Eurofighter typhoon fgr.mk 4 © SAC Cathy Sharples

In May 1993, when the Maastricht Treaty was put to the Danish people for a second time, British Europhobes got involved in campaigning for its rejection. Again. Indeed, it did seem somewhat indelicate, even for the supporters of the European Union, to be holding a second referendum on the same Treaty less than a year after it had been narrowly defeated, albeit by a tiny 50.7% – 49.3% margin. There had been some tinkering with the wording in the interim but most saw that as purely cosmetic. The rejection in June, 1992, so soon after the creation of the Single Market, was a major blow to European integration and took EU officials and other Europhiles by surprise. It might, with the benefit of hindsight, have been wiser to take a little longer, make more meaningful alterations and sell it more coaxingly before letting the Danes have another shot at it. But it was done in a rush and it succeeded.

In order to cover the event, I travelled across Denmark with a camera crew by road from Esbjerg on the west coast of the Jutland peninsula, making reports along the way, before arriving in the Danish capital. We had a few adventures, too, before arriving, like our encounter with the chainsaw-wielding pig farmer that forced us (two males, one female) to share a bedroom whose door panel had been kicked in, but that’s a story for another time.

member of parliament

© Wikipedia

In Copenhagen there was a great deal of campaigning going on and a number of people drafted in to address crowds. I and my crew went to film one of the more bizarre: a punk event staged by a black-clad anarchist theatrical group which included impenetrably abstruse street theatre aimed at a young audience gathered around the podium and seated on the ground. One of the speakers was a leading British Eurosceptic member of parliament, Bill Cash (Sir William Cash since 2014), complete with tie, suit and smart shirt. He looked as out of place as a boiler suit at a society wedding or a dinner jacket down a coal mine, but when called upon he duly began to speak in strident criticism of the Maastricht Treaty and European integration in general. However, his words on such things as trade and immigration cut little ice with the youngsters sitting around, some of whom started to seem bored and restless. They couldn’t imagine why they should listen to a middle-class Englishman in a suit addressing them in English. Until, that is, he told them in a flash of inspiration that if Denmark approved the Treaty they’d all be called up to serve in a European Army. That worked, although it was, of course, utter tosh. There was not then, is not now nor is there ever likely to be a real European Army and conscription is unlikely to reappear anywhere in Europe unless there’s a war.

