© Edm

Europe is a pretty good place to live: a variety of towns, cities and villages, varied types of work, a good range of shops and places of entertainment, any type of scenery you fancy and lots of things to do, sporting or otherwise. It’s a good place to simply relax, too. That’s probably why it has an in-built population of some 450-million people. Not all of them are European in origin, of course: almost 24-million are non-EU citizens, which amounts to 5.3% of the overall population. 38-million people were born outside the EU, according to the European Commission, while more and more people from all around the world are coming with the hope of staying, at least for a while, if not for the remainder of their lives. Even so, bearing in mind its vast size – 4,422,773 km² – there is a limit to how many people can live in it. That’s why the EU is obliged to turn away some of those who would like to move here, with or without their families.

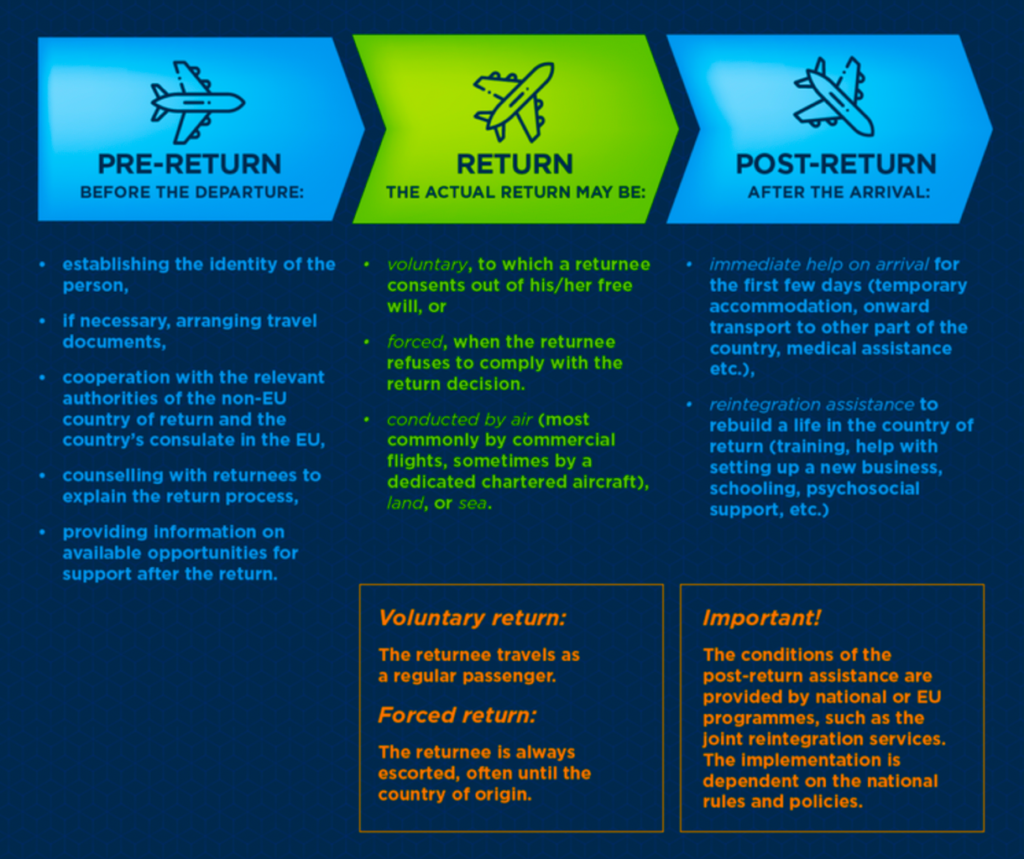

So back they go, homeward bound, whether they want to go or not. In some cases, it’s not so much “homeward bound” as “homewards, bound”, depending on the willingness of the migrant concerned to depart back to wherever they came from. There are various ways in which it can happen. The return can be voluntary, based on the migrant’s own decision. I won’t bother to go into the details of other forms of involuntary home-going, such as “spontaneous return”, “assisted voluntary return and reintegration (AVRR)” or “voluntary humanitarian return”, because the names are fairly self-explanatory and in the case of the last of those it may represent a life-saving measure for migrants who are stranded or being held in detention, for some reason. Then again, there’s also “forced return”, which has been described as “a migratory movement which, although the drivers can be diverse, involves force, compulsion, or coercion”. It’s not something anybody would choose to go through, according to the United Nations’ International Organisation for Migration (IOM).

