There are a number of commonly-used acronyms that suggest things that are worrying and possibly dangerous: AIDS, of course, stands for acquired immune deficiency syndrome. It’s used to describe a number of potentially life-threatening infections and illnesses that happen when your immune system has been severely damaged by the HIV virus. Then there’s AWOL: absent without official leave, normally used for a member of the military who has deserted his or her duties and taken an unofficial break. Some American politicians, especially Democrats, might be wary of the acronym POTUS, which stands for President of the United States. But if you really want to annoy Margrethe Vestager, Executive Vice President of the European Commission with the ungainly title of “Commissioner for a Europe Fit for the Digital Age” (who thinks up these ludicrous titles?), as well as Competition Commissioner (much more sensible) just try mentioning GAFA. It’s an acronym that first appeared in the French media, standing for four of the US-based tech giants, Google, Apple, Facebook, and Amazon. Where, one may well ask, is Microsoft in that list? The media has cast Vestager as the nursery tale character, Jack the Giant Killer. In the English folk story, Jack encounters giants with one head, two heads and even three heads, defeating them all. Vestager has taken on one with four heads and, so far, has not emerged the winner. One giant, you may recall, in the separate but related story of Jack and the Beanstalk, finds Jack in his house and announces his intention to defeat his attempts to relieve him of his wealth with the words:

“Fe, Fi, Fo, Fum.

I smell the blood of an Englishman”

In this case, for the tech giants, it’s not an Englishman but a Danish woman, but the sentiment is similar.

Back in 2016, the European Commission had ordered that Ireland’s favourable treatment of Apple Sales International and Apple Operations Europe had amounted to state aid, and, as such, illegal under EU law.

General Court of the European Union © Court of Justice of the European Union

General Court of the European Union © Court of Justice of the European Union

The court at that time ordered Apple to pay back €13-billion in back taxes to the Irish government. Both Apple and Dublin appealed against the judgement and now the General Court of the European Union (GCEU) has overturned the original decision. It’s a big set-back for Vestager, who had become the hate figure of US tech corporations and who had been described by President Donald Trump as “the tax lady”. Apple’s chief executive had also derided the original verdict. The EU’s argument was that by allowing Apple to round up its earnings from Europe, Africa, India and the Middle East into the earnings of one Ireland-based entity, it had allowed the company to avoid taxation on a massive scale. The EU contested that by bundling its earnings into a low-tax state with special taxation agreements, it had successfully avoided paying Irish taxes to the tune of almost €13-billion between 2003 and 2014.

