In Nintendo’s famously successful Super Mario series of computer games, Mario, an Italian plumber from Brooklyn in New York, saves the Mushroom Kingdom of Princess Peach from the game’s arch-villain, Bowser. Many are comparing the moustachioed cartoon hero with Mario Draghi, the former head of the European Central Bank (ECB), now drafted in to take over the running of his home country, Italy. Draghi was first nicknamed ‘Super Mario’ while heading the ECB, but he’s likely to find in Rome a less comfortable seat than was his chair in Frankfurt. Draghi is a banker and a successful one.

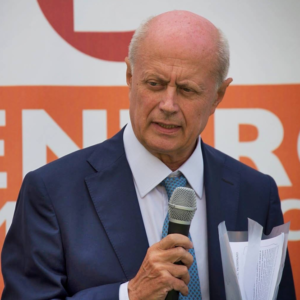

Apart from heading the ECB he had also been President of the Bank of Italy, but it was Italy’s President, Sergio Mattarella, who drew him into the political spotlight to make him Prime Minister.

It followed a political crisis – and Italy is no stranger to political crises – that forced the former premier, Giuseppe Conte, a fairly inexperienced former lawyer, to resign. Conte’s predecessor in the job, Matteo Renzi, withdrew his small Italia Viva party from the ruling coalition. Renzi had disagreed with Conte’s plans for spending Italy’s €200-billion share of the EU’s post-pandemic (and EU-wide) recovery plan.

Draghi has held several prestigious positions in his life but never one that aroused such emotion. He seemed almost overwhelmed by the responsibility handed to him. “I’d like to tell you that, in my long professional life, there has never been a time of such intense emotion and such ample responsibility,” he told the house of the Senate during his 55-minute inaugural speech which drew an impressive 21 rounds of applause. According to the Forbes website, 61% of Italians support him. For now, at least.

It was the Roman writer of satire, Juvenal, who said that the modern citizen only wants two things: bread and circuses. He also wrote: “Omnia Romae / Cum Pretio” – Everything in Rome has its price. Can Draghi provide both bread and circuses? And can he (and Italy) afford the price? Time will tell. In his inaugural speech he gave his top priority to tackling the pandemic. Coincidentally – or at least ironically – it was a pandemic recovery package that led to the resignation of Draghi’s immediate predecessor, Giuseppe Conte, who failed to get Italy’s squabbling parties to agree, despite being a member of none of them. Draghi’s pledge will have met with approval: Italy is currently seeing around 12,000 new Covid cases every day and 369 deaths. The spread of the disease is getting faster, too. He also spoke about the need for cooperation and urged Italians to forget the claim in many circles that his premiership is the result of a “failure of politics”. “Nobody is stepping back from their identity,” he said in his speech, “if anything, they take a step forward, in an unprecedented perimeter of collaboration, to give an answer to the country’s needs, to get closer to the daily problems of the families and firms that know well when it is time to work together, with no prejudice or rivalry.” If he can achieve that, he will have exceeded the dreams of all the emperors who ruled Rome and the consuls who preceded them. Perhaps the crisis that launched Draghi’s premiership was not so much ‘a failure of politics’ as a ‘failure of politicians’. Take a brief look at other recent incumbents and it would seem Draghi won’t need to do much to impress.

Apart from the inexperienced Conte, whose administration last just 16 months, there was Silvio Berlusconi, a former cruise ship crooner who promised reforms but ended up facing repeated court appearances.

Berlusconi was also famous for his “bunga bunga” sex parties. And no, I don’t know quite what “bunga bunga” means either, although I could hazard a guess. After such unimpressive predecessors, it would seem that Draghi has little to prove. Interestingly, in the crisis that followed Conte’s resignation, Berlusconi suggested that his Forza Italia party could be available for a larger government of national unity. “There is only one road ahead,” he proposed, “a new government that represents unity of the country in a moment of emergency.” Fortunately for Italy, it got that but with Draghi in charge instead.

