© Wikicommons / LaserGuided

MULTIPLICATION CAUSES DIVISION – Europe’s population trends are worrying planners

Population growth is something we have taken for granted in Europe, but if you look closely, it’s a very uneven pattern and seems to be on the decline. Spanish women, who give birth to 1.26 children on average, seem to be among Europe’s least fertile. This contrasts with women in France who are among Europe’s most fecund with an average 1.84 children. The late British physicist, Stephen Hawking, once predicted our planet’s doom if its population continues to double every forty years. “By the year 2600, the world’s population would be standing shoulder to shoulder,” he said, “and the electricity consumption would make the Earth glow red-hot.” Don’t worry, it won’t. Hawking was not only a brilliant physicist, he was also a gifted self-publicist (always in a good cause) and he was looking for support for a project to send a fleet of small robotic spacecraft, using the power of light to fill their sails, towards the Alpha Centauri system, more than four light years away.

Obviously, despite the sails giving the vessels a great velocity, no craft can reach, let along exceed, light speed, so the trip could take up to 30 years. It’s an interesting idea, but it doesn’t really solve the problems of a planet running out of resources to feed a population standing too close together to move. Strictly speaking, it was very much a shared project, its other notable supporters being the Israeli-Russian venture capitalist Yuri Milner and Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg. Incidentally, a signal beamed from the fleet on arrival at Alpha Centauri would take another 4 years or so to get back and it would probably simply report that the planet, Proxima Centauri b, is uninhabitable.

Population growth is a heated topic of debate. Environmentalists are afraid that we will outgrow our planet and denude it of vegetation and other life forms (probably not viruses, but no-one cares much about them) unless we restrain ourselves and start producing fewer children. Population figures alone hide another fact: our global population is not only growing, it’s growing older. I mentioned the difference in birth rates between Spain and France, but these are merely a reflection of an odd fact that has become clear over the last three decades: fertility rates are relatively high in Northern Europe and low in the South. Few people believe this difference is biological; it is more likely to be the result of family care policies and financial realities. Providing care services is expensive, and in 2015 in the South, the investment in them represented around 1.5% of total GDP, while Northern Europe invests 3.5%, more than twice the proportion. The lower figure must discourage people from having large families (which is expensive) and encourage partners to go on working to earn more money; more easily done with only a small family to consider. Interestingly, the statistics do not bear this out. It’s in countries that pay out the most in care services and where the highest proportion of women are in the jobs market that the birth rate is highest.

