© Fishmongers.org.uk

I was raised on Tyneside in North East England, in the fine old (if somewhat scruffy and soot-covered) town of Jarrow. The soot (and what we called ‘smuts’ – the effluent from a plant producing coke for fuel) – came mainly from the coke works behind my parents’ house, turning coal into coke day by day for those with a boiler to fuel but also for the steelworks down the road. A vital industry it was, but it was a dirty one for anybody living close to it, leaving smuts on any washing my mother hung out in the back yard. Mind you, the coke plant itself was impressive. It could be a stirring sight on a dark winter’s evening, a blaze of seemingly infernal light glowing hot and devilish against the smoky cloudscape, as if Satan and his infernal legions had taken up residence there. But there was more to being raised on Tyneside, even if the people living on either side of the river didn’t really mix with each other very much. Just across the River Tyne, on the northern shore was North Shields, with its fish quay, where local people could go to buy the best parts of that day’s catch.

Jarrow was a mining and engineering town, complete with its own coal mine and steel rolling mill, but the area was heavily dependent on the fishing industry, too, and had been since mediaeval times, even though most of the the fishing was based on the Tyne’s northern bank. That had given rise to a whole folk culture and to a great many folk songs, too, such as “When the Boat Comes In”, in which a grandfather is trying to distract his grandson from his hunger by talking of a future in which they will be wealthier. It’s written in North Eastern (Geordie) dialect:

“Dance ti’ thy daddy, sing ti’ thy mammy,

Dance ti’ thy daddy, ti’ thy mammy sing;

Thou shall hev a fishy on a little dishy,

Thou shall hev a fishy when the boat comes in.”

(In more normal English: “Dance for your father, sing to your mother, dance for your father, to your mother sing. You will get a small fish on a small dish when the boat comes in.) The boat “coming in” really means when they somehow live to see better times and perhaps make a bit of money.

My upbringing gave me a fondness for my old home turf – I still have a sister and brother-in-law living there – although I’ve lived in many other places since leaving Tyneside, from various parts of Britain to a spell in fascinating and historic Brussels. But back to North East England: on the River Tyne’s northern side, in around 1225, the Prior of Tynemouth Priory, Germanus, built some very basic homes for the starving families of the poor living there and eking out an existence of sorts from fishing. They were just huts, known as “shielings”, but they provided shelter for very poor families. Eventually, his action would be copied on the other side of the river, creating another town (or village, rather) and the two became the north shielings and the south shielings, now known (and for many, many years) as North Shields and South Shields. Coming from south of the river, I knew South Shields rather better when I was a teenager, being a closer (and thus cheaper) option for a night out with friends than posher Newcastle, but North Shields was more important to the fishing industry and, apparently, it still is. I recall the smell of fish in the air when I rode my bicycle through those streets with their fishy debris, which I often did on my way to explore further up the coast. Of course, it developed over the years. Better houses, better shops, several chapels (the fisher-folk were mainly low-church in their religious choices and seemingly quite devout), and, of course, places of entertainment and hostelries for the passing trade, like the Northumberland Arms. It was built in 1806 as part of the New Quay development, providing space for markets and fairs and the town’s first deep-water quay. It also provided what was, at its opening, a first-rate hotel, the Northumberland Arms, which later gained worldwide fame and notoriety as ‘The Jungle’, the sort of drinking establishment that sensible people avoided. I was asked about it once by an Indian man who was a sailor and was going out with a distant cousin at that time, somewhere in the rural south of England. The Jungle’s fame had spread far and wide.

SHIVER ME TIMBERS

During all the wrangling about the government’s proposals to quit the European Union, the issue of fishing and fisheries was subjected to a determined (if not always truthful) campaign by the Anti-EU and heavily Eurosceptic UK Independence Party and the right wing of the increasingly right-leaning Conservative Party.

They were not alone. The British government was equally keen to rid itself of the Common Fisheries Policy, which right-wing Conservatives saw as a concession of British rights over our coastal waters to “foreigners” (they never came to terms with seeing our friendly continental near neighbours as anything other than “foreigners”, despite our shared history, and therefore irredeemably viewed them as “evil” in some way). The campaign used very nationalist (all Britons good, all foreigners bad) memes.