THE FLYING ECONOMIST

Draghi wants to rebuild Italy from the bottom up, he told the Senate, just as it was done in the aftermath of the Second World War. He suggested that it would only work if everyone believed they were engaged in constructing a better future for everyone. “This is our mission as Italians,” he urged, “to give a better and fairer country to our children and grandchildren.” He told the present generation – his own generation – that they must be prepared to make the sorts of sacrifices their grandparents had done.

The big question here is: will that be enough? It’s by no means certain that the Italian people will remain supportive unless Draghi can achieve improvements for the citizens very quickly. The infamous advisor to leaders of Florence in the 15th to 16th centuries, Nicolò Machiavelli, wrote: “It is necessary for him who lays out a state and arranges laws for it to presuppose that all men are evil and that they are always going to act according to the wickedness of their spirits whenever they have free scope.” To put that in Nintendo terms for Super Mario, always be aware that the evil Bowser will be trying his hardest to mess up your plans. I can’t quite see Mario Draghi rushing through the streets seizing prizes and weapons with which to defeat his enemies like the computer game version, but he’s a fairly formidable character. As Anna Zanardi Cappon wrote on the Forbes website, Draghi’s appointment seems to have done some good. “The Italy of the last few days,” she wrote in mid-February, “is a renewed, confident Italy, hopeful in an unclear future, but already rosier, due to the not so obvious choice of the Government of Mario Draghi and a handful of brave heroes, who have abandoned comfortable positions earned over the years and lavish salaries, to become Ministers who must try to untangle a now Pathologically messy bundle. To them, few in truth, I grant my respect and my gratitude.” Nothing like piling on the expectations, eh?

Let’s take a look at Mario Draghi and how he got to where he is now. Born on 3 September 1947, he was brought up in Rome and educated by the Jesuits. He gained his first degree at the Salienza Università di Roma in 1970 before moving to the United States and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) where he gained a doctorate in economics in 1977. His early career was as an educator, teaching economics at the University of Florence, during which time he also served as an executive director at the World Bank, based in Washington DC. From 1991 to 2001, he was General Director of Italy’s Treasury, heading the committee that revised and renovated the country’s corporate and financial legislation. From 2002 to 2005, he was Vice Chairman and Managing Director of one sector of a huge investment bank, Goldman Sachs International. Goldman Sachs doesn’t always get a good press, as we shall see in a moment.

From 2006 until 2011, Draghi served as Governor of the Banca d’Italia. His time as governor at Italy’s central bank included the start of what’s been called ‘the Great Recession’ in 2008. During this time he was chosen to become the first Chair of the Financial Stability Board (FSB), which had replaced the Financial Stability Forum. The FSB is an international standard-setting body that monitors and makes recommendations about the global financial system. It does so by co-ordinating the work of national financial authorities and international standard-setting bodies as they strive to achieve strong regulatory, supervisory and other financial sector policies. The aim is to create a level playing field, so Super Mario was a sensible choice. After that, of course, he was appointed to run the ECB.

But back to the Goldman Sachs years. It was in 2009 that Rolling Stone magazine that first coined the nickname for the bank that would be hard to live down. “The world’s most powerful investment bank is a great vampire squid wrapped around the face of humanity, relentlessly jamming its blood funnel into anything that smells like money.” Criticism doesn’t come much more vicious than that. The long article alleged how successive American governments had caved in to demands from the bank in return for it providing lots of money – always with a good return. “The bank’s unprecedented reach and power have enabled it to turn all of America into a giant pump-and-dump scam,” the article said, “manipulating whole economic sectors for years at a time, moving the dice game as this or that market collapses, and all the time gorging itself on the unseen costs that are breaking families everywhere — high gas prices, rising consumer credit rates, half-eaten pension funds, mass layoffs, future taxes to pay off bailouts.” Goldman was also accused of selling dubious securities backed not by the cast iron mortgages promised but by large numbers they knew would fail. Its deliberate and cynical fraud cost a lot of innocent investors large sums of money; a friend of mine found his savings had shrunk by 10% because of it. Goldman Sachs will pay $5.06-billion (€4.16-billion) for its role in the 2008 financial crisis, the US Department of Justice said. The settlement, over the sale of mortgage-backed securities from 2005 to 2007, was first announced in January. The bank was penalised with a reduction in its earnings of $1.5-billion (€1.23-billion) after tax for one quarter, a civic penalty of $2.385-billion (€1.96-billion), $875-million (€720-million) in cash payments and $1.8-billion (€1.48) in customer relief. My friend got nothing back.

