President of Chile Michelle Bachelet at the Women’s Day Commemoration in Lo Prado in 2018 © Gobierno de Chile

On the soccer field of a village about one hundred kilometres from Santiago de Chile, the thermometer has climbed to 36°C. In the middle of the southern summer, Michelle Bachelet harangues the crowd and promises “a country without exclusion, without discrimination, with the same rights for women as for men”. Her round glasses and a simple orange blouse make her look like a school principal. But even if the race was tight, Michelle Bachelet, the candidate of the centre-left Democratic Concertation Party, in power since the return of democracy in 1990, was given as the favourite for the second round of the presidential election on this Sunday afternoon, in January 2006.

At 54 years of age, this paediatrician who claimed to be “a citizen like any other but with a vocation for public service”, was poised to become the first woman president in the history of Chile. In a conservative society where the Catholic Church is all-powerful, it was unthinkable until a few years back that a woman could succeed the socialist president Ricardo Lagos in March 2006. “I have all the sins imaginable: I am a woman, I am a socialist, I am divorced and I am agnostic”, joked “Michelle”, as Chileans affectionately called her. The press regularly referred to the “Bachelet phenomenon”.

But Michelle Bachelet is also a courageous woman. She was an underground activist for many years, and following the military coup of 11 September 1973 when General Augusto Pinochet and his junta overthrew the elected socialist government of Salvador Allende, she took great risks helping to hide activists and the families of prisoners.

Born on September 29, 1951, in Santiago, she is the daughter of Alberto Bachelet, an air force general, and Angela Jeria, an anthropologist. On her father’s side, one of her ancestors left France for Chile in 1869. He was a winemaker from the village of Chassagne-Montrachet in the Côte d’Or, which she visited in May 2009.

Michelle Bachelet began her medical studies in 1970 and joined the Chilean Socialist Party at that time. Her father, who was close to President Salvador Allende, was appointed head of the Food Distribution Office. A few years later, he was arrested, imprisoned, and tortured by the military junta led by Augusto Pinochet. He died in March 1974, probably as a result of mistreatment while in detention. In January 1975, Michelle and her mother were also imprisoned and tortured in the infamous Villa Grimaldi, one of the most sinister prisons in Santiago.

Torture, says this politician who raised her three children alone, “is terrible, especially from a psychological point of view: it humiliates you”. As soon as they were released, they left Chile, first for Australia, then for East Germany where Michelle continued her studies at the Humboldt University in Berlin. There, Bachelet married Jorge Dávalos, a Chilean architect who had also fled the Pinochet regime. They had a son, Sebastián, before the family returned to Chile in 1979.

Michelle Bachelet completed her medical degree at the University of Chile, graduating in 1982. She had a daughter, Francisca, in 1984, then separated from her husband about 1986. As Chilean law made divorce very difficult, Bachelet was unable to marry the physician with whom she had her second daughter in 1990. As a surgeon, she began working in paediatric public health at the Roberto del Rio Children’s Hospital, as well as a number of NGOs.

Following the re-establishment of democracy, she worked as an advisor in the office of the Secretary of State for Health from 1994 to 1997. Since she was also interested in defence issues, she studied military strategy at the National Academy of Political and Strategic Studies (ANEPE) in Chile, and then at the Inter-American Defense College in the United States. In 1998, she was appointed advisor to the Minister of Defence. She also studied military science at the War Academy of the Chilean Army. Michelle Bachelet, who is a proficient multilingual was already well-known for her ability to work long hours without getting much sleep.

FROM PINOCHET’S JAILS TO THE PRESIDENCY OF CHILE

Michelle Bachelet began her career in the public sector in the early 1990s. She worked for the Ministry of Health and humanitarian organisations such as the WHO, GTZ (German Technical Cooperation), and PAHO (Pan American Health Organisation). Following her position as an advisor in the Cabinet of the Secretary of State for Health in 1997, she became an advisor in the Ministry of Defence in 1998. In 2000, she became Minister of Health, and in 2002 Minister of Defence, a ministerial portfolio never held by a woman in Chile or Latin America.

Due to her growing popularity, and with the backing of President Ricardo Lagos, who was still in office in 2004, Michelle Bachelet became the presidential candidate of the Democratic Concertation, a coalition of socialists, radicals, and Christian Democrats that was in power since 1990. She faced Joaquin Lavin, supported by the Independent Democratic Union (UDI, right), Sebastián Piñera, supported by the National Revolution (RN, centre-right), and Thomas Hirsch (extreme left).

