“Meat without slaughter” is the motto of Cell Agritech, a Malaysian company creating meat using biotechnology, by growing it directly from animal cells © Cell-agritech

I became a vegetarian many years ago after filming a news report at a vary large abattoir. I shall not name it, because not everyone will share my revulsion at what I saw, but I haven’t touched meat since. I was with a cameraman (who still eats meat, as far as I know) in the main room where the slaughtering takes place, surrounded by a large number of understandably nervous-looking and somewhat noisy young cattle, who were about to meet their maker, or possibly a chef. The entire operation was overseen by a veterinarian expert who checked that the creatures were (or had been prior to death) healthy. At one point, the severed head of a newly-slaughtered young bull was taken away for examination in another room and shortly afterwards was brought back to show to the slaughterman himself. The vet or one of his minions held it up for all to see. It was, of course, no longer attached to the body and the skin covering it had been removed, effectively peeled away, so it was not a pretty sight. However – and this was what troubled me – there was still a detectable and quite prominent pulse in its neck. I saw that, which must be something that occurs every day, and I vowed there and then never to eat meat ever again, and I haven’t. I must be the bane of my poor wife’s life! She copes extremely well, of course, producing delicious but meat-free meals.

It’s now just over a decade since the world was first introduced to what’s become known as “lab-grown meat”. It happened at Maastricht University in the Netherlands and the fake meat thus produced was then consumed at a press conference in London, where it met a mixed reception, although everyone who tasted it – including those who didn’t like it much – believed it would have a bright future. The aim of creating cell-cultured meat was not to help vegetarians like me find easier alternatives, it was simply to reduce the need to farm animals so that feeding the fast-growing population wouldn’t take up so much land. It could help deal with the climate crisis, too, although the fake meat thus produced must not only be tasty and adaptable, it must also meet the widely varying food standards that are in place, even across the European Union. And it must taste like real meat, of course, and yield to the tender skills of a large number of chefs, as well as being tasty.

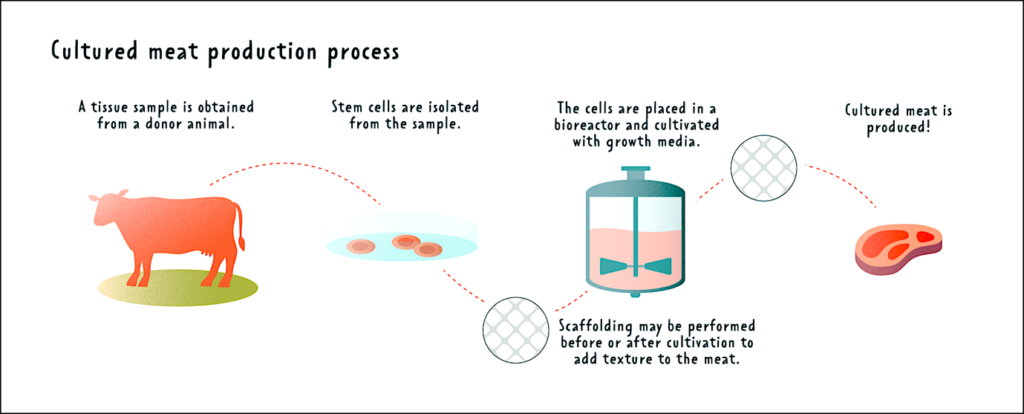

Since meat is produced without manufacturing anything, but rather by feeding animals we seem to have evolved to eat, just what exactly is cell-cultured meat, or simply “cultured meat”, as it’s often called? It’s not legal to refer to the product as “meat” or “beef” in the United States because of action by the National Cattlemen’s Association (yes, the days of Rawhide and six-guns live on), although some of the resulting cultures are produced by reproducing animal protein. The US Department of Agriculture has also given the green light to sales of lab-produced meat, even if it has to bear an appropriate label. The desire to achieve a “meat-free” meat market is partly driven by concern over the environmental cost of real meat production, in terms of the consumption of resources and the releases of greenhouse gasses. So, in biological terms, “cultured meat” is identical to meat produced conventionally, even if no animals are killed in the process. Another driving factor is its value on global markets, although accurate labelling remains a major issue. However, in this case the starting point is with animal stem cells, which are harvested using what are described as “minimally invasive” measures. Cells are developed into muscle and fat cells in some kind of growth medium, in larger and larger bioreactors until they reach “optimal cell density.” They are then separated from growth medium, using centrifuges and finally, the cells are then processed, or else additives are combined to achieve such things as texture. The resulting texture depends on exactly what kind of “meat” the product is meant to imitate.