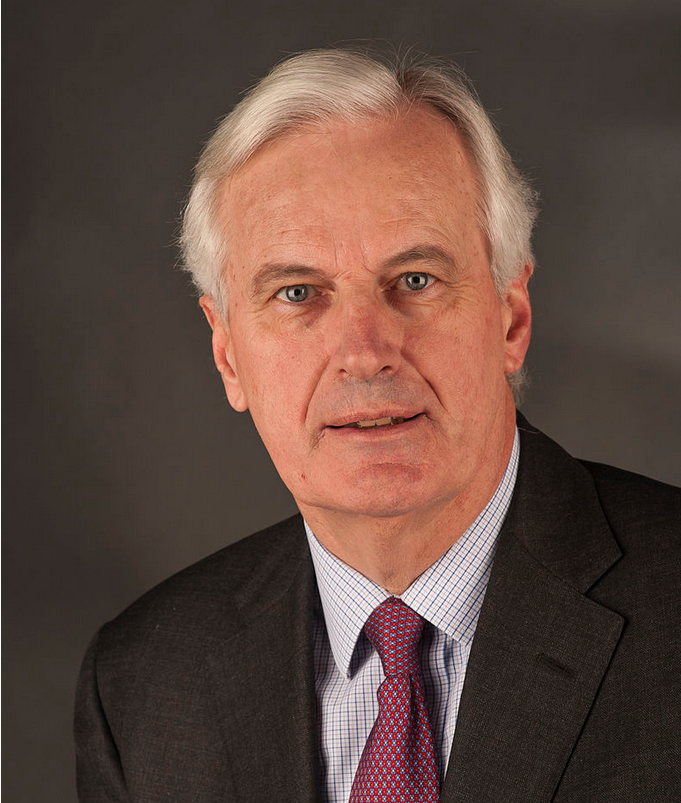

President of the European

Commission

© Bundesregierung/Kugler

Sir William, though, was never one to let facts get in the way of a sound argument (or even an unsound one). I was once seated near him at a formal dinner in London’s Carlton Club, that bastion of British Conservatism that boasts huge portraits of Margaret Thatcher, Winston Churchill and other Tory notables and which even has Benjamin Disraeli’s cabinet table in one of its downstairs rooms. The room (and table) can be hired by members; their dinner guests can now eat where Sir Stafford Northcote, as Chancellor of the Exchequer, once argued budgetary policy, while Richard Assheton Cross, 1st Viscount Cross, served as Home Secretary, should such an idea appeal. But I digress; the point is that the dinner table where I was sitting emptied of Tory worthies hurrying off the moment the food was over, leaving me, very much an outsider, stranded with Cash. His colleagues tended to desert him on these occasions because of his obsessive tendency to talk about his dislike of the European project. In fairness, however, I should mention that in Copenhagen he was the very picture of patience when we were stranded together outside the press centre for a live late-night TV interview which was cancelled without anyone telling us. We even managed to talk about other things during our half-hour wait, although I do not remember what.

WHERE’S THE WAR?

So, no European Army, whatever Sir William may think, at least for now. The new President of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, however, has spoken of her wish to see a European Defence Union within the next five years, despite her continuing support for NATO as the “cornerstone of Europe’s collective defence”. France’s President Macron, too, has urged his fellow European leaders to get behind a plan for the EU to develop a military force of its own; he argues that the EU should start to see itself as a political force, not just a market. Indeed, Article 42 of the Treaty on European Union (the Maastricht Treaty) sets out a commitment towards “the eventual framing of a common defence policy, which might in time lead to a common defence when the European Council, acting unanimously, so decides.”

Oberpfaffhofen, Germany

© GSA, ©European GNSS Agency

Is there any place in there for the participation of a non-EU United Kingdom? As EU Brexit negotiator Michel Barnier told the annual conference of the European Defence Agency last November: “Brexit means Brexit – also when it comes to security and defence. Once the United Kingdom has left the Union, it will be a third country,” he warned, “It wants and will pursue a foreign policy based on its own national interests.” Barnier’s message on Britain’s imminent departure from the Union was bleak and full of regret, but it was not without some vestige of hope: “The United Kingdom leaves the Union. It does not leave Europe. We are bound by values, history and geography. We will continue to face major common challenges. In the face of threats to our shared security, we must continue to show unity and strategic solidarity. As European leaders did after the attack in Salisbury in 2018.” A nifty reminder there to Britain’s Eurosceptic government of how their EU neighbours supported them at a time of crisis and threat. We all need friends.

Although the European Union lacks a standing military force, there are a number of EU-led military operations, which have to achieve unanimous agreement by member states before being put into operation. Former and current examples include European Force Althea, implementing the Dayton Agreement in Bosnia Herzegovina, European Union Naval Force Atalanta, aimed at combatting piracy off the Horn of Africa, and Operation Sophia, which identifies and disposes of vessels used for people trafficking in the Mediterranean. Britain has voluntarily given up command of the Atalanta operation in the light of its imminent departure from the EU.

According to a House of Commons Briefing Paper, “The UK currently contributes to seven out of 16 EU-led military operations. These operations involve approximately 200 British personnel and several military assets. The UK’s principal contribution to EU-led operations has been at the strategic command level.” Britain’s contribution to the European Defence Agency has been minimal, however, with successive British governments regarding NATO as the principle bulwark against foreign adventurism. France and Germany have long favoured creating an EU military presence but the notion has always been opposed by the UK. Brexit may help the idea to come to fruition. But leaving the EU will make an inevitable difference to Britain, according to the Briefing Paper: “At the strategic level, following Brexit, the UK would no longer be involved in decision-making mechanisms for the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) and the Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP). The CFSP and CSDP are used to co-ordinate joint responses to foreign policy challenges across all EU Member States.” It continues: “There are also questions around intelligence sharing among the EU Member States. In the event of a no-deal Brexit there might not be a legal mechanism in place to share classified information between the EU and the UK.” This is potentially more worrying for Britain’s former partners and for a Britain on its own, especially in a more volatile world in which both Russia and China are becoming increasingly assertive. To date, according to the Institute for Government, research by Britain’s House of Lords EU Committee found that the UK has contributed just 2.3% of the personnel supplied by EU member states to CSDP missions.

