The year is 2017, and the place, the small town of Amer in the Province of Girona, some 120 kilometres north east of Barcelona. Far from the hustle and bustle of politics, Carles Puigdemont, the second of eight children was supposed to take over the family bakery and cake shop when he grew up. But he decided otherwise.

His father still lives there. Even though he is over 80, he still comes every day to check everything is going well at the shop, which is now run by one of his daughters.But the family is going through some difficult times because not everyone likes Puigdemont’s independence bid; it has its opponents in the village and the region at large.

In June of that year, Puigdemont had announced that the independence referendum which he had promised the Catalans in his election campaign would be held the following October.This was the straw that broke the camel’s back. Spain’s Constitutional Court blocked the referendum by suspending the Catalan legislation and immediately put into effect a vast police operation to disrupt the voting process and to arrest the politicians behind the move.

Despite this and the boycott organised by opponents of secession, the referendum went ahead. Turnout was only 43% but among those who voted, over 90% were in favour of independence.Carles Puigdemont had indeed kept his word.

The formative years and beyond

It was in that same town of Amer that Carles Puigdemont was born on 29 November, 1962.

He completed his elementary education there, before being sent to a boarding school in Girona, where Spanish was used as the official language.

Some of his old schoolmates became life-long friends; one of them is Salvador Clara Pons who became deputy-mayor of Amer. He is now a member of the leftist Catalan Republican Party. His small office in the Town Hall is decorated with a Catalan flag and on the wall behind his desk, hangs a framed portrait of Carles Puigdemont.

There are no visible signs of anything related to the Spanish monarch, King Felipe VI.

During a brief interview in 2017, given to French news channel, ‘France 24’, Clara Pons quipped :

“The King ?…no, not here ! This is the independent Catalan Republic…that’s what the people wanted ”.

Clara Pons and Puigdemont have the same age; they spent practically all their summer holidays together. The deputy-mayor still remembers the emotion they felt following the attempted coup d’état in Spain, in February 1981.

“I remember Carles coming over to our house at around 5:30 in the morning to inform me that there had been a coup d’état. We switched on the radio and then we both went out. He wanted to plant a Catalan flag on top of the mountain…as an act of resistance !”

After that event, the two friends stayed in touch constantly. “I think the year was 1985, and by then, we were grown-ups. Carles was already working as a journalist and we would both attend meetings and demonstrations where we demanded that all the street names and sign posts in our village to be spelt out the way we pronounced them…in Catalan”.

At the school that Puigdemont attended in Amer, his former history teacher, Mercè Vila Coll has kept the copies of the school news sheet where the young Puigdemont first tested out his political ideas, and she recalls his keen awareness of political realities.

“He disliked the way history was taught in school textbooks, especially the history of Spain. He believed it was a very limited vision of Catalonia’s history. He said something else too; he couldn’t understand why there were still books in Castilian Spanish”.

However, Mercè Vila Coll is not at all surprised by the career path of her former pupil.

“Stubborn…he’d always been stubborn ! He’d always known what he wanted in life and in the end, he was offered the ideal position that would allow him to make Catalonia what he always wanted it to be…that is to say, an independent country”.

During his teenage years, Puigdemont showed a very keen interest in politics; he was already a reporter for a local newspaper in which he wrote articles on football, and other news.

But he also regularly attended political meetings andjoined the Crida Nacional per la República or National Call for the Republic, a pro-independence movement created to defend Catalan culture. He continued taking part in marches and demonstrations with members of the Young Catalan Nationalists.

In 1980, at the age of 18, he joined a conservative Catalan nationalist party, the Democratic Convergence of Catalonia, which later changed its name to today’s Catalan European Democratic Party (PDeCAT).

His strong interest in politics and in the written medium followed him all the way to the University College of Girona, where he enrolled on a course to study Catalan philology.

In 1983, the 21 year-old Puigdemont experienced an event that changed the course of his professional life : he was involved in a serious car accident that badly injured him and left a scar on his forehead.

Although his friends deny it, it is widely believed that he adopted his characteristic Beatle-style haircut in order to hide the scar.

Be that as it may, he eventually decided to drop out of university and to embark on a career in political journalism.

Journalism leading to politics

His first stint in the profession was at El Punt Avui, a pro-independence Catalan newspaper. Here, he began as journalist and gradually rose up the ranks to become sub-editor and then the paper’s editor-in-chief.

Later in his career, he became director of the Catalan News Agency (ACN) which he had founded, as well as Catalonia Today, a weekly publication in English whose editor is none other than Puigdemont’s Romanian wife, Marcela Topor whom he had married in 2000.