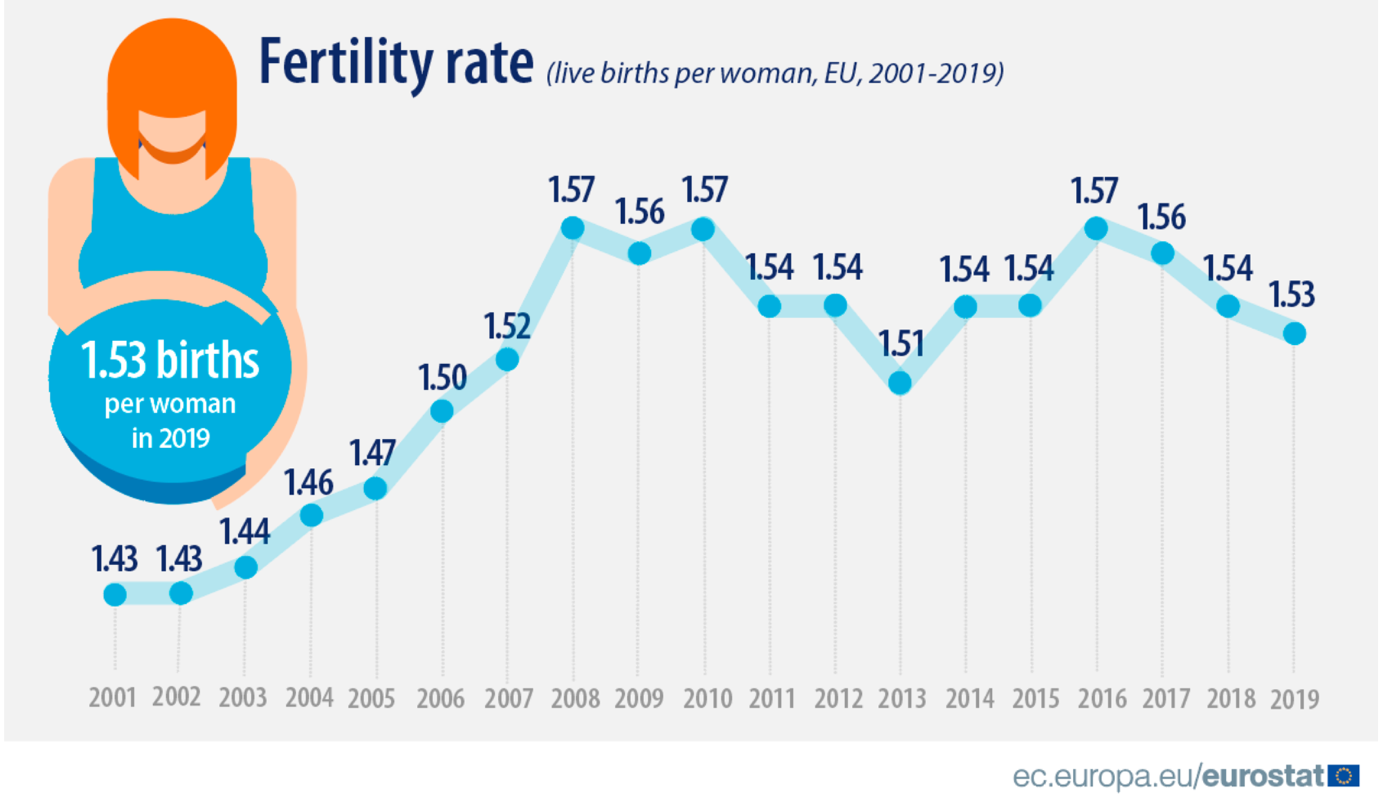

The birth rate in Europe, as in other parts of the world, varies over time. It peaked in Europe at the start of the 1960s – in 1964, it peaked at 6.797-million births – and has declined since, reaching a low of 4.365-million in 2002. There was a brief resurgence after that before a further decline to just 4.167-million in 2019. Another noticeable trend has been for women to give birth to their first child at an increasingly older age. There has been a tendency to put off a first pregnancy until a woman is more mature. In the United States, the average age for a woman in her first pregnancy is 26.8, and that is lower than the average in OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) countries. In the years from 1970 to 2017, the average age for women giving birth for the first time rose by up to five years. Adolescent fertility rates have fallen sharply, too.

Across the OECD as a whole, an average of 11.8 births have been recorded per one thousand women aged between 15 and 19, although in Chile, the current adolescent fertility rate stands at 44.7 births per one thousand women aged 15 to 19 and a significant 66.2 births per thousand in Mexico – more than 5 times the OECD average.

The National Bureau for Economic Research (NBER) attributes the fall in birth rate to personal choices, rather than any possible biological cause. “Several factors are thought to be driving that decline in Western Europe,” says its website “Socioeconomic incentives to delay childbearing; a decline in the desired number of children; and institutional factors, such as labour market rigidities, lack of childcare, and changing gender roles.” It all sounds very reasonable. People do not feel the pressure of their 19th century predecessors, where large families were essential because of high infant mortality rates. But it’s a change that comes at a cost to society. In a report for the NBER, it is noted that: “In the short term, low fertility rates raise per capita income by lowering families’ costs of child-rearing and boosting the share of working-age people.

GROWING OLD DISGRACEFULLY

But as that working-age population moves into retirement, the number of workers who replace them will shrink. So, whatever short-term boon European nations may have gained from low youth dependency will be overwhelmed eventually by the economic burdens of old-age dependency. It’s a point that is noted by the European Commission in a 2018 report on ageing: “The old-age dependency ratio (people aged 65 and above relative to those aged 15 to 64) in the EU is projected to increase by 21.6 percentage points, from 29.6% in 2016 to 51.2% in 2070. This implies that the EU would go from having 3.3 working-age people for every person aged over 65 years to only two working-age persons.”

