What is the future of Europe? Can it be conceived? And who will lead us there? These questions were uppermost in my mind as I sat down to listen to a scheduled debate on where Europe is going from here. It was part of a long discussion, widely publicised in advance, featuring representatives of the European Parliament, the Council, the Commission, various governments and civil society, among a great many others. By the time it ended I was no longer certain that Europe has a future, such was the range of incompatible and opposing opinions about the options that lie ahead. I tried to find the antonym for serendipity, but there isn’t one. Not really, although misfortune, calamity, cataclysm and doom have been suggested, rather bleakly.

They’re not exactly the opposite of finding good fortune by accident and without intent, though the writer William Boyd, in his 1998 book Armadillo, suggested zamblanity for that purpose, but apart from cropping up in a court judgement in Ireland during a summing up by Mr Justice Michael Peart in 2012, the word has not found widespread usage or popularity. But as the saying goes, Romae non fuit dies (Rome was not built in a day). Actually, it’s an old French saying, so perhaps I should quote it in its original form: “Rome ne fu[t] pas faite toute en un jour”.

So how can we describe a successful grouping together of different nations for their mutual benefit?

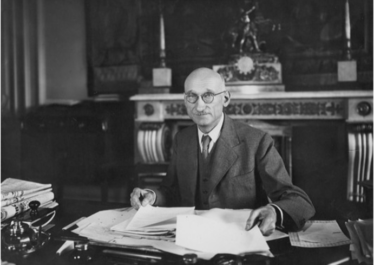

As far as the founders of the European Coal and Steel Community, grandfather of the European Union, were concerned, their great plan blossomed and bloomed, despite setbacks a-plenty along the way. Serendipity, one could argue, for John Monnet and Robert Schuman, perhaps; their aim (and that of colleagues like Dirk Spierenburg, Albert Coppé and Paul Finet) had been a union binding energy generation and the production of steel so as to prevent future wars. The Second World War had only just ended.

What came out of their deliberations went on to become the European Coal and Steel Community, then the European Economic Community (EEC) and finally the European Union (EU), developments that Monnet and Schuman could have only dreamed of. It became, in fact, a much greater success than they had intended. At least, until now. I listened to the dissenting voices, from people committed, in their own personal worlds, to widely different outcomes. Their visions are further apart than, say, the planet Mercury is from the distant Oort cloud.

The Conference project was launched on 19 April, 2021; coincidentally my birthday. It was opened to a fanfare and to high hopes of Europe’s member states moving forward together. “The platform represents a key tool to allow citizens to participate, and have a say on the Future of Europe,” said the President of the European Parliament, David Sassoli. “We must be certain that their voices will be heard and that they have a role in the decision-making, regardless of the COVID-19 pandemic.”

Certainly, the importance of listening to the public was stressed several times, even if those doing the stressing disagreed about what the public are saying. “Only a democratic Europe has a future,” the Conference heard from German Christian Democrat MEP Manfred Weber, the leader of the European People’s Party (EPP) group, “Brexit taught us that.” In other words, the EU’s leadership must listen more attentively to rumblings of discontent, wherever they may originate. Brexit came as a shock to a leadership that had grown complacent, and it came as a huge disappointment to Commissioner (and former MEP) Mairead McGuinness. “I chaired the last debate,” she told the conference, “Where the UK were no longer leaving and were on the way out, and I chaired with great sadness.

And Brexit brought back words: border, barriers; words that had disappeared because of EU membership. But it’s not physical barriers that I worry about most; it’s the barrier of minds and hearts.” It could be argued, perhaps, that those barriers of minds and hearts never really went away. They were merely hidden under the early enthusiasm for cooperation and joint development, under leaders who remembered World War II. Now, with the inauguration of the Conference on the Future of Europe, the EU’s various leading lights will hear the views of the citizens. I rather think they may be surprised by the level of narrow nationalism that it will uncover, but that doesn’t change the urge to listen to what the people are saying. “It’s about time that we start,” said Ana Paula Zacarius, Portugal’s Secretary of State for European Affairs, at the opening of the session, “It’s about time that we build our future together, our common future. And let’s make this exercise the best that we can.” Zacarius was one of three co-chairs of the session, the others being MP and former Belgian Prime Minister Guy Verhofstadt and EU Commission Vice-president Dubravka Šuica.

