It had been hailed as the high-flying darling of Germany’s stock exchange: a huge provider of high-tech financial services and processor of payments. Although it was seen as a blue-chip success story, suspicion had trailed Wirecard, based just outside Munich, since an investigation by Britain’s Financial Times (FT) in 2019, coupled with revelations from whistle-blowers.

The final collapse on 25 June came just seven days after the company’s long-term auditors, EY, refused to sign off the accounts for 2019 because €1.9-billion had disappeared. In a statement, EY said: “There are clear indications that this was an elaborate and sophisticated fraud involving multiple parties around the world.” Wirecard’s Austrian founder and CEO, Markus Braun, was arrested, accused by Munich prosecutors of a fraud that probably stretches back to 2015, involving inflation of the company’s worth and balance sheets to deceive investors. Wirecard’s former head of finance, Burkhard Ley, has also been arrested, along with the group’s head of accounting, Stephan von Erffa.

Another executive now in custody is Oliver Bellenhaus, who ran Wirecard’s CardSystems Middle East, from an office in Dubai. He was arrested on suspicion of conspiracy to commit fraud, attempted fraud and aiding and abetting other crimes. He had travelled from Dubai to Munich and handed himself in, but he remains in police custody because he is considered a flight risk. All of this casts doubt on Germany’s financial regulator, BaFin (Bundesanstalt für Finanzdienstleistungsaufsicht).

An international arrest warrant has also been issued for another Austrian, Jan Marsalek, the company’s former chief operating officer, who has disappeared but whose interests may well tie him to the very heart of the fraud. Some sources initially suggested he may be in the Philippines, where Wirecard has a presence and where he told colleagues he was going ‘to find the missing millions’. But the documentation for his journey seems to have been faked, possibly by officials at Manilla Airport. It now looks more likely that he is hiding out in Belarus, where it will be harder to get him back. He may have travelled on to Russia. He is believed to have been working with (but not actually for) Russia’s military intelligence unit, the GRU, which is held responsible for the attempted murders of Sergei Skripal and his daughter in the UK and for manipulating the 2016 presidential election in the United States.

He is now thought to have possible links to Russia’s secret intelligence agency, the FSB, as well and is known to be ‘of interest’ to that agency. No fewer than three western intelligence agencies have questions to put to him, quite apart from asking why a financial company executive was trying to recruit 15,000 Libyan militia troops. Marsalek was involved with the Austria-Russian Friendship Society, a Russia-backed organisation intended to improve Russo-Austrian relations.

According to the FT: “The Friendship Society, which has courted criticism in the past because of its cosy relationship with Moscow, hit the Austrian headlines this week, after it was revealed that its finance secretary had been receiving classified documents from Mr Marsalek – illegally obtained from Austria’s interior ministry and security service – and passing them to the country’s far-right populist party, the FPÖ.” Indeed, few of the people Marsalek had dealings with seem to have any idea of what his true intentions were. It’s fairly safe to say, though, that he wanted to provide military and financial aid to far right political causes and that he is deeply involved with Russian power politics. It seems possible that his militia recruits were intended to police Libya’s southern border against illegal immigration, giving him leverage in Brussels where the issue remains a major problem. But the FT reports that in that respect, Marsalek had other strings to his bow: “When it came to his plans to try to set up a southern Libyan border force, Mr Marsalek regularly told interlocutors he would have no problem securing armed force on the ground from Russia – thanks to deep relationships he held with Russian ‘security specialists’.”

Three passport photos from Marsalek’s Austrian passports © bellingcat.com

It was reported by the investigative website Bellingcat that Marsalek had made some sixty visits to Russia, initially using commercial flights but from 2016 on, in private executive jets and to a variety of Russian locations, not just Moscow. “One particular trip stands out for its party-like country-hopping nature,” reports Bellingcat. “On 29 September 2016 Marsalek flew in from Munich to Moscow at 1:55 am, only to depart for Athens at 7:58 that same morning. The next day he flew back from Greece – this time into St. Petersburg, where he stayed only 5-and-half hours, before taking off back to Greece – but this time to the vacation island of Santorini. He changed three different private jets during this whirlwind of a trip.” But his alleged links with the FSB didn’t stop the agency from refusing him the right to leave Russia in 2017. Bellingcat again reports that after a 5-day visit to Russia he was denied the right to leave. “Immigration records show that on the morning of 15 September, at 8:05 his attempt to leave the country using a private business jet was denied by FSB’s border service. It is not clear what caused the detention, but it appears that his initially booked jet had to be let go without Marsalek. At 17:35 that afternoon, Marsalek did leave Russia after all, using a different private jet.” This was the last time he visited Russia, or at least the last time he did so using his Austrian passport. What was he up to? That’s something Wirecard’s shareholders and the police and financial authorities in Germany, Austria and Brussels would love to know. In any case, these are not the activities of your average company financial controller. When Wirecard went down, it owed its creditors almost €3.5-billion.