That clearly has cost implications for member states. Across the EU as a whole, the total cost of an ageing population looks daunting, according to European Commission estimates. Spending on such things as pensions, health care, long-term care, education and unemployment benefits is expected to go up by 1.7% to 26.7% of GDP between 2016 and 2070. According to the OECD, “much of the decline in fertility among women aged 20-29 occurred between 1970 and 1995, but in many countries fertility rates for women in their twenties have continued to fall since 1995.” It is a matter of some concern for the European Commission and one for which no-one has yet come up with a viable solution. “Long-term care and health care costs are expected to contribute the most to the rise in age-related spending,” reads a Commission report, “increasing by 2.1 percentage points. Public spending on pensions is expected to rise…until 2040 before returning close to current levels by 2070. Education expenditure is projected to remain unchanged by 2070. Unemployment benefit expenditure is projected to decline by 0.2 percentage points.”

Japan, which has the fastest-ageing population, raised the issue at the 2019 G20 meeting, which it hosted. The global advisory and digital services provider, ICF, set out some of the major issues arising from it. “In the European Union, the working-age population—between 15 and 65—is projected to fall from 333 million in 2016 to 292 million in 2070,” it points out. “Meanwhile, the share of people aged 65 and over will rise from 19% to 29% of the population, and people aged 80 and over will increase from 5% to 13%.” Naturally, older people are going to want to enjoy a well-earned retirement, funded by the pension scheme to which they have contributed throughout their working lives. But that pension fund is not a bottomless pit of gold; it seems as if the actuaries got their sums wrong. With more people having to dig into it, without it growing proportionately bigger, the pit of gold will turn out to be fairy gold, end-of-the-rainbow gold, but the sense of entitlement will, understandably of course, remain. In his video series, “Biology: The Science of Life”, Dr. Stephen Nowicki, Bass Fellow and Professor of Biology at Duke University, put forward the notion that populations of any species can reach what he called a “carrying capacity”, which he defined as “the maximum size a population should be able to achieve given the amount of resources available in the environment in which it lives.”

Prior to the pandemic, Europe’s workforce had been becoming more mobile, crossing borders in pursuit of work and a better life. As a result, many women have been giving birth in a country that is not their own. The share of children born to foreign-born mothers differs significantly among EU Member States: in 2019, more than 65 % of the children born in Luxembourg were from foreign-born mothers, while in Cyprus, Austria and Belgium this share was around one third. I have fond memories of Luxembourg, mainly from covering so many EU (or EEC before that) Council meetings. Luxembourgers are understandably proud of their tiny country and get annoyed when people idly assume they can talk to them in French or German (they can, of course, but that’s not the point), so to ensure I got prompt service in the press bar at the Council building, I learned those vital words: “Zwee Béier, wann ech gelift” (two beers, please), which almost always won me good service and a smile from the barmaids. According to the Britannica website, “Luxembourgish is a Moselle-Franconian dialect of the West Middle German group” and it has lots of French, German and Flemish words mixed into it, too. Luxembourgish policemen attending road accidents that involve foreign-registered cars and drivers have been known, I was told by a Belgian friend, to pretend it’s the only language they can speak. But I digress.

TWO’S COMPANY, THREE’S A SOLUTION

The birth rate has been a topic of much discussion in China, whose ‘one-child’ policy led to a shrinking but also ageing population. After appeals to limit family size, which had not worked properly, the Chinese government instituted a “one-child” policy in 1980, in a bid to limit the country’s burgeoning numbers. As a result, the fertility rate declined to lower than two children per woman in the min-1990s. Because male children could inherit the family name and property, there was an increase in the numbers of female foetuses aborted, leading to a society in which there was a disproportionately high number of males. Female babies brought to term were often put up for adoption and many ended up in the United States and other Western countries. Other children, brought to term unofficially because their parents resisted abortion, ended up facing hardship without the documents they would need, so in late 2015, Beijing announced that the policy was to be discontinued. From early 2016, families would be allowed two children, but this failed to raise the birth rate as predicted. Faced with low birth rates, an ageing population, and a dwindling workforce, in 2021 the Chinese government raised the limit to three children.

