Visit of Pope Francis to South Korea in 2014 © Korean Culture and Information Service (Jeon Han)

In 2014, US president Barack Obama and Cuban leader Raul Castro formalised the historic rapprochement between their two countries and took the opportunity to thank Pope Francis for his crucial mediation.

The following year, in the midst of the presidential campaign in the Philippines, Rodrigo Duterte who went on to win the presidency in 2016, called the pontiff a “son of a bitch” for causing traffic jams in central Manila during a visit.

Finally, in 2017, Pope Francis, already winner of the Charlemagne Prize which rewards ‘the most valuable contribution to understanding in Europe’, brought together the heads of state from all over the European Union in the Sistine Chapel, on the occasion of the sixtieth anniversary of the Treaty of Rome.

Three years, three issues and three different venues, but yet one thing in common: Pope Francis appears here more as a head of state, with wide experience in diplomatic practice than as a spiritual guide.

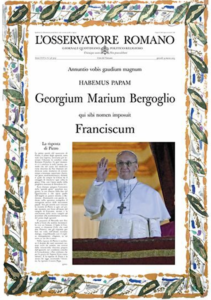

Indeed, since the election of the Archbishop of Buenos Aires to the throne of Saint Peter on 13 March 2013, Jorge Mario Bergoglio, renamed Francis, has revitalised the diplomatic activity of the Vatican which has also seen increasing media coverage.

The first Latin American pope, the first Jesuit pope and the first non-European pope since Gregory III in 731, the Argentinian who nicknamed himself the ‘Pope from the end of the Earth’, acceded to the papacy following another unexpected event; the renunciation of his predecessor Benedict XVI, something that had not happened since Gregory XII in 1415.

His extra-European and multicultural origins – as the son of Italian migrants settled in Argentina – as well as his conditions of accession at the head of the Roman Catholic Church with 1.3 billion faithful, enabled him to renew and re-direct papal diplomacy.

More emphasis was given to the millions left behind by globalisation and ultraliberal capitalism, to ecology and the plight of migrants, while maintaining and even strengthening the role of mediator and peacemaker, characteristic of apostolic diplomacy.

A UNIQUE DIPLOMACY IN THE SERVICE OF A ‘MORAL POWER’

In order to fully understand all the challenges of papal diplomacy, one must bear in mind the specificities of the pontifical diplomatic apparatus which maintains a diplomacy unique in its kind that is also perfectly suited to the Vatican State, also unique in its kind.

It is clear that the Vatican City State does not have the traditional attributes of power.

The smallest country in the world with an area of 0.44 km² and a population of 799 inhabitants, the Vatican with its 135 Swiss Guards also has the smallest army in the world.

So much for the bare facts. In matters of law however, a distinction must be made between the Vatican City State and the Holy See or Apostolic See. The former is an elective, absolute monarchy, while the latter refers to the government of the Catholic Church, headed by the Pope, who is therefore both head of state of the Vatican and spiritual leader of Catholics.

However, while the Vatican City State is quite a negligible power, this is not at all the case with the Holy See, which has moral authority over nearly 1.3 billion faithful on five continents. Legally therefore, it is the Holy See that represents the Vatican State on the international stage.

The existence of the pontifical territory dates back to the 8th century, when the king of the Franks, Pepin the Short gave Pope Stephen II some of his conquered lands to confirm their alliance. After centuries of intervening in the affairs of the peninsula, the creation of the Vatican State did not take place until 1929, with the signing of the Lateran Agreements between Benito Mussolini and Pope Pius XI.

Consequently, Catholicism became the only denomination to possess a sovereign and independent state, and therefore to benefit from an official status in the field of public international law.

This reduction in the size of the pontifical territory allowed the management of the Catholic Church to be ‘de-Italianised’ as it were. The pontiff, who no longer had any particular interests in the Italian peninsula, could devote himself fully to his universal mission – katholikos in Greek – embodied in the various papal journeys since Pope Paul VI (1963-1978).