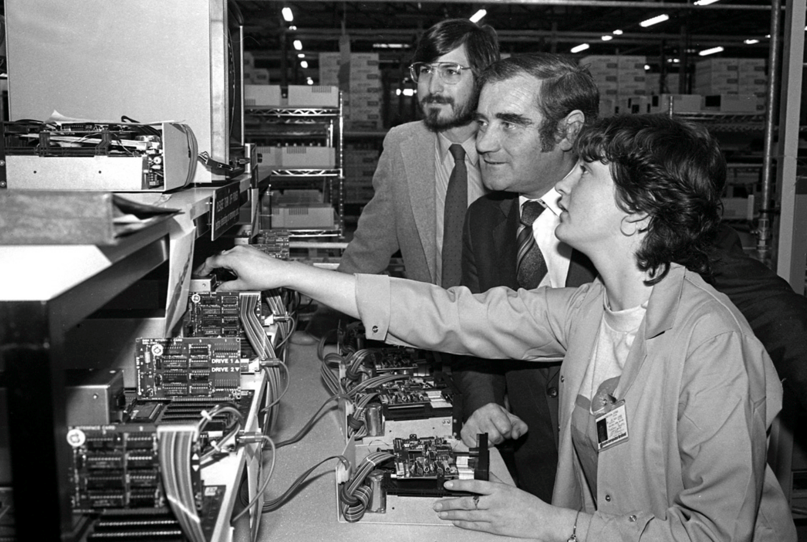

Steve Jobs visits Apple’s new facility in Cork, October 1980 © Apple

Steve Jobs visits Apple’s new facility in Cork, October 1980 © Apple

Apple, which manufactures iPhones in Ireland, had argued that the earnings should not have been taxed in Ireland anyway because they were all destined to be transferred to the United States. The Irish government has also welcomed the GCEU’s decision, claiming that Dublin had imposed the appropriate tax level and that Apple had not been given special treatment. Oddly, the company was paying tax in Ireland at the astonishing rate of less than 1% for two decades, averaging 0.005% in one year. Vestager may appeal against the decision at the European Court of Justice, but that has to be done within two months of the judgement. Most experts think she will not. If she does, the move will probably be welcomed with open palms by the several lawyers involved. She may need more than the legendary Jack’s magic sword, cap of knowledge, cloak of invisibility and shoes of swiftness to defeat the giant GAFA, who has the staunch support of the POTUS, to re-use an earlier acronym.

The issue of corporate tax avoidance was supposed to have been settled with the entry into force of binding new anti-abuse measures on 1 January, 2019.

Pierre Moscovici, the French politician and former Minister of Finance for France, who served as European Commissioner for Economic and Financial Affairs, Taxation and Customs from 2014 to 2019 © Wikipedia

Pierre Moscovici, the French politician and former Minister of Finance for France, who served as European Commissioner for Economic and Financial Affairs, Taxation and Customs from 2014 to 2019 © Wikipedia

Pierre Muscovici, the French politician and former Minister of Finance for France, who served as European Commissioner for Economic and Financial Affairs, Taxation and Customs from 2014 to 2019, clearly hoped it would put an end to tax dodges by big multi-nationals. At the time, he said “The battle is not yet won, but this marks a very important step in our fight against those who try to take advantage of loopholes in the tax systems of our member states to avoid billions of euros in tax.” Well, it looked promising at the time, but big corporations can afford very clever tax lawyers and they would rather pay them lots than pay even more in taxes. The rules introduced then were based on standards developed by the OECD in 2015. Under them, member states were obliged to tax profits moved to low-tax countries where the company does not have any genuine economic activity. The rules also discouraged companies from using excessive interest payments to minimise taxes, with member states being compelled to limit the amount of net interest expenses that any company could deduct from its taxable income. Member states were also empowered to tackle tax avoidance schemes in cases where other anti-avoidance measures could not be applied.

SPECIAL OFFERS

Of course, to defeat the crafty tax-avoidance methods employed by the tech giants and other multinational corporations, what the world needs is a global tax system. The OECD was holding talks with that aim in mind, but the United States has opposed the idea and it has been shelved, at least for now. Even some European capitals are against forcing the tech giants to pay their taxes where they actually earn their profits. Ireland’s defence of the Apple deal may be connected with the fact that Ireland has a corporate tax rate of just 12.5%, which makes the country very appealing to large American corporations looking for an EU base. In any case, with the UK out of the EU, Ireland is now the only English language member.

Seán Kelly, member of the European Parliament for Ireland South since 2009 © finegael.ie

Seán Kelly, member of the European Parliament for Ireland South since 2009 © finegael.ie

An Irish MEP, Seán Kelly, once told me he would strongly oppose any moves to force Ireland to increase the rate. Ireland’s distance from mainland Europe means it has to take fairly drastic measures to attract inward investment, and the fact that it now has no land border with another EU member state makes that more important than ever. Its tax rate is rather like the “buy-one-get-one-free” offers made by supermarkets to lure in shoppers.

As it is, large corporations with a presence in several tax jurisdictions often try to turn a profit wherever the tax will be lowest. This is hardly surprising, of course; who wouldn’t? What the latest rules seek to do is to clamp down on what are called BEPS. This is yet another acronym, this one referring to Base Erosion and Profit Shifting. In fact, it refers to tax avoidance strategies that exploit ‘loopholes’ in tax regulations by artificially moving profits to jurisdictions where there is a more favourable tax environment. More than a hundred countries and jurisdictions are currently collaborating as part of a co-ordinated approach, led by the OECD, to tackle tax avoidance by tackling BEPS. As large corporations have spread and become more complicated and sophisticated, so their tax experts, accountants and lawyers have developed equally sophisticated and often extremely opaque methods of tax planning. Why not pay tax where the tax rate is lowest? Indeed, why pay taxes at all if you can get away with not doing it? Of course, though, the losers in this battle are inevitably us, the citizens, deprived of the revenue our governments could do with to provide the services we expect. It’s been estimated that BEPS abuse costs the world’s tax gatherers between $100-billion and $240-billion (€86-billion and €206-billion) a year.