Worldwide, the SARS-CoV-2 virus has rendered most population planning out of date and unhelpful. In one generation from now the world looks like being unrecognisable, in population terms. Before it started, mass migration was seen as the factor most likely to impact on population numbers. A report drawn up for the European Commission in 2019 pointed out how westward migration over the preceding quarter century had affected smaller, poorer nations. For example, Bulgaria and the Baltic States lost between 16% and 26% of their people in that 25-year period. “Intra-EU mobility has the potential to produce large population shifts within the EU over time,” it reported. “If the movements of recent years persist as they have, the population of Romania would reduce from 19.9-million in 2015 to 13.8-million by 2060 (that is a worrying number, representing around 30% of the population). Conversely, the losses would be less than half (only around -14%) without intra-EU mobility.” The Member States on the receiving end of these flows have come to rely on them to help compensate for their own ageing or shrinking populations, but the effect on their total populations is more limited because they are generally more heavily populated in the first place.

As the report points out: “Differences in wages and living standards continue to drive westward migration within the EU. Targeting economic inequality between Member States can encourage greater cohesion and integration and can help those Member States facing disproportionate population decline, a loss of working-age population, brain drain and more pronounced population ageing.” Of course, it tends to be the young, able, educated, and clever who seek their fortunes in a new land, so it becomes not only a drain of able labour but a brain-drain. The poor countries are losing the very people they are going to need most in the future. And by 2060, the OECD predicts, 32% of Europe’s expected population of 521-million will by over 65, which means that a small and probably shrinking actual workforce will be trying to help support a large and growing section of society: the elderly, certainly, but also the sick and those with small children needing care.

So, for Europe, as for the rest of the world, the future was already looking difficult and plagued with problems that nobody has really found workable ways to overcome. These problems are especially noticeable in economically advanced states, such as Japan. Japan may be economically wealthy but it is often used as an example of a nation struggling with an ageing – even an aged – population, coupled with a reduction in adults of working age. In Europe, though, there are countries struggling with very much the same problems but lacking Japan’s relative wealth. Bulgaria, for instance, comes fifth in the European table of countries with an old and ageing population, but it lacks the financial wherewithal to address the problem. Politically, they cannot attract greater immigration, so instead they seek to attract the Bulgarian diaspora from neighbouring countries to come home. Fiscally, the effects can be severe. One million Bulgarians have left their home country to seek their fortunes elsewhere since the fall of the Soviet Union.

ALL CHANGE

And then along came a virus that can mutate faster than scientists can find new ways to destroy it or at least to keep it in check. Slightly more than two thirds of the global population have experienced some form of lockdown during the pandemic, with an all-too predictable increase in domestic abuse and violence and a marked decrease in women’s access to medical and prenatal services. Lockdowns are also known to have impacted on social circumstances and mental health, while the accessibility of condoms has become more difficult for many women. The United Nations predicted that this fact alone could lead to 116-million unwanted babies.

According to Frontiers in Public Health, an open-access website, fertility rates tend to respond to poverty; those without jobs or prospects are likely to postpone having a child. This is especially the case in Low-to-Middle-Income Countries (LMICs), such as India or Pakistan. There is also the possibility of the virus directly and physically affecting the fertility of the population; as Frontiers in Public Health explains, “SARS-CoV-2 binds to the Angiotensin Converting Enzyme-2 (ACE-2) receptors to enter the cells of the human body. Several hypotheses have pointed the presence of ACE-2 receptors on male Leydig cells and female ovaries as the possible thread to directly affect human fertility.” So far there has been no evidence that this is the case, we are told, but it is something that we should, perhaps, bear in mind.

Otherwise, though, there’s no doubt that the pandemic will affect the birth rate in rich places like Europe and the United States, as well as in LMICs. According to the PMC website, representing the US National Library of Medicine and the National Institutes of Health, “There was no correlation between the monthly number of Covid deaths and the monthly number of perinatal deaths (r = 0.465, NS), preterm births (r = 0.339, NS) or hypertensive pregnancies (r = 0.48, NS). Compared to the combined numbers for the same month in 2018 and 2019, there were no significant changes in perinatal deaths or preterm births in the months when Covid deaths were at their height.

