Benjamin Franklin was right when in 1789 he wrote, in a letter to a friend, “In this world nothing can be said to be certain, except death and taxes.” He wasn’t the originator of the phrase, although he is normally credited with it. Daniel Defoe has a stronger claim, writing in ‘History of the Devil’ in 1726: “Things as certain as death and taxes, can be more firmly believed.” How very true. With the Covid-19 pandemic upon us, the death part is sadly all too common now; the taxes will come later, when all the stimulus measures have to be paid for. Or so one might think.

President Sergio Mattarella (left) with the Prime Minister of Italy Giuseppe Conte © Wikicommons

The President of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, was one of the speakers at an event organised by the Prime Minister of Italy, Giuseppe Conte, which was described as the ‘Estates General’, a week-long event to look at ways of finding enough money to cover the massive damage caused by the Covid-19 pandemic. For the historically minded, this was originally the consultative assembly of the different classes or ‘estates’ that advised the king of France before the French Revolution but which had no powers. But I digress. The Italian government invited employers, unions, political parties and the representatives of international bodies, including Harvard University and MIT, to Rome’s Villa Pamphili palace for the discussion, although Italian opposition parties boycotted the event, one of their leaders describing it as “a show”. But in her speech, von der Leyen got it right on the money. “We, the European Union,” she said, “are, for the very first time, borrowing money from our children.” Clearly, we didn’t ask them first if they minded. “We shall not, as sometimes our member states did, borrow from our children just to spend the money today. Today, we invest for Europe’s next generation.” The question arises (and it’s impossible to answer): will our children – and, indeed, our grandchildren and great grandchildren – think we made a good job of spending their inheritance? In the village where I live in leafy Lincolnshire, England’s oldest canal wends its way and, especially in summer, it hosts narrowboats, former freight carriers now converted into floating leisure-time habitations whose owners can move them every few days to a new location. One of the regular visitors has been named by its owners ‘The Kids’ Inheritance’. If this is what the EU is doing, we need to ensure it never sinks.

The coronavirus pandemic came out of nowhere. No, I don’t mean it didn’t have an origin; it clearly did, probably in or around Wuhan in China. Pointing a finger of blame doesn’t help anyone and every country has suffered the consequences. But it was unexpected. Its scale and spread shocked everyone and left the experts scratching their heads. For governments around the world, it presented a massive, unprecedented challenge. The global economy, bubbling along nicely, suddenly went over a cliff and politicians were obliged to find ways to save their countries’ industries and businesses, as well as the lives of their citizens. And what do panicking politicians do when facing an unexpected crisis? They throw money at it, of course, most of which has to be borrowed. It’s very difficult to assess exactly how much because the methods used are many and various. Mostly, they take the form of fiscal-easing measures and Germany, Italy and the UK have each announced more than 20% of their GDP in fiscal support, with France a short way behind with 17.5%.

President Sergio Mattarella (left) with the Prime Minister of Italy Giuseppe Conte © Wikicommons

The President of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, was one of the speakers at an event organised by the Prime Minister of Italy, Giuseppe Conte, which was described as the ‘Estates General’, a week-long event to look at ways of finding enough money to cover the massive damage caused by the Covid-19 pandemic. For the historically minded, this was originally the consultative assembly of the different classes or ‘estates’ that advised the king of France before the French Revolution but which had no powers. But I digress. The Italian government invited employers, unions, political parties and the representatives of international bodies, including Harvard University and MIT, to Rome’s Villa Pamphili palace for the discussion, although Italian opposition parties boycotted the event, one of their leaders describing it as “a show”. But in her speech, von der Leyen got it right on the money. “We, the European Union,” she said, “are, for the very first time, borrowing money from our children.” Clearly, we didn’t ask them first if they minded. “We shall not, as sometimes our member states did, borrow from our children just to spend the money today. Today, we invest for Europe’s next generation.” The question arises (and it’s impossible to answer): will our children – and, indeed, our grandchildren and great grandchildren – think we made a good job of spending their inheritance? In the village where I live in leafy Lincolnshire, England’s oldest canal wends its way and, especially in summer, it hosts narrowboats, former freight carriers now converted into floating leisure-time habitations whose owners can move them every few days to a new location. One of the regular visitors has been named by its owners ‘The Kids’ Inheritance’. If this is what the EU is doing, we need to ensure it never sinks.

The coronavirus pandemic came out of nowhere. No, I don’t mean it didn’t have an origin; it clearly did, probably in or around Wuhan in China. Pointing a finger of blame doesn’t help anyone and every country has suffered the consequences. But it was unexpected. Its scale and spread shocked everyone and left the experts scratching their heads. For governments around the world, it presented a massive, unprecedented challenge. The global economy, bubbling along nicely, suddenly went over a cliff and politicians were obliged to find ways to save their countries’ industries and businesses, as well as the lives of their citizens. And what do panicking politicians do when facing an unexpected crisis? They throw money at it, of course, most of which has to be borrowed. It’s very difficult to assess exactly how much because the methods used are many and various. Mostly, they take the form of fiscal-easing measures and Germany, Italy and the UK have each announced more than 20% of their GDP in fiscal support, with France a short way behind with 17.5%.

European Commission president, Ursula von der Leyen, during the European Parliament’s plenary session on 27 May © European Commission