Freed from competition between nations, the Pope does not seek to strengthen the influence of his state around the world, and this is what makes his diplomacy so specific. It is the only case of an entity subject to international law that specifically pursues religious and moral goals.

Since he is not accountable to voters, the pope enjoys great freedom of action. Having no specific interest, the Holy See is a neutral state, uninvolved in the geopolitical game.

This explains why it requested a seat only as an observer, and not as a member, at the United Nations in 1964.

Nevertheless, the Holy See is a major diplomatic power, and has thus significantly contributed to shaping today’s diplomacy. As early as the 15th century, the first permanent ambassadors to the courts of Europe were envoys of the Pope, known as nuncios.

Today, it is the Secretary of State, a kind of Minister of Foreign Affairs, who is the Vatican’s second in command.

Diplomacy is therefore part of the DNA of the Holy See, which maintains diplomatic relations with 183 countries, including the Palestinian Authority. Only 13 have refused to do so; most of these are strict Muslim countries (Afghanistan, Saudi Arabia, Brunei, Comoros, Maldives, Oman and Somalia) or communist states (China, North Korea, Laos and Vietnam).

But even in these countries the Vatican has an apostolic delegate who watches over the Catholic minorities present, such as in Brunei, Comoros, Laos, and Somalia. What’s more, negotiations are underway with China and Vietnam.

The Holy See is also a member of, or has observer status in many important international organisations, including the IAEA, UNHCR, OSCE, UNESCO, WTO, OAS, AU, etc. which allows it to participate in debates and to bring a spiritual and moral dimension to the discussions, while avoiding a real political commitment.

This means that it is listened to by all the international actors, who also appreciate its discretion.

A MEDIA PHENOMENON

This is the most visible characteristic of the pontificate of Francis, who, with his smile and humble manner, immediately won over the media. The press did not get along very well with his predecessor Benedict XVI, who was considered too rigorous.

It is precisely in order to counter a press that is sometimes not very lenient that the Vatican has developed its own media.

Other than the traditional media such as L’Osservattore Romano newspaper which has been published in eight languages since 1861, there is Vatican Radio, which was created in 1931 and which now broadcasts in forty languages. This is often the only link between isolated Christian minorities and the rest of the Christian world. The television channel, Vatican Media was set up by John Paul II in 1983.

His successors have continued to adapt the Holy See to the media of the time. In 2011, Pope Benedict XVI opened the Vatican News website, before inaugurating his twitter account @pontifex the following year. Anxious to communicate directly with the faithful, Francis followed suit, creating his Instagram account in 2016. And it works. On Twitter, the pope is the third most followed political leader with fifty million followers behind Donald Trump and Indian Prime Minister, Narendra Modi. On Instagram, he is the eighth most followed personality with seven million followers.

The ability to bring people together is indeed the key to his popularity. He speaks about human rights, solidarity, exploitation, ecology, globalisation, immigration.

This unifying speech appealed to a press in need of a positive and charismatic leader, to the point that the influential newsmagazine Courrier International headlined in March 2017 “François, the last leftist”.

With his very powerful speech on migrants and his strong commitment to ecological issues as illustrated in his ‘Laudato Si’ encyclical letter in 2015, the Pope has imposed himself as the last truly influential figure of the left in a world dominated by populists.

But Francis’ socialism could be seen as essentially an illusion, as the Pope heads a Church that still prohibits condoms, divorce and abortion, hence the Spectator magazine’s bitter comment: “Francis the illusionist”. It is clear that the media enthusiasm has gone a little overboard.

If the title of ‘Fourth most influential man in the world’ awarded by Fortune in 2015 or that of Personality of the Year by the Times in 2013 can be justified, it was more surprising to find the Pope on the cover of the American magazine Rolling Stone, which is more accustomed to rock stars, with, what’s more, a headline in reference to Bob Dylan: “The times they are a-changin”.

And in February 2017, on the cover of the Italian Rolling Stone this time, with the headline “Francis, the pop pope”. Even more astonishingly, in 2013, Esquire magazine named the Pope as the best-dressed man of the year, even though he wears the same cassock with worn-out sleeves all year round and orthopaedic shoes.