The market is developing, meanwhile. It was back in 2020 that cultured meat, produced in bioreactors, first went on sale in the UK, which was seen as quite a breakthrough. Needless to say, it’s far easier to raise a food animal in some way, through the normal processes of feeding and providing shelter, than to manufacture what tastes like one from scratch. Probably cheaper, too. But we’re looking ahead to a future that may be somewhat different. I have a personal attachment to cheese, especially French cheese, but I like English cheese, too, of course: nothing quite compares with a slice of blue Stilton. The nutty, creamy flavour of cheddar cheese varies according to a delicate balance of bacteria, according to Chen Ly, writing in the New Scientist magazine. Now, it seems, those bacteria have been identified. As its makers have long known, the flavours of various cheeses rely on the various bacteria, such as streptococcus thermophilus and various kinds of lactococcus, while it would seem that while lactocremoris appears to regulate the development of the chemicals diacetyl and acetoin, which apparently provide a buttery flavour but if overused can result in the cheese tasting “off”, according to Chen Ly in a January edition of New Scientist. Lactocremoris can also increase the concentrations of compounds that add “subtle meaty and fruity notes”. All cheeses begin with the addition of “starter cultures” to milk, which also adds an acidic note to give the cheese a tangy taste. The latest findings could help cheese makers to adjust their products in ways that give them a particular flavour. Can I offer to be the researchers’ taster, please?

| ANOTHER SLICE OF PEA, PLEASE

At present, the production and sale of cultured meats varies from country to country but is regulated in the EU under the Novel Foods regulation. Even so, the rapid growth in sales of lab-grown meat has been predicted: a report by the global consultancy company AT Kerney has claimed that by 2040 most meat would be produced that way, rather than from “dead animals”, as it put it. The current evidence doesn’t fully support that view. A worldwide survey of consumers for the vegan firm Strong Roots found that although 61% of consumers are increasing their consumption of plant-based foods, 40% are also reducing their use of fake meats, mainly because of flavour but also because of uncertainty about what chemicals they may contain. In fact, while the contents listed on packets of the stuff may be puzzling, they would seem to be fairly safe.

The latest packet of Cauldron vegetarian “Lincolnshire Sausages” my wife bought lists their contents like this: “rehydrated textured vegetable protein (45%),water, soya protein, potato starch, wheat gluten, stabiliser (dicalcium phosphate), water, onion, rapeseed oil, Lincolnshire seasoning (5%) yeast extract, salt, potassium chloride, herbs, fructose, white pepper, rusk, (made of wheat flour, salt, the raising agent ammonium bicarbonate), barley malt extract, carrot powder, leek powder, sage extract, nutmeg extract), dried free range egg white, soya protein, with methyl cellulose as the stabiliser. Such a list may not make many people’s mouths water but the finished product tastes very good.

Furthermore, any meat you eat doesn’t come with a list of ingredients. If it did, it might put you off eating it. Another product, under the interesting name: “This Isn’t Pork Sausages” contains a lot of “textured pea protein”, as well as such elements as rapeseed oil, xanthan gum and a variety of other substances, some of which (like methylcellulose, konjac and carrageenan) I must confess are unfamiliar to me. But I’m definitely going to plant some peas in my garden.

The raising of livestock for food carries a large environmental cost, of course. Additionally, there is growing public concern about the animals’ welfare. The demand for meat in its various forms leads to the slaughter of 130-million chickens every day, along with 4-million pigs.