The rate of preterm birth was significantly less common in January-July 2020 compared to January-July in 2018/2019 (7.4 % v 8.6 %.” It had been predicted that with couples being forced to spend more time together, births would increase, as well as domestic violence, but that hasn’t been the experience (except for the domestic violence, sadly). The Economist reports that in the 21 countries that published their population data for January, the first month in which babies conceived at the height of the “first wave” of the pandemic were due, births were down by 11% per thousand people, and down by 12% based on the countries’ fertility trend during the decade leading to 2019. Perhaps sex is losing its appeal.

Certainly, those who’ve been asked have mainly said they plan to start a family later because of the pandemic. Given the way the virus keeps coming back in new forms and varieties, it could be much later. We are currently experiencing the Delta variant; how long before the Epsilon version puts in an appearance? An on-line article by the Rand Corporation, published in April 2021, predicts fewer births in the months ahead. “While national data of U.S. fertility during the pandemic are not yet available, some states have released preliminary information,” says the report. “Philip Cohen, a sociologist at the University of Maryland, College Park, has been documenting some of these findings. He finds a drop in the birth rate between five and ten percent across several U.S. states. California, for example, saw a ten percent drop in birth rates in December 2020 compared with December 2019. Preliminary data on Spain shows a 23 percent drop in birth rate between the December/January period of 2020–2021 compared to the prior year, suggesting that birth rate declines may be even greater in other countries.” A number of reports have focused on how the pandemic has affected childcare duties, but it has also affected care systems for older people, with some families taking on the care of elderly relatives to keep them out of care homes where infection rates have soared tragically. It is hard to predict if this “home caring” trend will outlast the pandemic; probably not, or not for long. Most young (or youngish) families don’t want their “old fogey” relatives cluttering up their lives. And to be honest, the “old fogeys” probably wouldn’t enjoy it much, either.

JOIN MY CLUB. OR USE MY CLUB

Migration, though, continues. As the Rand Corporation report points out: “Worldwide, more people than ever before live in a country other than the one in which they were born. This reached 272 million in 2019, an increase of 51 million since 2010. Currently, international migrants make up 3.5 percent of the global population.” Politically, of course, migration is a tricky subject, even though the worldwide spread of homo sapiens depended on it. We know our ancestors first evolved in Africa, but into a variety of forms. By one million years ago, some hominid species had started to migrate towards the north and east, learning how to use language and how to control fire, it’s thought. Between 70,000 and 100,000 years ago, our own ancestors, homo sapiens, also left Africa, probably crossing the Strait of Hormuz. With so much of the world’s oceans bound up in ice, it would have been a short and fairly easy crossing. Some headed east, some west, and by 40,000 years ago, they had reached Western Europe, Asia by 50,000 to 55,000 years ago and Australia soon afterwards. It took them rather longer to reach the Americas. They were, in many cases, following in the footsteps of Homo Habilis, Homo Erectus, the Neandertals, the Denisovans and perhaps others now lost to history or to archaeological discovery.

Experts in the United States are still arguing over how and when the first indigenous peoples got there. It’s assumed by many that they crossed the land bridge of Beringia, which joined Siberia with Alaska while the seas were bound up in ice. They were prevented from travelling further by the Cordilleran Ice Sheet, which covered up to 2.5-million square kilometres of North America. A growing number of scientists, however, now believe that native peoples arrived earlier and, in some cases, by boat. There are even some, admittedly a minority, who believe that the Cerutti mastodon site in San Diego County, California, shows evidence of butchered mastodon bones and stone tools from 130,000 years ago. According to Scientific American, Steven Holen of San Diego Natural History Museum, together with his colleagues, has concluded that the bone damage is clear evidence of butchering. If that proves to be the case, the butchers could not have been homo sapiens and presumably would have been homo erectus. The outcome of these arguments is important for native Americans, who will know more about their ancestors and whether or not they had settled in Beringia before the melting ice flooded it as well as destroying the ice barrier that had blocked further migration southwards. It will be less important for the vast majority of Americans who are descended from European migrants, of course. In any case, migration played a major part in the growth of the United States. It was in 1932 that Edgar B. Howard discovered butchered mammoth bones at a site at Clovis in New Mexico, together with slender stone spear tips that became known as Clovis points, thought to be evidence of the ‘first Americans’ and dating from 13,500 years ago. There is evidence to link the Clovis culture with the older Diuktai culture of Siberia. However, older remains than the Clovis points, it’s believed, have been found in Chile and elsewhere. Human populations have always moved from place to place; it’s part of what makes us human. Ultimately, our mitochondrial DNA may prove something that a great many scientists believe, namely that all of us today are descended from one woman, sometimes referred to as mitochondrial Eve. Given the immense damage we have done and are still doing to the planet, she has a lot to answer for, poor woman. And from a biological standpoint, her mate must surely share the blame.