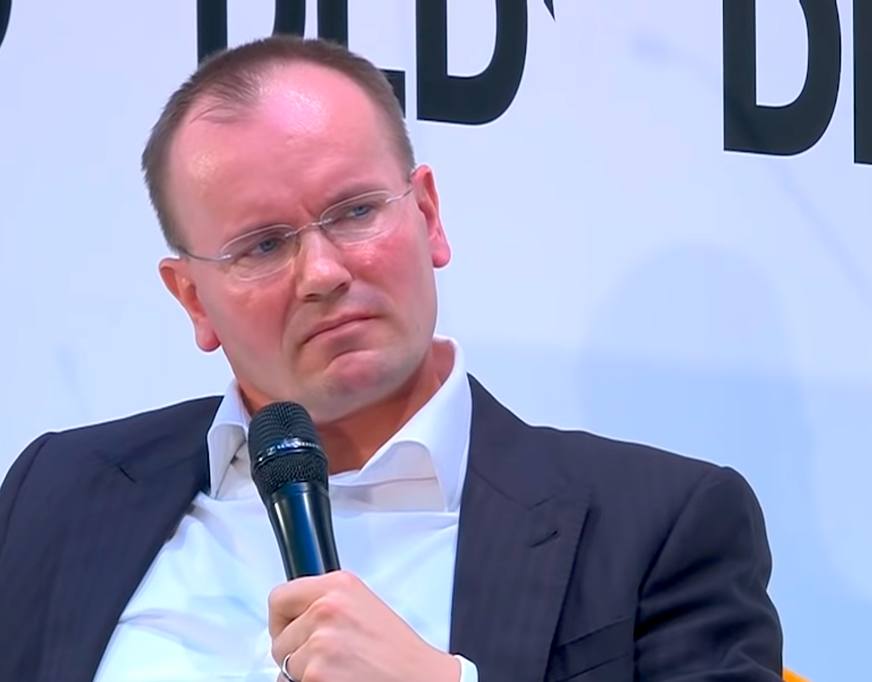

Markus Braun © Techcast.com

The collapse forced out Chief Executive Markus Braun who admitted that €1.8-billion of its book money simply didn’t exist. That’s a lot to lose down the back of the sofa. For now, at least, Marsalek is wanted by the authorities in Germany and Austria on charges of fraud and embezzlement. Instead of a simple embezzlement and fraud investigation, though, it begins to read like the plot of a novel by John le Carré. Marsalek is known to have had three separate Austrian passports, although one of them bore an unofficial number, as well as a passport issued by another unnamed country and a diplomatic passport, again issued by an unidentified third country. The FSB started to monitor his movements, which is unusual, according to Bellingcat. “We have previously seen global monitoring of foreigners in this database only in one other case – that of a financial backer of the UK Brexit referendum in 2016.” Russia is also refusing to cooperate with a Europol request for help in finding Marsalek.

WATCHING, WAITING, FIDDLING

But it’s an ill wind that blows nobody any good: a number of hedge funds have been shorting Wirecard’s stock for some time and it’s now believed that at least ten of them have made a killing on the collapse.