According to Britain’s Guardian newspaper, 60% of the mammals that share this planet with us are livestock. By comparison, only 36% are human and a measly 4% are actually wild.

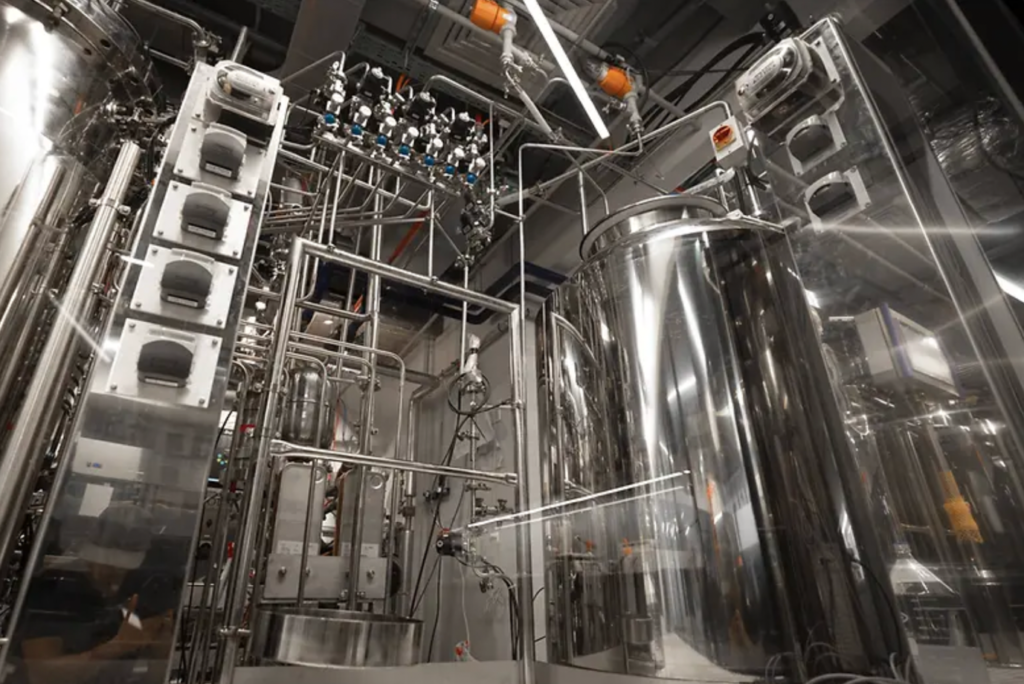

The company Eat Just grows its products in a 1,200-litre bioreactor and then mixes them with plant-based ingredients. Currently, it’s quite expensive to produce but a spokesperson for East Just has said that as demand and output increase, the cost will come down. Furthermore, we humans currently eat more meat than is good for us or our planet, so it’s time we looked again at our diet. Do we really need so much meat (or fish)? The brilliant pen-and-ink artist Frank Patterson who especially recorded the craze for cycling in all its forms once said that his idea of a “satisfying banquet”, as he put it, involved “tomatoes, bread and butter, cheese, a few apples and a pint of ale – two pints not coming amiss”. He reckoned it was even more satisfying if consumed in an old-fashioned pub of the type he so often drew. He ran a successful farm on just such a diet, too. A series of scientific studies have shown that people in wealthy nations eat more meat than is good for their health or for the good of the planet. Indeed, the Guardian reports that cutting down on the consumption of meat is not only vital for tackling the climate crisis but is also the best single environmental action an individual can take. It’s also safer because it avoids the risk of bacterial contamination that is present in real meat and the danger that whatever animals you’re consuming may have suffered an overuse of antibiotics and hormones. I can see and understand the dangers here but I also have a sneaking fear that without the need for animals to feed us, even if only with milk or eggs, our money-centric world would simply get rid of them, leaving us with a world of uninterrupted concrete. What a ghastly thought!

| BIG BUSINESS, BUT IS IT SUSTAINABLE?