That may seem a measly share of the burden but the UK remains (while it is still a member) the EU’s strongest defence force. As the Institute for Government explains: “It is one of only two member states possessing ‘full-spectrum’ military capabilities (including a nuclear deterrent), and is one of only six member states meeting the NATO target of spending 2% of gross domestic product on defence. The UK also holds a permanent seat on the UN Security Council and has the largest military budget within the EU.” That may change, however: UK military spending is under review by the new government and cuts to help fund election promises seem inevitable.

WE COME IN PEACE

The European Union has never sought to be a military power; the Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP) was created by Britain and France at the 1998 summit in St. Malo following what was seen as Europe’s failure to address the challenges of the Balkan Wars. It had held a lot of meetings of the various participants, where Serbian president Slobodan Milosevic used to entertain journalists with his impersonations of other participants, especially the then Croatian president Franjo Tudjman, for some reason. The EU’s External Action Service, makes clear its purpose: “Diplomacy, humanitarian aid, development cooperation, climate action, human rights, economic support and trade policy are all part of the EU’s toolbox for global security and peace. These different instruments are combined in a specific way fitting the particular circumstances of each crisis or situation.” It all comes down to what Britain views as the EU’s “soft power”.

Most of the missions the CSDP undertakes involve civilian personnel, not military, and the EU has signed 18 Framework Participation agreements (FPAs) allowing third countries to take part in CSDP operations and missions, including Norway, Canada, Turkey and the United States. None of these, however, has the sort of decision-making rôle that the British government has described as its ‘preferred model’. Participating third countries get involved at later stages of the planning and must accept EU timelines and procedures. However, the EU’s new Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO), set up to develop defence capabilities together and make them available for EU military operations, is being shunned not only by Britain but also by Denmark and Malta. The most Euro-sceptic nations retain their scepticism, it seems, although the UK’s Defence Select Committee was told that the British government wants “to ensure that PESCO projects remain open to third parties, because there may well be some projects that we do want to participate in as a third party”. Presumably that means that the UK will ask to participate; outside the EU it will no longer be able to take part as a matter of course. So far, 34 PESCO projects have been identified, including a medium altitude long-endurance drone, an upgrade to the Tiger attack helicopter and a ‘high-altitude Intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR) capability’. These would remain under the control of individual participating member states but it seems unlikely that after Brexit, especially a no-deal Brexit, Britain will be invited to take part in their development.

A no-deal Brexit – still a distinct possibility – would exclude the UK not only from CSDP decision making (that will happen even with a deal) but from participation in or command responsibility of any CSDP mission or battlegroup. Any UK military or civilian personnel deployed on EU missions would have to return home to Britain, along with all military and civilian staff seconded to the EU. But the EU states also cooperate on non-military security issues, including policing and criminal justice. It is in this field that a question mark hangs over another project in which Britain has played an important rôle: “The EU also cooperates on wider security matters, including policing and criminal justice,” says the Institute for Government. “It is also building a global satellite navigation system, known as Galileo, which provides services to individuals, businesses and public bodies, including on a secure platform used by policing and military authorities.

The UK has contributed funding and expertise to the Galileo systems, and hosts key Galileo infrastructure on its south Atlantic territories.” The issue of whether or not Britain will choose to or even be allowed to participate in the project post-Brexit has yet to be resolved, although in December 2018, the government said it was no longer seeking access to secure aspects of Galileo and that the UK would instead build its own Global Navigation Satellite system. That is like to come at a very steep price and it’s hard to see how such spending could be squared with other ambitious and costly election promises. However, the power to develop and implement security and defence policies lies – as it always has – with individual member states, not the EU. The EU may yet exclude the UK, as a third country, from future projects with a security dimension, which would include Galileo, or the UK could try to go it alone in some way, as it has hinted.

