party, Jobbik, which used to have a uniformed militant wing and spout xenophobic slogans. With them, 82% now favour the EU and only 66% have a negative view. Much the same is true for Slovakia’s OLaNO, 84% of whose membership likes the EU while 64% don’t. Yes, I know the numbers don’t add up to 100%; they just give a general idea of attitudes among the parties’ supporters. Interestingly, in each case, supporters of far-right and populist parties have confidence in Vladimir Putin to represent their interests on the global stage. In the Czech Republic’s Freedom and Direct Democracy party, 61% have faith in Putin and only 24% don’t. The PVV party in the Netherlands has a 32% support for Putin against just 19% of doubters. Even in Britain’s formerly-influential UK Independence party, 34% had faith in Putin and only 22% didn’t. These are people who campaigned to get out of the EU because they didn’t trust it, but they trusted a man who ordered the murders of a former spy and his daughter on British soil, accidentally killing a British citizen in the process. Don’t you find that just a little bit odd? It was Winston Churchill who once said: “The best argument against democracy is a five-minute conversation with the average voter.” That is, if you can find an average voter.

In January this year, the European Commission set out its ideas for shaping the Conference on the Future of Europe, which should be launched on what Europhiles refer to as Europe Day, 9 May 2020, the anniversary of Robert Schuman’s declaration that launched the European Coal and Steel Community that would one day evolve into the EU. The Communication adopted is the Commission’s contribution to the already lively debate around the Conference on the Future of Europe – a 2-year project announced by President Ursula von der Leyen in her Political Guidelines, to give Europeans a greater say on what the European Union does and how it works for them. Von der Leyen said “People need to be at the very centre of all our policies. My wish is therefore that all Europeans will actively contribute to the Conference on the Future of Europe and play a leading role in setting the European Union’s priorities. It is only together that we can build our Union of tomorrow.” That does, of course, rely on a certain amount of cohesion that, seen from some angles, looks rather frail and insubstantial at the moment. Remember, the last European elections, while enjoying a higher-than-sometimes turn-out, returned a lot of Eurosceptic MEPs.

Dubravka Šuica, Vice-President for Democracy and Demography at the European Commission, stated: “We must seize the momentum of the high turnout at the last European elections and the call for action which that brings. The Conference on the Future of Europe is a unique opportunity to reflect with citizens, listen to them, engage, answer and explain. We will strengthen trust and confidence between the EU institutions and the people we serve. This is our chance to show people that their voice counts in Europe.” They may take some convincing. On Europe Day, the institutions throw open their doors and invite in the public, but it’s noticeable (and regrettable, in my view) that nearly all the people who turn up to have a nose around at the European Commission and the Parliament in Brussels are Belgians who don’t have to travel far. In Strasbourg, it’s mainly the French and a few Germans from just across the Rhein.

It’s that ability to cross borders without a thought that British people don’t seem to see as important. Many I’ve spoken to don’t think twice about travelling from England into Scotland or Wales but can’t understand why somebody in France should want to take a train to Germany or Italy. UK visitors to Brussels are often surprised to see destination boards in Belgian stations showing Moscow or Istanbul. “I can’t understand why anyone would want that,” commented one Eurosceptic Brexit supporter to me. There’s no point in arguing with someone who prefers narrow horizons to wide ones. It’s hard to predict how the new European Parliament will shape up, what attitudes it will take. Anyone who has ever sat in on a European Parliament committee meeting will have heard the high level of technical knowledge displayed. It never ceased to impress me. Don’t expect miracles from the Conference on the Future of Europe; there are unlikely to be any. But the EU will undoubtedly move forward without its British contingent. It’s just hard to know if it will veer right or left. Probably right, on balance.

Anthony James

Click here to read the 2020 April edition of Europe Diplomatic Magazine