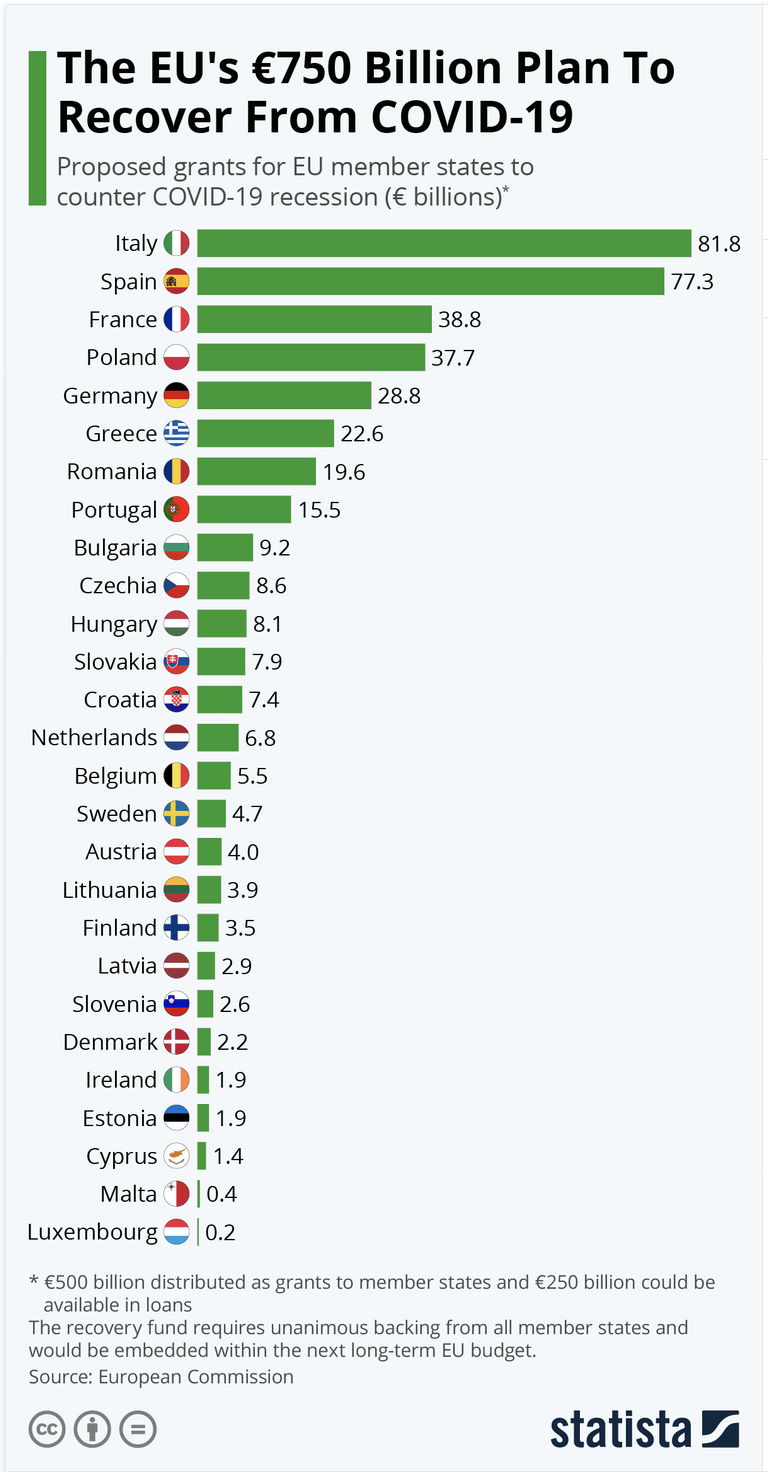

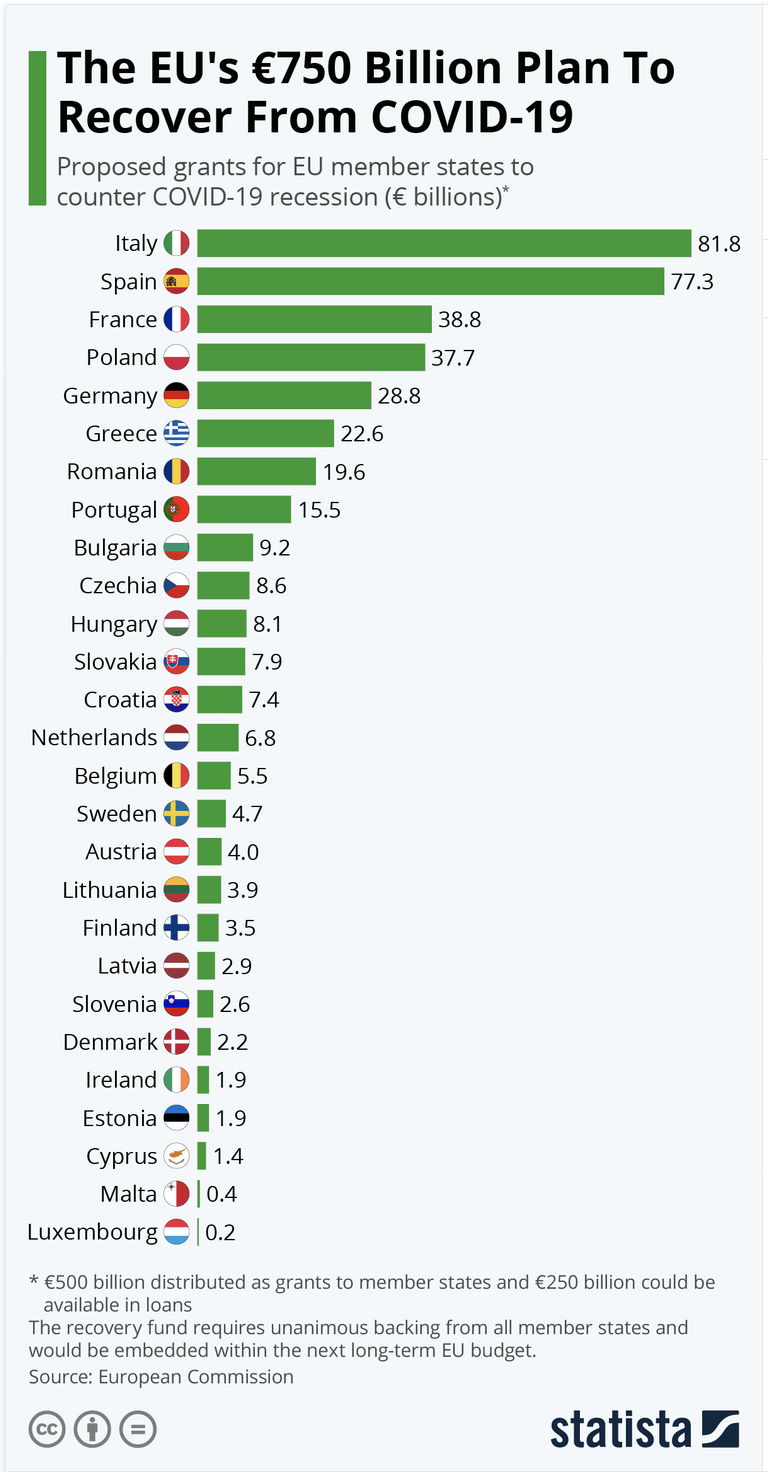

For the four largest eurozone economies – Germany, France, Italy and Spain, as well as for the UK – more than 70% of the total takes the form of government guarantees. Meanwhile the European Union proposed a stimulus package of €750-billion, which is equivalent to 6.3% of the GDP of the entire eurozone – the group of nineteen member states that use the euro as their currency.

The United States has put in place a massive stimulus package as well as a great many support instruments, with fiscal easing reaching 11.5% of GDP, higher than in Europe, while Japan exceeds all the others with various instruments – discretionary, quasi-fiscal and guarantees – reaching a staggering 32.3% of GDP, according to estimates by Fitch Ratings. One has to have confidence in the future to pledge so much on saving the present, although if you’re drowning far from land in shark-infested waters you don’t look too closely at who’s throwing the lifebelt or if it looks like a good one. The Federal Reserve in the US has pledged unlimited asset purchases and created fourteen new liquidity facilities. Fitch expects quantitative easing (QE) purchases to exceed $4-trillion (€3.57-trillion) in 2020.

European Commission president, Ursula von der Leyen, during the European Parliament’s plenary session on 27 May © European Commission

For the four largest eurozone economies – Germany, France, Italy and Spain, as well as for the UK – more than 70% of the total takes the form of government guarantees. Meanwhile the European Union proposed a stimulus package of €750-billion, which is equivalent to 6.3% of the GDP of the entire eurozone – the group of nineteen member states that use the euro as their currency.

The United States has put in place a massive stimulus package as well as a great many support instruments, with fiscal easing reaching 11.5% of GDP, higher than in Europe, while Japan exceeds all the others with various instruments – discretionary, quasi-fiscal and guarantees – reaching a staggering 32.3% of GDP, according to estimates by Fitch Ratings. One has to have confidence in the future to pledge so much on saving the present, although if you’re drowning far from land in shark-infested waters you don’t look too closely at who’s throwing the lifebelt or if it looks like a good one. The Federal Reserve in the US has pledged unlimited asset purchases and created fourteen new liquidity facilities. Fitch expects quantitative easing (QE) purchases to exceed $4-trillion (€3.57-trillion) in 2020.