Margrethe Vestager © European Parliament

Margrethe Vestager © European Parliament

One of the abuses the latest EU rules are designed to tackle is what are called ‘hybrid mismatches’, which the OECD defines as follows: “Hybrid mismatch arrangements are used in aggressive tax planning to exploit differences in the tax treatment of an entity or instrument under the laws of two or more tax jurisdictions to achieve double non-taxation, including long-term taxation deferral.” In other words, claim the same expenditure (perhaps described differently) in more than one tax jurisdiction. The rules were introduced in the wake of the 2008 financial crash, when tolerance of financial shadiness plummeted. The problem arises in keeping up with the multinationals, which can move around and adjust to whatever new rules are brought in, to try to get them to pay their share. The OECD again: “Halfway through 2020, the world is now facing the prospect of an even more severe economic downturn as the economic impact from the COVID-19 crisis continues to unfold. As a result, the public’s tolerance for tax avoidance is expected to reach historic lows. Fiscal measures, many of which are ultimately funded by public revenues, are a critical tool in the fight to mitigate the negative impact from this economic shock, and tax administrations are oftentimes on the front lines of providing relief to taxpayers.”

WITH SWORD, SHIELD AND CALCULATOR

In June 2016, the OECD/G20 Inclusive Framework came to fruition as its 82 members attended its inaugural meeting in Kyoto, Japan and the implementation of BEPS began in earnest. Its membership has since swollen to 135 countries. The work continues, of course, as the OECD report states: “In January 2020, the OECD/G20 Inclusive Framework at its plenary meeting reaffirmed its commitment to reach a consensus-based long-term solution by approving the ‘Statement by the OECD/G20 Inclusive Framework on BEPS on the Two Pillar Approach to Address the Tax Challenges Arising from the Digitalisation of the Economy’. Building on the Unified Approach released by the OECD Secretariat in October 2019, the Statement included an ‘Outline of the Architecture of a Unified Approach on Pillar One’, as well as an updated Programme of Work, which identified 11 building blocks where further work was required to develop the solution. A progress note on Pillar 2 was also agreed.” The problem is that, ingenious as those fighting tax avoidance may be, the accountants and lawyers employed by the corporations are even more so, and almost certainly better-rewarded for their efforts.

The accountancy firm, BDO, has warned firms based in the UK and the EU to be aware of what the new rules – essentially the ‘The International Tax Enforcement (Disclosable Arrangements) Regulations 2020’ – mean.

The accountancy firm, BDO © Bdo

The accountancy firm, BDO © Bdo

“The Directive provides for the mandatory automatic exchange of information between member states about certain cross-border arrangements. It is part of the European Commission’s ongoing work on promoting tax transparency and preventing international tax avoidance.” And in case you live in the UK and think that being based in a post-EU jurisdiction exempts you from any new regulations Brussels may introduce, think again. “The UK Government has committed to participating fully, notwithstanding withdrawal from the European Union,” warns BDO. “The regulations come into force, and the first reports will be made, on 1 January 2021. However, the Directive requires that relevant arrangements entered into from 25 June 2018 must be reported. Organisations and individuals affected by these rules will, therefore, need to interrogate their records for the last two years to identify arrangements that are now subject to a requirement to report. Going forward, reporting will be required within 30 days of certain trigger events (broadly, initiating a relevant reportable arrangement).” BDO further warns that most of the arrangements deemed to be ‘reportable’ will have a tax advantage of some sort, but that the rules go further and cover arrangements without an obvious tax advantage. “In particular, they include transfers that are ‘base erosive’ simply in virtue (sic) of transferring certain assets or businesses from one jurisdiction to another. They also cover arrangements that may be designed to frustrate EU or OECD rules on transparency (e.g. circumventing the Common Reporting Standard or obscuring beneficial ownership of certain assets). While the OECD’s 2018 model disclosure rules on tax transparency do not have the force of law, they will be used as a source of interpretation of the EU rules.” BDO, in case you were wondering, stands for Binder Dijker Otte, a firm with 80,000 partners that operates in 162 countries, so is clearly experienced in cross-jurisdiction tax affairs.

