Visit any public place in the West, especially in places popular with tourists, and you’ll see lots of people taking “selfies” – photographs of themselves, with or without their friends or colleagues. Often they have “selfie sticks” that allow their smartphones to be far enough away to allow a photograph that isn’t just a distorted and over-large nose with a face dropping away in perspective around it. It’s a trend I’ve never understood: yes, I take photographs of places I visit, but I don’t want my face or body blocking the view. I already know what I look like, thank you very much; I see myself in the mirror when I shave or comb my hair. I don’t want to see myself grinning against an attractive scene when the attractive scene will be all the more attractive if I’m not in it. But then, I’ve never understood why people take photographs of restaurant meals. Food is for eating, in my book, not for gazing at or showing to social media ‘friends’ you’ve never actually met.

But if these inexplicable trends seem strange to those of us brought up in the age of the Brownie box camera, mechanical typewriters and large Bakelite telephones attached by cloth-covered cables, then the spread of surveillance cameras is a bit of a shock. Yes, I know they help the police to catch thieves, but they do seem reminiscent of the sort of dystopian world George Orwell described in his book, 1984. You may like to take pictures of yourself but how many are being taken by official bodies or the police without you realising? Or by your neighbours, for that matter? In Britain, the use of closed-circuit video cameras (CCTV) is growing fast but it is regulated by the General Data Protection Regulation and the Data Protection Act (DPA). In simple terms, you can set up cameras that capture anything on your own property but not beyond it. No spying on your neighbours’ garden or yard, for instance, however annoying (or suspicious) they may be. No invading people’s privacy or filming where people might assume they’re entitled to privacy. In the United States, it’s legal to record surveillance video with a hidden camera inside your home without the consent of the person being recorded but in most states (not all) it’s illegal to use a hidden camera where the subjects ‘have a reasonable expectation of privacy’. So no aiming through your neighbours’ bedroom window, either.

Protection Supervisor (EDPS)

You will not be surprised to learn that a number of EU institutions use surveillance cameras to enhance their security, but they have to follow certain rules. In the words of the European Data Protection Supervisor’s own website “Video-surveillance footage often contains images of people. As this information can be used to identify these people either directly or indirectly (i.e. combined with other pieces of information), it qualifies as personal data (also known as personal information).” The EDPS says staff and visitors must be kept informed and that the use of CCTV must be controlled. For instance, “cameras can and should be used intelligently and should only target specifically identified security problems thus minimising the gathering of irrelevant footage.” Furthermore, the retention of recorded material is time-limited, says the EDPS: “Although the installation of cameras might be justified for security purposes, the timely and automatic deletion of footage is essential. The EDPS requires all EU institutions to have clear policies regarding the use of video surveillance on their premises including on potential storage.” It doesn’t actually set a time limit, you may have noticed.

PROGRESS – OR IS IT?

Technology moves on, of course. Now, surveillance cameras can also identify the people being filmed, or most of them; some of them, anyway. Face recognition technology allows for people in crowds to be identified by computer algorithms that take a vast number of measurements of the faces recorded: width of mouth, distance to chin and across cheeks, width of eyes, height of forehead and so on. It will undoubtedly help the police and security services. Except that it doesn’t always work.

According to Australia’s Human Rights Commissioner, Edward Santow, facial recognition software is less reliable when used on people of African or Aboriginal Australian ethnicity. It can also be deceived by anyone wishing deliberately to do so. A group calling themselves the Dazzle Club have found that by applying make-up to their faces to create similar sorts of asymmetric camouflage to that used on warships in the First World War, cameras could not identify them. You can see an example of this type of camouflage on HMS Belfast, moored in the River Thames. She is painted in what the Imperial War Museum describes as “Admiralty Pattern Disruptive Camouflage”, and very smart she looks, too, even if you would probably not want to paint your face in a similar way. The startling patterns make the wearers stand out from any crowd but they are virtually invisible to artificial intelligence, which, of course, is not very intelligent. One of the founding fathers of AI, Yoshua Bengio, told the science magazine New Scientist he has no fear of AI taking over our lives any time soon: “AIs are really dumb. They don’t understand the world. They don’t understand humans. They don’t even have the intelligence of a 6-month-old.” It’s reassuring to note how much the part they play in our lives is growing, isn’t it? Bengio does note, though, that the only real danger lies in AI getting into dangerous hands. “It isn’t that the AI is malevolent, it is the humans that are stupid and/or greedy.” But I guess we knew that.