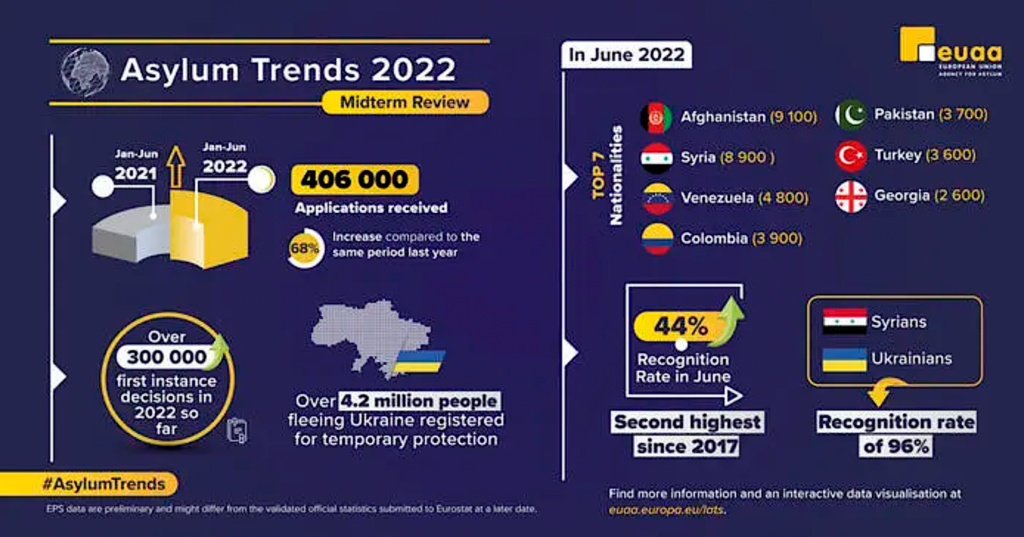

In June 2023, the EU received more than 83,000 migration applications. The largest group were Syrian nationals, followed by Afghans and then Venezuelans and Columbians. Some of this data may surprise you; it certainly surprised me. There was a surge in applications from Ukraine immediately following Russia’s unprovoked military invasion, rising from 2,100 in February 2022 to 12,185 in March 2022, but that has subsided somewhat in the months that followed, down to 1,065 in June 2023, mainly because those fleeing Ukraine as a result of Russian aggression get temporary protection. Meanwhile, the European Parliament has been discussing ways of welcoming Ukraine into the fold, just as soon as it settles its diplomatic disagreements with Poland and Hungary. But it’s generally agreed that for that to happen, the EU will have to change, too. One can easily understand why so many people are keen to leave Ukraine and move out of the range of Russian guns, but where are they going? Just as in other recent months, in June 2023, the highest number of would-be migrants tried to get into Germany which received 23,190 applications. Next came Spain with 16,075, France, with 12,475, and lastly Italy with 10,730 applicants. Those four continued to receive the highest number of first-time asylum applicants, accounting in total for 75% of all first-time asylum applicants in the EU.

In 2022, 420,100 asylum applicants were ordered to leave the EU, a 23% increase on the 340,500 ordered to leave the previous year. In 2022, 77,500 non-EU citizens were returned to a non-EU country corresponding to 18.5% of all return decisions issued during the year. That’s a decrease from 20% in 2021. For those hoping to begin a new life within the EU, it’s not all bad news: In 2022, nearly 1,700 Member States’ consulates received 7.6 million short stay visa applications lodged by non-EU citizens, which is an increase from 2.9 million in 2021 but still 55% fewer than in 2019. In total, 5.9 million short stay visas were issued and 1.3 million were refused, amounting to an EU-wide refusal rate of 17.9%. That’s an increase of 13.4% over 2021.