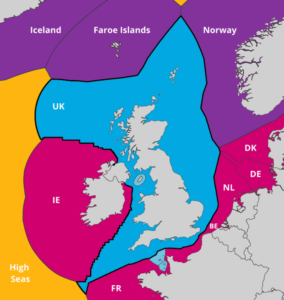

The European Union’s fishing policy was based upon granting fair and equal access to Europe’s fishing waters for all member states. It came into force in 1983 as part of the European Community’s agricultural policy. Under this agreement EU nations no longer control their own territorial waters or set their own quotas for catching fish. Instead, fish are classified as a “common resource” (if you asked them I suspect that is how they would see themselves) and the rules governing fishing quotas, catch levels, subsidies, discards and a whole range of other measures are set centrally by the European Commission. Although the individual EU member states are still responsible for policing their waters and enforcing the regulations, all EU countries with a coastline and a fishing industry were to share their territorial waters (the Exclusive Economic Zone – or EEZ – as it was called) with each other, and all would have the right to fish in each other’s waters, with the EU setting the catch levels for each country in each specific area.

The UK’s more nationalist politicians found this state of affairs with regard to Europe distasteful and seemed to develop a “Captain Pugwash” complex, (Captain Pugwash was a rather silly cartoon pirate in a children’s television programme) setting their sails and priming their canon while they sharpened their cutlasses for the fray, no doubt crying “Avast there, landlubbers!” or “Yo, Ho, Ho and a bottle of rum!” under their breaths). Obviously, this is an overstatement, but to hear comments from such members of Parliament as arch-Brexiteer Jacob Rees-Mogg you’d be excused for thinking that. When asked by the HuffPost UK website if Brexit had been worthwhile in monetary terms, the Minister for “Brexit Opportunities and Efficiency” (that is Rees-Mogg’s title, seriously) accepted that financial savings were hard to spot (although he told the London radio channel LBC that there could perhaps be “very slight” (and undefined) savings on cheeses and fish fingers) that: “I’ve always thought it’s all about democracy. Can you change your government, can you make decisions about how you are governed?” It seems not; at least, it has proved impossible to get rid of a prime minister who has lost much of his public support. Rees-Mogg thinks it’s worse in the EU: “That is the big and overwhelming advantage of Brexit, and then you come to the debate as to whether democracy also makes you more prosperous and I think it does and there’s a great deal of evidence for that.” He failed to show any, however, when asked. It seems to be closer these days to shouting “shiver me timbers”, “splice the mainbrace!” or “cleave him to the brisket”. No, I don’t know what they all mean (the last one is apparently an especially nasty thing to do with a cutlass to someone tied to a mast in an upright posture) but the phrases rightfully and more accurately belong to the 17th and 18th centuries anyway and may never have been carried out in real life. At least, I sincerely hope not. Certainly such behaviour played no part in the daily lives of the fishermen who sailed from the Tyne in the hope of returning with fish to sell, or at least returning alive.

The North Sea is a tempestuous place at the best of times. There are many tales of disaster there, few more tragic than the capsizing and sinking of a London and Aberdeen passenger steamer, the Stanley. It, and a schooner called the Friendship, also carrying passengers, together with a brigg (name not recorded) became stuck on the Midden Bank rocks, according to the local records of Thomas Fordyce, written on 24 November, 1864. With a heavy sea running, it was impossible for a lifeboat to reach the vessels, which gradually capsized and sank close enough to shore for the locals to watch in mounting horror. Those travellers were not the first to suffer such a fate. The “Black Middens”, as they’re known, are hidden at anything less than a very high tide, and they’re extremely deadly. In three days of blizzards in 1864, the Middens claimed 32 passengers and two lifeboat men, all within sight of shore. Fishing in the North Sea was never a job for softies. Local lifeboats were launched but none of them could get close enough to the stricken Stanley, nor the passenger schooner Friendship, due to the high seas. The fact that the disaster was played out so close to land and in full view of the people watching from the shore, caused horror and outrage. A public meeting was called afterwards, following which the Tynemouth Volunteer Life Brigade (TVLB) was formed, the oldest organisation of its kind in the world. It was a very good development, but a very heavy price had been paid for its creation. The TVLB has gone on to save many lives.

PROMISES, PROMISES

If only Brexit had worked out quite so well for those making a living from the sea by the harvesting of its fish. Fishing contributes around £1-billion (€1.16-billion) to Britain’s GDP, which means that in economic terms it’s a relatively unimportant industry. However, with the UK being an island nation, any activity related to nautical matters assumes an importance well above its monetary value. Many British people will happily witter on about how “vital” our fishing industry is and how bold our fishermen, even if most members of the British public eat less fish these days than their parents and considerably less than their grandparents used to consume.