The Bank of England in Threadneedle Street, London.

In Britain, the government has made available £100-billion (over €110-billion) to fund such measures in the form of job retention schemes – paying a proportion of the wages people would have earned if they had not been ‘furloughed’, effectively told to stay at home and to be idle. The UK has also made a further £330-billion (€365-billion) available through the coronavirus business interruption loan scheme and the Covid Corporate Financing Facility. In its largest ever emergency financial aid measure, the United States has pledged $2-trillion (€1.78-trillion), including $25-billion (€22.3-billion) in grants for airlines. In Europe, the Brussels-based Breughel think tank has explained the immediate first-aid measures governments have taken: “additional government spending (such as medical resources, keeping people employed, subsidising SMEs, public investment) and foregone revenues (such as the cancellation of certain taxes and social security contributions). These types of measures immediately lead to deterioration of the budget balance without any direct compensation later.”

DEBTS AND DEBTORS

As I said earlier, death and taxes; it’s what lies behind the Next Generation EU programme, also mentioned by von der Leyen in Rome. “We all understand that the recovery will be a generational challenge,” she said. But it’s Breughel that puts into figures the longer-term implications. “The incorporation of the temporary Next Generation EU into the EU’s next multiannual budget would take advantage of a well-established framework, already subject to various checks and balances. The temporary instrument would add €433-billion in grants, €67-billion in guarantees and €250-billion in loans (measured at 2018 prices) to the €1,100-billion ‘standard’ seven-year EU budget for 2021-2027. Considering the urgency of EU budget support, the Commission also proposed to add €11.5-billion (at current prices) to the current 2020 annual budget, of which €5-billion would be grants and €6.5-billion would be guarantees.” We are talking here in terms of figures most of us (myself included) probably struggle to grasp. But EU budgets are not spent overnight; they are slow moving affairs, which is why the Commission insisted that commitments under the new recovery instruments should be front-loaded, and according to Breughel, they are. “Commitments related to the combined €438-billion grant component of Next Generation EU and the 2020 annual budget amendment are indeed frontloaded: 78% of total commitments are scheduled to be agreed in 2020-2022. However, the Commission expects that barely 24.9% of the total new firepower for grants would be spent in 2020-2022, when the recovery needs will be greatest.” In other words, most of the money won’t be fully available at the time of greatest need and paying it back could take years. Borrowing from our children, indeed, not to mention their children and grandchildren, too.

The Bank of England in Threadneedle Street, London.

In Britain, the government has made available £100-billion (over €110-billion) to fund such measures in the form of job retention schemes – paying a proportion of the wages people would have earned if they had not been ‘furloughed’, effectively told to stay at home and to be idle. The UK has also made a further £330-billion (€365-billion) available through the coronavirus business interruption loan scheme and the Covid Corporate Financing Facility. In its largest ever emergency financial aid measure, the United States has pledged $2-trillion (€1.78-trillion), including $25-billion (€22.3-billion) in grants for airlines. In Europe, the Brussels-based Breughel think tank has explained the immediate first-aid measures governments have taken: “additional government spending (such as medical resources, keeping people employed, subsidising SMEs, public investment) and foregone revenues (such as the cancellation of certain taxes and social security contributions). These types of measures immediately lead to deterioration of the budget balance without any direct compensation later.”

DEBTS AND DEBTORS

As I said earlier, death and taxes; it’s what lies behind the Next Generation EU programme, also mentioned by von der Leyen in Rome. “We all understand that the recovery will be a generational challenge,” she said. But it’s Breughel that puts into figures the longer-term implications. “The incorporation of the temporary Next Generation EU into the EU’s next multiannual budget would take advantage of a well-established framework, already subject to various checks and balances. The temporary instrument would add €433-billion in grants, €67-billion in guarantees and €250-billion in loans (measured at 2018 prices) to the €1,100-billion ‘standard’ seven-year EU budget for 2021-2027. Considering the urgency of EU budget support, the Commission also proposed to add €11.5-billion (at current prices) to the current 2020 annual budget, of which €5-billion would be grants and €6.5-billion would be guarantees.” We are talking here in terms of figures most of us (myself included) probably struggle to grasp. But EU budgets are not spent overnight; they are slow moving affairs, which is why the Commission insisted that commitments under the new recovery instruments should be front-loaded, and according to Breughel, they are. “Commitments related to the combined €438-billion grant component of Next Generation EU and the 2020 annual budget amendment are indeed frontloaded: 78% of total commitments are scheduled to be agreed in 2020-2022. However, the Commission expects that barely 24.9% of the total new firepower for grants would be spent in 2020-2022, when the recovery needs will be greatest.” In other words, most of the money won’t be fully available at the time of greatest need and paying it back could take years. Borrowing from our children, indeed, not to mention their children and grandchildren, too.

The most detailed breakdown from a European perspective comes from a blog by Zsolt Darvas, again for Breughel, which is largely supportive. “Limited guidelines were provided however on the estimated overall cross-country allocation in the Commission’s two recent proposals: the €750-billion ‘Next Generation EU’ plan and the additional €11.2-billion amendment to the 2020 annual budget. Cross-countries allocation proposals have been published for only three out of the twelve different instruments that make up the package: the Recovery and Resilience Facility, the Just Transition Fund and agricultural subsidies. Guidance is vague for the other nine, which account for about a third of the grant and guarantee components. The Commission either provided the detailed methodology behind cross-country allocations without any estimate (REACT-EU); indicated broad principles for cross-country allocations (Solvency Support Instrument and Invest EU); or provided no guidelines for cross-country allocation.” REACT-EU stands for Recovery Assistance for Cohesion and the Territories of Europe, which comprises €50-billion in grants from ‘Next Generation EU’ and €4.8-billion in grants from the amended 2020 annual EU budget (Multiannual Financial Framework, or MFF).

The most detailed breakdown from a European perspective comes from a blog by Zsolt Darvas, again for Breughel, which is largely supportive. “Limited guidelines were provided however on the estimated overall cross-country allocation in the Commission’s two recent proposals: the €750-billion ‘Next Generation EU’ plan and the additional €11.2-billion amendment to the 2020 annual budget. Cross-countries allocation proposals have been published for only three out of the twelve different instruments that make up the package: the Recovery and Resilience Facility, the Just Transition Fund and agricultural subsidies. Guidance is vague for the other nine, which account for about a third of the grant and guarantee components. The Commission either provided the detailed methodology behind cross-country allocations without any estimate (REACT-EU); indicated broad principles for cross-country allocations (Solvency Support Instrument and Invest EU); or provided no guidelines for cross-country allocation.” REACT-EU stands for Recovery Assistance for Cohesion and the Territories of Europe, which comprises €50-billion in grants from ‘Next Generation EU’ and €4.8-billion in grants from the amended 2020 annual EU budget (Multiannual Financial Framework, or MFF).