January 15, 2006, was a historic day; for the very first time, a woman was elected president of Chile. Michelle Bachelet won with 53.5% of the votes against 46.5% for her right-wing rival, the billionaire businessman Sebastián Piñera. Hundreds of thousands of Chileans, dancing with joy and waving multicoloured flags, invaded the centre of the capital, Santiago, in the evening.

Her election was a great victory for the Democratic Concertation, of which she was the candidate. This centre-left coalition formed by Christian Democrats, Socialists, and Radicals won the presidency of the Republic for the fourth consecutive time since the return of democracy in 1990. The outgoing president, the socialist Ricardo Lagos still enjoyed a popularity rating of 75%.

Michelle Bachelet is the fifth woman in Latin America to become president, but the first-ever elected by direct universal suffrage. The previous four were married to either former presidents or to politically prominent and influential husbands (Janet Jagan of Guyana, 1997 – 1999. Mireya Moscoso of Panama, 1999 – 2004. Violeta Chamorro of Nicaragua, 1990 -1997 and Isabel Perón, 1974 -1976, who was vice-president to her husband). As she had promised during her campaign, her government was indeed composed of as many women as men. Following a constitutional revision, she remained president until 2010; the Chilean constitution does not allow a candidate to run for office in two consecutive elections. She, therefore, did not take part in the presidential elections of December 2009.

Michelle Bachelet’s presidency was marked by significant social reforms, notably in health care, retirement benefits, and housing. There was the signing of free trade agreements with countries from Asia and Oceania as well as sustained efforts at diplomatic rapprochement with neighbouring countries, Bolivia, Argentina, and Peru.

On the eve of leaving office, an opinion poll gave her 84% support, the highest figure ever recorded by a Head of State in Chile at the end of a presidential term. On March 11, 2010, Sebastián Piñera, a centre-right candidate whom she had ousted in the second round of elections in 2006, succeeded her as president.

In 2013, Michelle Bachelet ran for the presidency of Chile again. This time, she won with 62% of the votes against the conservative candidate, Evelyn Mattei. This was a long-awaited return but a major challenge for Michelle Bachelet who promised a series of wide-ranging measures to reduce inequality and reform the education system.

She was, however, committed to maintaining the fiscal discipline that had characterised Chile since the early 1990s. Her pragmatic and liberal approach to the economy brought her closer to her Brazilian counterpart Dilma Rousseff than to the leaders of Venezuela or Argentina within the Latin American left. Chile, whose economy was growing at an annual rate of more than 5%, had experienced spectacular development over the past twenty years, which allowed considerable progress to be made towards eradicating extreme poverty. But inequalities persisted among its 16.6 million inhabitants; these were at the heart of the student protest movement of 2011.

Michelle Bachelet also announced her intention to reform the Constitution which was inherited from the dictatorship of General Augusto Pinochet (1973-1990) and to decriminalise abortion in cases of rape or danger to the health of the mother or the unborn child.

During this second term, however, she encountered several difficulties, notably due to the decline in the value of copper, the country’s main export resource. Her term in office was also marred by several political scandals. In 2016, one year after the resignation of her son in a context of influence peddling and hidden financing of the presidential campaign, her popularity rating eventually fell to 22%, a score not seen since the end of the military dictatorship.

However, if domestically her record was denounced by a majority of Chileans, internationally, the prestige of Chile’s first-ever female president remained intact. Forbes magazine, in a ranking published in November 2017, considered her the most powerful woman in the region and fourth in the world.

Michelle Bachelet left the presidency at the end of her term in March 2018 and was succeeded by Sebastián Piñera, a long-time political opponent and her predecessor.

THE NEW VOICE OF INTERNATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS

If heads of state and diplomats around the world were hoping that the commitment of the person occupying the post of UN High Commissioner for Human Rights would remain intact after the replacement of the Jordanian diplomat Zeid Ra’ad Al-Hussein, by Michelle Bachelet, they could celebrate.