Return procedure explained by Frontex © Frontex

| WHY LEAVE?

In many cases the refusals stem from a lack of the proper documentation, but it’s hard to monitor it all accurately because the data are scattered across a number of different sources of recorded information and many of them are, at best, incomplete. The EU is currently trying to correct this oversight, although different countries use different definitions and different methods, and furthermore not all of the data is properly tracked. Millions of people every year are returned to their countries of origin, but not all of them are recorded at all, let alone accurately. According to the UN’s International Organisation for Migration (IOM), record-keeping was severely interrupted (as were many things, of course) by the COVID-19 pandemic. Lockdowns, travel restrictions, limited consular services and a number of other factors severely disrupted migration, along with record-keeping of cross-border movement. The IOM says that many countries lifted their various travel restrictions in 2021, but neither migration itself nor return-migration have returned to their pre-pandemic levels. In 2022, the numbers benefitting from the IOM’s Assisted Voluntary Return and Reintegration (AVRR) rose by 24% from 43,428 in 2021 to 54,001 in 2022, while the numbers making use of the voluntary humanitarian return service went up by an impressive (if slightly worrying) 139% from 6,367 in 2021 to 15,281 in 2022.

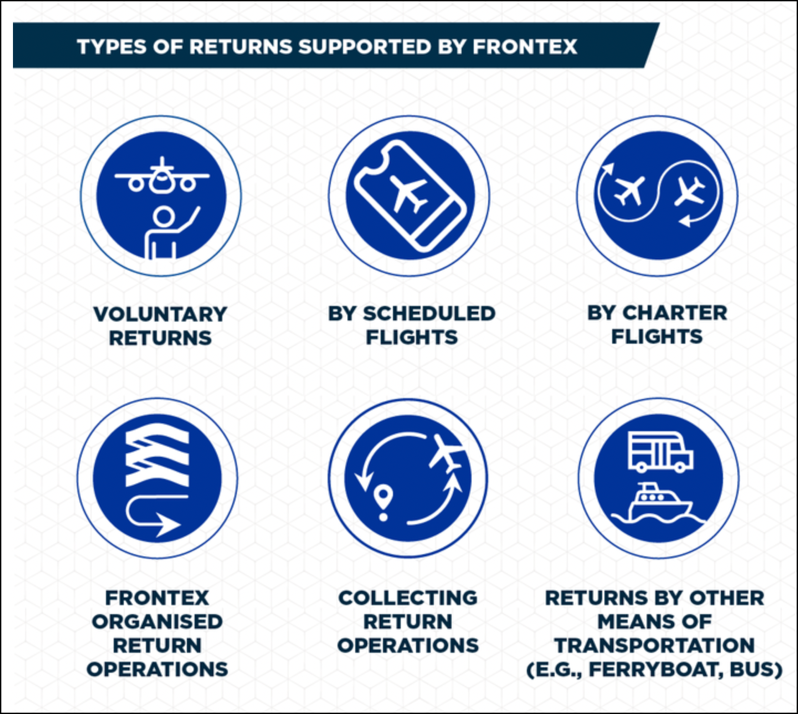

During the pandemic itself, the European Union Border and Coastguard Agency, Frontex, reported that travel restrictions and the reduction in consular services had impacted badly on return migration. Some 291,000 irregular migrants were given a “return decision” by EU member states in 2020, but only 61,951 people were actually returned, whether voluntarily or under compulsion, according to Frontex. In 2022, the number of people returned home with the support of Frontex in 2022, came to 24,850. The figures for the UK, which had just left the EU, are slightly odd. In 2021, 9,508 people left Britain in either an enforced or voluntary return, the lowest annual departure figure since 2012, which tends to suggest that those politicians and newspapers who argued that leaving the EU would reduce the number of migrants getting to the UK were simply wrong, as they have since been proved to have been about so many other things.

