Special Operations Forces of Georgia © Defence Georgia

Irakli Garibashvili is not a name that rolls off the tongue. It’s not one that sits comfortably alongside those of, for example, Alexander the Great, Genghis Khan, Julius Caesar, or William the Conqueror, for instance. But does that matter? He told the media in 2013 that he had sold his assets in Russia “at market price” and he has tried to place distance between himself and the Kremlin, something that probably helped to propel him into the position of Prime Minister of Georgia. There is concern, though, that he may have been able to do that more easily that most people expected because he strictly observes the rules set by Russia, whose own leader has shown staggering incompetence in his decision-making. Indeed, based on what Vladimir Putin has shown the world of his leadership qualities, he would seem to be unsuited to running a small-town sweet shop. In any case, he would probably poison the sweets because he seems to relish killing people, whether or not there is any obvious reason for it. Perhaps he sees it more as a hobby, or maybe he’s a participant in some sort of bargain killing game: poison two, stab one for free. He might even be amusing if he wasn’t quite so sinister.

So, what do we really know about Irakli Garibashvili? Although he is now a serious and successful politician, he had also been a business executive, who then served as prime minister from 20 November 2013 until he resigned the post in December 2015, without explaining why. He is a member of the Georgian Dream party. In the past, Georgia has had some dubious leaders who were not much liked in the West, such as Eduard Shevardnadze, who had been a member of the Soviet Politburo, having been appointed to that post by Mikhail Gorbachev. He did a good job, however, successfully extracting Soviet troops from Afghanistan, for instance, and fighting successfully against organised crime, which had long been an issue in the Soviet Union. That may have been what lay behind an assassination attempt in 1995. It wasn’t the only problem to face Shevardnadze: there was also a failing economy and allegations of corruption, which eventually led to his resignation.

Which brings us back to Irakli Garibashvili, the man at the centre of this article and a man seen by many as Georgia’s greatest hope for a positive future. That may prove to be wishful thinking. He has not pleased the West and has shown himself to be still very much under Moscow’s influence. He has publicly accused Ukraine’s President Volodymyr Zelenskiy of seeking to interfere in Georgian politics, a charge he strongly denies. Georgia had been seeking to introduce a new law to restrict the activities of “foreign agents”, an idea the Georgian parliament has since scrapped. The proposed law was based very much on one that had existed in Russia under the Soviets, preventing other countries from commenting on the country’s internal affairs, so opposition to the proposal was praised by Ukraine, especially as some of the protestors were waving Ukrainian flags. Garibashvili claimed that Ukraine was trying to drag his country into its war with Russia. His comments drew rapid criticism from Ukraine itself, which accused Garibashvili of repeating Russian propaganda. Ukraine’s Foreign Ministry spokesperson, Oleh Nikolenko was highly critical. “We categorically reject such claims, which have nothing to do with reality,” he said. “The Georgian authorities are looking for an enemy in the wrong place.

Ukraine has been and will remain a friend of the Georgian people.” Indeed, it’s hard to understand Garibashvili’s motives in taking such a strong line over something he has said doesn’t matter, especially since opinion polls in Georgia suggests that most Georgians are strongly pro-Ukraine. Both countries aspire to join the EU one day, but on the present evidence it would appear that Georgia will find that harder. At a meeting of the European Council in 2022, the EU acknowledged that Georgia has carried out a number of challenging reforms and successfully aligned its legislation with the EU acquis in many sectors. It did, however express important concerns over the lack of substantial progress and negative developments in some key areas during the previous year. “The EU encouraged Georgia to redouble its efforts to further consolidate democracy and to reduce the political polarisation, to strengthen the rule of law, the independence, integrity and accountability of the judiciary and the fight against corruption,” said the Council report.

| GIVE US BACK OUR BITS OF COUNTRY

Of course, Russia’s aggressive stance towards its neighbouring states inevitably draws criticism from the West. Six Western nations on the United Nations Security Council have demanded that Russia return territory it took from Georgia on the 15th anniversary of the land grab happening. There was a joint statement to that effect signed by the United States, France, the United Kingdom, Japan, Malta and Albania, which described Russia’s seizure of South Ossetia and the Abkhazia region – which had made up 20% of Georgian territory – as “an aggressive trend”. They all pledged to continue their efforts to ensure Georgia’s independence by getting Russia to return the stolen land and recognising the internationally acknowledged borders. Internal affairs in Georgia have not been wholly peaceful, with secessionist movements starting up in some regions, especially Abkhazia and South Ossetia, although when Abkhazia reinstated its 1925 constitution and declared independence, the international community refused to recognise it. After flirting with an association of other former Soviet states, Georgia later signed an Association Agreement with the European Union and joined the Council of Europe and the World Trade Organisation. It also became a partner in NATO, which can’t have pleased Moscow. Russia, while fighting a pointless war in Ukraine that it began without provocation, is also seeking to absorb Belarus (not difficult, I should think), Georgia and Moldova. Well, we all have ambitions.