Topor who is a professional journalist also hosts television shows that are broadcast on the El Punt Avui channel and are posted on the Catalonia Today website.

These programmes feature mainly interviews in English with foreign residents in Catalonia.

Puigdemont remained at the helm of ACN until 2002, when he was offered the position of director general of the Girona Cultural Centre; he held this position until 2004.

He left journalism for politics in 2006 when he was invited to be a candidate for the Catalan Parliament by the Convergence and Union Party (CiU), a Catalan, nationalist alliance.

In 2007, Puigdemont ran for the local elections in Girona as CiU’s candidate, but although he was elected, his party remained in opposition.

However, in 2011 he was elected Mayor of Girona after winning the municipal elections, in which the CiU managed to put an end to 32 years of rule by the Socialist Party in that city.

And four years later, in July 2015, he became the new president of the Association of Municipalities for Independence, an organisation of city councils created with the aim of achieving the independence of Catalonia.

The next stage in Puigdemont’s meteoric political rise unfolded in September 2015 when he was elected as an MP for Girona’s ‘Junts pel Si’ (Together for Yes) candidature in the elections for the Parliament of Catalonia.

‘Junts pel Si’ (JxSi) was a Catalan parliamentary group and political alliance dedicated to achieving the independence of Catalonia.

Catalonia is a wealthy, semi-autonomous region in northeastern Spain with a distinct history that dates back to almost 1000 years. It consists of four provinces and its population is around 7.5 million. Catalonia has its own flag, anthem, parliament and language.

It also has its own police force and a number of public services are under the direct control of its government.

Heading for confrontation

January 10, 2016 was a memorable date in Puigdemont’s career; it was on this day that he was elected 130th President of the Government of Catalonia.

His predecessor Artur Mas had failed to secure enough support in Parliament in the 2015 general election and was forced to resign.

It was following a last-minute agreement reached between pro-independence parties Junts pel Si and Popular Unity Candidacy (CUP) that Carles Puigdemont was elected.

He promptly resigned as Mayor of Girona the day following his election and remaining true to his beliefs, he did not to take the official oath of allegiance to the Spanish constitution and monarch; instead he vowed loyalty to the people of Catalonia.

The head of the Catalan Parliament who presided the swearing in ceremony had in fact read :

“Do you promise to faithfully fulfill the obligations of the position of President of the Catalan Government faithfully, to the will of the people of Catalonia, represented by their parliament?”

Puigdemont had no qualms whatsoever when, in front of the official delegates of the central government in Madrid, declared :

“We are humiliated financially, neglected by state institutions, disregarded in the recognition of our identity and our language”.

Later in his speech, stressing that he had promised to be loyal to the Catalan people, he made a reference to the same idea :

“We cannot do this in any which way. I will not allow it. We will do it very well. I promise to work to calm down the atmosphere and explain; we need to tell more people and involve more people”.

The negative effects that these declarations produced in the Spanish Establishment didn’t take long to manifest themselves.

Traditionally, the Presidents of the Catalan, Basque, Balearic and Galician Parliaments – the four autonomous regions of Spain – personally travel to Madrid to inform the King of their respective governments’ decisions in these matters.

When the President of the Catalan Government, Carme Forcadell asked for an official audience with King Felipe VI, the Royal Household refused her request. She was asked to communicate the investiture of the new Catalan President in writing.

She duly complied, and Parliament later confirmed that the official communication had been made by email.

The path to constitutional crisis

Carles Puigdemont has always been a die-hard separatist, and he promised his electorate nothing less during the campaign that saw him become President of Catalonia in 2016.

However, his political party at the time, the Catalan European Democratic Party was not primarily and necessarily focused on independence from Spain.

Its members are mainly from middle-class, conservative and nationalist segments of Catalan society.

It had entered into negotiations and had even formed alliances with established political parties in Madrid in order to advance the cause of Catalan independence through gradual measures and steps that would grant more autonomy to the region.

But among its leaders, it was Puigdemont who was something of a firebrand and a maverick who demanded that Catalonia become independent immediately, come what may.

However, as well as being a deft politician, he was also a man of compromise. After all, the coalition that he headed in the Catalan Parliament seemed stitched together and lumpy; on one side was the extreme left and on the other, the conservative elements of the right. And in between, were the moderate parties from the left, as well as other nationalists.

At first sight, it did not appear that these parties could reach a consensus. But they did… once. They joined forces for the regional election in Catalonia in 2015 and emerged as a pro-independence coalition, with an absolute majority of seats in the regional parliament.