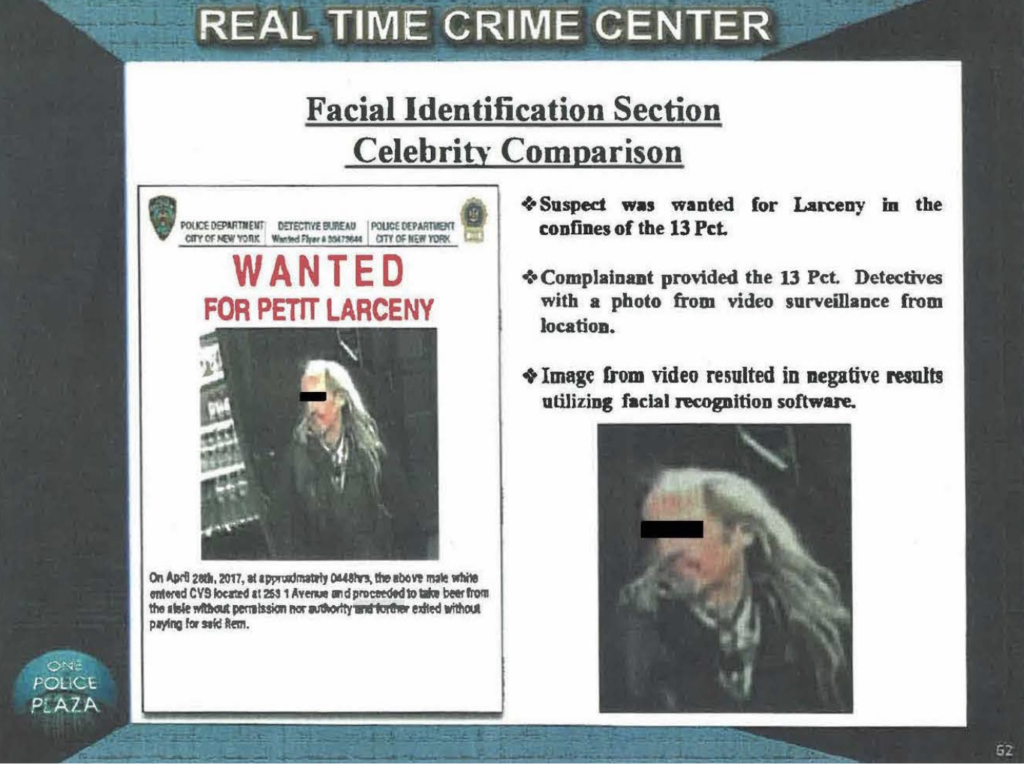

the NYPD used an image of

Woody Harrelson facial

recognition to arrest

There are two main concerns about face recognition technology: its accuracy (or perceived lack of it) and its misuse. That is a big problem in China, where some 300 tourist sites use facial recognition to admit visitors. People running the sites argue that it can shorten queues, which is dubious; a season ticket holder at a Chinese safari park sued it to get a refund over the issue. But many office workers in Beijing’s financial district are subjected to facial recognition to check in and out, too. The government in Beijing is not keen to discuss facial recognition or its proliferation and especially not its widespread use of the technology to keep an eye on millions of Uighurs in the western region of Xinjiang. There is a growing concern, even among Chinese officials, that the poor protection of personal data could hamper the expansion of Chinese technology firms. Some people may be surprised to learn that under China’s consumer protection laws, consumers must give their consent before their personal information can be collected and stored, and there are fears that the widespread use of facial recognition ignores that law.