However, Georgia continues to get closer to NATO, it seems, even if Garibashvili has his doubts. In 2020, a thorough review was conducted by NATO together with the Georgian foreign affairs, defence and interior ministries, as well as with the Georgian Defence Forces and the Coast Guard. This review led to an upgraded Substantial NATO-Georgia Package, which was endorsed by foreign ministers in December 2020.

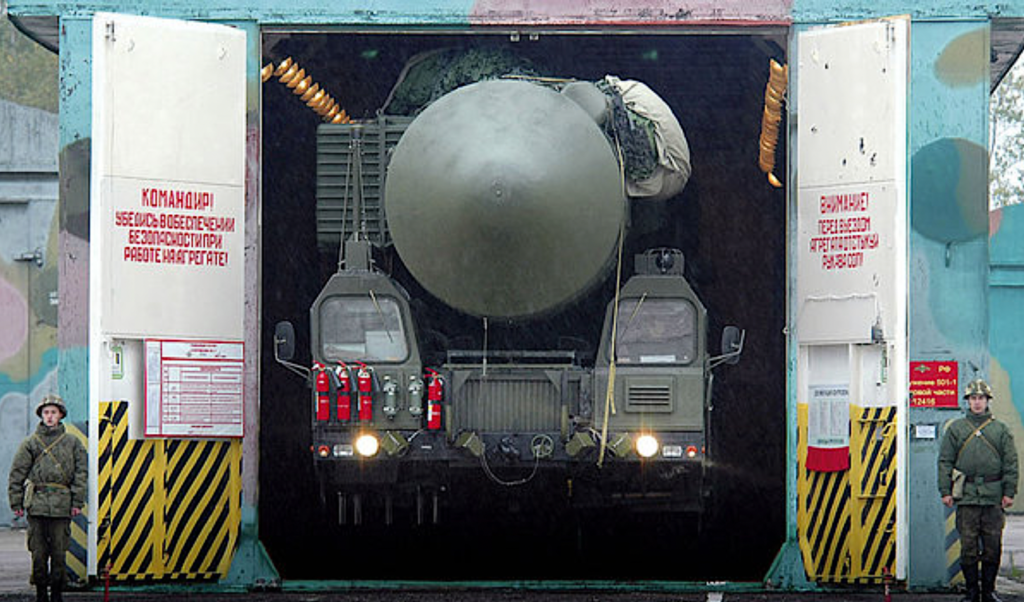

Basically, Putin is the school playground bully. He boasts of having more weapons, bigger, more powerful, in fact of no Earthly use to humankind other than to exterminate large chunks of it. His latest nuclear device is known as the Sarmat, or Satan II, and it has a range of between 10,000 and 20,000 kilometres while carrying up to 15 nuclear warheads to anywhere in the world. A successful test launch in 2022 led Putin to boast that Russia’s enemies would “have to think twice” before issuing threats. But of course, the only country issuing threats is Russia and even Putin isn’t crazy enough to threaten himself. Probably.

We must remember, however, that Belarus, Georgia and Moldova were once part of the Russian hegemony, and Putin wants them back within the fold. The more of the world’s territory he controls (without giving the residents any say in the matter) the happier he seems to be. Putin appears to fear that some of the former Soviet states he has in his sights may decide they would prefer democracy to being told what to do and what to think by Moscow. It’s a great shame: Moscow is a very handsome city that still carries echoes of the glories it once enjoyed. Moscow’s world view bears little resemblance to what we believe in the West. For instance, the demand of six Western countries that Russia should give back (or withdraw its claim upon) parts of Georgia has been dismissed as “hypocrisy”, arguing that Georgia only lost territory because of “a reckless gamble”. We must remember that this is a shooting war we’re talking about, not a board game for children. Russian Deputy UN Ambassador Dmitry Polyansky boasted that relations between Russia and Georgia are improving – a sign of things to come, in his view – with direct flights being resumed between the two countries, despite – as he put it – “the Russophobic West trying to drive a wedge between us at any price.” Really?

Clearly he doesn’t think his country’s eagerness to invade any country that takes its fancy and that appears not to favour a Russian takeover of power is likely to put Russia’s neighbours off seeking closer links.