The fishing industry was given a lot of promises about their post-Brexit future. Without the Common Fisheries Policy (CFP), voters were assured, the UK would have complete control of British waters and, of course, a bigger share of catches made in UK waters. They would no longer be bound by the hated CFP, either, allowing Britain to set up its own, conservation-based fishery management system. Brexit gives the UK control over its 200-nautical mile (370-kilometre) Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), recognised under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). In fact, given the geographical facts of life, the EEZ fails to stretch to 200 nautical miles: across the Irish Sea, the English Channel and the southern North Sea, it soon runs into the EEZs of other countries, equally determined to defend their fish stocks. Several of them have historic claims to access, although the UK is not legally obliged to honour them under UNCLOS, it would be expected to in most cases. As Aaron Hatcher of the University of Portsmouth wrote in a report: “The UK is not obliged to grant access to its EEZ, although under UNCLOS it would be expected that it would. The UK is also not obliged to grant access to all the EU boats which currently fish in UK waters, but the UK EEZ forms such a large part of Europe’s seas that catches from the UK zone are of very considerable economic importance to a number of EU member states.” Hatcher points out that Denmark, for example, “would find it impossible to catch its quotas of herring and mackerel if it could no longer fish in UK waters, with devastating consequences for its industry.” Its fish-eating population would be rather annoyed, too.

Let’s just take a look at the types of fish the North Shields boats go after. There’s brill, for instance, not to mention brown crab and cod, dab, Dover sole and gurnard. Or how about haddock, hake, and halibut? Or lemon sole, ling and mackerel? Monkfish, place and pollack are there, too, along with squid, turbot and whiting, plus wild salmon and something called witch. No spells, no cauldrons and no flying broomsticks; witch is just a strange-looking flatfish that has both its eyes on its right-hand side of its head, which means its appearance is extremely odd. It’s unlikely to win a beauty contest and this has undoubtedly dented its popularity. It has seldom featured on anyone’s “favourite fish” list. Perhaps that’s why it was “re-branded” as “Torbay sole”. But it’s the North Sea’s shellfish that come first anyway. Nephthrops norwegicus, also known as Norway lobsters or Dublin Bay prawns, live in burrows in muddy sea-beds, the surrounding sediments being normally 20 to 30 centimetres beneath the surface and surrounded mainly by silt and clay. The burrows they build are more-or-less permanent and vary little in design, being usually 50 to 80 centimetres from front entrance to rear. Norway lobsters spend most of their time either lying inside their burrows, apparently relaxing (do shellfish dream?) or near the entrance. They normally only leave their shelters to forage or to mate. A little like some of the humans back on shore, really, if North Shields is still much as I remember it.

Nephthrops make up a large proportion of the catch for North Shields boats. According to research carried out by Newcastle University, the fishery has seen long-term decline in employment, with the numbers involved dropping by some 36% between 1996 and 2002, although that is for the whole of England and Wales, not just the Northeast coast. Over the same time period, the fishing fleet of more than 10-million vessels fell by the same proportion. According to the report, expectations regarding further declines in fishing employment and vessels in the light of forthcoming European Council decisions on TACs (Total Allowable Catches), effort limitations and stock recovery plans and the persistently poor economic state of key fisheries; the European Commission’s upper estimate of job losses due to forthcoming recovery measures amounts to 28,000 EU jobs, even taking a very optimistic view of stock and economic scenarios. All in all, it’s not a pretty picture for the future prospects of fishing in the North Sea, nor for the fishermen who rely upon the fishing industry for their livelihoods.

PRAWN FREE

Apart from the declining earnings and the dwindling profitability of several key fleet segments, particularly within the whitefish sector, when taken together with decreasing profits for crew, skippers and owners, fishing has less of an appeal. Despite a suggestion of possible improvements in the nephthrops sector, there remains the problem of recruiting adequate crews, especially among young people, largely because pay in the sector is generally poor and work conditions are hard, dangerous and unattractive, despite much of the region’s sky-high unemployment. Who wants to be battling to keep their feet on the tossing and slippery deck of a small vessel being buffeted in a force 10 gale off the Black Middens rocks, just to haul a few shellfish out of the sea, when they could be working in an office or a factory somewhere, or merely receiving unemployment benefit? It may seem boring but it’s unlikely to kill you. Work conditions are not appealing, which, taken together with a greater concentration in the processing industry and an increasing reliance on overland deliveries, makes the industry unappealing and unrewarding, as well as dangerous.

