NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg and French President Emmanuel Macron © Nato

Some commentators are likening France’s current president, Emmanuel Macron, to one of his predecessors, Charles de Gaulle, largely because some of his comments have cast vague doubt on his commitment to NATO. De Gaulle had been elected in 1958 at the height of the Cold War, but it became clear that the United States was unlikely to weigh into a real European war in defence of its NATO allies using nuclear weapons. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger had stated openly that no US president would ever risk the safety of the housewife in Kansas to protect the housewife in Hamburg. Or, of course, Lyon, Limoges or Lille. Furthermore, European nations believed in dialogue with the Communist states while the Americans wanted nothing to do with them.

De Gaulle concluded that if America wouldn’t come to Europe’s aid in a crisis there was not much point in staying fully engaged in NATO. This view had been hardened by the US decision to pull the plug on France and the UK over their seizure of the Suez Canal from Gamal Abdel Nasser, who had nationalised it for Egypt. Washington feared it would drive the Arab nations that they were courting into the arms of the Soviets. They were also annoyed at the lack of European support in Vietnam, whereas several European nations had helped them during the Korean War.

In 1959, de Gaulle, speaking at France’s École Militaire, announced his determination that France would have its own force de frappe: a nuclear weapon not dependent upon the US. Robert McNamara, US Secretary of Defence from 1961 to 68, wanted all the west’s nuclear weapons under American control and described the idea that France would have its own as “dangerous, expensive, prone to obsolescence and lacking in credibility.” McNamara also increased America’s involvement in Vietnam, so his political record is hardly blemish-free in the eyes of many. As explained in a lecture by Dr. Jamie Shea, former NATO’s Deputy Assistant Secretary General for Emerging Security Challenges, “In 1966, at a very famous press conference, de Gaulle announced that he was pulling out of NATO’s military structure and ordered SHAPE (Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe) out of France.” He did not order the civilian offices of NATO out of France but they chose to go anyway, out of solidarity with their colleagues, to the severe disappointment of many of the staff, who had liked being based in France. They moved to Brussels instead. It may not have been the big deal it seemed at the time. As Shea said, “First of all, the French were very careful to stay in NATO military programmes where they saw an advantage. The NADGE air defence system, they kept the nuclear tasks in Germany. They kept a lot of personnel in NATO.”

In fact, France withdrew from the Integrated Military Command structure, but it never left NATO altogether. Under Nicolas Sarkozy, after 43 years, France returned fully to the fold. Some US observers, though, are now saying that Macron wants to restore France’s ‘military sovereignty’, ending a reliance of any kind on Washington.

In an on-line version of The Atlantic, columnist Kori Schake, Director of Foreign and Defense Policy at the American Enterprise Institute, described Macron as “a throwback to his predecessor Charles de Gaulle, who resuscitated France’s self-esteem after the grief of occupation in World War II. Like de Gaulle, Macron would unify Europe under France’s conception, with Germany footing the bill.” Perhaps, unlike the apparently rather Francophobe Ms. Schake, Macron simply doesn’t trust Washington. France under Macron, however, remains a player on the world’s military stage.