Meanwhile, ongoing migration continues to divide opinion and embarrass politicians. Italy’s highly capable new prime minister, Mario Draghi, has persuaded other EU leaders to listen to his attempts to get a discussion going on migration. Italy complains that it is affected disproportionately by refugees travelling north from Africa and that the EU’s current rules on redistributing them don’t work. Other leaders, though, seem loath even to discuss the issue. When it was brought up at a recent summit, leaders spent little more than 5 minutes talking about it, which led to Draghi being criticised by his right-wing, anti-immigrant opponents at home.

Even Social Democrat-led Denmark has recently passed a law under which asylum applications will be looked at in countries outside the EU and even outside Europe. Since then, border guards from the EU’s Frontex agency have been sent to Lithuania to help deal with the influx of would-be refugees from Belarus fleeing the brutal regime of President Alexander Lukashenko.

The President of the European Parliament, David Sassoli, posted a Tweet about the issue: “Once again someone is unacceptably playing with people’s lives. It’s clear that across Europe, be it in the South or East, we need a common asylum and migration system to respond to the crisis.” There’s no doubt that Mario Draghi would agree, at least. With migration, tempers flare and all too often people die. Al Jazeera reported an incident that took place at the start of July. “A non-profit sea rescue group (Sea Watch International) has slammed Libya’s coastguard,” said the article, “after it witnessed the Libyan maritime authorities in what it described as chasing a crowded migrant boat and shooting in its direction in an apparent effort to stop it from crossing the Mediterranean Sea to Europe.” A spokesperson for Sea Watch, Felix Weiss, said that after shooting at the migrant boat, the Libyan coastguard vessel tried to ram it, presumably to sink it. “Those who shoot at refugees and try to capsize their boats are not there to save them,” he said. “The EU must immediately end cooperation with the so-called Libyan Coast Guard.”

Europe may well need migrants. Its population is not growing as fast as it used to and may soon go into reverse. The Economic Policy Committee and the European Commission predicted in 2006 that the working age population in the EU will decrease by 48 million, a reduction of 16%, between 2010 and 2050, while the elderly population will increase by 58 million, which equates to 77%. A recent report for the European Parliament showed a high rate of intra-EU migration, as people from Central and Eastern Europe move to the wealthier West to improve their lives.