I cannot imagine anyone disagreeing with Zacarius’s sentiment, although there may be many ways of looking at it. It’s a bit like religion. 85% of the world’s population claim to be followers of one faith or another, the vast majority linked to one of the five major faiths: Christianity, Islam, Judaism, Buddhism or Hinduism. Get them all together, however, and there will be disagreements and disputes not so much between one faith and another (although that’s bound to happen, too) as between the followers of a single religion who can’t agree on the correct interpretation of one article of faith or another. The more people you gather under a single banner, it seems, the more rows spring up among the faithful as to who’s right. That’s certainly the case with Europe. For some, it should be nothing more than a trading group for the selling and buying of each other’s output. For others, it should be a union of like-minded peoples sharing common standards, values and laws. There is a vast gap between those two viewpoints. It’s what makes the mountain of obstacles lying in the path of this conference on the Future of Europe even higher. “This is a huge responsibility,” said Zacarius. “We have to make this work. We have to have concrete results at the end of it. Together, we’ll be stronger.” Can it be done? I’m reminded of Mao Zedong’s reply when he was asked some time in the 1950s if the French Revolution had worked. After a pause, he said: “It’s too early to say.”

YOU SAY YOU WANT A REVOLUTION (John Lennon, 1968)

For some Green campaigners and those fighting for social justice, the EU provides an opportunity to impose new rules and regulations about things like product safety, environmental protection and workers’ rights. There are others, however, openly campaigning for the exact opposite. The European Commission is working on a proposal to protect cross-border investments in the EU, due for publication in autumn 2021. There are fears, however, that it could include a swathe of new legal privileges for corporations. A number of the largest companies have banded together to lobby for generous financial compensation in cases where new legislation, brought in to protect the environment, consumer safety and workers’ rights costs large companies money. They want a legal entity, removed from the European Court of Justice, and which would decide how much a government should pay in damages for any business-unfriendly legislation that could harm the companies (or at least, the companies’ profits and thereby its shareholders’ dividends).

It all began in 2018 with an important ruling in the EU’s Court of Justice (CJEU), when around 130 ‘bilateral investment treaties (BITs)’ between member states were set aside and ruled illegal. These treaties had allowed investors to by-pass national courts whenever decisions taken at government level hampered their investments in some way, suing member states in front of tribunals ruled over by private lawyers. The CJEU ruled that such settlements had been illegal as they had ignored the EU’s own courts. The businesses and the legal profession could see a risk to the profits that the previous system had brought in. Business groups started lobbying the European Commission for a new justice system to run alongside the CJEU that would allow member companies to sue a government that brought in new laws on, for instance, the rights of workers in the contract-free “gig economy”, or the use and disposal of plastics or other harmful materials. The large banks have been at the forefront of the lobbying campaign, even though the whole idea is based on the rather surprising notion that businesses are not sufficiently protected by existing EU law, applied through an existing EU court. If they succeed, it will discourage member state governments from bringing in new measures to protect, say, the environment, secure fair holiday pay and decent wages or to ensure that the “polluter pays” principle applies in all cases.

According to Corporate Europe Observatory, “Industry wants to change EU law so that it mirrors the substantive investor protections and wildly speculative damage calculation methods which are common in international investment law. Provisions such as fair and equitable treatment should be ‘codified, specified and further developed’ in new EU legislation, according to Comerzbank and Deutsches Akieninstitut. This would risk driving up costs for public interest regulations in the EU, making it easier for businesses to secure large amount of compensation paid out by the public purse”. So already we can see the enormous differences of views between those involved in businesses, banking and the legal profession and, say, those connected with Corporate Europe Observatory. The whole affair has prompted the Austrian Chamber of Labour to remark: “While the Commission has long ignored workers’ requests to create minimum social standards for the EU…complaints about the lack of protection for investors, on the other hand, have immediately prompted the Commission to run a consultation on the issue”.

Whoever wins the argument, there’s no shortage of people already put their names down to have their say on Europe’s future, or who have already had it, including 108 members of the European Parliament, two people from each member state of the European Council (making 54 in all), three members of the European Commission, 108 from all the national parliaments, on an equal footing, and various members of civil society. For instance, there were or will be (the process is far from finished) 80 people representing the European Citizens’ Panels, one third of them under 25 years old, as well as 27 from Citizens’ Panels or Conference events linked to the project The selection process is not yet complete. They will be joined by the President of the European Youth Forum. In addition, 18 representatives from both the Committee of the Regions and the European Economic and Social Committee, and another eight from both social partners and civil society will also take part. The High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy may take part in discussions about the EU’s international rôle and an attempt will be made to ensure that the Conference Plenary is gender balanced. It’s a lot of people, but they’re people already committed in one way or another to the European way of resolving issues. It’s doubtful if any of the people who voted for Brexit would have chosen to take part at all. It has always been easier to jeer and shout “boo!” than to frame a constructive idea.