A number of reputations have become tainted through association with Goldman Sachs. Quite recently, for instance, the bank became involved with 1MDB, which was an investment fund set up by the Malaysian government that lost billions due to fraudulent activity. The global web of fraud and corruption led to a 12-year jail term for Malaysia’s ex-prime minister Najib Razak which he is appealing. Goldman Sachs called its involvement in the scandal an “institutional failure”. Goldman agreed to pay nearly $3-billion (€2.5-billion) to government officials in four countries to end an investigation into work it carried out for 1MDB. That work earned Goldman $600 (€500-million) for arranging the bond sales in 2012 and 2013. Investigators around the globe have also spent years investigating its involvement. In the end, the 1MDB scandal cost the bank more than $5-billion (€4.15-billion) and its Chief Executive, David Solomon, has had his pay cut by $10-million (€8.3-million) for the bank’s involvement in the scandal. But Goldman’s dubious reputation with the public (if not with the financial community) has not harmed Draghi. Unlike too many others, he emerged from the job with a clean bill of health.

His first actions as Italy’s Prime Minister have met with general approval. For instance, in response to the pharmaceutical company and vaccine-maker Astra Zeneca which had been defying the EU over where the vaccines went, he blocked the company from exporting 250,700 doses to Australia. It is hardly surprising that Canberra was not best pleased. The Italian Ministry cited its reasons for the action: it doesn’t consider Australia to be a vulnerable country; Italy and the EU had previously experienced shortages of supplies and delays from AstraZeneca; Italy also argued that too many doses were being exported outside the Union in comparison to those being supplied to EU countries. The Italians approved of the decision; they like a tough guy. So did the New York Times. “The move shook up a Brussels leadership that had seemed to be asleep at the switch. Within weeks, in part from his pressing and engineering behind the scenes, the European Union had authorized even broader and harsher measures to curb exports of Covid-19 vaccines badly needed in Europe.” In fact, the NYT sees Draghi as reasserting Italy’s place in the leadership of Europe. “In his short time in office — he took power in February after a political crisis — Mr. Draghi has quickly leveraged his European relationships, his skill in navigating EU institutions and his nearly messianic reputation to make Italy a player on the continent in a way it has not been in decades.” Princess Peach’s castle is looking safer by the day and Bowser’s chances of upsetting everything are fading, at least for the duration of Draghi’s administration.

He showed that side of himself again when European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen found there was no seat for her when she and European Council President Charles Michel met the Turkish President, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. It was clearly a snub and intended to underline Erdoğan’s sexist attitudes and his belief that women should be subservient. Draghi called him “a dictator”, which annoyed him considerably. “I felt very sorry for the humiliation that European Commission President von der Leyen had to undergo,” Draghi told a press conference. “I believe it wasn’t appropriate behaviour.” He also had advice for dealing with such macho leaders: “With these — let’s call them for what they are — dictators, which we however need to cooperate with … one has to be frank in expressing a diversity of views, opinions, behaviours, visions of society. And also has to be ready to cooperate to safeguard the interests of their country. This is important. We have to find the right equilibrium.” He made it clear that he doesn’t equate ‘manliness’ with bullying women, as some apparently do.

Turkey’s Foreign Minister Mevlüt Çavuşoğlu has condemned Draghi’s remarks and demanded that he withdraw them. He will not, of course. What’s more, the leader of one of the coalition parties in the government over which Draghi rules, Enrico Letta of the centre-left Democratic Party, has recently named a woman as one of his two deputies and given women eight of the party’s sixteen seats in its executive, despite having had to sack three men to create the vacancies. Erdoğan may not approve but Draghi, one assumes, probably does.

LEADING FROM THE FRONT

Ursula von der Leyen seems to have dwindled somewhat in importance as some of her actions have aroused comment and disapproval.