This is a restless world, where those hungry for control seek to take over regions or even whole countries, while citizens are batted between the warring parties like shuttlecocks in some kind of ghastly game of badminton. Look at Nagorno-Karabakh, for instance. It’s a territory extending to an area of around 4,400 square kilometres that is disputed between Armenia (which has the support of Russia) and Azerbaijan (supported by Turkey), both of which claim sovereignty. It was, of course, part of the old Soviet Union. The majority of its citizens identify as Armenian and now 28,000 or so of those living in Nagorno-Karabakh have fled as migrants towards Armenia, their supposed homeland. The ambitions of the few inevitably lead to the redistribution of the many, with all it involves in terms of lost lives, destroyed homes, deserted towns, killings, and hatred. It is, as always, a terrible business, but at least one can say, I suppose, that those currently fleeing Nagorno-Karabakh towards Armenia identify as ethnic Armenians and what’s more they’re not trying to get to poor overcrowded Lampedusa. It seems that the more powerful and ruthless world leaders simply can’t leave things alone, where borders and ethnicities are concerned.

Looking again at Europe’s problems with migration, there are a number of issues that need to be addressed, including the search for jobs. In 2022, 9.93 million non-EU citizens were employed in the EU labour market, out of 193.5 million persons aged from 20 to 64, corresponding to 5.1% of the total. The employment rate in the EU in the working-age population was higher for EU citizens (77.1%), than for non-EU citizens (61.9%) in 2022. The range of occupations taken by migrants to Europe makes interesting reading. We must not forget the issue of language, of course, that ever-lasting barrier to communication. Among non-EU citizens, some 11.4% work as cleaners and helpers, compared with just 2.9% of born-and-bred EU citizens. Another 7.3% of the non-EU citizens work in the personal services sector, while just 4.1% of native EU citizens do such work. You’ll find around 6.1% of migrants in building and related trades (but not as electricians) with a further 6% carrying out labouring work (unskilled) in mining, construction, manufacturing, and the transport sector. They tend to be under-represented in the fields of public administration, defence, social security, education and in work described as “professional, scientific and technical”, compared with native EU citizens.

| WHERE ARE WE GOING?

So how about the choice of home country for those restless souls who travel the world? Oddly, the country that has taken in the highest percentage of foreigners is Switzerland, with 30.2%, with Australia coming a close second at 29.2%. Strangely, Turkey comes last on that list with only 3.7% of its residents not being ethnically Turkish. Strange, that: Turkey is a very friendly and attractive country. But there are a great many conflicts in the world that inevitably lead to people seeking a new life somewhere safer, for themselves and for their families. According to official figures, at the end of 2021, less than 10% of all the world’s refugees and only a fraction of internally displaced persons were living in the EU. By mid-2022, as a result of the war in Ukraine, the share of refugees living in the EU increased to more than 20%.

For those people who oppose migration completely (the UK’s Home Secretary, Suella Braverman springs to mind here; her condemnation of the UN’s relatively compassionate rules on immigration and the treatment of migrants has come in for condemnation by many at the UN itself and earned the headline in the Guardian newspaper: “Smirking Suella trashes seventy years of human rights in thirty minutes”), please remember that without migration, the European population would have shrunk by half a million in 2019, given that 4.2 million children were born and 4.7 million people died in the EU; a sad statistic but none-the-less true. In 2020 and 2021, EU population actually shrank, due to a combination of fewer births, more deaths and less net migration. Europe could well be shrinking.