Wirecard promotion © wirecard.com

The hedge fund with the biggest short position, Coatue Management, is thought to have made a paper profit of €271-million, according to calculations by Reuters. While Wirecard’s shares crashed from €104.5 to €2.5 in less than a week, a fall of 97%, the ten known hedge funds made millions, and many more may have made considerable gains as well. In fact, according to Market Watch, “Short sellers, who borrow shares and sell them hoping to buy them back for less in the future, notched paper profits of $2.6 billion (€2.22-billion) off Wirecard’s plunge, according to data-analytics firm S3 Partners. Bets by the eight funds with the biggest short exposure to Wirecard, including in options markets, delivered paper profits of $1 billion (€0.85-billion) according to Breakout Point, a research service.” A bonanza day for those who believed the prophets of doom. In fact, those prophets turned into profits. Schadenfreude for fun and profit, indeed. However, as Bloomberg points out in an on-line opinion, short sellers also serve a useful purpose. Yes, they make a profit, “But, believe it or not, for many short sellers it’s not only about the money. They perform an important though rarely acknowledged function in rooting out corporate malfeasance through countless hours of detective work, often at great expense. As with Wirecard, they’re sometimes happy to share their concerns with regulators.” One short seller, Fahmi Quadir of Safkhet Capital, which had taken a short position on Wirecard stock, wrote to the German regulator, BaFin, to draw attention to the problem when BaFin took the bizarre step of banning short selling of Wirecard stock for a period of two months in order to uphold market confidence. Meanwhile, a social media campaign was launched against short sellers. Wirecard’s board always denied they were involved, but short sellers were subjected to Internet trolls and phishing attacks and one man claims his house was put under surveillance by unidentified men. It makes one wonder if the management were quite so ignorant of Wirecard’s illicit shortcomings as they later claimed; they were very determined to protect the fortunes they had built on fake foundations. Wirecard admitted that they had hired private investigators in the past.

Various funds had been betting against Wirecard for years, which was one reason why the elusive Marsalek travelled to London in 2018, carrying a dossier of files apparently from the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons, OPCW. One of them gave details of the plot to kill Sergei Skripal, another contained the chemical formula for Novichok, the world’s deadliest nerve agent and the one used in Salisbury, UK, in the unsuccessful murder attempt that none-the-less killed an innocent woman and seriously injured several other people. The OPCW is known for its tight security, but the FT reports that an attempt to hack into its files had been made by Russia’s GRU. The attack was uncovered by Dutch intelligence services in October 2018. Had Marsalek’s Russian friends provided the data? And if so, why? Was it just to prove that Marsalek is not a fantasist and that nobody should touch Wirecard? Vladimir Putin’s Russia, however, seems willing to leave its fingerprints on brazen outrages around the world that it later denies; there’s no proof that could stand up in court but more than mere suspicion that Moscow wants everyone to know that it can exert its influence on the world stage without being nervous about discovery. It’s the sort of thing that keeps Russia’s restless (and often extremely wealthy) emigrés on their toes, aware of the fact that although they’re abroad, they’re never out of the Kremlin’s reach.

Wirecard claims that the €1.9-billion disappeared from its operation in the Philippines, which was run by Marsalek. The money vanished from escrow accounts and Wirecard said it had been the victim of fraud, before admitting the money had never existed. An escrow account is normally used to hold funds in trust while two or more parties complete a transaction, after which the funds are dispersed to the appropriate parties. The difference here is that the supposed escrow accounts didn’t actually exist. Banks in the Philippines said the documents produced by Wirecard appeared to be false. The country’s central bank said the supposed money had never entered its financial system. The money that is missing leaves a number of lenders facing the probability that they will never be repaid, including Germany’s Commerzbank and LBBW as well as the Dutch lenders ABN Amro and ING. It’s an irony for Commerzbank, because its position on the blue-chip index was lost when Wirecard was admitted to it. For Germany, where the rise and rise of Wirecard was hailed as a German success story, it’s hugely embarrassing.

BaFinHeadquarters in Bonn© Wikipedia

The whole affair turns a timely spotlight on the country’s oversight procedures. It’s especially embarrassing for Germany’s financial regulator, BaFin, which in 2018 seems to have played down negative reports in the media, especially an investigation by the Financial Times suggesting that Wirecard executives were cooking the books, just as some whistle-blowers were claiming. Instead of looking into the truth of the claims, BaFin banned investors from shorting their stock, while that stock fell in value by more than 40%. Interestingly, BaFin still believes it reacted correctly, although a German MP, Florian Toncar, of the Free Democratic Party, said in an interview on Norddeutscher Rundfunk radio that “This is a documented failure of supervision to intervene when there was clear evidence in this case.” It’s an especially damaging blow because Wirecard was regarded as an innovative company. “Wirecard was until now,” said Toncar, “one of the few functioning tech companies that have come up with new ideas in the marketplace and now it turns out that that was to a great extent smoke and mirrors.”