Commissioner at the Australian

Human Rights Commission

The European Union introduced the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in May, 2018, bringing in new obligations and requirements where the processing of personal data is concerned. The GDPR has a very wide definition of personal data, covering any information relating to an identified or potentially identifiable person. In other words, any data that identifies an individual or which can be combined with other data to identify an individual counts as ‘personal data’. According to EU rules, much facial recognition data will also be sensitive data to which stricter rules apply. Biometric data for the purpose of uniquely identifying someone, and data revealing racial or ethnic origin, fall into this category. Processing this kind of data is prohibited within the EU unless specific conditions are met. The EU has been considering a 5-year ban on facial recognition in public spaces until the risks it presents are better understood and legal protection is put in place, although this idea looks set to be scrapped. The technology itself is progressing too fast for a 5-year ban to work. The idea, however, has been causing dissent among the big tech companies, with Google largely in favour of the ban and Microsoft against. Microsoft’s chief legal officer, Brad Smith, is adamant however that development must continue in order to overcome its shortcomings. One of those shortcomings, presumably, is that it is being used not only by law enforcement agencies but also by private enterprises that could misuse it. Although the EU ban seems unlikely to go ahead at the time of writing, the Fundamental Rights Agency of the European Union (FRA) has published a paper recognizing that “given the novelty of the technology as well as the lack of experience and detailed studies on the impact of facial recognition technologies, multiple aspects are key to consider before deploying such a system in real-life applications” The Govinfosecurity website quotes a French scientist, Félicien Vallet, a privacy technologist at CNIL (Commission Nationale de l’Informatique et des Libertés), France’s data protection authority, “Focusing on one particular identification method gives a very skewed picture of the nature of surveillance we as a society are subjected to,” he says.

the Massachusetts Institute of

Technology’s Media Lab

© Wikicommons

“At CNIL, we are not in favour of government using facial recognition anywhere and everywhere. However, we understand that the technology has its pros, and hence we are not looking at a complete ban on this. It certainly depends on the application of facial recognition.” Germany has announced that it is dropping plans to deploy facial recognition systems at 134 German railway stations and 14 airports. Last year, the U.S. cities of San Francisco and San Diego banned the use of facial recognition software by law enforcement in public places. And many U.S. Democratic presidential candidates support at least a partial ban on the technology.

DRAWBACKS IN COLOUR

Undoubtedly its use has helped solve – or even prevent – certain crimes, but others see it as an infringement of civil liberties and a potential risk because the algorithms used can be subject to bias. For instance, racial bias. “These errors are not evenly distributed across the community,” Edward Santow, Australia’s Human Rights Commissioner, told the ABC network, “So, in particular, if you happen to have darker skin, that facial recognition technology is much, much less accurate.” Darker-skinned women are especially prone to error, according to research by Joy Buolamwini, a computer scientist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Media Lab, quoted by ABC’s Fact Check. They had an error rate of 35% in one test. The problem is that facial recognition systems have to rely on machine-learning algorithms that are trained on sample sets of data, so if dark-skinned people are under-represented in the data sets, the system will have problems identifying black faces.

But the ABC Fact Check also found other problem groups for facial recognition: not only black people but also all females and all people aged between 18 and 30. The concern over data bias and inaccuracy has recently led to Australia’s Parliamentary Joint Committee on Intelligence and Security calling for the Identity-matching Services Bill to be amended to improve privacy protection and safeguards against misuse. Even so, people in Australia are not being warned when facial recognition technology (FRT) is in use, unlike those in London and South Wales in the UK, where warning notices are deployed. In Australia, it has been admitted that FRT is being used in petrol stations and supermarkets to judge the mood of the customer so that targeted advertising can make use of their displayed emotions. Systems that can identify emotions have been developed by Affectiva/iMotions, Microsoft and Amazon, but there may be other companies conducting similar research. Those who favour unbridled capitalism that uses every available technique to part customers from their money may think that’s a good idea. Those who believe in civil liberties may not.