Meanwhile, Angela Merkel’s importance to Europe is weakening as the end of her term of office draws near. Then there’s Emmanuel Macron, who now seems more concerned with French matters than with European ones, especially with a general election looming. Draghi himself is held in such high respect by others, especially by the market, that there’s a risk that expectations may prove too high. Indeed, The Economist magazine, in its Charlemagne column, while praising Draghi, expresses some concern. “Bluntly,” it says, “Mr. Draghi’s government can write cheques because it is he who leads it.” It offers proof, too: “Earlier this month, his government announced plans to add €40-billion (2.4% of GDP) in stimulus, and bond yields barely budged”. At this rate people will be expecting him to walk across the surface of the Tiber. Having mentioned the imminent retirement of Angela Merkel, it’s possible Germany’s next government will include the Greens, who would expect to deliver “looser spending rules and deeper European integration”, both of which would meet with Draghi’s approval. He is also very committed to the eurozone and feels that failure to develop it fully could possible jeopardise the “long-term success of monetary union when faced with an important shock”.

There could surely be no greater shock that the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, but Draghi is already eager for Italy to hit the ground running in drawing back tourists. At an on-line meeting of tourism ministers from the Group of 20 wealthy nations, he announced a national vaccine pass, available from mid-May, a month before its EU equivalent goes on trial: “In mid-May tourists can have the Italian pass . . . so the time has come to book your holidays in Italy,” Mr Draghi said. “Our mountains, our beaches, our cities are reopening.” He assured potential visitors that there will be no quarantine either, “as long as they can prove that they have recovered from Covid, [been] vaccinated or tested negative.”

You will not be surprised to learn that the tourism industry looks set to be a major beneficiary of the EU’s €222.1-billion to restore the economy after the pandemic. Italy, in fact, gets the biggest share and tourism accounts for 13% of Italy’s economy. According to EuroNews, “Over a quarter of the money has been earmarked to digitally transform the economy and public administration, broadening access to high-speed internet service, especially in schools, and providing incentives to the private sector to digitise. Around €22.4-billion is aimed at “social inclusion” investments and programmes to boost training and employment opportunities for women and help cities improve access and opportunities for disabled people.” The aim of the measures, which include increased day care places, is to remove the obstacles that have, in the past, kept Italian women at home, looking after children, the elderly and those who are sick or disabled. It’s important because women accounted for more than half of the 456,000 jobs lost in Italy last year. With an EU target of reducing the emission of greenhouse gases by 55% by the end of this decade, it wants to see 37% of the money spent on helping to achieve carbon neutrality. Draghi’s proposal is to spend 40% of the money, €68.6-billion, on green initiatives, such as recycling, replacing public transport systems with low-emission vehicles while extending high-speed rail links and reducing water waste by improving the country’s waterways. It’s an ambitious programme.

The important thing to note is that when Draghi speaks, world leaders tend to listen and to believe. It’s widely believed that he single-handedly saved the euro from collapse while he was President of the European Central Bank (ECB), at a time when collapse looked imminent. How? With three simple words. At a conference in London in 2012, when Draghi was asked what he would do to save the euro, he replied: “Whatever it takes.” In other words, there was no step he would hesitate to take to protect and preserve Europe’s single currency. The speculators saw that the whole of the ECB’s considerable financial power would be opposed to any attempts to undermine the currency. His actual words were: “Within our mandate, the ECB is ready to do whatever it takes to preserve the euro. And believe me, it will be enough”. The markets settled and the currency survived, although he would prefer it to be more mature and more widely used.

Can he do the same for Italy’s battered economy? “It is not a question here of emphasizing its magical aspect,” wrote Anna Zanardi Cappon of Forbes, “but of acknowledging its restorative function that his reputation and expertise can convey, together with some of the good technical experts whom he has chosen to a relaunch the Italian economy. He had an articulate objective, to bring together various disciplines necessary for good governance.” Draghi has already pledged his support for gender parity and tax reform while positioning Italy firmly to being EU- and US-orientated. To read some of the reports one might imagine that Draghi is headed not only for ever-higher esteem and economic success but he could be a candidate for beatification.