This time, the EU and its various bodies have offered a multilingual access point for anybody – everybody – to weigh in with their proposals and suggestions. It’s an excellent idea but forgive me if I express my doubts: what tends to happen when the chair opens the floor is that special interest groups tend to hog the debating time and end up taking over the event. You know what I mean: just as the meeting of your local golf club, amateur dramatic society, reading group or whatever is drawing to a close, the chair bangs the gavel and says something like “Is there any other business just before I close this meeting?”. You can almost taste the drink awaiting you in the club bar, but the group’s principle bore then gets to his or her feet and intones those dreaded words (or something else very much like them). “If I might just draw the Chair’s attention to Paragraph 3, subsection 14C of last month’s minutes,” he/she says, “I think you’ll find that the emphasis on the third line of parts iiib to iiid has been overstated and requires rewriting in the way I originally proposed.” And with a sinking heart, you know you’re going to be there for hours, or at least until long after the bar closes. Inviting everyone to comment and to make proposals whilst excluding the determined bores of this world is never going to be easy.

JOINING AND QUITTING

In the years following the Second World War, there had been several attempts to create some kind of pan-European, multinational organisation, but always national interests had got in the way (they still do). The bodies that succeeding in emerging from this slough of despond have been useful over the years – the Organisation for European Economic Co-operation (OEEC) and, of course, the Council of Europe. Both are still going strong and serve useful (if rather different) purposes, but they fall short of the sort of bodies dreamed of by Jean Monnet. Convinced Europeans like him had learned a hard lesson: the idea of European integration meant different things to different people; the urge for something more solid and tightly bound came mainly from the United States, strangely, and it was mainly motivated by an urge to make the administration of the Marshall Plan easier. One hopeful body, the Western European Union (WEU), founded in 1948, was intended as a way towards wide-ranging European cooperation, but remained primarily military in nature.

Proposals for a political and parliamentary structure with real powers foundered on opposition from the United Kingdom, and the resulting Council of Europe was, in the words of Dirk Spierenburg, “little more than a caricature of the original idea”. Spierenburg was writing a history of the High Authority of the European Coal and Steel Community, the early precursor of what would eventually become the European Commission in his snappily-titled book, ‘The History of the High Authority of the European Coal and Steel Community: Supranationality in Operation’. I was fortunate enough to have a close connection with this book (which is a lot more interesting than its title suggests): when I first arrived in Brussels I was recruited by an obscure department of the European Commission to help Spierenburg. Originally co-written in French by both Spierenburg and the then Professor of History at the University of Strasbourg III, Raymond Poidevin, the two were not happy with the English translation and wanted it reviewed and, if necessary, rewritten in part, a job that fortuitously fell to me.

It meant having monthly meetings with Spierenburg in the disused cafeteria of an obscure Commission building just off Rue du Trône, where he told me a lot of anecdotes about those early days, as well as answering my questions concerning what certain segments of the book meant. They were quite long, meandering chats over cups of appalling Commission coffee (it’s much better these days) but they were thoroughly enjoyable. In places, the English used in the translation was so ugly and arcane that I had to re-translate from the original to understand what it meant. You must recall that there were no laptop computers in those days and desk computers (large and slow) were only available to the rich, so no spell-check, no Google, nor hidden resources. All I had were the manuscripts and my hand-written notes from my fascinating meetings with Spierenburg. That’s how I learned about the origins of what was still the European Economic Community (EEC) at the time. I was told how various ideas had been rejected by various governments, with the British being especially wary of any pan-European body with real powers. ‘Plus ça change,’ as the saying goes.

A few years later, I was to conduct a television interview with the late Cosmo Russell, an early British enthusiast for European unity who joined the staff of the Council of Europe in Strasbourg in 1949 and then worked in Brussels at the European Commission from 1972 to 1986. Multilingual, he lived a large part of his life in Continental Europe, although I interviewed him at his home in leafy suburbia in the UK long after he had retired. He told me how he had always enthused to his political masters about the advantages of European nations working together.