THE INBALANCE OF POWER

In terms of military hardware, the UK supplies a considerable proportion of the necessary equipment. It provides 5% of main battle tanks, 50% of nuclear attack submarines which also have the capability to land special-operations forces and to launch land-attack cruise missiles (France possesses the other 50%), 18% of frigates, 44% of early-warning aircraft, 53% of heavy aerial attack drones, 49% of the heavy transport fixed-wing aircraft and 27% of heavy transport helicopters. The fact is that despite recent and on-going spending cuts, the UK has the largest defence budget in the EU and, according to the International Institute for Strategic Studies, Britain alone accounts for around 25% of spending on defence equipment procurement among EU countries. Its spending on defence investment is echoed only by France. According to the Institute, “It is among the two largest R&D spenders, along with France. It is notable that the UK and France are also in a league of their own when it comes to defence-investment spending – procurement and R&D – both in terms of absolute spending levels and the average percentage of defence spending that goes towards these categories each year.”

The British Army and Royal Navy rely mainly on equipment developed and made in Britain, such as the Challenger 2 main battle tank, the AS90 self-propelled artillery piece and, by and large, all naval vessels. It’s different for aircraft and helicopters, however, where the UK mostly uses equipment developed within multinational European projects, such as the Eurofighter Typhoon and Airbus A400M transport aircraft. It also buys from the United States. UK-made equipment, such as the Agusta Westland Lynx has also been sold to several other EU countries existing procurement. Britain also supplies parts, such as the power shafts, turbines and turret of the AS90 for the new Polish self-propelled artillery systems. It is hoped that Brexit will not impact on existing procurement projects, although it may affect supply-line issues. It’s harder to predict how large a part the UK may be allowed or invited to play in future European military procurement projects. According to the International Institute for Strategic Studies, “The UK’s defence-industrial competences are only partly integrated in the European defence sector; the relationship is immature and slightly asymmetric, with the UK somewhat more dependent on the continental defence-industrial base than vice versa.” The report continues: “In particular, regulations and standards tied to the Single European Market (SEM) and their linkages to technology, R&D, the labour market, intellectual-property rights, all the way to transfers and tariffs, present a vulnerability.”

But in terms of personnel commitment, the UK seems largely disinterested in EU missions. In 2017, the UK had more than 13,000 military personnel deployed on overseas missions or at overseas bases. It had less than 100 serving in EU operations, below what many small countries contribute. The Institute explains that: “The CSDP has never been central to the UK in operational terms because the remit of CSDP operations, essentially crisis management, has only ever reflected a limited part of the overall British level of ambition.” Strangely, in February 2018, Earl Howe, Minister of State for Defence, told the UK Parliament’s Defence Select Committee that: “the Government would like the EU to issue the UK with a standing invitation to contribute to CSDP operations and missions, to be exempt from the common costs for civilian missions and non-executive military operations and to have an agreement that enabled UK contributions to the EU force catalogue.” The exchange was reported in a House of Commons Briefing Paper. When asked whether the UK’s entire force catalogue would be on offer to the EU for use in CSDP missions and operations, “the Minister accepted there would be an opportunity cost which would have to be reconciled as assets committed to a CSDP operation or mission would no longer available to other missions. However, he also noted that CSDP operations and missions could be useful to UK foreign policy objectives, highlighting that in some cases EU-badged missions were considered to be acceptable in a way that NATO-badged missions were not.”

LEAVING THE DOOR UNLOCKED

Brexit, especially without a deal, may well impact on Britain’s defence manufacturers, if not directly on its military, as a blog for the London School of Economics (LSE) points out: “a no deal Brexit will have negative consequences for British manufacturing, including the space, aerospace and defence industries. Delays and additional costs to exports may endanger British firms’ participation in major international supply chains.” But the report also highlights another and possibly greater threat in terms of civilian security: “a no deal Brexit would have considerable impact on the UK’s internal security,” the authors claim, “in particular on police and judicial authorities’ capacity to address issues such as organised crime and terrorism, and on the UK’s role as a leading country in the area of security, including its ability to propose new instruments and shape EU decisions so as to align them with its national interests. In fact, one could even go as far as to say that a no deal Brexit constitutes a substantial threat to UK security given the current critical and unprecedented levels of organised crime activities, as well as the continued severe level of international and domestic terrorism.”