But the pontiff is aware of the risks of media over-exposure and is not exempt from blunders, at a time when paedophilia, as well as other negative societal phenomena may be threatening the credibility of the Church’s word.

BUILDING BRIDGES OR MAKING A DEAL WITH THE DEVIL?

As Vatican diplomacy is traditionally one of consensus, Pope Francis refuses to exclude any one actor, which leads him to negotiate with sometimes unsavoury political regimes that are often vilified by Western governments.

But the work of the Holy See is above all to strive towards a reduction in international tensions, in order to build peace. This activity can be seen in three main areas: the Holy See’s mediation efforts, the promotion of nuclear disarmament and interreligious dialogue.

In fact, ever since Pope Alexander VI divided the New World between the Spanish and Portuguese in 1493, mediation has been a constant feature of papal diplomacy, perceived as impartial.

And there are countless international issues on which the Pope has weighed in to avoid conflict.

In April 2020 for example, Pope Francis implored, on his knees, the leaders of South Sudan to reconcile and work for peace after five years of civil war. Francis is no stranger to spontaneous, genuine and gratuitous outbursts that can open a breach in the peace process and break diplomatic deadlocks.

Another bold proposal was the cancellation of the debt of African countries, which are struggling with the Covid-19 pandemic. Although the proposal came from Senegalese President Macky Sall in March 2020, the Pope’s Easter message on 12 April hastened its implementation.

The next day, it was mentioned by French president Emmanuel Macron, before the G20 finally agreed on a moratorium on the subject.

The pontiff also made a big splash by opposing the Western air strikes in Syria against Bashar Al-Assad as part of the EU’s plan to combat terrorism. In 2013, he organised a day of prayer in St. Peter’s Square against the bombing which was eventually abandoned.

He considered that strikes would have only aggravated the circle of violence and delayed negotiations. He is also particularly concerned by the conflicts on the American continent.

In Colombia for instance, he worked hard to facilitate negotiations between the government and the FARC, which led to an agreement in 2016 and the disarmament of the paramilitary group. And his trip in 2017, during which he met with 6,000 victims of the violence and 500 former guerrillas was intended to strengthen that peace.

The Holy See has also been involved in the negotiations between protesters and the government in Nicaragua and in Venezuela.

But on the American continent, the Pope’s most spectacular diplomatic action remains his mediation between Cuba and the United States. In fact, the growing proportion of Latin American Catholics in the US population makes the Holy See a mediator for the entire continent.

In December 2021 it was announced that Pope Francis may pay a visit to Ukraine in the very near future. The head of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church, His Beatitude Sviatoslav Shevchuk announced that he had spoken to the Pope who had shown concern about the fate of ordinary people, especially those who may not be fully heard today.

He added, “His Holiness was very interested in how the Ukrainian people live, and he is really deeply concerned about this”.

His Beatitude Sviatoslav also said he had told the Pope about the common feelings among representatives of various Ukrainian churches and religions that the war in eastern Ukraine would end after the Pope visited the country.

The pontiff’s peacemaking spirit is also evident in his efforts to engage in dialogue with the Islamic community. Few popes have worked so hard for dialogue with Muslims.

It must be said that in the context of terrorism, there was an urgent need to renew the dialogue, after it had been put on hold under Pope Benedict XVI.

He had provoked a real uproar in the Muslim world with the address he delivered at the University of Regensburg in Germany in 2006, in which he denounced the violence inherent in Islam because of jihadism.

This speech inflicted serious damage to papal diplomacy and led to violence against Christian minorities and to the demonstrations in which effigies of the Holy Father were burned.

DARING STANCES AND BOLD DECLARATIONS

Papal diplomacy is also characterised by a constant desire to build bridges, to create links with all the actors of world geopolitics and to address social problems.

In addition to the Holy See’s relativist view regarding the place of Europe and even that of the West in its international policies, the other type of ‘globalisation’ advocated by the Vatican does not only entail a rebalancing of forces between West and East.