Debate on the recovery plan and the EU’s long-term budget © European Paliament

All this largesse, which we really cannot afford yet cannot afford not to offer, comes at a price, like that huge credit card bill that drops through your door after an over-indulgent shopping spree or (and the comparison is perhaps closer) a costly and unlucky visit to a casino. In the UK, Prime Minister Boris Johnson is being obliged to break one of his party’s election pledges. He promised to retain the ‘triple lock’ on pensions, which is very important for his (largely elderly) supporters. Under it, the state pension goes up each year in line with the rising cost of living, as shown by the Consumer Price Index, the increase in average wages or by 2.5%, whichever is the greater. But the various emergency measures over Covid-19 mean that the UK can’t afford it. The piggy bank is not only empty but stuffed with hastily-scribbled IOUs. The UK Treasury believes that an increase in wages after the lockdown ends could put pensions up by 20% from April 2022, costing the taxpayer £20-billion (€22-billion). It leaves the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Rishi Sunak, who has not been long in the job, with a nasty choice: break the promise or break the economy. Treasury officials are referring to the dilemma, rather charmingly, as a ‘statistical anomaly’. When something has to yield, promises are, as the saying goes, like pie crusts: made to be broken.

Things are no better in the United States. By mid-June, the US Labor Department revealed that 1.5-million people had applied for unemployment benefits for the first time during the previous week. That makes thirteen successive weeks in which more than a million out-of-work Americans filed for unemployment benefit for the first time. A hole this deep requires a very long, strong ladder if you’re ever to climb out of it. There will be a second stimulus package. Congress hasn’t set a date for a vote on such a deal, but Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell said the Senate may wait till the end of July to start work on the bill, according to Bloomberg. What’s more, the second relief package may be the last. The Senate has scheduled a two-week recess before work begins on a second package, with the executive branch working on a programme of its own, according to White House officials. CNET writes that when the Senate, House and White House negotiators do begin negotiations, they’ll be under pressure to reach a deal quickly, because the enhanced unemployment allowances that provide an additional $600 (€534) per month are set to expire on July 31.

But the outlook is not entirely gloomy; there are some somewhat surprising signs of hope. While the Organisation of European Cooperation and Development (OECD), made up of mainly relatively well-off nations, was predicting long-lasting negative consequences from the coronavirus, US share prices were returning to almost the same levels they showed before it all began, with the stock market there seeing its greatest 50-day rally ever. European and Japanese markets are also performing exceptionally – and somewhat unexpectedly – well. Nobody is entirely sure why. Is it because of all the stimuli being provided by various governments? Or are there other factors at work? Despite the rise in unemployment cited by the US Labor Department, the rate fell during May, from 14.7% to 13.3%, which surprised those who expected it to rise to 20%. Yes, that’s good, but it still leaves some twenty-million workers without a job and there are still fears that when it’s all over the businesses that employed them may have gone, leaving them without a job to go back to. Those that succeeded because their workers found they could just as easily work from home will probably find their employers moving to smaller premises or doing away with the need for premises altogether. And, of course, we must not forget that the unemployment rate under the pandemic is still much higher than just after the financial crash of 2007-09.

Debate on the recovery plan and the EU’s long-term budget © European Paliament

All this largesse, which we really cannot afford yet cannot afford not to offer, comes at a price, like that huge credit card bill that drops through your door after an over-indulgent shopping spree or (and the comparison is perhaps closer) a costly and unlucky visit to a casino. In the UK, Prime Minister Boris Johnson is being obliged to break one of his party’s election pledges. He promised to retain the ‘triple lock’ on pensions, which is very important for his (largely elderly) supporters. Under it, the state pension goes up each year in line with the rising cost of living, as shown by the Consumer Price Index, the increase in average wages or by 2.5%, whichever is the greater. But the various emergency measures over Covid-19 mean that the UK can’t afford it. The piggy bank is not only empty but stuffed with hastily-scribbled IOUs. The UK Treasury believes that an increase in wages after the lockdown ends could put pensions up by 20% from April 2022, costing the taxpayer £20-billion (€22-billion). It leaves the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Rishi Sunak, who has not been long in the job, with a nasty choice: break the promise or break the economy. Treasury officials are referring to the dilemma, rather charmingly, as a ‘statistical anomaly’. When something has to yield, promises are, as the saying goes, like pie crusts: made to be broken.

Things are no better in the United States. By mid-June, the US Labor Department revealed that 1.5-million people had applied for unemployment benefits for the first time during the previous week. That makes thirteen successive weeks in which more than a million out-of-work Americans filed for unemployment benefit for the first time. A hole this deep requires a very long, strong ladder if you’re ever to climb out of it. There will be a second stimulus package. Congress hasn’t set a date for a vote on such a deal, but Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell said the Senate may wait till the end of July to start work on the bill, according to Bloomberg. What’s more, the second relief package may be the last. The Senate has scheduled a two-week recess before work begins on a second package, with the executive branch working on a programme of its own, according to White House officials. CNET writes that when the Senate, House and White House negotiators do begin negotiations, they’ll be under pressure to reach a deal quickly, because the enhanced unemployment allowances that provide an additional $600 (€534) per month are set to expire on July 31.

But the outlook is not entirely gloomy; there are some somewhat surprising signs of hope. While the Organisation of European Cooperation and Development (OECD), made up of mainly relatively well-off nations, was predicting long-lasting negative consequences from the coronavirus, US share prices were returning to almost the same levels they showed before it all began, with the stock market there seeing its greatest 50-day rally ever. European and Japanese markets are also performing exceptionally – and somewhat unexpectedly – well. Nobody is entirely sure why. Is it because of all the stimuli being provided by various governments? Or are there other factors at work? Despite the rise in unemployment cited by the US Labor Department, the rate fell during May, from 14.7% to 13.3%, which surprised those who expected it to rise to 20%. Yes, that’s good, but it still leaves some twenty-million workers without a job and there are still fears that when it’s all over the businesses that employed them may have gone, leaving them without a job to go back to. Those that succeeded because their workers found they could just as easily work from home will probably find their employers moving to smaller premises or doing away with the need for premises altogether. And, of course, we must not forget that the unemployment rate under the pandemic is still much higher than just after the financial crash of 2007-09.

Nikkei Building, located at Ōtemachi, Chiyoda, Tokyo, Japan © Wikicommons

BUY, BUY, LOVE

The drop in consumer spending caused by the closure of shops and other businesses has been compensated for by soaring on-line sales. Jeff Bezos is laughing all the way to the bank as would-be shoppers increasingly turn to Amazon, where roughly $11,000 (€9,840) worth of goods change hands every second. Bezos has quite a record. He tried and failed to buy out Netflix in 1998 and his interest in the remote television interviewing app, Zoom, which has been the mainstay of television news since the coronavirus pandemic began, was unsuccessful. Zoom’s founders chose to go with Oracle instead of Amazon Web Services (AWS) as its Cloud Infrastructure provider. Even so, Bezos can probably expect his business for 2020 to exceed the $280-billion (€250.51) it generated last year. No wonder its shares trade at 118 times its earnings, way ahead of what Apple and Microsoft achieve. Incidentally, Donald Trump doesn’t like him, which may boost his popularity among Amazon’s customers.