In terms of fighting crime and terrorism, Britain has benefited from its membership of Europol, the EU’s police cooperation and coordination body, and from the use of European arrest warrants. That was how one of the four terrorists who set off bombs in London in July 2005 was brought back to face trial. Osman Hussein had escaped to Italy, apparently unaware that a simple European arrest warrant could be issued to bring him back to Britain without the rigmarole of extradition proceedings. Along with his fellow conspirators, Hussein faced a British court in 2007 and was given a life sentence with a minimum term of 40 years in prison. Without a Brexit deal, Britain will lose not only the use of the European Arrest Warrant but also access to the Schengen Information System, the European Criminal Record System and membership of Europol and Eurojust. The corollary is, of course, that other EU member states will lose access to British intelligence sources, said to be among the best.

It was only on 12 December 2019 that Eurojust became a fully-functioning EU agency. “Eurojust today heralds a new phase in its development, as it officially becomes the European Agency for Criminal Justice Cooperation, with the application of the Eurojust Regulation as the new legal basis,” said its website. Just as Europol involves police cooperation, Eurojust helps lawyers, courts, lawmakers and justice systems to work together. “The new Regulation will make Eurojust fit for the purpose of fighting increasing levels of cross-border crime, with an Executive Board dealing with administrative matters and giving the College of prosecutors from all Member States more leeway to focus on the continuously rising number of criminal cases.” Britain will no longer play a part in these agencies, despite previously arguing that continued UK participation is “vital” and must not be weakened. The Defence Select Committee was assured that the aim remains to find a “workable way of ensuring we do not see a major drop in interactions with Europol.” The Britain who headed Europol, the urbane, calm and highly-effective Rob Wainwright, has already stepped down and future relations with Europol will be subject to negotiation.

STILL HOSTILE

The authors of the LSE blog express concern that Britain is cutting itself off from intelligence-sharing and police and judicial cooperation at a difficult time. “Against a background of wide-ranging police cuts (namely the loss of 44,000 police officer jobs since 2010) and the accumulation of austerity effects, the rapidly growing levels of insecurity are having a clear impact on the everyday safety of the UK population, with serious and organised crime currently endangering more lives than any other national security threat,” they write. “Given that these problems are transnational in nature, the key to addressing them lies on intelligence and information exchange, rather than on the reinforcement of borders as has been occasionally expressed.” But, as mentioned earlier, that cuts both ways: Britain’s former partners will be more at risk too.

Some of the arguments put forward in favour of leaving the EU centred on the reinforcement of borders, or to put it another way, how to deter or expel illegal migrants. It struck a chord in areas suffering high unemployment following industrial decline. Immigration is a problem for all EU member states, especially Germany, but nobody has yet come up with a workable, humane response. At present, responsibility for where immigrants can apply for asylum is covered by the Dublin III Regulation, under which an asylum-seeker can be sent back to wherever their arrival in the EU was first recorded. The aim is to deter and prevent immigrants from cherry-picking their preferred place of asylum, if it’s granted, or making multiple applications. In effect, it means most asylum-seekers are returned to the places they managed to reach first, usually Greece, Italy or Spain. The fingerprints of asylum seekers are stored in the Eurodac database, another EU facility to which a post-Brexit Britain may lose access. The data record prevents applications from being submitted in different countries. However, if there is no deal the UK will no longer participate in Dublin III and instead the Immigration, Nationality and Asylum (EU Exit) Regulation 2019 will take its place, coming into force on the day Britain leaves. This will revoke the Dublin arrangements although the government claims that existing family reunion applications “will be processed”.