It is also characterised by an attentiveness to migrants and to those excluded from society, in line with the social doctrine of the Church and that of Saint Francis of Assisi, a model of poverty.

From the beginning of his pontificate, the tone was set as his first trip took him to Lampedusa, where he denounced a “globalisation of indifference”, recalled the failings of European leaders and publicly displayed his support for migrants.

The pope recognises the legitimate fears of Europeans in the face of the migratory wave, but considers that these should not drive political action. Far from a simple exhortation to welcome, Pope Francis also considers that migrants must respect the laws and cultural identities of the countries that welcome them.

In short, the pontiff advocates for a true integration of migrants and not an assimilation, erasing the cultural identity of the immigrant but rather a fusion of cultures, in order to avoid the creation of segregated communities.

This nuanced discourse does not prevent him from being very aggressive on the issue. In January 2018 he explicitly took sides in favour of the migrants’ right to land, for a facilitation of family reunification and against the detention of unaccompanied minors.

On his return trip from the Greek island of Lesbos, he even brought back in the papal plane, several Muslim families to the Vatican, which led to strong criticism from Christians in the East. They did not understand the pope’s gesture, as they felt that they are suffering just as much as Muslims.

More generally, there is a growing chasm between the pope and Catholics. While Francis’ criticism of social inequality and the treatment of migrants appeals to agnostics, Catholics seem more reserved in their acceptance of such comments.

Without going back to the war between conservatives and progressives in the Curia, Francis no longer seems to be in tune with many Catholics, who, politically, are turning to xenophobic populists. Although claiming to be Catholics and advocating the Christian heritage these politicians are the exact opposite of the Holy See’s discourse of openness.

Social openness and criticism of capitalism have outraged traditionalists who accuse the papacy of destabilising Europe and accelerating the end of Western civilisation with its pro-migrant discourse. Its 2015 call for all European parishes to welcome two migrant families each has only reinforced the division. Many observers are of the opinion that Francis’ ‘naively idealistic’ interference in the political arena against populism has accelerated the papacy’s detachment from the historical heart of its power, the West.

Every year in January, some 200 diplomats meet in the Vatican’s apostolic palaces to present their greetings to the pope. The head of the Catholic Church then delivers a long speech. On Monday, 10 January 2022, Pope Francis sent his greetings to the 183 ambassadors accredited to the Holy See.

A landmark ceremony during which the pope presented his vision of the world. The Covid-19 pandemic, the situation in Lebanon, forgotten conflicts, the migration issue, the preservation of the common house and the elements for building a culture of dialogue and brotherhood. These were the main themes addressed by Pope Francis in his long speech, in which he also outlined his priorities at the international level for 2022, advocating for multilateralism.

In the Hall of Blessings of St. Peter’s Basilica, Pope Francis recalled in his preamble that the purpose of diplomacy is to “help put aside disagreements in human coexistence”, before addressing the major issues of the moment.

PROMOTING VACCINATION AGAINST COVID-19

It is a personal as well as a collective responsibility, based on “respect for the health of those close to us. Caring for the health of oneself and others is a moral obligation” insisted the Holy Father who regrets the dissemination of unfounded information or poorly documented facts.

He added, “vaccines are not magical tools for healing, but they are the most reasonable solution for the prevention of disease”. As for the authorities, the pope regretted “the lack of firmness in decisions and clarity in communication which are sources of confusion and mistrust and which undermine social cohesion by feeding new tensions”.

The pontiff reiterated his invitation to States and international organisations to adopt “a policy of disinterested sharing as a key principle for guaranteeing access to diagnostic tools, vaccines and medicines for all”.

LEBANON AT THE CENTRE OF THE POPE’S CONCERNS

The first country mentioned by Pope Francis was Lebanon, to which he renewed his closeness and his prayers, and to which he hoped that “the necessary reforms and the support of the international community” would help it to remain firm in its identity as a model of peaceful coexistence and brotherhood between the different religions present there.