Georgia’s prime minister has assured other European countries that he still sees his country’s future inside the European Union. “Our country’s path to the EU is irreversible,” he told the media. “In this way, some provocative groups will try to harm our country. Of course, it won’t stop us. We will overcome these provocations and we will achieve our common great goal, which is our country’s membership in the European Union”, Garibashvili said, referencing a few negative comments about Georgia’s European future highlighted on Russian media. Jeffrey Mankoff, a senior research fellow at the US National Defense University’s Institute for National Strategic Studies has recently pointed out how determined Putin is to impose his own imperialist stamp on world affairs. “While Russia’s brutal invasion of Ukraine dominates headlines and diplomatic conversations around the world,” he wrote, “a quieter Kremlin effort to consolidate effective hegemony over neigbouring Belarus, Georgia and Moldova continues apace.” Mankoff explains the thinking behind this unprovoked war where Minsk, Tbilisi and Chișinău are concerned: “Like Ukraine, these three states are former Russian possessions whose post-Soviet independence exacerbated Moscow’s isolation from Europe. President Vladimir Putin and other Russian officials fear that democratic governments in Minsk, Tbilisi and Chișinău (not to mention Kyiv) will be more pro-Western and seek deeper integration both with the European Union and NATO.”

| WHOSE FRIEND ARE YOU?

There are concerns within NATO that Georgia could be Moscow’s next target. Putin has an unusual approach to foreign relations: if he doesn’t like what’s happening on the ground, he sends his troops to change it by force. In a way, NATO has played into his hand by failing to reward Georgia for its support. There is still not a viable time frame for membership or even embarking upon a route towards it. According to Kornely Kakachia, the director of the Georgian Institute of Politics, this has led to what he told DW has turned into “NATO fatigue.” He went on: “Georgia was the first victim of a Russian invasion, one of the front-runners in NATO missions like Iraq and Afghanistan, where it sacrificed its soldiers. Georgia was waiting for NATO to reward that.” It’s still waiting. Meanwhile, Garibashvili told the Global Security Conference in Bratislava that the reasons for Russia’s invasion of Ukraine are plain to see: NATO’s enlargement. “Therefore, we see the consequences,” he said. I’m inclined to think that his view is not fully compatible with Western thinking. Of course, he could be simply hedging his bets. But the comment led to a backlash. “It is hard to imagine NATO embracing a country whose prime minister, echoing Putin’s rhetoric, blames the Alliance for the war in Ukraine,” wrote Nata Koridze, a former diplomat who worked closely with NATO for a Georgian media platform, Civil.ge. One is left to ask the question: how many people have got to die just to satisfy Putin’s vanity?

For Georgia, the whole issue of relations with Russia is difficult. After all, there is a land border between the two countries. They fought a war in 2008 which ended with Russia deciding to recognise the independence of Abkhazia and South Ossetia. Russian troops are still stationed in both. Some believe it’s that border that causes the greatest problem. Another issue is that a country that hosts an extant war in its territory cannot join the alliance. But outside observers have noted how a friendship between Moscow and Tbilisi seems to be deepening, which does not find favour in NATO. At a meeting of NATO’s Military Committee in early 2023, the Committee chair, Admiral Robert Bauer, welcomed Georgia’s representative, Brigadier General Irakli Dzneladze, pointing out that “NATO and Georgia have been Partners for almost 30 years, and over that time we have built a mutually beneficial cooperation that has both enriched and solidified our partnership”. Does that still count for much in today’s convoluted international politics scene? Only time will tell, and it may depend on just how nifty NATO’s footwork proves to be. The problem is that NATO tends to dance in delicate steps while Putin’s Russia marches in wearing military boots and shoots those it doesn’t like the look of. Brigadier General Dzneladze gave assurances of Georgia’s commitment, which were welcomed by Admiral Bauer, who noted that “Georgia has been a long-time and steadfast partner as well as a reliable force contributor to various NATO operations.” NATO heads of state and government representatives agreed at NATO’s Madrid summit to: “step up political and practical support for these specific partners, including Bosnia and Herzegovina, Georgia and the Republic of Moldova.”

As for Russia? Well, Moscow will not smile upon a further expansion of NATO, which is the excuse it uses for invading Ukraine. Georgia, however, has some work to do to prepare itself for NATO membership, if it seriously still wants it. Russia, meanwhile, is demanding assurances from NATO and Washington that neither Ukraine nor Georgia will be allowed to join the Alliance. But Javier Colomina, NATO’s special representative for the South Caucasus, has made it clear to Moscow that NATO’s “Open Door” policy is not up for negotiation. “We’ve been extremely clear with the Russians: We won’t compromise on our basic principles,” Colomina said. “We won’t compromise on the sovereignty and territorial integrity of Ukraine or Georgia. I think it’s 100 percent clear from NATO that we won’t compromise on our open-door policy.”

Colomina made clear to Georgia that it should take steps now to prepare for NATO membership, even if that remains some way in the future. It won’t be easy, and that is largely Russia’s fault. The reason Moscow keeps troops in the separatist regions of Abkhazia and South Ossetia is to prevent Georgia from being admitted to the Alliance: no country can join if wars are going on in its territory. So-called “frozen conflicts” suit Moscow’s purposes very well, and clearly Putin doesn’t care how many Georgians are killed in the process.