Surveillance is in widespread use in Israel, especially in Tel Aviv where it’s claimed that the installation of surveillance cameras comes in response to public demand. The Municipality claim that use of the cameras has helped solve 520 crimes between January 2018 and September last year. The police have to apply to the Municipality to view it within thirty days of the incident they want to see, otherwise it is automatically erased. But Tel Aviv’s cameras do not have facial recognition capabilities and senior officials say the idea is not even being considered at present, according to Haaretz Israel News

YOU LOOKING AT ME, PAL?

It’s easy to understand why police forces are interested in using the technology. It has been trialled in parts of London and across the United Kingdom since 2016 but has come in for criticism over the high instances of false positives, incorrectly flagging up innocent passers-by as known criminals. It has been used at London’s famous Notting Hill Carnival and at the Remembrance Day services in 2017. Despite the continuing problems, the Metropolitan Police say they will roll out Live Facial Recognition (LFR) to see if it helps them to catch serious criminals. The special cameras will be set up, the force says, in areas they consider they are most likely to spot people on known ‘watch lists’ of criminals wanted for serious or violent offences. However, the cameras will be clearly marked, while foot patrol officers nearby will hand out leaflets explaining what the cameras are and how they are being used. In a statement, the force said: “Every day, our police officers are briefed about suspects they should look out for; LFR improves the effectiveness of this tactic.”

On the Metropolitan Police website, the system is explained and defended: “The Met currently uses NEC’s NeoFace Live Facial Recognition technology to take images and compare them to images of people on the watchlist. It measures the structure of each face, including distance between eyes, nose, mouth and jaw to create a facial template. Where it finds a match it sends an alert to officers on the scene. An officer then compares the camera image to the person they see and decides whether to speak to the person or not.” The system will only keep images that have generated an alert, and only for up to 31 days unless an arrest is made, in which case it is retained until any investigation or judicial process is concluded. The biometric data of those who don’t cause an alert is automatically and immediately deleted.” Anyone seeing the warning notices about LFR may fear that deliberately walking away and avoiding the cameras could arouse suspicion, but the Police say not. “Anyone can decide not to walk past the LFR system; it’s not an offence or considered ‘obstruction’ to avoid it,” the force website proclaims.

make, model, color and license plate reader

© Wikicommons

Elsewhere in the UK, Police in South Wales have adopted the same technology. Assistant Chief Constable Richard Lewis explained in a statement: “This facial recognition technology will enable us to search, scan and monitor images and video of suspects against offender databases, leading to the faster and more accurate identification of persons of interest.” The technology is being deployed at Cardiff Airport and at major Welsh sports stadia, where the police hope it will help them prevent violence by identifying known trouble-makers. “The technology can also enhance our existing CCTV network in the future by extracting faces in real time and instantaneously matching them against a watch list of individuals, including missing people,” says Lewis, “We are very cognisant of concerns about privacy and we are building in checks and balances into our methodology to reassure the public that the approach we take is justified and proportionate.” South Wales Police and Crime Commissioner, Alun Michael, said: “Our approach to policing is very much centred upon early intervention and prompt, positive action.” He accepts that the deployment will not be welcomed by civil liberties groups. “The introduction of a system such as this will invariably raise certain questions around privacy and whilst I appreciate these concerns, I am reassured by the protocols and processes that have been established by the Chief Constable and operational colleagues to ensure the integrity and legitimacy of its use.”

In Russia, there is growing concern over the use of FRT at public gatherings and rallies, threatening the anonymity of those attending. According to Planet Biometrics, “Tverskoy District Court of Moscow is hearing a complaint submitted by the civil rights activist Alyona Popova and the politician Vladimir Milov, who argue that data collection about participants at lawful public gatherings results in the violation of their right to freedom of peaceful assembly.” Popova and Milov are asking the court to “prohibit the use of facial recognition technology at rallies and to delete all stored personal data already collected.”