Looking back on his 2021 trips to Iraq, Hungary, Slovakia, Cyprus and Greece, he again spoke at length about the migration issue he touched on in Lesbos.

In this context, he particularly urged the European Union to find its internal cohesion in the management of migration, and to establish “a coherent and comprehensive system for managing immigration and asylum policies, in order to share the responsibility for receiving migrants”.

However, the pope did not forget other sensitive points such as the border between Mexico and the United States.

CRITICISM OF ‘CANCEL CULTURE’

If the great challenges of our time are global, the solutions are increasingly “fragmented,” the Holy Father noted. This is why “it is necessary to rediscover a sense of our common identity as a single human family” and to find the path of multilateralism, despite the crisis it is going through. At issue is the misuse of international organisations.

The pope criticised the practice of ‘cancel culture’, a form of ideological colonisation that leaves no room for freedom of expression, the mass withdrawal of support from public figures or celebrities who have done things that aren’t socially accepted today. It is also a way of expressing disapproval and exerting social pressure

The pope spoke out against this practice, “In the name of protecting diversity, we end up erasing the meaning of any identity, with the risk of silencing the positions that defend a respectful and balanced idea of different sensibilities”. He went on to add,“We are witnessing the elaboration of a single thought forced to deny history, or worse, to rewrite it on the basis of contemporary categories, while any historical situation must be interpreted according to the hermeneutics of the time.”

The Pope reminded the attendees that multilateral diplomacy, “called to be truly inclusive”, must not forget permanent values, in the forefront of which are “the right to life, from conception to natural end, and the right to religious freedom”.

Another field of action for multilateralism is the care of our common home, which suffers from “continuous and indiscriminate exploitation of resources“. No one can exempt himself from making efforts, says the pope, who regretted that the decisions taken at the COP26 in Glasgow are too limited.

FORGOTTEN CONFLICTS

Pope Francis hoped that solutions will be found to the interminable conflicts such as Syria, which he said needs political and constitutional reforms, and the lifting of sanctions that directly affect the daily lives of its people, who are increasingly trapped in poverty.

Yemen was also cited as a forgotten war. The Holy Father reiterated the Holy See’s position on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, namely a two-state solution so that the two peoples can live “in peace and security, without hatred or resentment, but healed by mutual forgiveness”.

Francis then reviewed other situations of conflict or tension: Libya, Sudan, South Sudan, Ethiopia, the Sahel, Ukraine, the Southern Caucasus, and Bosnia-Herzegovina.

FRANCIS RECOGNISES THE SIGNS OF THE TIMES

Francis’ tenure as pope has also been noted by the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer (LGBTQ) community for adopting a much more conciliatory tone towards them than his predecessors. “But he who speaks Christian words without putting them into practice hurts himself and others,” he said in 2013.

So where does Pope Francis stand on LGBTQ issues ?

In a 2020 documentary film entitled ‘Francesco’ by Israeli-American director Evgeny Afineevsky, the pope said he favoured civil unions for homosexual couples so that they can have legal protection. “Homosexuals have the right to be in a family. They are the children of God”, he said. However, he added that the term ‘marriage’ should be reserved only for the union of a man and a woman.

Since his election as pope, Francis had already mentioned several times the notion of civil unions for people of the same sex. According to his biographer Austen Ivereigh, Jorge Bergoglio, the future pope, had also defended the merits of this legal protection when he was still archbishop of Buenos Aires, in the context of a heated debate in 2010 on the legalisation of gay marriage.

In the documentary however, he pleads with unprecedented strength and greater freedom of tone in favour of this type of civil union.

To date, the Catholic Church considers homosexual acts to be ‘moral deviance’, at odds with nature as God created it. Not all commentators are convinced that Francis’ words will begin a real opening of the Church.

“ABORTION IS MURDER”

In September 2021, the pope who was asked to respond to a plan by American archbishops to deprive pro-abortion leaders like President Joe Biden of communion, said in general terms that the Church was not called to take a political position.