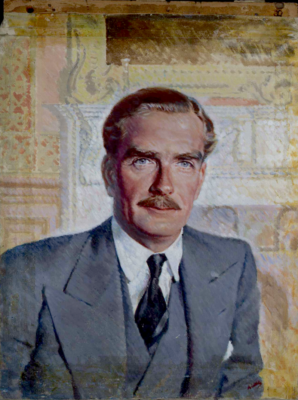

On one occasion, he said, he’d been called to report on some project or other to Sir Anthony Eden during his brief term as Prime Minister (1955-57) and found him sitting out on his terrace. As he approached, he told me, Eden pulled a face and said “You’re not going to bang on and on to me about Europe again, are you Cosmo?” Britain’s political classes (with few but notable exceptions: Sir Edward Heath and Tony Blair, for instance) have rarely favoured closer European union.

More recently, UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson has said of his country’s divorce from Europe “we have taken back control of every jot and tittle of our regulation” without feeling the need to explain what he means. It sounds like gobbledegook. After all, under a separate treaty, NATO has the power to order Britain to go to war, something the EU could never have done. Similarly, all trade deals involve agreements about retaining standards for imports and exports and other fine details. Hardly “every jot and tittle”, then; international relations simply don’t work like that.

It’s very clear from the Brexit referendum and from subsequent election results that Johnson has a majority of the British people – at least those living in England and parts of Wales – on his side. After all, the anti-European stories he used to make up for the Daily Telegraph were picked up and re-used by many other journals, apparently without bothering to fact-check them. Johnson said later that concocting these daft tales was “the greatest fun he’d had in journalism” (I never saw journalism as ‘fiction-writing’) and described it as being like throwing rocks over his neighbour’s wall and listening to the crash of greenhouse glass breaking. Heath was wrong about British attitudes to Europe at least early in the UK’s membership, when Harold Wilson’s government held a referendum in 1975 that returned a 67% to 33% in favour of membership. I remember talking once with Heath at the European Parliament in Strasbourg, just outside the meeting room of the centre-right European People’s Party, of which Britain’s Conservatives were, at that time, members. Among leading Conservatives who were critical of the EU was Sir John Redwood. “Opponents of Europe in your party are highly intelligent people,” commented one of the other journalists taking part in the conversation, “After all, Sir John Redwood is a fellow of All Souls college in Oxford.”

All Souls is a very exclusive establishment, devoted to research, according to its website, mainly in the humanities, and accepting no undergraduates. Heath frowned. “No, they’re not intelligent,” he snapped, “they’re just bigots.” Redwood’s hatred of Monet’s European dream seems to be almost visceral, even to this day. He remains a back-bench MP, still posting Euro-sceptic tweets, even after Britain has departed, which seems rather like complaining that you didn’t like the food after you’ve left the restaurant.

DESPERATE TIMES, DISPARATE COUNTRIES

Britain is not the only country to have difficulties with Europe at the moment. Think of France’s beleaguered president Emmanuel Macron. In the recent mid-term election, his La République en Marche effectively came fifth, with just some 11% of the vote. His far-right populist rival for the presidency, Marine Le Pen, and her party, Rassemblement National, did far worse than expected, too. She seems to have lost out largely to disinterest: the turn-out of just 35% was far lower than expected.

Le Pen’s party has lost favour with older voters and relies on what used to be called the “blue collar” vote, but after the election had twice been postponed, interest in the result was low, especially among young voters. Only an estimated 16% of those aged between 18 and 24 bothered to vote. The parties that came off best were the age-old mainstream rivals, such as the centre-right Les Républicains and the Socialists, but the real winner was apathy, which is worrying with a Presidential election less than a year away.

Germany is still headed by the Christian Democratic Union and its sister party, the Christian Social Union, their main rival being Germany’s oldest political party, the Social Democratic Party (SPD), founded in 1875, which sometimes enjoys the support of the Greens. In the next election for Chancellor, the likely winner will be someone most people outside Germany have never heard of: Armin Laschet, if the CDU/CSU win (which seems likely) or Olaf Scholz if the vote goes to the SDP. The shadow of Angela Merkel, however, is likely to hang over the future of whoever wins, such has been her influence over German politics. As the largest countries, France and Germany carry a lot of weight in Europe, but the EU, of course, has twenty-seven member countries, including two that sometimes cause concern in the other twenty-five. Poland has two main parties, the right-wing conservative Prawo i Sprawiedliwość (PiS), which means Law and Justice, and the moderate centrist Platforma Obywatelska (PO), which means Civic Platform. There are a large number of other smaller parties, too, the most significant of them being Nowa Lewica (SLD), or New Left (Poland).