A WORD OF CAUTION

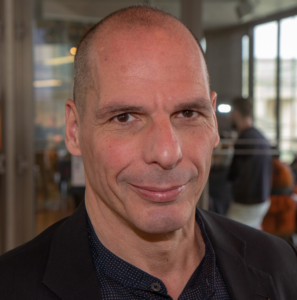

Of course, you can’t please everyone. Perhaps not surprisingly, even Draghi is not without his critics. At least one critic, anyway: Yanis Varoufakis, the one-time finance minister of Greece and currently leader of the European Realistic Disobedience Front (MeRA25) party and Professor of Economics at the University of Athens. He attacked Draghi, or at least one of his decisions, in a Tweet in March. “So predictable, so sad: Mario Draghi hired McKinsey to ‘organise’ Italy’s distribution of Recovery Fund monies. What next? Get the Mafia to re-organise the Ministry of Justice?” The Naked Capitalism website seems to think he has a point. “Independent of Varoufakis’ questioning McKinsey’s ethics, as we and many others have (see for instance our recent post, Goldman Is Evil But McKinsey Is Worse), the Greek economist is correct to call out how the Italian government is engaging McKinsey in a role that usurps democratic rule.”

In fact, the Draghi government’s spending plans for the EU bail-out fund seem to have met fairly widespread approval in Italy, so let’s see just what it is about McKinsey that Naked Capitalism doesn’t like.

“It is remarkable the way that McKinsey goes from train wreck to train wreck yet manages to depict itself as some sort of Corporate America Zelig: ever on the scene but not doing much of anything in particular,” Naked Capitalism says, crossly. “This is despite the fact (for instance) that McKinsey was singularly responsible for the biggest value destroying deal of all time, save maybe Bayer’s purchase of Monsanto, which was the Time Warner acquisition of AOL. McKinsey pitched AOL to the Time Warner board five times and the board had the spine to reject it only four times. Or how about the Enron bankruptcy? McKinsey was all over Enron every bit as much as Arthur Andersen had been but didn’t leave fingerprints at the crime scene like signing off on Enron’s financials…even though it was widely acknowledged as having approved of the accounting treatment that sank Arthur Andersen.”

In case you are not familiar with what the company does, this is from its own website: “McKinsey & Company is a global management consulting firm that serves leading businesses, governments, non-governmental organizations, and not-for-profits. We help our clients make lasting improvements to their performance and realize their most important goals.” The company’s advice hasn’t always turned out well for the client, it seems. McKinsey has come in for a number of attacks in the media, such as this one in The Atlantic, under the heading: “How McKinsey Destroyed the Middle Class: Technocratic management, no matter how brilliant, cannot unwind structural inequalities”. Management consultants, of course, advise directors on how to run their companies and sometimes they get things wrong (or wrong in the eyes of the workers at least), which is hardly surprising for a company that was set up 95 years ago. McKinsey advises 90 of the world’s 100 largest companies, but, as The Atlantic explained, “Managers do not produce goods or deliver services. Instead, they plan what goods and services a company will provide, and they coordinate the production workers who make the output.”

According to The Atlantic, McKinsey was at the forefront of fulfilling the aims set out by Milton Friedman, “The social responsibility of business is to increase its profits.” One way to do that was to get rid of expensive middle management, leave the running of a firm to its wealthy senior executives, assisted of course by hired-in business consultants when needed. Friedman, of course, was the profit-obsessed economist who once said that any executives not pledged to maximising profits were “unwitting puppets of the intellectual forces that have been undermining the basis of a free society these past decades.” In other words, who cares about the workers, line your own pockets. His idea of a free society and the workers’ own would seem to be very far apart. Friedman did not believe in conscience getting in the way of making money and seemed to want company bosses to follow a moral plan devised by Charles Dickens’ Fagin: take whatever you want and can get away with. McKinsey applied Friedman principles and, over a fairly short time, the career structure that trained new staff to pass through middle management on their way to the top was swept away. No more middle management equates to no more middle classes but lots of consultancy fees for companies like McKinsey. The company was criticised for the ruthlessness of its advice, always in pursuit of the Friedman mantra of maximising profits at any cost. McKinsey, for instance, advised Purdue Pharma on how to achieve that, allegedly suggesting that it should drive the sales of OxyContin, a highly addictive opioid whose widespread sales contributed to the opioid crisis that has devasted families and communities across the United States, according to the New York Times. Once again, forget any moral imperative, all that matters is profit. All of this leads some in Italy to question Draghi’s decision to hire McKinsey when he could have sought the advice of Italy’s home-grown economists.