It would be a mistake to imagine tax money being siphoned off to some palm-fringed tax haven, lapped by waves and filled with largely empty offices with just brass plates to show the theoretical presence of some bank, financial institution or firm of accountants. The accountancy outfit NO MORE TAX (the capitals seem to be part of the title) offers clients ways to minimise their tax payments legitimately and in a way that is all above board. They issued this warning: “In the first part of 2019, the European Parliament issued a report which argues that seven EU countries, namely, Belgium, Cyprus, Hungary, Ireland, Luxembourg, Malta, and the Netherlands, display traits of tax havens and facilitate aggressive tax planning.” In those countries, according to the European Parliament, the business of aggressive tax avoidance is conducted fairly openly. “The operations allowed large companies, such as Allergan, Apple, Disney, GlaxoSmithKline, IKEA, Koch Industries, Nike, and Skype, to create tax optimization opportunities that served little or no commercial purposes,” says NO MORE TAX. “The seven countries identified by the report include some of the smallest nations of Europe and together account for less than 9% of the total population of the European Union.” BDO itself has offices in Belgium, the Netherlands and Bulgaria.

Apple New Central World in the heart of Ratchaprasong, Bangkok © Apple

Apple New Central World in the heart of Ratchaprasong, Bangkok © Apple

HUMBLE PIE

Multinationals will, of course, continue to look for ways to minimise their tax commitments; it’s their legal duty to their shareholders. It’s Vestager’s duty to try to stop them wriggling out of too many. Her defeat in the case of Ireland and Apple is a huge blow. It was viewed in Europe as a matter of prime importance; losing the case puts her on the back foot. Some have argued before that state aid legislation is the wrong way to tackle tax avoidance issues, rather like trying to punish a bank robber by charging them instead with trespass on bank property or not having the appropriate licence for the gun being used. Vestager has come in for a lot of personal criticism, especially from politicians in Paris and Berlin. As the Politico website reports, “Both the French and Germans are ramping up pressure on her to push the competition rule book in a more geopolitical direction, hoping to forge EU champions in the face of US and Chinese rivals, but the Apple case is fast turning into a textbook study of how hard it is to marry strategic ambitions with highly technical legal investigations.” It seems the multi-headed giant was just too feisty for Jack on this occasion.

Tim Cook and Leo Eric Varadkar, former Taiseiseach (head of the Government of the Republic of Ireland)

Tim Cook and Leo Eric Varadkar, former Taiseiseach (head of the Government of the Republic of Ireland)

Even so, she remains combative, despite her department’s run of defeats over tax. She explained that of some €16-billion of Apple’s reported profit from its Irish subsidiary in 2011, Ireland only considered €50-million to be subject to Irish tax. The Commission will continue to look into aggressive tax planning measures, but Vestager conceded that what was really needed was “a change in corporate philosophies and the right legislation to address loopholes and ensure transparency.” With the United States blocking further work on the idea by the OECD, progress in that area looks unlikely for the time being.

For Vestager, her policy of using the rules on state aid to attack suspicious tax arrangements have met with only limited success.

Starbucks Virtual Backgrounds 2 Palma de Mallorca © Starbucks

Starbucks Virtual Backgrounds 2 Palma de Mallorca © Starbucks

Without a doubt, the ruling on Apple is the biggest blow so far, but in September of 2019 she lost a similar case against Starbucks, although she won one against the car-maker, Fiat. The court ruled that in the case of Starbucks, the Netherlands was entitled to grant its favourable tax arrangement to the coffee roaster and that the sum of €25.7-million could not be clawed back as Vestager had demanded. The way the system works was explained in the periodical, Accountancy Daily: “The case centred around use of the arms’ length principle with two prongs to the Commission’s argument. It disputed the level of royalties paid to a Starbucks subsidiary, Alki, which was UK based, for coffee roasting expertise, as well as arguing that Starbucks Manufacturing paid inflated prices for green coffee beans from another subsidiary in Switzerland, further reducing its tax liability.” But the court said no offence had been committed and Starbucks Manufacturing BV, or SMBV, can keep the money. The ruling of the GCEU said “As regards the amount of the royalty paid by SMBV to Alki, according to an analysis of SMBV’s functions in relation to the royalty and an analysis of comparable roasting agreements considered by the Commission in the contested decision, the Court finds that the Commission failed to demonstrate that the level of the royalty should have been zero or that it resulted in an advantage within the meaning of the Treaty.” Fiat Chrysler Finance Europe was not so lucky. The court agreed with the Commission that its financing entity should be treated like a bank and all of its capital taken into account, which is why it has been obliged repay €20-30-million to Luxembourg. Other cases are pending that involve other multinational companies. Vestager had more success in the past, when she successfully imposed huge fines on Amazon, Google, Qualcomm and other large multinationals for violating anti-trust laws.