In her first speech on 10 September 2018 in Geneva, for the opening of the 39th session of the Human Rights Council, the twice president of Chile and former director of the UN Women agency, pointed out the main concerns of the moment and did not spare the countries guilty of the worst violations of international humanitarian law. She put forward her political and diplomatic qualities and ambitions, indicating that she will be “attentive to governments” and will seek “consensus” between States. Her predecessor had been strongly criticised for having alienated many countries through his fiery denunciations.

The new High Commissioner for Human Rights, appointed by UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres, recalled however that she was a political prisoner and the daughter of a political prisoner, that she was a refugee and that she was a doctor for child victims of torture in Chile. She paid a vibrant tribute to her predecessor Zeid Ra’ad Al-Hussein and left little doubt about her commitment to human rights.

The most strident comment in the speech was directed at Myanmar where thousands of Rohingya Muslims had allegedly been murdered in 2017 and from where an estimated 700,000 have been deported to Bangladesh. She highlighted the “extremely shocking findings” of U.N. investigators, who had recommended that international justice prosecute six Myanmar military leaders for “genocide and crimes against humanity.” She welcomed the decision of the International Criminal Court (ICC) to take up the crimes committed in Myanmar and called on the Human Rights Council to establish an independent international body to collect, preserve and analyse evidence of the most serious international crimes to expedite trials.

The High Commissioner listed a variety of armed conflicts of particular concern to her, including the ongoing offensives in northern Syria and the war in Yemen. And she singled out dozens of countries where human rights abuses are an ongoing concern for her team.

She also spoke at length on the issue of migration, denouncing the attitude of some Western countries dominated by governments with anti-migration policies that violate human rights, including the United States and, Europe, Hungary, Italy, and Austria. “Erecting walls, deliberately generating fear and anger among migrants, depriving migrants of their basic rights” is a policy that only offers, according to her, “more hostility, misery, suffering, and chaos”. Michelle Bachelet recalled that as far back as humanity goes, people have always moved in search of refuge and opportunity, estimating that there are currently 250 million people in this situation, on a planet of 7.5 billion inhabitants.

CHINA IN THE CROSSHAIRS

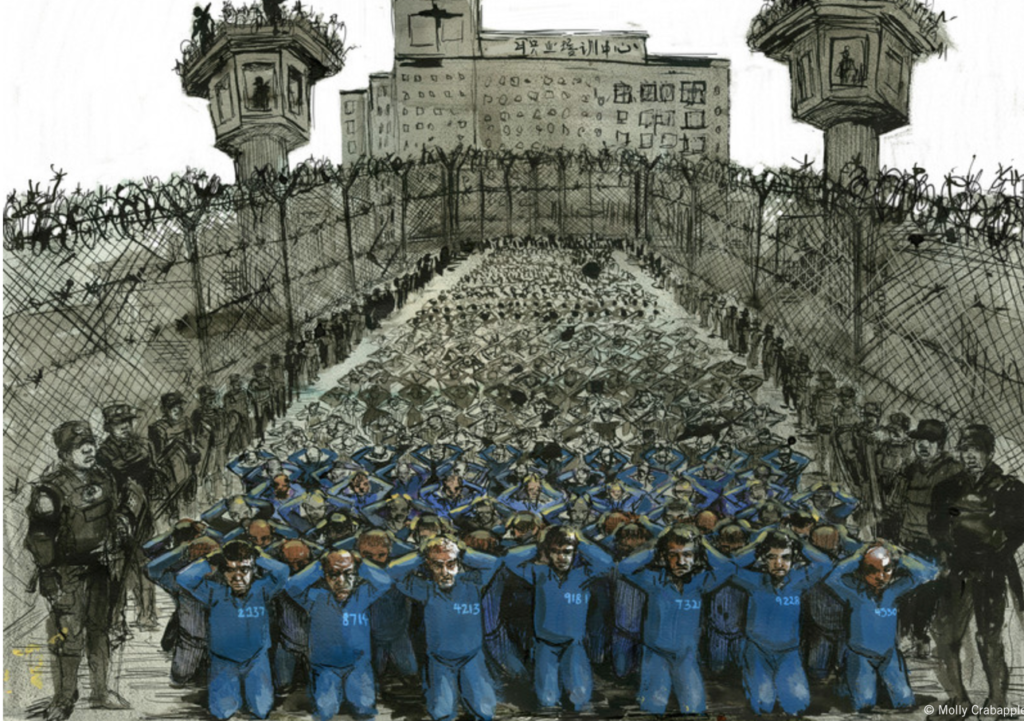

In a written version of her speech handed out to the press but not read in full, she criticised China for “deeply disturbing allegations of large-scale arbitrary detentions of Uighurs,” after an accusation in August 2018 to a U.N committee that one million members of the Muslim minority in the Xinjiang region are being held in camps.