In Hungary, the right-wing Fidesz–KDNP holds almost 50% of the seats in the unicameral National Assembly, followed by the equally right-wing Jobbik – Movement for a Better Hungary. The electoral process in Hungary seems not to matter much, with prime minister Viktor Orbán openly ignoring democratic institutions such as a free press and freedom of expression in pursuit of what he has called “illiberal democracy”. As The Atlantic reported in April 2021, “With this week’s passage of a law effectively removing any oversight and silencing any criticism of the Hungarian government, Prime Minister Viktor Orbán can now rule by decree for an indefinite period of time.”

Maybe that’s what the Hungarian electorate wants. The EU seems powerless to compel Poland to lift its ban on LGBTI+ people living as they want, and nor can it have any impact on Orbán while his country is the only member state of the EU to have been designated only “partly free” by Freedom House, a think tank. I can’t imagine Orbán has lost any sleep over that. The remaining twenty-five members may occasionally squabble, but most issues can generally be resolved with patience. The problems posed for the EU by Poland and Hungary are less tractable, as are problems posed by Russia and Turkey for the Council of Europe. Poland and Hungary are often difficult for the Council of Europe, too, and for much the same reason. Finding a way to ensure compliance with the rules from countries that are openly disregarding them, is as yet un unresolved issue.

“We are facing challenges. Everybody knows this,” said Ana Paula Zacarius, “and we need to use this opportunity to engage with citizens and with other stake-holders of the EU to see how we can emerge stronger from this Covid-19 crisis.” Indeed, it’s not just a case of overcoming a terrible and extremely infectious viral disease and all the economic damage it has caused; the inevitable and essential restrictions on travel, on movement and on meeting up together has been a gift to autocratic governments which have long looked for a good excuse to impose such things. One of the EU’s major problems is that very few people living in Europe understand how the EU works or what it does, which helps explain its relative lack of popularity. Conducting street interviews (known as ‘vox pops’) in the UK before it finally left the EU, I was surprised and disturbed at the number of people who didn’t like the EU because they believed it meant Britain was always taking orders from Germany. That is mainly (but not exclusively) the fault of the UK’s often anti-European media, whose attachment to truth can be somewhat tenuous on European issues.

SHAPING A FUTURE, ANY FUTURE

This problem was highlighted at the Future of Europe plenary by the President of the Committee of the Regions, Apostolos Tzitzikostas, who told the conference that the lack of knowledge is not the fault of the average European.

They are unaware that it’s because of the EU that we “breathe cleaner air, consume higher quality products, that we have better-equipped hospitals and digitised schools and public services”. So what is the cause of this lack of knowledge? “It means that we have done something wrong,” Tzitzikostas said. “And this is what we need to do during this conference. We need to listen. We need a credible dialogue. And we need to focus on the real needs and the issues which matter to the citizens. And above all, we need to create a new vision that will unite us.” The problem seems to be that not only are people largely unaware of what Europe has done for them, but they don’t want to be told. When things go well, the national government (or the local authority) likes to take the credit. When things go wrong, these same bodies pass the blame on to Brussels. As the late Northern Irish MEP John Hume used to say: “Success has many fathers; failure in an orphan”. It’s not original; he was quoting Count Galezzo Ciano (Mussolini’s son-in-law) and possibly also the Roman general, Gnaeus Julius Agricola. But whoever said it first, it clearly applies in the EU’s case.

Engaging the young is, perhaps, the most important thing to do, but nobody really seems to know how. In a report for the Council of Europe Parliamentary Assembly (PACE), Finnish MP Inka Hopsu argues that more countries should act upon UN Security Resolution 2250 by getting young people more involved in conflict prevention and resolution. This will not be easy; it seems too many young people are put off a political career by the slow pace of preferment. As she points out in her report, adopted in June 2021, only 3.9% of national parliamentarians in Europe are under 30 years old. By the time they’ve climbed the greasy pole, they are no longer young, either. It’s a difficult thing to overcome but, says Hopsu, it’s not insurmountable, if political party officials act. “I think the political parties carry a lot of the responsibility here,” she told me, “So, during election campaigns, the young people should be involved in the electoral lists and taken on as candidates. And also during the campaigns, they should pay respect to them, and lift them up, really, and even some countries might need a quota for young people, in the parliament, in the municipality.” It’s a good idea, but successful older politicians have often had to be persuaded to help those younger than themselves who could turn out to be future rivals. As the old saying goes, turkeys don’t vote for Christmas. However, the Conference on the Future of Europe is still inviting citizens and organisations to participate and table new ideas. Why not give it a try? Perhaps some young person, as yet unknown, may yet come forward with a revolutionary and brilliant solution to Europe’s problems. If so, let’s hope someone is listening.