So far, Russian judges have been less than sympathetic to the complaints. Last November, the Savelovsky District Court of Moscow refused to examine Popova’s claims that her right to privacy were undermined by the establishment of Moscow’s video surveillance system. It’s very different from the claimed adhesion to civil liberty norms of the UK police. Natalia Zviagina, Amnesty International’s Director in Russia, is very worried. She says the use of face recognition technology is “deeply intrusive” and should not be used by her country’s security forces. “In the hands of Russia’s already very abusive authorities, and in the total absence of transparency and accountability for such systems, it is a tool which is likely to take reprisals against peaceful protest to an entirely new level,” she says. “It is telling that the Russian government has provided no explanation as to how it will ensure the right to privacy and other human rights, nor has it addressed the need for public oversight of such powerful technologies.” She fears that the way the authorities responded to peaceful protests last year has already shown that the technology will be used for profiling and surveillance of the government’s critics. “The deployment of facial recognition systems during public assemblies – which all available evidence suggests is its primary purpose – will inevitably have a chilling effect on protesters.” Interestingly, in Russia, Roskomsvoboda, a Russian non-governmental organization that supports open self-regulatory networks and protection of digital rights of Internet users, launched a campaign calling for a moratorium on government mass use of face recognition until the technology’s effects are studied and the government adopts legal safeguards that protect sensitive data. My advice would be: don’t hold your breath on that one.

recognition glassesvip

@people.cn

CHINA’S WATCHFULNESS

However, the widest and seemingly most indiscriminate use of FRT has been in China. This may not come as much of a surprise: China is not famed for its belief in civil liberties. To prevent illegal subletting, for instance, many housing developments have facial-recognition systems that allow entry only to residents and certain delivery staff, according to state news agency Xinhua, which writes of Beijing that “Each of the city’s 59 public housing sites is due to have the technology by year’s end.” Chinese start-up company Megvii touts the use of its facial recognition software in public housing security schemes as a selling point for future investors. It’s probably quite a sensible line to take; the Chinese government wants to see its companies as world leaders in AI. The on-line journal Wired quotes Freedom House, a US-government-backed non-profit organisation, which warned in a report last October that “Chinese surveillance deals also export the country’s attitudes to privacy and could encourage companies and governments to collect and expose sensitive data. It argues that companies and products built to serve government agencies unconcerned about privacy are unlikely to become trustworthy defenders of human rights elsewhere, and can be forced to serve Chinese government interests.” This could, of course, be a kind of re-run of the sort of anti-Huawei hysteria that gripped the United States, whose government wants no rivals to its own high-tech companies. On the other hand, a commercial approach based on the attitudes of its government (and maybe biggest customer) could easily be perceived as an acceptable norm, the breaching of which would be unimportant.

According to Wired, Megvii says “it has raised more than US$1.3-billion (€1.18-billion), primarily from Chinese investment funds and companies, including e-commerce giant Alibaba. One of China’s state-owned VC funds also has a stake and a seat on the start-up’s board. Other backers include US-based venture firm GGV and the sovereign wealth funds of Abu Dhabi and Kuwait.” Certainly, the arrival and application of face recognition technology has helped the company to grow. Together with its AI rivals SenseTime, CloudWalk and Yitu, it has made facial recognition commonplace in China.

The police routinely scan concert crowds for suspects, pulling people from the throng. There are even Google Glass-type devices that police officers can wear to scan whoever is in front of them. Citizens can even pay in shops and pay their taxes by showing their faces to the camera. The New York Times reported that Megvii, SenseTime and CloudWalk had developed software to identify Uighur faces but Megvii’s PR spokespeople deny that the software can be used to target particular racial types. Even so, the company’s FRT has been used as part of the enormous security apparatus set up to watch over the Xinjiang region, where some one million Uighur Muslims have been interned in so-called “re-education” camps.

Despite having a research laboratory not far from Microsoft on the outskirts of Seattle, Megvii accepts it’s unlikely to sell much of its technology in the United States. Ironically, the outbreak of corona virus infections is adversely affecting face recognition because so many people are now wearing face masks. Many mobile phones in China are unlocked by face recognition and some users are now asking Apple and others to reintroduce fingerprint identification. The face masks only come off when the wearers are in bed. The wearing of masks for protection against the corona virus is also complicating things at railway stations, hotels, airports and shops that employ face recognition. The technology giant Huawei tried to come up with a way for it to work despite a mask but took the decision that it simply wasn’t possible.