As expected, China’s reaction was not long in coming. Reacting to the words of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights expressing concern about arbitrary detentions on a large scale of Uighurs by China, Beijing promptly reminded Ms. Bachelet to respect the sovereignty of the country. “China urges the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights to strictly adhere to the mission and principles of the UN Charter, respect China’s sovereignty, carry out her missions honestly and objectively, and not listen to biased information,” Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman Geng Shuang said at his daily press briefing.

According to the Chinese government, the autonomous region of Xinjiang in western China faces the threat of Islamists and separatists who are stirring up tensions between the Uighurs, a Muslim and Turkic-speaking minority that considers the region its own, and members of China’s majority ethnic group, the Hans. Security measures in Xinjiang have been stepped up considerably, with the establishment of police checkpoints for identity checks, re-education centres, and massive DNA collection campaigns.

In 2020, the High Commissioner reiterated her hopes of gaining “significant access” to Xinjiang, where “reports of serious human rights violations continue to emerge”. China denies the figure of one million Uighurs in detention and speaks rather of vocational training centres to support employment and combat religious extremism.

In Geneva, Ms. Bachelet repeatedly called on Beijing for full access to Xinjiang. And in late February 2021, she reiterated her call for a full and independent assessment of the human rights situation in the region. But human rights activists are continuing to call on the United Nations to announce tougher measures.

THE HIGH COMMISSIONER’S CHINESE CONUNDRUM

First, there was Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus. At the start of the Covid-19 pandemic, the head of the World Health Organisation was accused of being too close to Beijing. After a visit to Xi Jinping at the Great Hall of the People in January 2020, he praised China for its “speed,” “efficiency” and “transparency.” Today, it is another UN agency head who is in the sights: Michelle Bachelet.

The UN High Commissioner for Human Rights has raised questions about her attitude towards Beijing, which is considered too conciliatory. If she willingly intervenes on CNN and other major broadcasters to express herself about Ukraine, she is less prolix when it comes to China. On 13 May, Uighurs who had gathered on the Place des Nations in Geneva urged her to consult them before she visited China, or even to postpone it if the conditions for unhindered access are not guaranteed.

Since taking office in 2018, Michelle Bachelet has not issued a single press release on Xinjiang. She did settle for one in Hong Kong in June 2020. A report on Xinjiang has been shelved in the offices of the High Commissioner for Human Rights without anyone knowing why. This has angered several human rights NGOs and several diplomatic missions.

Michelle Bachelet’s highly controversial visit to China, from 22 May to 27 May, was the first for a High Commissioner for Human Rights since Louise Arbour in 2005. This was also a politically risky undertaking, as it is still unclear whether the former Chilean president will seek a second term at the head of the OHCHR as of September 1.

DISMAY AND CODEMNATION AS RUSSIA ATTACKS

“The Russian invasion on 24 February 2022 has plunged Ukraine into a humanitarian and human rights crisis that has devastated the lives of civilians across the country and beyond”, UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Michelle Bachelet said on 22 April 2022, calling on all parties to respect international human rights law and international humanitarian law, especially the rules governing the conduct of hostilities.

“During these eight weeks, international humanitarian law has not only been ignored but has been set aside,” Bachelet said. Russian armed forces have indiscriminately bombed and shelled populated areas, killing civilians and destroying hospitals, schools, and other civilian infrastructure. These are actions that may amount to war crimes. “What we saw in government-controlled Kramatorsk on April 8, when cluster munitions struck the train station, killing 60 civilians and injuring 111 others, is emblematic of the failure to respect the principle of distinction, the prohibition of indiscriminate attacks, and the precautionary principle enshrined in international humanitarian law,” said Bachelet.