THE FINGER OF BLAME

It’s not the first time that a German company has been caught out in dishonest acts, even though the country’s policy of co-management (known in Germany as Mitbestimmung) ensures that workers have a place on boards and therefore the right to scrutinise what the company is doing. Ever since 1951, it’s been the law that large firms, initially in the coal and steel sectors, reserve half the board seats, together with voting rights, for members of the workforce, most often elected by the workers themselves from union slates. This meant that workers could vote on all the firm’s strategic choices and have access to all the same documents as management and shareholders. In 1952, another law made it mandatory for large firms in other sectors to reserve a third of the seats on the board for representatives of the workforce. These laws were further enhanced in 1969 and 1982 while a law on co-management was enacted in 1976, that requires firms with more than 2,000 employees to save half their seats on the board, together with voting rights, for worker representatives, or in the case of firms with between 500 and 2,000 workers, one third of the seats. These laws have been used to explain Germany’s success as an industrial power, although it didn’t stop unlawful practices: just look at Volkswagen and the diesel emissions scandal. And Germany is still making fairly slow progress at improving board oversight, getting more women onto company boards and trying to get companies to include financial experts among its board appointees.

Wirecard headquarters in Munich

In the case of Wirecard, it’s the parent company, Wirecard AG, that has filed for insolvency. It employed only about 200 people, although in the wider group there were some 5,800 employees, most of whom seem to have been happy at the company. Marcus Braun had an 81% approval rating among staff. It’s worth remembering that Wirecard is more than Wirecard AG. According to the eFinancial Careers website, “Wirecard Bank, which processes credit card payments, is not part of the insolvency proceedings and the UK’s Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) has said that Wirecard’s U.K. business can continue operating, issuing e-money and providing payment services.” The FCA has imposed a number of requirements on Wirecard, however, including that it must not dispose of any assets or funds, and not carry out any regulated activities. It is authorised to issue e-money and provide payment services but must also say on its website that it is no longer permitted to conduct any regulated activity. June salaries for employees in Germany, France and Luxembourg are said to have been suspended. But it may not be the end of the Wirecard story. It’s not clear what happens next in the U.S.,” writes eFinancial Careers, “where Wirecard was on a hiring drive and just brought in a senior ‘talent acquisition partner’ based in Pennsylvania to oversee the expansion.” However, Wirecard still has a recruiting website, on which it says “As an international employer with locations on all continents, we offer you a host of opportunities to further your personal and professional growth. Our outstanding pioneering spirit and highly motivated employees make Wirecard a truly unique company to work for.” Well, yes, but it’s been under some fairly dodgy management, hasn’t it? The website suggests not: “We provide you an inspiring and interesting work environment characterized by a wide range of opportunities to attain your personal goals.” We’re left to wonder if Marsalek is attaining his personal goals. Wherever he is. And in any case the website concludes with this unencouraging statement: “Unfortunately, there are currently no open positions.” Apart from in police cells awaiting the return of Marsalek, of course.

THE BLAME GAME

Meanwhile, the EU’s European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA) is conducting an inquiry of its own into the responses of BaFin and Germany’s Financial Reporting Enforcement Panel (FREP) and into Wirecard AG’s collapse, which is due to be completed by the end of October 2020. BaFin claims that it lacks the powers to enforce the EU’s Transparency Directive.

Steven Maijoor Chair of ESMA (the European Securities and Markets Authority) © Esma

ESMA was asked in a letter from the European Commission to investigate. “The assessment will focus on the application of the Guidelines on the Enforcement of Financial Information (GLEFI) by BaFin and FREP, the designated competent authorities for the supervision and enforcement of financial information in the Federal Republic of Germany under the Transparency Directive (TD).” Add to these problems the profound complexity of Wirecard’s business activities, handling cashless payments among a complicated network of credit card companies, banks and merchants, while according to Associated Press, much of the value shown in Wirecard’s balance sheets “was in the form of intangible financial factors such as accounting goodwill and customer relationships.” You can’t put a price on a smile and a nod. “ESMA also invited BaFin and the European Commission,” according to its own website, “in the country-specific onsite report, to investigate whether the TD is correctly transposed by Germany, given BaFin’s self-declared inability to comply with the GLEFI due to a lack of enforcement powers.” To make things worse, much of Wirecard’s activities took place in hard-to-follow and uncooperative Asian jurisdictions.