In June 2017, Puigdemont announced that the referendum on Catalan independence would be held on Sunday, 1 October.

The Catalan Parliament duly passed legislation authorising the referendum which would not only be binding but would also be based on a simple majority without a minimum threshold.

The Spanish government promptly warned the Catalan Parliament that the planned referendum was illegal under the constitution, but to no avail.

And so, ahead of the vote, Spanish police seized control of ballots and fliers, raided the Catalan regional government’s offices and shut down pro-independence websites.

On voting day, there were scenes of violence that resulted in an estimated 800 people being injured when police stormed polling stations and tried to prevent people from voting by firing tear gas into crowds of prospective voters.

Late on Sunday night, 1 October, the Catalan regional government confirmed that although turnout was only 43%, as many opposed to secession boycotted the poll, over 90% of those who voted chose independence. And then, it announced that it planned to unilaterally declare independence from Spain within 48 hours.

Madrid immediately replied that it would neither recognise the results of the referendum nor a declaration of independence.

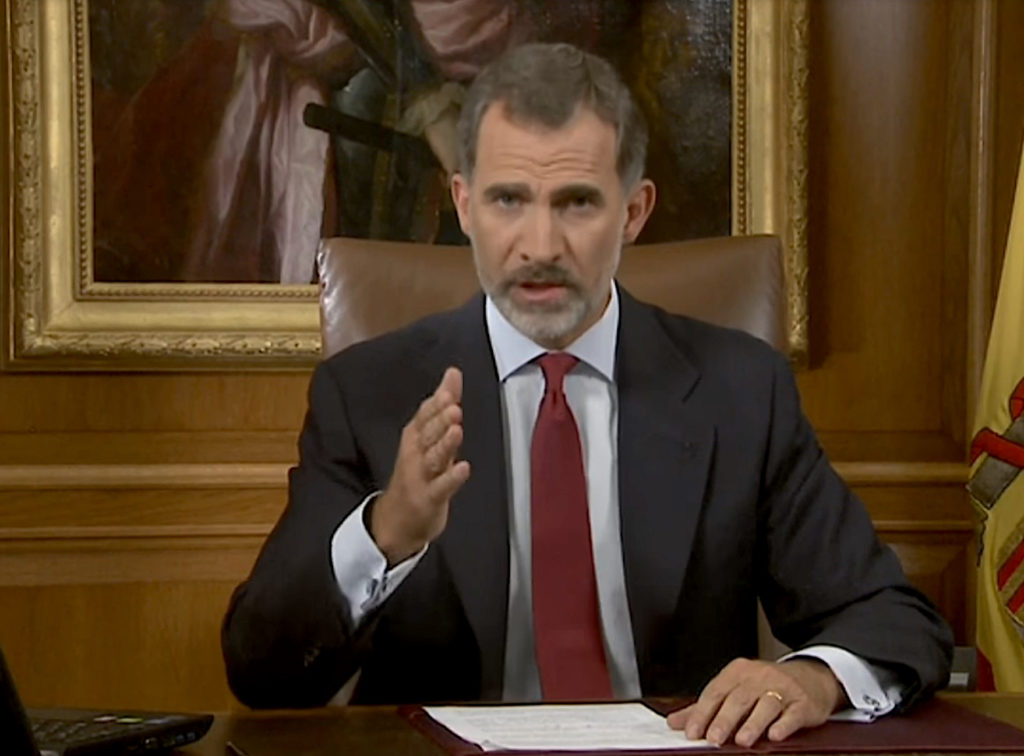

King Felipe VI accused Catalan leaders of jeopardizing the stability of the country and urged the Spanish government to defend constitutional order.

The tumultuous referendum sparked an escalating conflict that was described as the biggest political and constitutional crisis in Spain since the end of the Franco dictatorship in the mid 1970’s.

Catalan leaders claimed victory but the Spanish government remained in denial.

Carles Puigdemont was in a defiant mood when he addressed his supporters after voting was declared closed :

“We have won the right to be listened to, to be respected and to be recognised. Today, millions of people mobilised, facing all kinds of difficulties and threats. You have said loud and clear that you have a message for the world. We have the right to decide our future, we have the right to be free and we want to live in peace and apart from a state that is incapable of promoting one single thing rather than imposition and the use of brute force”.

In a television address, Spanish Prime Minister, Mariano Rajoy in turn expressed scathing criticism of the Catalan authorities and all other instigators of the crisis :

“ We saw behaviour and attitudes that would disgust any democrat and that should never be repeated. Indoctrination of children, harassment of judges and journalists, without going any further. I would like to clearly say that the people responsible for these acts are only and exclusively those who have promoted the violation of the law and the rupture of social harmony”.