Vestager’s rôle at the Commission was seen as being at risk following elections in Denmark last year which saw a change of government. The Prime Minister, Mette Frederiksen, elected in 2019, is a Social Democrat, Vestager is a Liberal, but Frederiksen told the Danish media at the time that her compatriot had done a good job in Brussels and would be nominated for a second stint at the Commission. She was, returning as part of the team headed by President Ursula von der Leyen.

The headquarters of Qualcomm in the La Jolla area of San Diego, California

Vestager remains as keen as ever to rein in the more avaricious of the big corporations. She told Ravi Agrawal, the managing editor of the publication Foreign Policy in its summer 2020 edition, that she wants to protect the more honest companies that abide by the law. “This is my sixth year as a law enforcer, and I see so many businesses that really make an effort to do things by the book and that struggle to innovate and to present the best possible service to their customers. And then I see a few companies—some that are returning customers where we keep receiving complaints—and we keep finding issues that give us reason to hand out big fines.”

Denmark Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen © Wikicommons

Denmark Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen © Wikicommons

CROSSING BORDERS, SAVING MONEY

In point of fact, finding a good way to tax corporations with a presence in several countries is not easy. In fact, one might say, it’s very taxing. As Professor Thomas Piketty wrote in his highly-acclaimed 2014 book, Capital in the Twenty-First Century, some common activities may be viewed as borderline criminal by tax authorities but as legitimate ways to minimise their tax liabilities by the companies concerned. “The problem with the current system,” Piketty writes, “is that multinational corporations often end up paying ridiculously small amounts because they can assign all their profits artificially to a subsidiary located in a place where taxes are very low; such a practice is not illegal, and in the minds of many corporate managers it is not even unethical.” Referring to the eurozone in particular, Piketty urges switching to a system under which corporations would make a single declaration of their profits at the European level, and then tax that profit in a way “that is less subject to manipulation than is the current system of taxing the profits of each subsidiary individually.” Piketty believes that EU member states should adopt a different method of collecting corporate taxes. “It makes more sense,” he argues, “to give up the idea that profits can be pinned down to a particular state or territory; instead, one can apportion the revenues of the corporate tax on the basis of sales or wages paid within each country.”

Hairul Azlan Annuar, Associate Professor at the International Islamic University of Malaysia © Researchgate.net.png

Now here’s a statement that looks to be self-evident (but isn’t really): “The most obvious benefit of being tax avoidant is the cash savings from the taxes avoided.” So wrote Hairul Azlan Annuar, Associate Professor at the International Islamic University of Malaysia, Ibrahim Aramide Salihu, PhD, and Siti Normala Sheikh Obid, also from the International Islamic University of Malaysia, in a paper on corporate ownership, governance and tax avoidance. The self-evident statement clearly has some subtle points. Their report was produced for a 2014 international conference in Kuala Lumpur and published in Science Direct. “The cash savings lead to increased cash flow to the firm which offers it the opportunities for further investments and in turn increases the firm’s value,” it argues. “The shareholders’ wealth is also enhanced in terms of more dividends, and increased shares value. The managers are also not left out of these benefits given the compensations for effective tax management. In fact, the managers’ compensations are determinants of tax avoidance practices in most cases.”

The reasons for corporations to avoid tax if they can are very obvious (and tax avoidance is, of course, very different from tax evasion. It’s legal, for a start). So, too, are the reasons for trying to make it as difficult as possible. Cash-strapped governments do not like to see wealthy businesspeople buying third homes in a sun-drenched tax haven and a yacht to use while they’re there, when essential services within the country are running out of cash. It’s not just in Europe that tax reform is needed, either, but equally on the other side of the Atlantic. The American economist Joseph Stiglitz in his book The Great Divide, highlights the way in which tax policies there encourage multinational corporations to seek ways to avoid paying them which also, incidentally, impact in Europe. “Taxing multinational firms on their global income would close what might be called the Apple-Google loophole,” he suggests. “Globalization has given these companies new opportunities to dodge taxes by claiming that their immense profits originate not from the ingenuity of their American researchers or the seemingly limitless demand from American consumers for their products but from a few employees scattered across low-tax jurisdictions, such as Ireland. By taxing all corporations on the basis of production and sales here, we can raise significant revenues to create jobs and spur growth.”