Meanwhile, there has been growing demand for plant-based alternatives to meat, which was partly driven by the COVID lockdown as consumers around the world stayed at home, engaged in cooking and started to think seriously about the impact of their dietary choices on the planet as a whole. According to the research organisation GlobalData, the market value of the global meat substitutes reached $7-billion (€6.4-billion) in 2021, growing at a CAGR of 8.82% over the years from 2017 to 2021, and even faster in the United States. The increased demand also led to innovation on the part of manufacturers. Meati, a new entrant in the US food sector, for instance, announced two new chicken substitutes to be sold directly to consumers, with the chicken replacement in this case coming from fermented mycelium, part of the root structure of mushrooms. I’m inclined to think that fungi will play an increasingly important part in human dietary habits in the years ahead.

It’s been estimated that worldwide sales of meat substitutes will grow from $5.88-billion (€5.38-billion) in 2022 to $12.30-billion (€11.26-billion) by 2029, at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 11.11% in forecast period, 2022-2029. According to Fortune Business Insights, the arrival of the COVID pandemic raised doubts about the sustainability of meat production, obliging producers to seek viable alternatives. There is some doubt being expressed, however, about the long-term prospects for meat substitutes: we are a fickle bunch, we humans, and what seems like an attractive idea one day can be swept away the next, and there are faint signs that interest in alternatives to meat may be already beginning to fade. Healthy lifestyles have their appeal but it’s easier, perhaps, to go jogging or make trips to the gym than to give up your favourite burger and French fries or even your steak Diane, if you’re a little too sophisticated for burger and fries.

However, the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) has given the go-ahead to companies that want to start producing and selling cultivated chicken products in the United States. Lab-grown meat, also referred to as “cell-based” meat is based on real animal cells that have been fed nutrients and amino acids in factory-scale bioreactors, resulting in a product that should look like and – hopefully – taste like the animal from which the sample cells were obtained. I’m assured that the production facilities don’t look like a science laboratory, with test tubes, flasks and pipettes all over the place but rather more like a brewery, with large vats full of liquid. But the appeal of lab-grown meat is not likely to be its flavour primarily (although the kind I’ve been eating is very nice), it will be because it is less damaging to the environment. The resulting non-meat The idea is receiving a range of reactions: some countries (the Netherlands, for instance) is at the forefront of the non-meat revolution, with producers like Mosa Meat and Meatable pushing for EU regulatory approval, while in the United States, two companies backed by Bill Gates, namely Memphis Meats and New Age Meats, are doing much the same to win over regulators in Washington DC.

Needless to say, the whole idea has its detractors, nowhere more so than in Italy, where the government has completely banned lab-grown meat. Its agriculture minister, Francesco Lollobrigida of the far-right Brothers of Italy party (it doesn’t appear to include sisters) said: “Italy is the world’s first country safe from the social and economic risks of synthetic food.” It’s an odd claim, since there are, it seems, no such risks and the vote led to confrontations between those in favour of a ban and those equally strongly opposed. There was even a small fight. Those who want to see the development of more lab-grown meat were branded “criminals” and “hooligans”. Anyone who tries to produce non-meat meats faces a €60,000 fine. If the EU ever gives the go-ahead for lab-grown meat, it could lead to Italy’s new law being challenged. Meanwhile, Coldiretti, whose name stands for Confederazione Nazionale Coltivatori Diretti and which represents the interests of traditional farmers, has promised to continue efforts to retain the controversial ban, despite threats from animal welfare groups. The ban has also been condemned by Professor Elena Cattaneo, a life-long senator and leading bio-scientist, who dismissed the ban and the publicity surrounding it.

But despite the environmental and even animal welfare advantages of factory-produced meat, it is unlikely to replace normal meat in the very near future. For one thing, it’s more expensive to produce, although it uses far less land and much less water, although US experts have warned that it may involve greater energy consumption. According to the BBC, Cyrille Filott, the global strategist for Rabobank, the question is “how many boxes the lab grown product will tick for ‘early adopters’ to remain interested. ‘Taste, texture, price, sustainability, a long list of boxes. Will the novelty wear off or stick?” she wonders. It’s an interesting question but I suspect the answer lies in its potential for profit. Money drives everything in commerce, after all. If lab-grown meat proves profitable, it will succeed, accompanied by massive advertising campaigns to encourage us to consume it, in preference to traditional meat.