Nikkei Building, located at Ōtemachi, Chiyoda, Tokyo, Japan © Wikicommons

BUY, BUY, LOVE

The drop in consumer spending caused by the closure of shops and other businesses has been compensated for by soaring on-line sales. Jeff Bezos is laughing all the way to the bank as would-be shoppers increasingly turn to Amazon, where roughly $11,000 (€9,840) worth of goods change hands every second. Bezos has quite a record. He tried and failed to buy out Netflix in 1998 and his interest in the remote television interviewing app, Zoom, which has been the mainstay of television news since the coronavirus pandemic began, was unsuccessful. Zoom’s founders chose to go with Oracle instead of Amazon Web Services (AWS) as its Cloud Infrastructure provider. Even so, Bezos can probably expect his business for 2020 to exceed the $280-billion (€250.51) it generated last year. No wonder its shares trade at 118 times its earnings, way ahead of what Apple and Microsoft achieve. Incidentally, Donald Trump doesn’t like him, which may boost his popularity among Amazon’s customers.

Jeff Bezos founder, CEO, and president of the multi-national technology company Amazon © Wikicommons

Consumer spending in the US was at its lowest in April, just after lockdown began, but by early June it was back up to 90% of its pre-crisis level. And, just as consumer spending and stockmarkets have been enjoying a bit of a boom, so have the prices of some raw materials. According to The Economist, iron ore has increased in price from $80 (€71.24) a tonne to $100 (€89.06), while copper prices are also up by 25%. Again, the reasons are hard to pin down and may prove ephemeral. Partly it’s because China is buying raw materials and producing a lot of steel, which must please Australia, the world’s largest supplier of iron ore. Why? Again, it could be because China seems to have a Keynsian faith in constructing its way out of economic problems. As the Buttonwood column in The Economist suggests: “A pattern in markets is that a lot happens by rote. China’s response to a weak economy is to build; investors’ response to the Fed’s easing is to buy stocks; the algorithms’ response to a weaker dollar is to buy commodities. Higher prices beget higher prices. The sceptics, the too-sooners, note that this also works in reverse. Quite so. But the momentum is now with the believers.” Let’s all cheer on the believers.

The EU is putting its faith not in building things it doesn’t need (although Keynes might have thought that a good idea) but in huge shovelfuls of cash. The last General Affairs Council under the Croatian presidency saw massive support for the relief package. After the Council, held this time through a video conferencing facility, Commission President Ursula von der Leyen told the media that the ministers had backed the Commission’s line. “It is essential that we lose no time,” she said, “in setting our economic and social recovery on a firm footing and as you know, the Commission has come forward with a plan to do just that. It’s called Next Generation EU, combined with a reinforced MFF.” It’s something von der Leyen has often spoken about before: it’s the money she said we’re borrowing from our children. She clearly puts great faith in it. “It will provide the necessary means,” she told journalists, “the MFF of €1850-billion and the proper focus on a green, digital and resilient recovery to help the European Union, its citizens, its businesses, to emerge stronger from this crisis.”

It all adds to the debt now facing every country in the world. The Institute of International Finance says that global debt across all sectors rose by more than $10-trillion (€8.94-trillion) in 2019, ending up over $255-trillion (€227.89-trillion). It stands at more than 322% of GDP, 40 percentage points ($87-trillion or €77.75-trillion) higher than when the 2008 financial crisis began. What nobody seems to be talking about is how and when the massive debts will fall due for repayment. But then, they don’t really need to.

BEFORE THE BAILIFFS ARRIVE

In a blog for the London School of Economics, Carsten Jung says governments are right to cash in on the historically tiny interest rates to borrow as much as they need to stimulate the damaged economy. “The government can afford to increase its debt level, because interest rates are close to zero – the lowest they have ever been,” he writes. “This means that, even with more borrowing, only a limited share of annual tax revenues would need to be spent on servicing the debt each year. This is akin to a person taking out a mortgage – someone can afford a bigger mortgage if interest rates are low at 1% as opposed to when they are high at 5%. Therefore, as long as borrowing costs remain low, a high level of government debt remains affordable. In fact, interest rates are currently so low that even a doubling of the UK’s debt would still mean the Treasury pays less to service this debt, as a share of tax receipts, than any other time in the 20th century.” That’s as long as interest rates remain at this level, of course.

Jeff Bezos founder, CEO, and president of the multi-national technology company Amazon © Wikicommons

Consumer spending in the US was at its lowest in April, just after lockdown began, but by early June it was back up to 90% of its pre-crisis level. And, just as consumer spending and stockmarkets have been enjoying a bit of a boom, so have the prices of some raw materials. According to The Economist, iron ore has increased in price from $80 (€71.24) a tonne to $100 (€89.06), while copper prices are also up by 25%. Again, the reasons are hard to pin down and may prove ephemeral. Partly it’s because China is buying raw materials and producing a lot of steel, which must please Australia, the world’s largest supplier of iron ore. Why? Again, it could be because China seems to have a Keynsian faith in constructing its way out of economic problems. As the Buttonwood column in The Economist suggests: “A pattern in markets is that a lot happens by rote. China’s response to a weak economy is to build; investors’ response to the Fed’s easing is to buy stocks; the algorithms’ response to a weaker dollar is to buy commodities. Higher prices beget higher prices. The sceptics, the too-sooners, note that this also works in reverse. Quite so. But the momentum is now with the believers.” Let’s all cheer on the believers.

The EU is putting its faith not in building things it doesn’t need (although Keynes might have thought that a good idea) but in huge shovelfuls of cash. The last General Affairs Council under the Croatian presidency saw massive support for the relief package. After the Council, held this time through a video conferencing facility, Commission President Ursula von der Leyen told the media that the ministers had backed the Commission’s line. “It is essential that we lose no time,” she said, “in setting our economic and social recovery on a firm footing and as you know, the Commission has come forward with a plan to do just that. It’s called Next Generation EU, combined with a reinforced MFF.” It’s something von der Leyen has often spoken about before: it’s the money she said we’re borrowing from our children. She clearly puts great faith in it. “It will provide the necessary means,” she told journalists, “the MFF of €1850-billion and the proper focus on a green, digital and resilient recovery to help the European Union, its citizens, its businesses, to emerge stronger from this crisis.”

It all adds to the debt now facing every country in the world. The Institute of International Finance says that global debt across all sectors rose by more than $10-trillion (€8.94-trillion) in 2019, ending up over $255-trillion (€227.89-trillion). It stands at more than 322% of GDP, 40 percentage points ($87-trillion or €77.75-trillion) higher than when the 2008 financial crisis began. What nobody seems to be talking about is how and when the massive debts will fall due for repayment. But then, they don’t really need to.

BEFORE THE BAILIFFS ARRIVE

In a blog for the London School of Economics, Carsten Jung says governments are right to cash in on the historically tiny interest rates to borrow as much as they need to stimulate the damaged economy. “The government can afford to increase its debt level, because interest rates are close to zero – the lowest they have ever been,” he writes. “This means that, even with more borrowing, only a limited share of annual tax revenues would need to be spent on servicing the debt each year. This is akin to a person taking out a mortgage – someone can afford a bigger mortgage if interest rates are low at 1% as opposed to when they are high at 5%. Therefore, as long as borrowing costs remain low, a high level of government debt remains affordable. In fact, interest rates are currently so low that even a doubling of the UK’s debt would still mean the Treasury pays less to service this debt, as a share of tax receipts, than any other time in the 20th century.” That’s as long as interest rates remain at this level, of course.