The United Nations Human Rights Monitoring Mission in Ukraine (HRMMU) has documented what appears to be the use of weapons with indiscriminate effects, causing civilian casualties and damage to civilian property, by Ukrainian armed forces in eastern Ukraine. From February 24 to April 20, the HRMMU documented and verified 5,264 civilian casualties – 2,345 killed and 2,919 injured. Of this total, 92.3 percent (2,266 killed and 2,593 injured) were recorded in government-controlled territory. Some 7.7% of casualties (79 killed and 326 wounded) were recorded in the Donetsk and Luhansk regions controlled by Russian armed forces and affiliated armed groups. “We know that the real numbers will be much higher as the horrors inflicted in areas of intense fighting, such as Mariupol, are revealed,” said the UN human rights chief. During a mission to Bucha on April 9, UN human rights officers documented the unlawful killing, including by summary execution, of some 50 civilians. “Almost every Bucha resident our colleagues spoke to told us about the death of a relative, neighbour, or even a stranger. We know that there is still a lot of work to be done to get to the bottom of what happened there, and we also know that Bucha is not an isolated incident,” said the High Commissioner.

The HRMMU has received more than 300 allegations of killings of civilians in towns in the Kyiv, Chernihiv, Kharkiv, and Sumy regions, all under the control of Russian armed forces, in late February and early March. The intentional killing of protected persons, including summary executions, constitutes gross violations of international human rights law and serious violations of international humanitarian law and amounts to war crimes. Allegations of sexual violence against women, men, girls, and boys by members of the Russian armed forces in Ukraine are increasingly surfacing. The HRMMU has received 75 allegations, the majority from the Kyiv region. It is investigating each allegation but because survivors may not be willing or able to be interviewed, this remains a challenge.

In besieged cities, the mortality rate has particularly increased beyond the direct victims of weapons. The High Commissioner called on the parties to the conflict to investigate all violations of international human rights law and international humanitarian law allegedly committed by their nationals, armed forces, and affiliated armed groups, by their obligations under international law. “Civilians are suffering immeasurably and the humanitarian crisis is critical,” said Michelle Bachelet, noting that people often lack basic necessities. “But above all, they need the bombs to stop falling and the guns to be silenced,” she pleaded.

DENOUNCING THE CULTURE OF IMPUNITY

If as yet no sanctions have been taken against the State of Israel following the death of the Al-Jazeera journalist, Shireen Abu Akleh killed by Israeli forces in the West Bank, the United Nations does not intend to remain silent. It condemns with the utmost firmness, a murder that, once again, aggravated the already tense relations between the Hebrew State and Palestine.

In a statement published on its website on May 14, the UN denounced “a culture of impunity” and called for the immediate opening of an investigation to determine the origin of the shooting that killed the Al-Jazeera journalist, who was very popular with Palestinians.

Thus, on May 14, the United Nations Commission on Human Rights, headed by Michelle Bachelet, demanded the opening of an investigation to hold Israeli law enforcement agencies accountable. In the statement, Bachelet does not mince her words: ”I am deeply saddened by the events taking place in the occupied West Bank, including East Jerusalem. Videos showing Israeli police attacking relatives of the deceased in the middle of the funeral of journalist Shireen Abu Akleh on Friday 13 May were shocking,” she said.

And she was not the only one. On May 13, US Secretary of State, Anthony Blinken, also reacted on Twitter, saying he was “appalled” by the images circulating on social networks showing Israeli police beating up Palestinians who had come to attend the funeral of the Palestinian journalist.

Michelle Bachelet added that all the indications are that the use of force by the Israelis was unnecessary and should be investigated immediately and that responsibility must be established for the murder not only of Shireen Abu Akleh but of all those killed and injured in the occupied Palestinian territories.

A SITUATION OF PROFOUND GRAVITY

In December 1948, at the Palais de Chaillot in Paris, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was proclaimed and adopted by the 58 member states that constituted the General Assembly of the UN. The extraordinary vision and resolve of the drafters produced a document that, for the first time, articulated the rights and freedoms to which every human being is equally and inalienably entitled. Available in more than 500 languages and dialects, the Declaration is the most translated document in the world — a testament to its global nature and reach. It was meant to provide a foundation for a just and decent future for all and to give people everywhere a powerful tool in the fight against oppression, impunity, and affronts to human dignity

However, seventy-four years on, it must, unfortunately, be concluded that the world is still witnessing wide-scale violations of freedoms, the use of terror, crimes against humanity, the brutal repression of social movements and minorities, and the massive and deliberate violations of civilian populations.