There is a further complication in relations between Armenia and Azerbaijan: most Armenians living in Armenia are members of one of the very oldest sects of Christianity: the Armenian Apostolic Church, founded in the first century and becoming, in 301 AD, the first branch of Christianity to be adopted as an official state religion. The picture in Azerbaijan is more complicated and nuanced, with 80% of the population adhering in principle to Shia Islam, giving the country the world’s second largest Shia population. Shia Islam was made the state religion in the 16th century, but its enforcement caused a rift with the Sunni Muslim community, and many Sunnis left the country. Perhaps I should explain that while Shia Muslim believe the Prophet Mohammad appointed a successor, Sunnis believe he did not. The two branches of Islam have been in conflict with one another for centuries with no possible settlement in sight. People in some parts of Azerbaijan, making up just 3% of the population, follow Orthodox Christianity, but even there you can find a schism: the Russian Orthodox Church was established following the Russo-Persian war in the 19th century, but there is also the Georgian Orthodox church, most of whose followers were converted from Islam. Adherents of all and any religion were persecuted, and their faiths suppressed during the Soviet era. And just in case that is not sufficiently complicated for you, Azerbaijan is reckoned to be one of the least religious Muslim countries in the world, with most citizens attaching little or no importance to religion and therefore not worshipping at all. There are other Christian groups to be found, including Armenian apostolic, Roman Catholic and Protestant, although even counting them all together they only make up some 1% of the population. A few other religious groups who make up only a tiny minority of the population, such as Jehovah’s Witnesses, Baptists, Hindus, Zoroastrians, Jews and members of the so-called Assemblies of God total only some 1,000 adherents. They have accused the Azerbaijan government of denying them the rights to worship in their own ways. There is no official state religion and 2% of the population are self-declared atheists. The two sides have met for talks in a bid to end the violence and settle Nagorno-Karabakh’s future but at the time of writing it’s by no means certain that any real progress was made. Azerbaijan’s representative told the meeting that Nagorno-Karabakh is now completely under their control, while their official news agency would only say that the talks had ended, not how nor with what conclusion.

But Nagorno Karabakh is not the region that is giving European leaders nightmares. It may have many citizens seeking a new life elsewhere among people they believe to be more like themselves and possibly even welcoming (if they’re lucky), but it won’t involve a lot of unseaworthy small boats, piloted by money-grubbing villains and crooks, trying to make their way across an increasingly unsafe Mediterranean on their way to Lampedusa and then on to Italy. There are three main routes used by migrants. The Western Mediterranean route takes migrants both by sea and land to the Spanish enclaves of Cueta and Melilla in Northern Africa. The migrants travel through Morocco and Algeria to reach their destination. Frontex tries to help Spain keep out those that should not be admitted. Migrants and asylum seekers also use the Central Mediterranean route to enter the EU on an irregular basis. They embark on long, dangerous journeys from North Africa and Turkey, crossing the Mediterranean Sea to reach Italy, and to a much lesser extent also Malta. Clearly this cannot go on for ever, so The EU established a joint migration task force with the African Union and the UN in November 2017, which aimed to pool efforts and enhance cooperation to respond to the many migration challenges in Africa and in particular in Libya.

The large majority of the migrants transit through Libya on their journey towards Europe. This has contributed to the development of well-established and disturbingly resilient smuggling and trafficking networks in Libya. However, the establishment of that joint migration task force with the African Union and the UN has made it possible to launch major assisted voluntary humanitarian return programmes and evacuation operations. The task force is currently exploring new measures and updated terms of reference to improve its effectiveness, including the expansion of its mandate and geographical coverage.