The global consultancy company AT Kearney has predicted that by 2040 more meat will come from factory production than from real animals. However, it’s thought likely that plant-based products (we’re getting back to peas again) are more likely to replace such processed “meat” products as burgers and sausages. A convincing steak Diane would be a challenge. The switch to lab-grown meats would be expensive, of course, requiring massive financial investment, which is unlikely to be forthcoming unless a substantial ready return can be confidently anticipated.

| PROS AND CONS

Extrusion technologies have long been used in food preparations. It involves mixing the required ingredients together and forcing them under high temperature through a small opening. It has been more commonly employed in the manufacture of pet foods, but it is also used for pie fillings and sausages. It ensures a regular, well mixed product that can then be shaped in a mould of some kind. Extrusion allows for the mass production of food through a continuous and efficient system that guarantees uniformity. Human foods produced that way include pasta, some kinds of bread, breakfast cereals, confectionary, biscuits of various types, baby food and so on. Of course, growing meat in a lab has its opponents, although their motives sometimes appear a little suspect. The University of California Davis and the University of California Holtville say that producing meat in a laboratory produces between four and twenty-five times as much carbon dioxide as raising cattle. Not every research company has reached the same conclusion, of course, while raising beef cattle is an important industry for California, which may have coloured opinions. But there have also been strong arguments against manufacturing meat in a laboratory. After all, if eating meat is bad for the environment, we could simply agree to eat less of it, rather than creating substitutes. Or we could agree to eat more vegetables instead.

There is another thing to take into consideration. It’s all very well for us folk in the wealthy countries to alter their diets for the sake of the environment, but what about the lives of the billion or so poor people around the world who depend on livestock for their livelihoods. Obviously they cannot switch to bioreactors and artificial means of producing meat, so presumably they and their families could simply starve. And recalling the interests and habits of developers, without animals grazing the fields, someone will soon be along with a lorry load of concrete and the architect’s drawings for a load of nearly identical bungalows. Only legal action of some kind can keep them away, it seems. Yes, I know we need homes for people. But must they be everywhere?

According to a report on lab-grown meat produced for Oxford University, replacing cattle with cultured meat may not be a simple swap. The report, under the Livestock, Environment, and People (LEAP) programme concludes that lab-grown meat cannot be seen as a cure-all for the damaging climate impacts of meat production, unless it’s part of a large-scale transition to decarbonised energy. Greenhouse gas emissions from raising animals for meat account for some 25% of global warming. But not all greenhouse gases, the report continues, generate the same degree of impact nor last as long in the atmosphere. The report was co-written by Raymond Pierrehumbert, Halley Professor of Physics at Oxford. “Cattle are very emissions-intensive,” he writes, “because they produce a large amount of methane from fermentation in their gut. “Methane is an important greenhouse gas,” he continues, “but the way in which we generally describe methane emissions as ‘carbon dioxide equivalent’ amounts can be misleading because the two gases are very different.” One of the main and most worrying differences is that although methane has a greater effect in terms of warming the atmosphere, its effects are comparably much shorter-lived, lasting for just twelve years, while “carbon dioxide persists and accumulates for millennia”.

The report, rather worryingly, concludes that if the effects of methane release over the next millennium are taken into account, it’s a very mixed picture. Perhaps if we all became vegetarians the problem might – I only say ‘might’ – be resolved. But that very clearly isn’t going to happen. We have to take into account the need for increasing areas of grazing land, which would inevitably mean few trees and forests, which would in turn be damaging.

The report’s conclusions are, at best, ambivalent, and the ultimate outcome may depend on the discovery of a sustainable low-carbon source of energy, which would make what’s being called “labriculture” more viable in the long term. Meanwhile, as research continues, I shall just continue to eat my vegetarian no-meat meals and enjoy them, relying on my wife’s considerable culinary skills!