“What should the pastor do? To be a pastor, not to condemn”, including “the excommunicated”, said the pontiff, without wishing to comment directly on the debates of an American Church often openly present in political life.

On the plane returning from a four-day trip to Hungary and Slovakia, the pope called for “compassion and tenderness,” condemning such episodes of Church history as the St. Bartholomew’s Day massacre or the hunt for witches and heretics.

“If you get out of the pastoral care of the Church, you become a politician,” he said with disapproval.

At the same time, the pope took care to express once again his abhorrence of abortion, which he compared to “murder”.

Pope Francis has spoken out repeatedly on the issue of abortion, most often within a broader reflection on the defence of the weakest, both the elderly and victims of human trafficking. “This defence of unborn life is intimately linked to the defence of all human rights,” which is “the internal coherence” of the Catholic Church’s message, he said.

Without compromising or suggesting that the Church could one day change its position on this issue, the pope emphasises mercy, which implies that Christians should not remain in a position of condemnation, without which ‘the moral edifice’ of his message risks not only being misunderstood but also ‘collapsing like a house of cards’.

DOGS AND CATS REPLACING CHILDREN

Recently, the pope went on the offensive again; this time he targeted married couples who refused to have children. “Today, we see a form of selfishness. We see that some people don’t want to have a child. Sometimes they have one, and that’s it” he declared during his weekly audience on 5 January 2022.

The pontiff regretted that couples are having fewer and fewer children and prefer to welcome pets instead. “Today, couples do not want to have children. Instead, they have two dogs, two cats. And yes, it’s funny, but it’s the truth: dogs and cats take the place of children.”

To give force to his speech on the ‘demographic winter’, Pope Francis used a singular image. He blamed modern couples for not fully investing in creating a family, preferring to adopt pets.

“This denial of motherhood and fatherhood diminishes us, takes away from our humanity. Thus civilization grows old and the country suffers,” continued Francis, encouraging couples “to take the risk” of having children.

The pope did not limit his speech at urging the population to combat the falling birth rate, but he also made an appeal to political forces. He invited the official institutions to “simplify adoption procedures, so that the dream of all those little ones who need a family and of those spouses who want to give love can come true”. A choice – that of adoption – which, in the eyes of the Holy Father, is “one of the highest forms of love and of fatherhood and motherhood”.

PREFERENCE FOR THE PERIPHERIES AT THE RISK OF ABANDONING THE CENTRES

This theology of peace is coupled with an openness to the peripheries, to the margins of world society. Francis, the pope ‘from the end of the Earth’, never ceases to want to address those who are geographically far from the heart of the Catholic world and those left behind by globalisation, but at the risk of losing the support of the heart of his power base.

Whether it is his interest in distant Christian minorities or in migrants and the poor, the marketing aspect of the ‘Pope of the peripheries’ misses the core target by trying too hard to venture into new markets.

But to use a somewhat crude metaphor, it is precisely the core target that keeps a brand alive. By putting into perspective the space occupied by the West, and even by fighting the populist tendencies that are emerging within it, Pope Francis runs the risk of weakening the historical roots of Christianity, as well as its funding.

It remains to be seen whether the Christian communities in Asia and Africa will prove as promising and receptive as he hopes.

After nine years of a particularly dynamic diplomacy, several observations can be made. Pope Francis has made perfect use of all the potentialities of a unique diplomacy with unique objectives, while taking advantage of its media coverage.

Anxious to strengthen peace and considering dialogue as an indispensable tool to the resolution of conflicts, the pontiff has maintained relations with unsavoury regimes and resumed dialogue with the Muslim world while playing the role of international mediator.

But this relativisation of an increasingly closed West threatens the foundations of the Holy See, a Western European institution ‘par excellence’.

This being the case, no one today would poke fun at the diplomatic power of the Apostolic See as Joseph Stalin allegedly did in 1943. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill suggested to Soviet leader Stalin the possibility of the pope being associated with some of the decisions taken at the recent Tehran Conference. “The pope?” said Stalin thoughtfully. “Ah, the pope ! How many divisions does he have ?”