Thomas Piketty, Director of Studies at L’École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales and Professor at the Paris School of Economics © Wikipedia

Thomas Piketty, the world’s best-selling economist, who is also Director of Studies at L’École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales and Professor at the Paris School of Economics, says we shouldn’t worry. In his latest book, ‘Capital and Ideology’, he dismisses those who talked up the huge debts that accumulated during the eurozone crisis. “All these enlightened pundits appeared to be almost totally ignorant of the history of public debt,” he writes, “not least the fact that debt had been cancelled many times over the centuries and particularly in the twentieth century, often with success.” He goes on to explain. “Debt in excess of 200% of GDP weighed on any number of countries in 1945-50, including Germany, Japan, France and most other countries of Europe, yet it was eliminated within a few years by a combination of one-time taxes on private capital, outright repudiation, rescheduling, and inflation. Europe was built in the 1950s by wiping away past debt, thereby allowing countries to turn their attention to the younger generation and invest in the future.” Piketty admits, though, that debt and repayment are complex issues and much more complicated than populist movements would have us believe. “To be sure, the leaders of Lega and M5S in Italy and of the ‘yellow vests’ in France who have called for referenda on debt cancellation may not fully appreciate the complexity of the issue, which cannot be settled by a simple ‘yes’ or ‘no’.” I must quote a little more from Piketty’s massive volume here, because it’s oddly pertinent to an issue that didn’t exist when he was writing it. “There is an urgent need for debate on the fiscal, financial, and institutional arrangements necessary to reschedule debt because it is ‘details’ like these that determine whether debt reduction comes at the expense of the wealthy (by way of a progressive wealth tax, for example) or of the poor (by way of inflation).” Piketty, not surprisingly for a left-leaning economist, tends to favour the former solution: let the wealthy pay for it. But even right-wing economists are critical of left wing groups who whinge about the debt. These sorts of debts don’t get repaid and never have. It’s like the old joke: if you owe your bank a thousand euros, it’s your problem; if you owe it several millions, it’s the bank’s. And everyone will owe everyone else, when the coronavirus pandemic comes to its end.

Thomas Piketty, Director of Studies at L’École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales and Professor at the Paris School of Economics © Wikipedia

Thomas Piketty, the world’s best-selling economist, who is also Director of Studies at L’École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales and Professor at the Paris School of Economics, says we shouldn’t worry. In his latest book, ‘Capital and Ideology’, he dismisses those who talked up the huge debts that accumulated during the eurozone crisis. “All these enlightened pundits appeared to be almost totally ignorant of the history of public debt,” he writes, “not least the fact that debt had been cancelled many times over the centuries and particularly in the twentieth century, often with success.” He goes on to explain. “Debt in excess of 200% of GDP weighed on any number of countries in 1945-50, including Germany, Japan, France and most other countries of Europe, yet it was eliminated within a few years by a combination of one-time taxes on private capital, outright repudiation, rescheduling, and inflation. Europe was built in the 1950s by wiping away past debt, thereby allowing countries to turn their attention to the younger generation and invest in the future.” Piketty admits, though, that debt and repayment are complex issues and much more complicated than populist movements would have us believe. “To be sure, the leaders of Lega and M5S in Italy and of the ‘yellow vests’ in France who have called for referenda on debt cancellation may not fully appreciate the complexity of the issue, which cannot be settled by a simple ‘yes’ or ‘no’.” I must quote a little more from Piketty’s massive volume here, because it’s oddly pertinent to an issue that didn’t exist when he was writing it. “There is an urgent need for debate on the fiscal, financial, and institutional arrangements necessary to reschedule debt because it is ‘details’ like these that determine whether debt reduction comes at the expense of the wealthy (by way of a progressive wealth tax, for example) or of the poor (by way of inflation).” Piketty, not surprisingly for a left-leaning economist, tends to favour the former solution: let the wealthy pay for it. But even right-wing economists are critical of left wing groups who whinge about the debt. These sorts of debts don’t get repaid and never have. It’s like the old joke: if you owe your bank a thousand euros, it’s your problem; if you owe it several millions, it’s the bank’s. And everyone will owe everyone else, when the coronavirus pandemic comes to its end.

Richard Murphy, Director of Tax Research UK © Taxresearch.org.uk

But it really doesn’t matter a jot, says Richard Murphy of Tax Research UK. “As a matter of fact we have repaid almost none of our national debt over the last 74 years. So why does anyone think we should start doing so now?” he asks. “And there are £71-billion of bank notes in circulation and a bit less than £5 billion in coins. These are all part of the national debt – the notes even have the fact printed on them. Why do we want to get rid of all these, which we would if we repaid the national debt?” So there you go: governments seldom rush to repay debts because they don’t have to. The UK government still has some undated war bonds (bonds with no maturity date) from the First World War. Those who bought them are hardly likely now to go hammering on the doors of the Treasury to get paid (although it would certainly shake Treasury officials if they did).

Even so, talk of simply keeping the massive debt on the books and never paying it back is unrealistic, however much paper the various central banks buy to calm things down and keep rates low. Carsten Jung again: “With a moderate debt level, this can work. But with a high debt level, it can be a problem. It would mean that the central bank will effectively be forced to make sure borrowing costs remain low, constantly. This is not a great place to be in, because when the economy recovers – and interest rates should be starting to rise – the central bank would be forced to keep rates low regardless. Artificially low rates can be bad for parts of the economy, cause financial bubbles and lead to too high inflation. In the long term, debt levels should be brought to a level that avoids such a catch 22 situation.” Remember, allowing high inflation to take hold means the burden of the debt will be borne disproportionately by the poor.

Every country, just about, is at it. In the UK, the total debt level has gone up by £173-billion (€191.15-billion) in the last year to £195-trillion (€215.46-trillion), or more than 100% of GDP. It’s the first time Britain’s public debt has exceeded the size of the country’s entire economy since 1963, the year of the Profumo Affair – when the then Minister of War, John Profumo, was found to have had an affair with Christine Keeler, a young model, at a time when she was also having an affair with a KGB official at the Soviet Embassy.

Richard Murphy, Director of Tax Research UK © Taxresearch.org.uk

But it really doesn’t matter a jot, says Richard Murphy of Tax Research UK. “As a matter of fact we have repaid almost none of our national debt over the last 74 years. So why does anyone think we should start doing so now?” he asks. “And there are £71-billion of bank notes in circulation and a bit less than £5 billion in coins. These are all part of the national debt – the notes even have the fact printed on them. Why do we want to get rid of all these, which we would if we repaid the national debt?” So there you go: governments seldom rush to repay debts because they don’t have to. The UK government still has some undated war bonds (bonds with no maturity date) from the First World War. Those who bought them are hardly likely now to go hammering on the doors of the Treasury to get paid (although it would certainly shake Treasury officials if they did).