STORM CLOUDS OR A LIGHT SHOWER?

While Draghi has been bathing in the warm approbation of the Italian people, his hiring of a successful but not uncontroversial American management company is not his first act to raise questions since taking office. DiEM25 reports on its website that over the first few weeks of his premiership, Draghi “hired Francesco Giavazzi (the infamous theorist of the expansive austerity) as economic consultant, but also Sirena Sileoni, deputy director of Bruno Leoni Institute (whose motto is ‘Ideas for the free market’), where a paper was published a few months ago claiming that the blocking of layoffs causes a bubble ‘which sacrifices the freedom of dismissal by companies and the efficient reallocation of productivity which would be ensured in the medium-long term, by the free deployment of the productive forces’.

And to conclude (for now) the unexpected contract with McKinsey.” It’s hardly surprising that the decision has drawn criticism from the left: McKinsey is no poster-boy for workers’ rights. Some also see the contract as suspicious because it is so small – just €25,000 – and seemingly of little value to McKinsey. Italy’s Economy Ministry said in a statement that it had asked McKinsey to assess the plans already prepared by the other EU countries and to provide “support for monitoring the finalization of the (Italian) Plan”. Draghi’s government has said that it remains in charge of making the decisions, leaving many to wonder exactly what McKinsey’s interest may be. It’s not known for its charitable work. Knowing Draghi’s Teflon reputation for emerging from any situation without a stain on his character, he will presumably explain his decisions at some point. Anyway, while he may choose to listen to advice, he’s not obliged to follow it.

“He’s a very sophisticated politician who cannot be reduced to the röle of banker,” Bruno Tabacci, a centrist politician who has known Draghi for several decades, told Politico. “When one has run the ECB for eight years, having to deal with the head of the Bundesbank and succeeding in saving the eurozone, what more do you want?” While he was at the ECB, he kept a small coterie of close advisors around him, but he mainly took decisions on his own, sometimes choosing the exact opposite path to the one recommended. He has always been his own man. He is going to need to be, to prove to doubting Italians (and Yanis Varoufakis) that he will never be in the pocket of McKinsey, nor of anyone else. If he can survive working for Goldman Sachs without drawing criticism, he clearly thinks for himself. He will certainly need all his skills if he is to save Italy, which has the second highest national debt in the EU.

Is he really Super Mario? So far, Princess Peach seems hopeful and her Mushroom Kingdom, the “Regno dei Funghi”, would seem to be in safe hands. However, questions over how much he knew of Goldman’s activities in apparently advising Greece on how to circumvent EU budget rules through credit swaps have been answered and Draghi is in the clear. The affair did not prevent his appointment to head the ECB, so perhaps the doubts and the doubters are now behind us. As he has done before, Draghi will act according to his own ideas. For the time being, it seems, the villainous Bowser will be defeated by Super Mario and his hopes for seizing the Mushroom Kingdom must rest on the fact that Super Mario is growing old. Finding someone else to take on the many and difficult challenges will not prove easy. Meanwhile, Italy can hope again. As Draghi said in his inaugural speech before the Italian Senate, much has changed since populist parties fought each other for power in the 2018 election: “Those were the days of anti-euro protests, of flirting with the idea of Italy leaving the EU, of little wars with France and Germany, of dreams of happy degrowth and denial of global warming. Of simple and illusory answers to complex problems that could not be solved with Italian-style sovereignist formulas.” Times have changed. Bowser must be tearing his computer-generated hair out.