Overall British trends have been echoed within the Northeast, with 66 vessels being decommissioned between 1993 and 1996 alone, representing a 33% reduction in fleet capacity, the highest rate in England. From an overall fleet strength of some 10-million vessels nationwide, numbers have progressively declined from 159 in the Northeast in 1994 to 76 in 2002 – a drop of 52%. The number of people employed in the industry has also (inevitably) declined, from 944 in 1995 to just 623 in 2002. That’s a drop of 34%. The number of vessels for which North Shields was the home port is down by 17, the biggest drop recorded in any of the Northeast fishing ports, although the picture is by no means rosy for any of the others, either. Perhaps Britain’s traditional love of fish and chips is being overtaken by a taste for burgers, pizzas or Kentucky fried chicken (or its imitators), or at least fewer snacks to be gobbled out in the street? However, it’s clear that there is still a demand for scampi, which is how nephthrops are usually served. I must admit that asking for “scampi-in-a-basket” sounds better than “nephthrops-in-a-basket”.

According to the North Shields Fish Quay (NSFQ) company, “North Shields is the busiest and most important fishing port on the East Coast of England.” On its website, NSFQ makes clear that “The vibrant fishing industry is still going strong on the Quay and remains the core character and uniqueness, which draws people and businesses to the area on a daily basis.” In my youth, I recall going to a friend’s house for Sunday tea, and if I was lucky my friend’s mother had been to the fish quay, crossing the Tyne aboard the Hebburn passenger ferry, and brought back the freshest fish anyone could buy at the time.

Certainly, Britain’s departure from the EU has not made things easier for the UK’s fishing industry, according to the All Party Parliamentary Group on Fisheries. “One Producer Organisation found that: ‘Obtaining equipment for vessels has been challenging due to administrative burdens of customs and the cost of duty,” while another respondent had experienced “system failures with software/labels required to export post-Brexit”. One fishermen’s association highlighted that Brexit had for them resulted in “an increase in the need for representation from the fishing industry in meetings with government and the media, all on a much-reduced budget”. Similar impacts were felt by respondents of various backgrounds, the report continued. “A pot fisherman (owner of lobster pots) said he was ‘having to throw at least 90% of the catch back’, because while demand still existed, his former buyers were dissuaded by the onerous paperwork required and the extra export costs, compared to buying similar products from Ireland.” A respondent from the shellfish aquaculture industry faced similar difficulties, reporting that “we were sending between 50 and 100 tons of large oysters to Europe every year at an average price of €1,500 per ton, but we have not sent a single oyster to the EU since January 2020, resulting in lost sales amounting to £300,000 (€347,470) since 2020.” In another example quoted in the report, a small fishmonger found that “our sales to one customer in Belgium made up around 35% of total sales, pre-Brexit, but that has now fallen to less than 5%”. The picture across the whole of the UK is much the same. Why buy from a non-EU Britain, with all that extra paperwork and taxes and duty payments when Ireland is there and still an active EU member? It’s much easier to get your Dublin Bay prawns when they actually come from Dublin Bay.

HIDDEN IN THE SMALL PRINT, (OR IN THE SMALLER THINKING)?

Bureaucracy is never popular and seldom very profitable, either. According to a report from the London School of Economics (LSE) published in 2020: “The fishing industry has been promised a lot from Brexit: exclusive control over UK waters, with tightly restricted access for EU boats; bigger shares of the catch quotas for a number of fish stocks, more in line with their actual abundance around the UK; and an end to burdensome and inflexible regulation under the Common Fisheries Policy (CFP).” It looks very promising. That is, until you look at the detail, as an London School of Economics (LSE) researcher, Aaron Hatcher, has done. “The fishing industry has been promised a lot from Brexit:” he wrote. “Exclusive control over UK waters, with tightly restricted access for EU boats; bigger shares of the catch quotas for a number of fish stocks, more in line with their actual abundance around the UK; and an end to burdensome and inflexible regulation under the Common Fisheries Policy (CFP).” It all sounds wonderful. There is a “but”, of course, despite what look at first glance like many advantages. “It will have control of its own 200-mile Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), with rights and responsibilities internationally recognised under the UN’s Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).

The UK can indeed then decide who has access to its waters. Of course, the UK’s geographical position means that its EEZ extends to a lot less than 200 nautical miles in most places, in particular, in the southern North Sea and Channel and in the Irish Sea, where the UK’s own EEZ meets the EEZs of other countries.” All OK so far? Hmmm… “Nevertheless, the UK EEZ does represent a significant part of the area in which other EU member states are accustomed to fish. It is also worth recalling that the UK has never actually had exclusive control over its own 200-mile EEZ.