BEING WATCHED

The use of facial recognition technology has led to much concern by civil liberties organisations such as Liberty. On its website it calls for FRT to be banned as an unacceptable intrusion. “The cameras scan everyone in sight – adults and children – snatching our deeply personal biometric data without our consent. This is a gross violation of our privacy.” Liberty says the fear of constant supervision could cause people to change their behaviour (which may, of course, be the intention). “We may choose not to express our views in public or risk going to a peaceful protest. We shouldn’t have to change how we live our lives to protect ourselves from unwarranted surveillance. In short, facial recognition tech makes us less free.” That’s not all; Liberty thinks it plays into the area of racism, despite the fact that the technology is not very good at identifying people with darker skin.

“Disproportionate surveillance is most keenly felt by people of colour – the Met used facial recognition at Notting Hill Carnival for two years running, and twice in the London Borough of Newham, one of the UK’s most ethnically diverse areas.” It would be interesting to know how successful the operation proved, given the known drawbacks.

Similar concerns have been raised by the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU): “The biggest danger is that this technology will be used for general, suspicionless surveillance systems. State motor vehicles agencies possess high-quality photographs of most citizens that are a natural source for face recognition programs and could easily be combined with public surveillance or other cameras in the construction of a comprehensive system of identification and tracking.” The ACLU, having failed to get answers to a freedom of information request about how widely-used the biometric technology is, has now taken to the courts: “Separate lawsuits have been filed by the ACLU and its Massachusetts branch against the US Department of Justice, the FBI and the Drug Enforcement Agency in the US District Court for the District of Massachusetts,” says Engineering and Technology Magazine.

The UK campaign group Big Brother Watch (citing George Orwell again, of course) is even more outspoken in its condemnation of facial recognition technology. Its Director, Dr. Silkie Carlo, wrote about the group’s objections in TIME magazine: “The U.K. is certainly adopting surveillance technologies in a style more typical of China than of the West. For centuries, the U.K. and U.S. have entrenched protections for citizens from arbitrary state interference – we expect the state to identify itself to us, not us to them. We expect state agencies to show a warrant if our privacy is to be invaded. But with live facial recognition, these standards are being surreptitiously occluded under the banner of technological ‘innovation’.” She has condemned the deployment of the technology at five London locations by the Metropolitan Police and told the Law Society Gazette that the decision “flies in the face of the independent review showing the Met’s use of facial recognition was likely unlawful, risked harming public rights and was 81% inaccurate”. In October last year, more than 90 civil liberties NGOs gathered in Albania at the International Conference of Data Protection and Privacy Commissioners. They called for a global moratorium on the use of the technology.

Meanwhile, facial recognition systems can be bought on-line, should you wish to spot people whilst serious upsetting any number of civil liberties campaigners. It would seem that, whatever the law may say, now or in the future, the technology is here and readily available. All you need is money, a database and somewhere to mount your camera. You can recognise people who come to call, as long as you restrict your camera to looking only at people on your property. Of course, you could always just open the door and ask them; the Brownie box camera technique, perhaps, but more reliable than software that’s often wrong and which doesn’t work at all during a virus scare. As Yoshua Bengio said (quoted earlier in this article) AI isn’t really very bright. With its use being mainly harnessed by security teams and those trying to sell you things, many of its users may not be very bright, either. But nothing is going to stop the onslaught of facial recognition and AI, now that it has been invented. As Shakespeare put it in Hamlet:

“Why, let the stricken deer go weep,

The hart ungallèd play;

For some must watch, while some must sleep:

So runs the world away.”

The questions many are asking are: exactly who must watch? And what do they do with whatever it is they see? And should some of us, like the world in Shakespeare’s example, run away, just in case?

Robin Crow

Click here to read the 2020 March edition of Europe Diplomatic Magazine