It’s the job of tax authorities to seek out the subtle little tricks employed by some large corporations to retain as much as possible of their profits free of tax. The General Anti-Abuse Rule (GAAR) of the EU’s Anti-Tax Avoidance Directive (ATAD), which came into force on 1 January 2019, provides a way in. “In computing corporate tax liability,” it reads, “the tax authority of a Member State may ignore an arrangement or series of arrangements which are not genuine under the relevant facts and circumstances if it determines that the main purpose or one of the main purposes of the arrangement is to obtain a tax advantage that defeats the purpose of the applicable tax law. A non-genuine arrangement is an arrangement that was not put into place ‘for valid business reasons which reflect economic reality.’ The GAAR supplements specific anti-abuse rules under national legislation and in that sense is intended to cover gaps in those specific rules.”

The Central Bank of Ireland © Wikicommons

The Central Bank of Ireland © Wikicommons

The EU has made a proposal that would have forced multinational companies to reveal how much profit they make in each EU member state and also how little tax they pay in each. It may sound like a sensible and measured proposal but twelve countries voted against the idea, Ireland being one of them. It had been estimated that such a rule would have cost the GAFA group some €500-billion a year in tax, which they currently avoid by shifting their profits from high tax countries, such as Germany, France and the UK, to those with low tax regimes, such as Ireland but also Luxembourg and Malta. As an illustration, Ireland’s corporate tax rate can be as low as 6.25%, compared with 15% in Germany, 31% in France (reduced to 28% if the turnover doesn’t exceed €250-million for this year only), and 19% in the UK. The Irish Fiscal Advisory Council (IFAC) has warned that accepting the EU proposal would have done enormous damage to the Irish economy, where the corporate taxes paid to Dublin by the big multinationals, despite the low tax rate, account for half of all the corporate taxes paid there, despite coming from just ten companies. The other countries that voted against the plan included Austria, Cyprus, Croatia, Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia and Slovenia. Sweden voted against for unrelated reasons and Germany abstained. The big tech companies must really love the EU member state governments, even if they often annoy Vestager.

Margrethe Vestager and Ursula Gertrud von der Leyen President of the European Commission

Margrethe Vestager and Ursula Gertrud von der Leyen President of the European Commission

So where does the money go while it’s hiding from the tax authorities? According to the German NGO Transparency International, it sometimes goes to tax havens where it cannot be touched. “On 5 December 2017, the EU adopted its first blacklist of tax havens, which, however, did not do much to fill the current legislative gaps,” reports the organisation. “The tax havens list, as of now, remains mostly a tool to name and shame the 17 jurisdictions it includes. Despite the potential it has to encourage listed jurisdictions to adopt transparency reforms in their national legal frameworks, the list currently does not envisage sanctions, neither for the jurisdictions themselves nor for European companies making use of them.” One deterrent could by Public Country-by-Country Reporting (CBCR), but although this has been under discussion in the EU since 2016, it still remains in limbo, despite the fact that it would almost certainly curb some of the excesses. “Even though this is well-known, why is the EU not acting upon it?” asks Transparency International. “The European Commission published its proposal already in April 2016 and the European Parliament adopted its position in July 2017. Ever since, progress on the file has been stalled and the EU has struggled finding an agreement. At the end of 2017 the EU Council has yet to adopt its position before entering into trilogue negotiations with the other two EU institutions.” In other words don’t hold your breath.

I still recall the angry but oddly prophetic words of the late Alex Falconer, a Scottish Labour MEP, on the day the World Trade Organisation with its various tools and mechanisms was agreed. “You mark my words,” he said, poking me in the chest with his finger, “from now on all the big decisions won’t be taken by elected politicians. They’ll be taken behind closed doors by members of corporate boards!” This was long before the tech giants and even before the Internet and electronic communications came along, but I rather think he may have had a point.

Anthony James

Click here to read the 2020 August edition of Europe Diplomatic Magazine