The Official Monetary and Financial Institutions Forum, OMFIF, writes on its website that the work must now begin to find out what went so badly wrong. “The first one, hardly unique to Germany, is the nexus between a lax market culture and a regulator captured by the industry which holds and promotes that culture. The remedy can only be to create a distance between the regulator and the regulated. Europe has already gone through this experience in the case of the banking union.” OMFIF suggested the creation of a supervisor at the European Central Bank, safely isolated from the risk of national pride getting in the way. The problem here is that Wirecard was too small to fall under ECB supervision, which left BaFin in charge. OMFIF says that Europe should make use of this crisis to reform its institutions and control. “The European Securities and Markets Authority,” it suggests, “an agency so far endowed only with weak coordination powers over national market supervisors, should be restructured and empowered with a new statute and legal basis. The conditions which permitted the Wirecard scandal to arise are still with us. They should be removed, not only in Germany, but in the whole of Europe.” OMFIF points out that something also needs to be done about regulatory arbitrage as more and more third country banks are repositioning to the European mainland, an issue made more serious and urgent because of Brexit.

Wirecard’s stunning rise should, perhaps, have rung more alarm bells than it did. From being a small company involved, according to DW, in “gambling and pornography”, it had risen to become one of the world’s largest and fastest-growing financial technology companies. This in itself was an achievement as Germany was generally regarded as somewhat behind the times in the world of financial technology. “Over the years, the understandable enthusiasm for a rare German financial tech success story gave way to the far more sinister force of wilful misbelief,” writes DW’s Business writer, Kate Ferguson. “In January of last year, when the FT reported on the suppression of an internal investigation of Wirecard in Singapore, Germany’s financial regulator, BaFin, responded by accusing the paper of attempting to manipulate the market.” Those whose job it was to keep an eye on things preferred, it seems, to talk up the company’s success while playing down any suggestion that it was not only holed beneath the waterline but that large parts of the hull simply weren’t there.

EU Commission Vice-President Valdis Dombrovskis © ec.europa.eu

The head of BaFin, Felix Hufeld, admits that the Wirecard affair is “a disaster” but has seemed reluctant up to the time of writing to admit any errors on the part of his organisation. His rôle is being investigated by EU officials from ESMA. According to the Austrian broadcaster, ORF, EU Commission Vice-President Valdis Dombrovskis told ‘Handelsblatt’: “On the commission side, we are examining the lessons to be learned from the Wirecard case for EU financial market legislation and whether we need to improve rules. In particular, we look at the transparency directive, the accounting directive, the rules for auditors and the regulations against market abuse.”

Wirecard’s stocks dive from 87.25 to 1.06 © Yahoo

The European Commission says “The EU Transparency Directive gives national supervisory authorities such as BaFin clear responsibilities to ensure that companies comply with their obligations regarding correct financial reporting. The European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA), based in Paris, sets common enforcement priorities for national supervisory authorities and in certain cases can also intervene directly in national supervision.” The Commission’s office in Germany says that if ESMA’s initial report reveals deficiencies in the enforcement of EU regulations on financial reporting by BaFin, “the EU should be ready to demand consequences.” The EU may well want to see consequences for Hufeld but it would be even happier to see Marsalek brought back to face the consequences of his bizarre alleged actions, if only Russia would cooperate. That fact that it won’t suggests a possible link with the Wirecard scandal that goes beyond a little investment and a rogue operative, though what Russia’s aims could have been are very hard to guess. The Wirecard scandal has been dubbed ‘Germany’s Enron’ by some observers.

The auditors who finally brought the scandal to public notice by refusing to sign off the accounts, EY, have also come in for heavy criticism. CNBC reports that the law firm Schirp & Partner have brought a class action lawsuit against the EY on behalf of Wirecard investors, alleging it failed to flag improperly booked payments on Wirecard’s 2018 accounts.

The German shareholders’ association, SdK, has also filed a criminal complaint against the auditors, targeting two current employees and one former staff member at EY. BaFin may have egg on its face over the scandal but it seems there is enough egg to go around and cover several faces. Oddly and ironically, the only people who seem to have emerged from the mess with any credibility are the FT investigating team, the Wirecard whistle-blowers and, most strangely of all, the hedge funds who shorted Wirecard stock and who have cleaned up because of its collapse. CNBC also reported a statement from EY, although they are not offering any further commentary on what happened at Wirecard. “Collusive frauds designed to deceive investors and the public,” the statement says, “often involve extensive efforts to create a false documentary trail. Professional standards recognize that even the most robust and extended audit procedures may not uncover a collusive fraud.” The statement is unlikely to deter either Schirp & Partner or SdK from pursuing their legal actions.