It, therefore, came as no surprise when, at the 49th session of the Human Rights Council in February 2022, Michelle Bachelet called for strong leadership in the face of a “deeply serious” situation and declared: We have experienced periods of profound gravity in history that have divided the course of events between a “before”, and a very different and more dangerous “after”. We are at such a turning point now. The remarkable progress made over the past two decades in every region to limit conflict, reduce poverty, and expand access to education and other rights is being severely threatened”.

Weakened by the pandemic, divided by growing polarisation, affected by increasing environmental damage, and weakened by online disinformation, hatred, attacks on democracy, and disregard for the rule of law, many societies around the world are plunging into increased repression and violence, growing poverty, anger, and conflict.

The Russian army began its invasion of Ukraine shortly before 4 a.m. on February 24, triggering what appears to be the worst war on the European continent since 1945. Massive bombardments by aircraft, cruise, and ballistic missiles targeted military sites and ammunition warehouses throughout Ukraine, including far to the west of the country. Residential areas have also been badly hit. Millions of civilians, including the vulnerable and elderly, were forced to huddle in various forms of shelter, such as subway stations, to escape the explosions.

This war is a turning point in modern history, and it will most certainly have lasting consequences. It is a watershed moment. Yesterday’s certainties are gone. Today, the world faces a new reality that no one chose. It is a reality that Vladimir Putin forced upon the world, including his own country.

In her speech, Michelle Bachelet went on to add: “Over the next three days, an unprecedented number of dignitaries will participate in this high-level debate. This is a vital opportunity to unite and take action at this grave and decisive moment. In doing so, I ask first and foremost that we all place the world’s people – their common and universal rights and aspirations – at the heart of the debate”.

NOTHING CAN EVER BE FULLY TAKEN FOR GRANTED

Even though almost all countries are now members of the United Nations, all sorts of threats to human rights are still present. In 2018, German Chancellor Angela Merkel went so far as to doubt that the Universal Declaration of Human Rights could still win the support of the majority of member countries as it did in 1948. This declaration was made more than a year before the sanitary, economic and humanitarian crisis that the world experienced. Although not enough time has passed to allow for an assessment of the long-term impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic and its management by various states, many international institutions are already pointing out that the crisis could accentuate existing patterns of human rights violations and discrimination throughout the world:

UNICEF: “It could expose children and women to increased risk of violence and exploitation”

IFJ (International Federation of Journalists): “It could compromise press freedom”

UNESCO: “It could jeopardise access to quality education for all, and increase inequality”

Amnesty International: “It could lead to increased persecution of human rights activists”

UN: “It could jeopardise equal access to health care and services”

Human Rights Watch: “It could lead to an increase in racist and xenophobic attacks”

Human rights are best served when peace, social justice, and the rights of the vulnerable are defended…When all forms of discrimination related to age, gender, race, ethnicity, religion, sexual orientation, culture, or disability are combatted…When human dignity is placed above all else.

Eleanor Roosevelt, wife of former US President Franklin D. Roosevelt, and tireless human rights activist, famously declared in 1958: “After all, where do universal human rights begin? They begin close to home, in places so close and so small that they cannot be seen on any map of the world (…) If rights are meaningless in these places, they will be meaningless elsewhere. If each person does not show the civic-mindedness necessary to see that they are respected in his environment, we must not expect progress on a world scale”.

‘Our Common Agenda’, the report by UN Secretary-General, Antonio Guterres in September 2021, calls for renewed solidarity among peoples and future generations; a new social contract rooted in human rights; better management of the critical issues of peace, development, health, and our planet, and a revitalised multilateralism capable of meeting the challenges of our time.

It is perhaps fitting to end with Michelle Bachelet’s declaration which came at the end of her speech on International Human Rights Day on 10 December 2021: “Equality is about empathy and solidarity. It is also about understanding that, because we are all part of humanity, the only way forward is to work together for the common good. This was well understood during the years of reconstruction after World War II. However, our failure to “rebuild better” after the more recent crises suggests that we have forgotten the clear and recognised solutions rooted in human rights and the importance of addressing inequalities.

Solutions that we must bring back to the forefront if we are to continue to make progress – not only for those who suffer from the gross inequalities that plague our planet but for all of us.