Minister of State for Security at the Home Office, Brandon Lewis, said: “We want a close future partnership to tackle the shared challenges on asylum and illegal migration. Section 17 of the European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018 commits the Government to seek to negotiate an agreement with the EU which allows for unaccompanied asylum-seeking children in the EU to join family members lawfully present in the UK, where it is in their best interests. This commitment stands whether we leave the EU with or without a deal. Effecting transfers relies on an agreement being in place and we endeavour to negotiate such an agreement as soon as possible.” Lewis also pointed out that a UK asylum application may still be considered inadmissible if the applicant had travelled through an EU country, although this will require changes to UK immigration rules, to “ensure continuity of approach by widening the scope of other third country rules to deal with these cases”. The previous prime minister, Theresa May, introduced a “hostile environment” for illegal immigrants (and effectively for all immigrants), with trucks driving around bearing large placards with a “go home” message. The policy involved legislative measures to make life difficult for anyone living in Britain without a provable right to remain which resulted, unintentionally, in 80 people from the Windrush generation – West Indians invited to Britain to increase the workforce in the aftermath of the Second World War – being deported incorrectly and many more being forced to leave, often because papers for certain years of their decades-long stay were missing. The Home Office refused to acknowledge that the 1971 Immigration Act had given these people indefinite right to remain, even after it emerged that it had destroyed the immigrants landing cards. Far from contrite, the Home Office set up an interim hardship scheme for those worst affected but as of May last year, only nine people had received any benefit. Based on the evidence to date, anyone hoping for a hint of regret or sympathy at ministerial level – or, indeed, the right to family reunion – may have a long wait.

THE LONG GOODBYE

It looks as if a post-Brexit Britain may plough a lonely furrow after Brexit, especially a no-deal Brexit, where security and defence are concerned, although it may, of course, be a successful and thriving furrow. The fact remains, though, that just as the EU begins to see a need for a defence strand to the Union and to fear that the United States is no longer interested in Europe, Britain is sailing off into the sunset. The UK’s military will see little effect, but its defence industry almost certainly will, excluded from research and development projects and cut off from EU funding for them, with the prospect of slower and more complicated import and export regimes for Europe. 11% of UK arms exports were to EU countries; in fact, Britain accounted for 4% of EU countries’ total arms imports. Arms made in the EU also accounted for 23% of Britain’s arms imports. There is more concern over the effects Brexit may have on police and judicial cooperation, however. If the UK is also excluded from security bodies and intelligence sharing, it could put British citizens’ lives at risk.

As the EU’s Brexit negotiator, Michel Barnier, pointed out to the European Defence Agency in November 2019: “The international context is more challenging than ever. Unpredictability and instability are the new normal,” he said, before listing the challenges. “Russia continues to assert its influence in the region and beyond, sometimes in contradiction with international law. China is engaging in strategic competition and promoting its alternative economic model around the world. The United States increasingly chooses the path of unilateralism to defend its interests. Trade tensions and technological competition are new drivers of international relations, not to mention the spread of terrorism and global instability. This global picture has informed our approach to Brexit since the very beginning.” And just in case any other member state may be thinking of following Britain out of the door, he added: “In the current volatile geopolitical context, we need to focus on the unity of the EU27; the solidarity between Member States. In the European Union, no Member State walks alone.”

Britain, however, seems determined to stroll away, possibly with an eye on the United States as a partner, although that threatens to be a totally asymmetric relationship. Furthermore, the Trump administration seems uninterested in Europe (and Britain); Russia and China are not. Britain can continue to develop military matériel with France under the Lancaster House Treaties, signed in London in 2010 by David Cameron and Nicholas Sarkozy, but Brexit is straining cross-Channel relations. A former UK National Security Adviser, Lord Peter Ricketts, has warned that it “will change the context and create the risk of the two countries drifting apart.” The security risks don’t end when Britain leaves, nor does the fact change that an external threat to Paris, Berlin or Tallinn will also be an external threat to London. Britain and mainland Europe will continue to face the same threats in an unstable world. Michael Leigh, a Former European Commission director-general of enlargement, wrote in a blog for the International Institute for Strategic Studies, that the risks remain for every country in Europe, in or out of the EU. “These include the risk of war with Iran and the threat of secondary US sanctions on European companies; a tug of war between Beijing and Washington on trade and technology, with Europe, including Britain, in the middle; ineffectual US efforts to impose a skewed Middle East settlement in Europe’s backyard; continued Russian aggression in Ukraine; and Chinese, Russian, Turkish and Saudi intervention in the Balkans that could further destabilise a region often seen as Europe’s inner courtyard.” I’m reminded of comic actor Kenneth Williams’ remarks when playing Julius Caesar in the film Carry On Cleo: “Infamy! Infamy! They’ve all got it in for me!” It’s still true but it’s no longer funny, I’m afraid.

Jim Gibbons

Click here to read 2020 February’s edition of Europe Diplomatic Magazine