Even so, there have been tragedies, almost always avoidable. In June 2023, for instance, when the overcrowded trawler, Adriana, carrying some 750 migrants from Libya, was seen from a Frontex patrol plane to be in difficulties. Frontex informed the Greek and Italian authorities but no rescue teams were dispatched for eleven hours. Survivors (and there weren’t many) claimed that the Greek coastguard tried to take the Adriana under tow, causing it to capsize and sink, although the Greek authorities deny this. We’ll never know for sure because although some of those on board tried to film what was happening, the Greeks confiscated all mobile phones. Frontex had been ordered out of the zone by Greece, so can neither corroborate nor deny the story, although it’s not the first time that Frontex assets have been ordered away from a potential tragedy, with Frontex staff kept away from viewing so-called “push-backs”. In the case of the Adriana only 104 of the 750 passengers survived. That same month, Frontex released a formal statement, saying it was “shocked and saddened” by the shipwreck and offering its condolences to the families of the dead. It also stated that Frontex had been redirected to a distant part of the Aegean and that no Frontex facilities had therefore been on hand to help with a rescue, although it did not condemn anything Greece did (or did not do).

| ARE WE THERE YET?

In June 2018, EU leaders called for further measures to reduce irregular migration on the Central Mediterranean route. They agreed, amongst other things, to:

intensify their efforts to stop smugglers operating out of Libya or elsewhere, whilst continuing to support Italy and other frontline EU countries, increasing their support for the Libyan coastguard, creating humane reception conditions and the voluntary return to countries of origin of those migrants stranded in Libya. They also agreed to enhance cooperation with other countries of origin and transit, and on resettlement. In July 2019 the EU approved five new migration-related programmes in North Africa costing in total €61.5-million. The projects include protection and assistance for refugees and for vulnerable migrants, improvement of the living conditions and resilience of the poor beleaguered Libyans and the fostering of labour migration and mobility. These programmes have been adopted under the EU emergency trust fund (EUTF) for Africa, which was established in November 2015 to address the root causes of forced displacement and irregular migration and to contribute to the better management of migration. The large overall budget for the fund comes to more than €5-billion. In November 2022, due to the significant increase in migratory pressure on the route, the European Commission presented an EU Action Plan on the Central Mediterranean to address the many challenges migrants will face along the route. The Action Plan proposes twenty measures designed to reduce irregular and unsafe migration, providing solutions to the emerging challenges in the area of search and rescue and reinforcing solidarity, balanced against responsibility shared between member states.

The European Commission has long been concerned about migrants trying to escape from hardship or danger in their home countries who would like to get themselves and their families into the European Union. The Commission itself has announced six particular objectives, although they’re not exhaustive. Firstly, the Commission wants to protect those needing shelter. It would like to curb irregular migration. It considers it important to save lives at sea but also to secure the EU’s external borders; I’m not sure those two are mutually compatible. It wants to guarantee the free movement of people within the Schengen area. In order to help the migrants, the Commission wants to see better organisation of legal migration and also the better integration of non-EU nationals into EU society. It’s a tall order for any group of countries. In order to achieve this ambitious end, the Commission wants to ensure that all EU member states fully implement the Common European Asylum System (CEAS). It would like to reduce the incentives for irregular migration, which would involve fighting against people smuggling and increasing the effectiveness of sensible return policies in order to send some of the applicants safely home. Its rush to strike a deal with Tunisia is not without its critics, however: the Left in the European Parliament argue that Tunisia is not a safe place for its own citizens, let alone the migrants passing through. The Left argue that there is no legal basis for any sort of deal and is, in a way, a blank cheque for an undemocratic government to ignore human rights. The Commission believes the EU’s external borders should be better protected with increased funding and a more prominent rôle for the borders agency, Frontex. The Commission wants better safeguarding of the border-free internal Schengen zone, and to promote the legal migration of those with skills Europe needs. It also believes that the EU should cooperate more closely with non-EU countries in repatriating irregular migrants that fail to meet to conditions for legal entry.

Can it be done? It’s difficult to say, but it shouldn’t be impossible as long as European politicians respect the rules governing asylum and continue to make welcome those who qualify for entry. Europe needs skilled people; it doesn’t need smugglers who endanger lives to make money. If everyone followed the rules, Europe would acquire a valuable labour force with new skills. Politicians must stop viewing all migrants as dangerous criminals to be repulsed. That way, lives would be enriched and there would be no place for smugglers. Sadly, that looks very unlikely to happen.