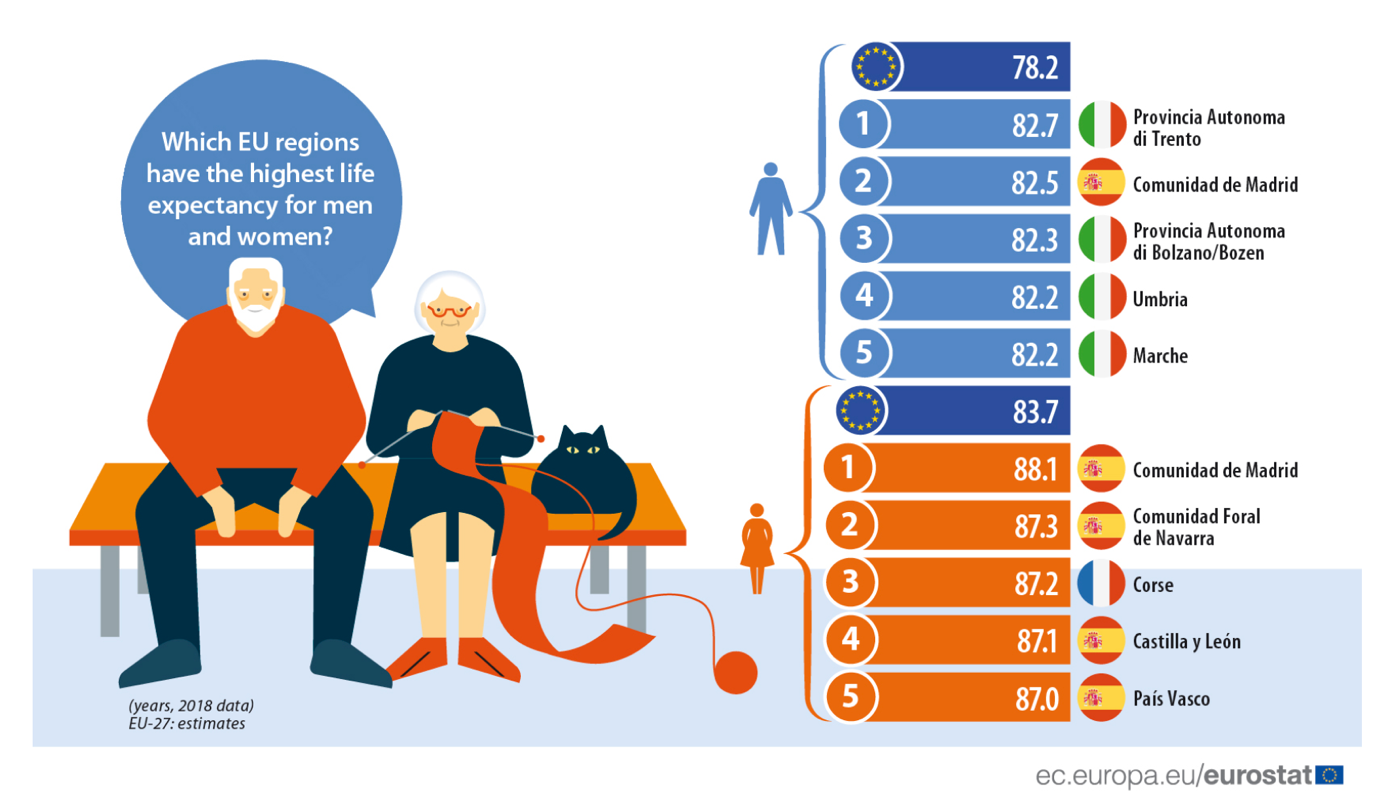

The report also pointed out that Europe has an ageing population. Because of increasing life expectancy, 30.3% of the population is projected to be aged 65 years or older by 2070, compared to 20.3% in 2019. It’s well known why the population growth has slowed to a standstill: in most OECD countries, the average age at which women first give birth now stands at 30 or above. It could lead to a skills shortage in wealthier countries and immigration could help to solve the problem. Of course, it’s not just the politicians who have to be persuaded. They obviously want to keep their jobs, which means retaining the support of the voting public, and opinion polls suggest that the majority of people are opposed to immigration, especially if the immigrants choose to set up home in their neighbourhoods. In many countries, the decline in fertility for women in their twenties mainly occurred between 1970 and 1995, although in some places it has continued and fertility rates have actually risen slightly among women aged between 30 and 39. In fact, fertility rates overall have been in steady decline since the mid-1960s. There was a brief hiatus around the year 2000 but by 2010 the decline had resumed. In 2019, there were 9.3 births per 1,000 women. In the year 2000 it had been 10.5, in 1985 it was 12.8 and back in 1970, an impressive 16.4.

Perhaps it’s just that people are more serious and career-focussed than they were back in the era of flower power and hippies. There are signs that people are less inclined to get close to strangers these days, emotionally as well as physically, so they are more naturally cautious. There is an old saying: familiarity breeds contempt; over-familiarity simply breeds.