Thousands of protesters gathered in Barcelona the day after the violence and the mayhem that ensued. The Catalan government went into a huddle before joining protesters on the streets as the Spanish Prime minister met with his party colleagues in Madrid.

The big question at that moment in time was : What happens next ?

Options were somewhat limited for Mariano Rajoy. He could have moved to invoke Article 155 of the Spanish constitution which would have allowed Madrid to take control of Catalonia.

Carles Puigdemont on the other hand said that Catalonia would make a unilateral declaration of independence after it secured over 90% of the vote in favour of breaking away.

Ties between Catalonia’s government and the centre were at an all-time low and the option to invoke Article 155 could have sparked a fresh wave of unrest.

Both leaders refused to blink and the likelihood of talks to resolve the dispute remained slim.

Testing Madrid’s resolve to the limit

Ten days after the referendum, Carles Puigdemont made a move that sparked confusion in Barcelona as well as in Madrid.

Together with his separatist allies, he signed a declaration of independence but to the dismay of many of his supporters, he suspended its implementation to allegedly give Madrid time for negotiations.

Entering into negotiations with Spain’s autonomous regions regarding revisions in their status is something that Madrid has always avoided in order not to set a precedent.

However, Prime Minister Rajoy duly acknowledged Puigdemont’s request and gave the Catalan Parliament six days to clarify its position.

Puigdemont however refused to either confirm or deny the declaration and called for negotiations instead.

This was seen by many observers as a clever move; it put Madrid in an embarrassing situation in that it was obliged to acknowledge Catalonia’s request, and what’s more, was not in a position to implement Article 155, as long as long as Catalan intentions were not unequivocally stated.

Madrid again agreed to give Puigdemont and his allies an extended deadline to state clearly whether they intended to secede. But no definitive answer was forthcoming; calls for dialogue and negotiations had clearly failed.

With two pro-independence leaders in prison for sedition and the threat to suspend Catalonia’s self-government on the table, President Carles Puigdemont left it up to Parliament to decide what would happen next…and it did.

After dramatic hours of negotiations between political parties and the government, a historic, plenary session of the Catalan Parliament started on 27 October 2017, with huge expectations.

Out of the 135-member Parliament, 70 voted in favour of independence, 10 MPs voted against and 2 abstained. Unionist MPs had left the Chamber in protest.

What followed was joy by the majority of MPs. They were fully aware of what they had just voted on because the President of the Chamber, Carme Forcadell had read the whole declaration before the vote :

“We hereby constitute the Catalan Republic as an independent, sovereign, legal, democratic and socially-conscious state”.

Immediately after the historic declaration, the atmosphere in Parliament became pretty intense. Hundreds of mayors were in the building to express their support for independence while large crowds waited outside.

MPs and members of the government were cheered by their supporters as they left the plenary. However, they all had one eye on Madrid, awaiting the Spanish government’s reaction.

Meanwhile city councils and official buildings began removing the Spanish flag, a state they no longer considered themselves part of.

Catalonia found itself in unchartered and potentially dangerous waters; while there were celebrations, there was also nervous anticipation…a knowledge that not every Catalan wants this rupture as well as fear about the immediate future.

Those fears proved justified. The Spanish government held an emergency cabinet meeting to respond to the declaration of independence. The Spanish senate green lighted the suspension of Catalonia’s autonomy and Article 155 of the constitution was activated, allowing the dismissal of the full Catalan government and granting Madrid powers to impose direct rule on Catalonia.

Prime Minister Rajoy’s statement was carried by Spanish television as well as world broadcasters :

“I dismiss the Catalan President, the Vice President as well as the rest of the ministers of the regional government. Catalan delegations abroad, and the so-called embassies, except the one in Brussels will be closed down. I dismiss the delegates of the Catalan government in Brussels and Madrid. I inform you that I have dissolved the Catalan Parliament and that snap elections will be held on 21 December 2017”.

The prosecution also presented lawsuits against Catalan leaders for rebellion, sedition and misuse of public funds; charges that carry sentences of 30, 15 and 6 years in prison respectively.

Exile and shattered dreams

Shortly after charges were laid by the Spanish Attorney General, Puigdemont fled Barcelona. Together with five of his colleagues, he was driven to Marseille (France), where they boarded a flight to Brussels on 30 October 2017.