Even so, talk of simply keeping the massive debt on the books and never paying it back is unrealistic, however much paper the various central banks buy to calm things down and keep rates low. Carsten Jung again: “With a moderate debt level, this can work. But with a high debt level, it can be a problem. It would mean that the central bank will effectively be forced to make sure borrowing costs remain low, constantly. This is not a great place to be in, because when the economy recovers – and interest rates should be starting to rise – the central bank would be forced to keep rates low regardless. Artificially low rates can be bad for parts of the economy, cause financial bubbles and lead to too high inflation. In the long term, debt levels should be brought to a level that avoids such a catch 22 situation.” Remember, allowing high inflation to take hold means the burden of the debt will be borne disproportionately by the poor.

Every country, just about, is at it. In the UK, the total debt level has gone up by £173-billion (€191.15-billion) in the last year to £195-trillion (€215.46-trillion), or more than 100% of GDP. It’s the first time Britain’s public debt has exceeded the size of the country’s entire economy since 1963, the year of the Profumo Affair – when the then Minister of War, John Profumo, was found to have had an affair with Christine Keeler, a young model, at a time when she was also having an affair with a KGB official at the Soviet Embassy.

John Profumo, former British Secretary of State for War

Keeler and fellow-model Mandy Rice Davies ended up in court (somewhat unfairly) and the man who had introduced them to Profumo, osteopath Stephen Ward, died in prison in what was passed off as a suicide but may not have been. The Conservative government of Prime Minister Harold MacMillan collapsed, ushering in the government of Labour’s Harold Wilson. Mr. Profumo took the fall for what was in fact fairly widespread naughtiness by ministers and the rich and powerful of the time; thus the sixties began with a sex scandal and continued with scandalous amounts of sex. Keeler always said Profumo was a kind and considerate lover, his wife stood by him, and he spent the rest of his life doing good work among the urban poor. The Profumo Affair fascinated the British public, however; titillation is always more interesting than politics and economics.

LARGESSE AND GENEROSITY

When it comes to stimulation packages, the five most generous countries in the G20 group are the United States, with $2.3-trillion (€2.03-trillion) or 11% of GDP; Germany with $189.3-billion (€168.77-billion or 4.9% of GDP); China, with a fairly modest-sounding $169.7-billion (€151.3-billion, just 1.2% of GDP); Canada, providing $145.4-billion (€129.63-billion), which is 8.4% of GDP; and Australia with $133.5-billion (€119.02-billion), or 9.7% of GDP. Meanwhile the European Central Bank has promised to spend over a trillion euros on buying Eurozone bonds over the next nine months. China Global Television Network (CGTN) points out that although the amount being doled out this time is greater, we have all been here before. “The United States used a stimulus package during the global recession a decade ago,” it reminds us.

“A $168-billion (€149.68-billion) stimulus named the Economic Stimulus Act of 2008, which mainly provides tax rebates to low and middle income Americans, was signed then by President George W. Bush in February 2008, aiming to increase employment and boost the U.S. economy.” President Bush wasn’t alone, either. “China pumped 4-trillion yuan (about $565-billion or €503.7-billion) as a stimulus package in late 2008 to lift its export-oriented economy under the impact of global financial crisis. The country’s GDP rose by 10.4 percent in 2010 from 8.7 percent in 2009. But that plan also caused the hidden problem of overcapacity.” That’s a timely reminder that huge financial stimulus packages are a somewhat blunt instrument and hard to target precisely. Give too much leeway to a nation’s bankers and anything can happen, as Joseph Stiglitz, the Nobel Prize-winning economist, pointed out in his book on the financial crisis of a decade ago, caused by greed and an unregulated trade in derivatives. “Bankers are (for the most part) not born any greedier than other people,” he wrote in ‘Freefall’, “It is just that they may have more opportunity and stronger incentives to do mischief at others’ expense. When private rewards are well aligned with social objectives, things work well; when they are not, matters can get ugly.” And they did.

John Profumo, former British Secretary of State for War

Keeler and fellow-model Mandy Rice Davies ended up in court (somewhat unfairly) and the man who had introduced them to Profumo, osteopath Stephen Ward, died in prison in what was passed off as a suicide but may not have been. The Conservative government of Prime Minister Harold MacMillan collapsed, ushering in the government of Labour’s Harold Wilson. Mr. Profumo took the fall for what was in fact fairly widespread naughtiness by ministers and the rich and powerful of the time; thus the sixties began with a sex scandal and continued with scandalous amounts of sex. Keeler always said Profumo was a kind and considerate lover, his wife stood by him, and he spent the rest of his life doing good work among the urban poor. The Profumo Affair fascinated the British public, however; titillation is always more interesting than politics and economics.

LARGESSE AND GENEROSITY

When it comes to stimulation packages, the five most generous countries in the G20 group are the United States, with $2.3-trillion (€2.03-trillion) or 11% of GDP; Germany with $189.3-billion (€168.77-billion or 4.9% of GDP); China, with a fairly modest-sounding $169.7-billion (€151.3-billion, just 1.2% of GDP); Canada, providing $145.4-billion (€129.63-billion), which is 8.4% of GDP; and Australia with $133.5-billion (€119.02-billion), or 9.7% of GDP. Meanwhile the European Central Bank has promised to spend over a trillion euros on buying Eurozone bonds over the next nine months. China Global Television Network (CGTN) points out that although the amount being doled out this time is greater, we have all been here before. “The United States used a stimulus package during the global recession a decade ago,” it reminds us.

“A $168-billion (€149.68-billion) stimulus named the Economic Stimulus Act of 2008, which mainly provides tax rebates to low and middle income Americans, was signed then by President George W. Bush in February 2008, aiming to increase employment and boost the U.S. economy.” President Bush wasn’t alone, either. “China pumped 4-trillion yuan (about $565-billion or €503.7-billion) as a stimulus package in late 2008 to lift its export-oriented economy under the impact of global financial crisis. The country’s GDP rose by 10.4 percent in 2010 from 8.7 percent in 2009. But that plan also caused the hidden problem of overcapacity.” That’s a timely reminder that huge financial stimulus packages are a somewhat blunt instrument and hard to target precisely. Give too much leeway to a nation’s bankers and anything can happen, as Joseph Stiglitz, the Nobel Prize-winning economist, pointed out in his book on the financial crisis of a decade ago, caused by greed and an unregulated trade in derivatives. “Bankers are (for the most part) not born any greedier than other people,” he wrote in ‘Freefall’, “It is just that they may have more opportunity and stronger incentives to do mischief at others’ expense. When private rewards are well aligned with social objectives, things work well; when they are not, matters can get ugly.” And they did.

President George W. Bush signing the Economic Stimulus Act of 2008 © White House

But it’s not just bankers we should fear. The pandemic will permanently change the world order, according to some experts. Governments that have seized powers to cope with the pandemic may be reluctant to surrender them afterwards: it’s handy to have your population under your control. Writing on the FP web page, Stephen M. Walt, the Robert Renée Belfer professor of international relations at Harvard University warned that “COVID-19 will create a world that is less open, less prosperous, and less free. It did not have to be this way, but the combination of a deadly virus, inadequate planning, and incompetent leadership has placed humanity on a new and worrisome path.” Robin Niblett, the director and chief executive of the UK’s Chatham House think tank, otherwise known as the Royal Institute of International Affairs, is even gloomier about our post-virus prospects: “It seems highly unlikely in this context that the world will return to the idea of mutually beneficial globalization that defined the early 21st century. And without the incentive to protect the shared gains from global economic integration, the architecture of global economic governance established in the 20th century will quickly atrophy. It will then take enormous self-discipline for political leaders to sustain international cooperation and not retreat into overt geopolitical competition.”