Every time it seems as if the mist surrounding the scandal is clearing, a new piece of information thickens it again. Now the news website EURACRTIV says the scandal could turn out to be much greater than has so far emerged. “Following reporting from Der Spiegel that the German chancellery had undertaken lobbying work on behalf of the scandal-hit Wirecard financial services company, the Greens, liberal FDP and Die Linke, who are in opposition, are now demanding a formal clarification from Finance Minister Olaf Scholz (SPD).”

Hasepost, based in Osnabrück, reports the very serious way the European Commission, especially its vice-President, Valdis Dombrovskis, is regarding the Wirecard scandal. “Dombrovskis is also considering depriving national authorities such as BaFin of oversight of large payment service providers such as Wirecard and transferring them to EU banking supervision,” reports the website. Dombrovskis has confirmed that this is under serious consideration and the Commission will present a Fin Tech Action Plan in autumn. “It will also look at how major third-party financial service providers will be subject to EU banking supervision in the future,” Hasepost reports Dombrovskis as saying.

Wirecard AG’s former CEO, Markus Braun, now faces additional questioning about alleged improper activities, according to the Swiss financial news website, Finanzen.ch. “Because of a share sale shortly before the Wirecard bankruptcy,” it reports, “the former company director Markus Braun is suspected of illicit insider trading. This was confirmed by the German financial regulator BaFin on Wednesday. This had been reported to the Munich public prosecutor’s office, said a BaFin spokeswoman.” Braun has rejected the allegation through his lawyer. Given that he presumably knew that the whole house of cards was about to come tumbling down around his ears, it seems almost petty to engage in insider trading to make a quick buck. It would be like carrying out an armed bank robbery and stopping on the way out to pinch the bank’s blotter, notebook and pen. In any case, given the seriousness of the allegations he’s expected to face, I would not have thought this latest accusation holds many terrors, other than as a further indication that illicit goings-on were going on. And for Wirecard shareholders, the news keeps getting worse. According to Finanzen.ch, the US Department of Justice is now reported to have launched an investigation into the German payment service provider. There are more allegations against the fallen financial payments firm: falsification of the balance sheet, falsification of documents, arrests, bankruptcy – all these are important keywords for the news situation around Wirecard in the past weeks. Now, says Finanzen.ch, “the scandal seems to be spreading even further. As the Wall Street Journal reported on Wednesday evening, the Department of Justice in Washington has launched an investigation into the German payment service provider. More specifically, it is said to be an online platform for buying and selling cannabis,” a scam with an estimated value of $100-million (€85-million).

Perhaps not surprisingly, Wirecard’s subsidiary in the US, Wirecard North America Inc., has put itself up for sale, with an investment bank coordinating the transaction, if a buyer can be found. It seems likely one will; it’s been reported that a hundred or so entities have expressed an interest in buying up whatever is left of Wirecard when the dust settles. Wirecard’s shares have not fallen to zero – at the time of writing they have risen from 1.59 to 1.8794 (the price fluctuates second by second) in three days – and some investors are hanging on to them, despite the fact that Munich prosecutors have raided the company’s offices. As long as there is still money to be made, of course, those who know how to make it will continue to sniff around.

But for now, the President of the Bundesbank, Jens Weidmann, says Germany must toughen up its auditing and accounting rules to prevent another billion-euro fraud. In a newspaper interview, Wiedmann admitted “we have to do more to prevent it in future”, with more powerful, enforceable rules and procedures given to German authorities. “For example, the audit process and the tasks, powers and liability of auditors should be reconsidered,” Weidmann told the newspaper. It now looks as if Wirecard had borrowed €3.2-billion under false pretences, with the money now believed to be lost. Since the sudden collapse of the company, German Finance Minister Olaf Scholz has proposed to toughen financial oversight of companies, “seeking to pre-empt an expected parliamentary backlash over the failure of regulators to spot the unprecedented fraud”, according to Yahoo Finance. “Scholz rushed out a reform agenda that would give financial watchdog BaFin greater investigative and enforcement powers, broaden its mandate to cover non-banking financial institutions and toughen penalties against lax auditors.” So don’t worry, the stable door is being firmly shut, even if the horse has not only bolted but had been seen to be packing its bags to leave for years. No-one in power wanted to heed the warnings or read the runes. As the old proverb goes, there’s none so blind as those that will not see.

Robin Crow

Click here to read the 2020 August edition of Europe Diplomatic Magazine