Georgia has a number of violent far-right groups that certainly don’t help it towards its stated goal of EU membership. A Gay Pride march was cancelled after violent attacks on journalists following comments by Prime Minister Garibashvili claiming that 95% of the population are opposed to gay rights and that only the military have the right to stage a march at all. Within 24 hours, a cameraman covering the violence had been killed by a far-right mob. Garibashvili may claim his country’s path towards the EU is “irreversible” but his illiberal words don’t suggest that he believes it himself. It may be no more than a sign of how far-right thinking is moving back into the political mainstream, now that so few people are left who remember where it led the last time. Germany’s far-right party, which seems to have growing support, wants the country to abandon the euro in favour of the Deutschmark and also to quit the EU altogether. If the growth of such beliefs is what Garibashvili is counting on, it bodes ill for Europe’s future.

The future for Georgia is very hard to predict. It seems to lean politically in two very different directions, one of them quite favourable towards Russia and its murderous leader. Of course, NATO needs Georgia to keep the peace in the region, but with two frozen conflicts on its territory it’s hard to see things turning out to NATO’s liking. There is disagreement over joining the EU, too, despite what Garibashvili has said. Georgia’s president, Salome Zourabichvili visited Berlin and Brussels for private talks with EU leaders and the Georgian government is now trying to impeach her for it, saying she had “flagrantly violated” the constitution. For a country supposedly keen to join, it’s an odd approach. She has claimed that the ruling Georgian Dream political party is pro-Russian and insufficiently committed to joining either the EU or NATO, which frequent opinion polls have shown to be what most Georgians want.

Former Georgian Defence Minister Davit Kezerashvili accused the Georgian government of being both high-handed and out of touch with what the Georgian people want. “Opinion polls have consistently shown that ordinary Georgians overwhelmingly favour EU and NATO membership.,” he said. “Sadly, the authoritarian actions of the current Tbilisi government are derailing those ambitions, and Georgia appears to be slowly drifting back into the Kremlin’s grip.”

After meeting Zourabichvili, Charles Michel, President of the EU Council, reaffirmed the EU’s determination to assist Georgia in its bid to become a full candidate for EU membership. Thomas de Waal, a senior fellow at the think-tank Carnegie Europe, described what he called the “slide away from democracy” as “alarming” and said it was complicating the country’s efforts to join Moldova and Ukraine as EU accession candidates. After meeting with Zourabichvili in Brussels, Michel reaffirmed the EU’s commitment to supporting Georgia in advancing to candidacy status, and he repeated earlier EU observations that the country needed to pursue reforms in “justice, deoligarchisation (an interesting new word to me) and anti-corruption and media pluralism”.

De Waal noted that the government had banned the entry of high-level critics of Russia to Georgia, which sounds like a restriction on freedom of speech, while the prime minister, Irakli Garibashvili, had accused those who urge more support for Ukraine of being a “party of war”, although it’s Russia’s tanks that are rolling across Ukraine and Russian missiles and drones that are destroying homes, schools and hospitals. Despite the actions of far-right extremists, research suggests (as I’ve said) that most Georgians favour a future that is European in flavour and in freedoms, but the Georgian government seems to have a contrary approach. In terms of the propaganda war, in Georgia’s case Russia would seem to be winning.

The illiberal side of any debate on human rights would also seem to be leading the field. Kicking off a sitting of government, Irakli Garibashvili said it is “the opinion of our population” that Gay Pride marches should not be allowed to go ahead in Georgia,” he said, before entering into a bizarre debate on semantics. “I know only one parade – the parade of our army, which will be held in our country,” he said, although he has welcomed marches in support of his political party. “When 95 per cent of our population demonstratively opposes the propagandistic parade, we must all obey it,” he continued, albeit without any sort of plebiscite or sign that most people share his views.

With no proof whatever, he continued: “This is the opinion of our people and we as a government elected by the people must obey it. Police arrested the perpetuators. We will hold all the perpetrators accountable.” It’s hard to believe that he really wants to see Georgia as a member of NATO or the EU. His rhetoric seems geared more towards keeping Moscow happy.

There are, of course, many different views where Gay Pride is concerned, but it seems hard to see street violence as a matter of policy. Garibashvili’s certainty that a large majority want to see it stamped out is without any proof whatever. It may well be (and almost certainly is) that most people are not homosexual and would not indulge in its practices, but that’s a long way short of supporting thuggish violence against those who are that way inclined. For most people, I think, a person’s sexual orientation is of very little concern, if any, and unlikely to affect how they work. It’s easy to see why NATO and the EU support Georgia for wanting to join them in policy terms: the more the merrier, as they say. Whether or not Georgia will live up to its promise is another matter entirely, the outcome far less certain in the longer term.