President George W. Bush signing the Economic Stimulus Act of 2008 © White House

But it’s not just bankers we should fear. The pandemic will permanently change the world order, according to some experts. Governments that have seized powers to cope with the pandemic may be reluctant to surrender them afterwards: it’s handy to have your population under your control. Writing on the FP web page, Stephen M. Walt, the Robert Renée Belfer professor of international relations at Harvard University warned that “COVID-19 will create a world that is less open, less prosperous, and less free. It did not have to be this way, but the combination of a deadly virus, inadequate planning, and incompetent leadership has placed humanity on a new and worrisome path.” Robin Niblett, the director and chief executive of the UK’s Chatham House think tank, otherwise known as the Royal Institute of International Affairs, is even gloomier about our post-virus prospects: “It seems highly unlikely in this context that the world will return to the idea of mutually beneficial globalization that defined the early 21st century. And without the incentive to protect the shared gains from global economic integration, the architecture of global economic governance established in the 20th century will quickly atrophy. It will then take enormous self-discipline for political leaders to sustain international cooperation and not retreat into overt geopolitical competition.”

Robin Niblett, director and chief executive of Chatham House © Chatam House

This pandemic has been the big disruptor: as big as a major war, more destructive than a major recession (although it will cause one). Countries may never be as co-operative with one another again. In a crisis, there’s no place like home, and people and countries may turn inwards to seek their salvations among their own kind. High streets will lose forever some of the familiar shops and businesses, travel – especially international travel – will be undertaken more reluctantly and warily. Will we ever feel safe among crowds, especially foreign crowds? Yes, probably; people are surprisingly quick at getting used to things. But it won’t be the same. Office workers now working from home will still be in contact through their computers, but they won’t be gathering around the coffee machine or water cooler, so conversations will be more pre-planned and less spontaneous; there will be less gossip. How that will affect relationships and ‘team spirit’ is something for tomorrow’s psychologists to mull over and enable them to write endless learned books about it. The fact is, most human beings don’t function well alone; we are a tribal creature by nature and calls to suicide prevention hotlines have dramatically increased during lockdown. It could produce a peculiar dichotomy in which people feel ill at ease alone, but also when surrounded by people. In the UK, Foreign Secretary Dominic Raab has said that when the UK does begin to come out of lockdown, people will be moving into a “new normal”, rather than returning to their pre-pandemic lives. Be prepared for shocks. Indeed, hundreds of former prime ministers, presidents, Nobel laureates and lawmakers have sent an open letter, organised by the Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance, based in Stockholm, are warning of governments becoming increasingly authoritarian. “Even some democratically elected governments are fighting the pandemic by amassing emergency powers that restrict human rights and enhance state surveillance without regard to legal restraints (or) Parliamentary oversight,” the letter warns. We may find there are worse things out there than a virus once the pandemic ends, such as repressive ideologies and people willing to uphold them by force. And no amount of hand washing or vaccine will get rid of them.

T. Kingsley Brooks

Robin Niblett, director and chief executive of Chatham House © Chatam House

This pandemic has been the big disruptor: as big as a major war, more destructive than a major recession (although it will cause one). Countries may never be as co-operative with one another again. In a crisis, there’s no place like home, and people and countries may turn inwards to seek their salvations among their own kind. High streets will lose forever some of the familiar shops and businesses, travel – especially international travel – will be undertaken more reluctantly and warily. Will we ever feel safe among crowds, especially foreign crowds? Yes, probably; people are surprisingly quick at getting used to things. But it won’t be the same. Office workers now working from home will still be in contact through their computers, but they won’t be gathering around the coffee machine or water cooler, so conversations will be more pre-planned and less spontaneous; there will be less gossip. How that will affect relationships and ‘team spirit’ is something for tomorrow’s psychologists to mull over and enable them to write endless learned books about it. The fact is, most human beings don’t function well alone; we are a tribal creature by nature and calls to suicide prevention hotlines have dramatically increased during lockdown. It could produce a peculiar dichotomy in which people feel ill at ease alone, but also when surrounded by people. In the UK, Foreign Secretary Dominic Raab has said that when the UK does begin to come out of lockdown, people will be moving into a “new normal”, rather than returning to their pre-pandemic lives. Be prepared for shocks. Indeed, hundreds of former prime ministers, presidents, Nobel laureates and lawmakers have sent an open letter, organised by the Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance, based in Stockholm, are warning of governments becoming increasingly authoritarian. “Even some democratically elected governments are fighting the pandemic by amassing emergency powers that restrict human rights and enhance state surveillance without regard to legal restraints (or) Parliamentary oversight,” the letter warns. We may find there are worse things out there than a virus once the pandemic ends, such as repressive ideologies and people willing to uphold them by force. And no amount of hand washing or vaccine will get rid of them.

T. Kingsley Brooks

Click

here to read the 2020 July edition of Europe Diplomatic Magazine

Kingsley Brooks

The most detailed breakdown from a European perspective comes from a blog by Zsolt Darvas, again for Breughel, which is largely supportive. “Limited guidelines were provided however on the estimated overall cross-country allocation in the Commission’s two recent proposals: the €750-billion ‘Next Generation EU’ plan and the additional €11.2-billion amendment to the 2020 annual budget. Cross-countries allocation proposals have been published for only three out of the twelve different instruments that make up the package: the Recovery and Resilience Facility, the Just Transition Fund and agricultural subsidies. Guidance is vague for the other nine, which account for about a third of the grant and guarantee components. The Commission either provided the detailed methodology behind cross-country allocations without any estimate (REACT-EU); indicated broad principles for cross-country allocations (Solvency Support Instrument and Invest EU); or provided no guidelines for cross-country allocation.” REACT-EU stands for Recovery Assistance for Cohesion and the Territories of Europe, which comprises €50-billion in grants from ‘Next Generation EU’ and €4.8-billion in grants from the amended 2020 annual EU budget (Multiannual Financial Framework, or MFF).

The most detailed breakdown from a European perspective comes from a blog by Zsolt Darvas, again for Breughel, which is largely supportive. “Limited guidelines were provided however on the estimated overall cross-country allocation in the Commission’s two recent proposals: the €750-billion ‘Next Generation EU’ plan and the additional €11.2-billion amendment to the 2020 annual budget. Cross-countries allocation proposals have been published for only three out of the twelve different instruments that make up the package: the Recovery and Resilience Facility, the Just Transition Fund and agricultural subsidies. Guidance is vague for the other nine, which account for about a third of the grant and guarantee components. The Commission either provided the detailed methodology behind cross-country allocations without any estimate (REACT-EU); indicated broad principles for cross-country allocations (Solvency Support Instrument and Invest EU); or provided no guidelines for cross-country allocation.” REACT-EU stands for Recovery Assistance for Cohesion and the Territories of Europe, which comprises €50-billion in grants from ‘Next Generation EU’ and €4.8-billion in grants from the amended 2020 annual EU budget (Multiannual Financial Framework, or MFF).