When the UK joined the EEC in 1973 its fishery limits only extended out to 12 miles, and some other European countries already had historical fishing rights in the 6-to-12 mile zone (rights that were written into the UK’s accession treaty, and subsequently into the CFP). Beyond 12 miles were international waters, open to all. It was only in the late 1970s that the EEC Member States, acting in concert, extended their EEZs out to 200 miles, forming a de facto European fishing “pond” to which equal access had already been enshrined in the very first of the CFP regulations. As a result of this, other EU Member States have strong historical claims to fishing rights within the UK’s EEZ. The UK is not obliged to grant access to its EEZ, although under UNCLOS it would be expected that it would.

The plain fact is, despite all those tales of the British loving their “fish ‘n’ chips”, that British people don’t actually consume very much fish (and seem to have gone off the more traditional type of chips, wrapped in newspaper, too). British appetites have been won over by largely US-based tastes in fast-foods, such as beefburgers or what the Americans call pizza, (which generally bears little resemblance to the somewhat tastier stuff that is served up in Italy) and other popular fast foods. “What really matters to UK fishermen is access to markets,” says Hatcher’s excellent and concise report. “UK consumers eat relatively little fish compared to consumers elsewhere in Europe, and what they do eat is largely supplied by non-EU imports (think canned tuna, tropical prawns, Norwegian/Icelandic cod and frozen blocks of Alaskan pollack).

Most of the UK’s high value catch is exported, the great majority to the EU. Tariff-free trade in fish with the EU is therefore vital for the UK fishing industry.” And that, of course, is precisely what the UK government signed away when Britain left the EU. Dividing up the access to the various bit of sea is a complicated business about which there is often a bit of squabbling and Britain’s departure from the EU is unlikely to have much effect upon it, other than to postpone some of the squabbling until the media have become involved. Then it comes down to vicious slanging matches between right-wing “we-hate-all-foreigners and couldn’t give a toss about accuracy or fairness” newspapers and more liberal “let’s-be-kind-and-generous-to-everyone” left wing and centrist journals. In any case, zonal attachment to certain fish varieties (and yes, of course I know that nephthrops are not, technically speaking, fish) and their preponderance within a given EEZ seem likely to become lost in the wrangling still to come. “Ironically, by leaving the EU,” Hatcher warns, “the UK might lose access to the flexibility that is built into the system – the facility for international quota swaps – which UK fishery managers currently use extensively in support of the industry.”

“Don’t give a child a fish but show him how to fish,” said Mao Zedong (allegedly). Perhaps we should adapt the aphorism to make it more appropriate for negotiations about fishing rights. How about: “Don’t tell countries who can fish where and how much they can catch; tell them how best to argue about it afterwards for a few months or years.” Come back five years later and ask if they’ve managed to agree anything. They are most likely to still be arguing. Fishermen’s leaders were said to have been “jubilant” about leaving the EU but is seems as if the euphoria was short-lived. Fish (and nephthrops) are not very nationalistic and patriotic creatures; they really don’t care whose flags are flying from the masts of the vessels out to catch them.

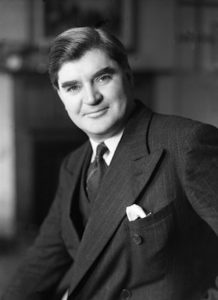

Why should they care if they’re only going to be eaten anyway? “This island is made mainly of coal and surrounded by fish,” wrote British post-war Labour politician Aneurin (“Nye”) Bevan. “Only an organizing genius could produce a shortage of coal and fish at the same time.” I suppose that’s what happens when the boat goes out, or at least fails to “come in”. Bevan, who had worked as a low-paid coal miner from the age of 13, believed essential services, including health, should be free at the point of delivery. After holding the post for two months he resigned because the new Labour government announced the start of charging for eyesight and dental prescriptions. What he would have made of the current impasse over fisheries is anybody’s guess.

As for the Northeast coast’s remaining fishermen, it seems to be a case of making their demands known in high places. As the old Geordie saying goes, “shy bairns get nowt” (shy children don’t get anything). Whether that makes any impression on a government apparently convinced that Brexit has made things better for our fishermen and for fish markets, albeit with no evidence to back them up and quite a lot that suggests the opposite to be true, is anybody’s guess. It seems certain that it’s what they believe, anyway, so they are, at least, telling the “truth” as they see it. And of course, fish can’t “belong” to anyone. Can you imagine a sort of maritime version of Rawhide, with Clint Eastwood helping to round up the fish (and the nephthrops) so they can be “branded” in some way? All we really need to do is to stop politicising our taste in seafood and just eat what we like, wherever it comes from. It’s a great big global marketplace out there, as it should be; let’s make the most of it, while we still can.