He claimed that in the ‘capital of Europe’, he could seek legal protection and could speak freely. He also declared he would not be returning to Spain unless he was guaranteed a fair trial.

It is probably no coincidence that earlier, the then Belgian minister for Asylum and Migration, Theo Francken who is himself a die-hard nationalist and an advocate of Flemish independence, was quoted as saying that the prospect of Puigdemont being granted asylum was “not unrealistic”.

Also, Belgium and Spain had already been at loggerheads in the past over the extradition of members of the ETA, the Basque separatist organisation.

The Belgian lawyer who Puigdemont consulted, after Spain issued a European Arrest Warrant against him, was none other than Paul Bekaert.

In 2013, in a high-profile case, he had succeeded in blocking the extradition of Natividad Jáuregui, a member of the ETA, on the grounds that her fundamental rights could have been violated in Spain.

Meanwhile, Carles Puigdemont prepared to settle into a new home for a possibly long stay in Belgium. A large, six-bedroom, €4.400 per month villa was rented on his behalf by a close friend and advisor in the upmarket suburban town of Waterloo, just outside Brussels.

Since fleeing Spain, the former Catalan President had been able to travel relatively freely, thanks to Europe’s lack of internal borders.

But shortly after crossing the border from Denmark into Germany on a trip back from Finland in March 2018, he was identified by motorway police and detained.

It later emerged that the Spanish secret service had followed Puigdemont’s car from Finland to Germany, where they alerted police and urged them to arrest him following the reactivation of the European Arrest Warrant issued by the Spanish Supreme Court on the charge of rebellion.

A German judge decided to keep Puigdemont behind bars while the arduous judicial process

to decide his extradition was in progress.

Mr Puigdemont’s Spanish

lawyer© Wikicommons

His detention made headlines around the world and sparked tense protests in Catalonia. Puigdemont’s many critics have branded him a coward and a scoundrel who gambled and lost with an illegal and unconstitutional referendum.

But his supporters insist he is a democrat and a political hero, suffering for the cause of freedom.

This is an image he himself has cultivated throughout his exile. In Finland, where he had travelled for talks with local MPs he declared :

“I will continue my struggle in order to defend my rights as a citizen, as a member of the Catalan Parliament, as a President and to defend the rights of the people of Catalonia”.

In July 2018, the High Court in the German state of Schleswig-Holstein where Puigdemont had been detained decided that he could not be extradited for the crime of rebellion but that the charge of misuse of public funds levelled against him might still trigger the process.

But in the end, the extradition attempt came to an end when Spain dropped its arrest warrant.

Puigdemont was again free to travel and decided to return to Brussels.

In May 2019, despite an attempt by the Popular Party and Citizen’s Party in Spain to prevent Puigdemont running in the European Elections, by asking the central electoral committee to ban him, a Spanish court ruled that his political rights remained intact.

He was selected by his pro-independence party, Junts per Catalunya (Together for Catalonia) and was elected member of the European Parliament.

However, he was not able to officially take up the position. Although his lawyers were convinced that he should have been able to, the legal services of the European Parliament confirmed he must personally go to Madrid and swear to the Spanish Constitution, before the central electoral board.

But if he did so, he risked being arrested, as he would have had no political immunity yet.

Puigdemont next sent a request to the General Court of the European Union for precautionary measures against the European Parliament’s decision. But his request was dismissed outright.

And to make matters even worse, in October 2019, the Spanish Supreme Court reactivated an international detention order for Puigdemont.

Even though he was officially accredited as an MEP in December 2019 following a ruling from the European Court of Justice, Puigdemont now seems to have suffered an unmistakable defeat on the political battlefield.

There is a glimmer of hope though for the Catalan pro-independence movement, following the November 2019 general election in Spain. The Socialist Party (PSOE), headed by Pedro Sanchez won the most seats but fell short of a majority in parliament.

However, Catalonia’s largest separatist party, the Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya (The Republican Left of Catalonia or ERC ) has declared its willingness to enter into a coalition, along with other leftist and Basque parties to allow Pedro Sanchez to continue as Prime Minister.

The hope is that, as promised by the Socialist Party, negotiations between Madrid and Barcelona will unblock the political conflict over the future of Catalonia and pave the way for its resolution.

Carles Puigdemont on the other hand, faces a very uncertain future.

If he returns to Spain, he will possibly be charged with sedition, rebellion and misuse of public funds, and if he remains in Belgium, he ultimately risks political irrelevance and may gradually fade into oblivion.

Hossein Sadre

Click here to read 2020 February’s edition of Europe Diplomatic Magazine