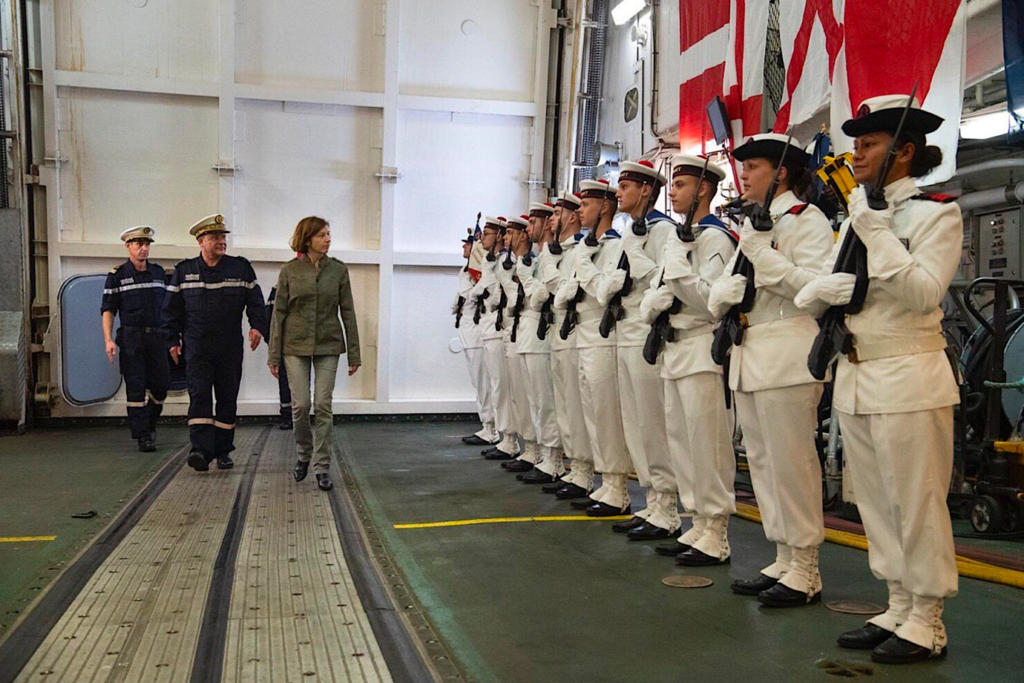

It is France that is almost single-handedly fighting the jihadists in the Sahel region. French forces, headquartered at N’Djamena, the capital of Chad, have a base in Gao, central Mali, where jihadist forces slaughtered almost 5,000 people in 2019. France’s Defence Minister, Florence Parly, has visited the base and been briefed by the soldiers doing the fighting. The enemy there is a group calling itself Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS) and it was soldiers from France, Niger and Mali, helped by French Special Forces and using intelligence supplied by the US, who tracked the jihadists.

They killed a large number of them and seized weapons, motorcycles, fuel and food supplies in what one French officer described as an “intense” encounter. France has more than 5,000 troops engaged in what is called Operation Barkhane. No other European country has as many forces on the ground there. The United Nations has a parallel peacekeeping operation in the area, but European forces contributing to it are numbered in the low hundreds. France doesn’t want to be seen as neo-colonialist and Macron has hosted the leaders of the five affected countries – Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania and Niger – to a conference, seeking and getting their support for a continuing French presence.

Some other European forces have assisted in French-led operations, but the main burden is born by France. It’s a long-term commitment, made more difficult by the relative political instability in the area, but persuading France’s allies that it’s a war worth winning has been hard. French forces have also been heavily involved in the Middle East and in the Balkans. No-one can accuse Macron of shirking France’s global military responsibilities.

MISREADING THE SCIENCE

No-one is quite sure who first said “après moi, le déluge”, but it seems to have been either King Louis XV or his chief mistress, Madame de Pompadour. It was most probably said as “après nous, le déluge”, and the most commonly held belief is that it meant “after us comes chaos” (that’s how my Harrap Shorter French Dictionary explains it), but it could also have been a prediction of the coming French Revolution or even of genuine floods, the literal meaning of the expression. If the first option is correct, and as it was supposedly first said in 1757, whoever said it had amazing foresight; the Revolution didn’t start until 32 years later, although the obscene gap between the uber-rich and the starving poor must have made it virtually inevitable. It could also have meant “who cares what happens after we’ve gone?”, said in response to references being made to increasing unhappiness about the lavish royal lifestyle at a time when most French citizens were on (or below) the breadline.

The France of Emmanuel Macron is very different from Louis XV’s kingdom, and the unrest of today has rather different, arguably more complex causes. They are there, though. Charles Dickens refers to the extreme poverty of France under the Ancien Régime in ‘A Tale of Two Cities’. Early in the book, after a wine cask is broken in the Sainte Antoine area of Paris and the poor nearby have scooped up and drunk the pools of muddy wine among the cobbles in their filthy hands, Dickens mentions “the woman who had left on a doorstep the little pot of hot ashes, at which she had been trying to soften the pain in her own starved fingers and toes, or in those of her child”. He mentions poverty in London, too, but clearly believed that things were considerably worse in Paris.

France was in a bad way following its losses in the Seven Years War (for which Madame de Pompadour, a leading Royal advisor as well as Louis’ bed mate, was partially blamed) and its poorly led and badly indebted government. But members of the nobility were still living the high life and telling themselves that it was the will of God that made them rich while so many others were starving. Certainly, it was the profligacy of the ultra-rich and the starvation of the masses that fuelled the Revolution in 1789, but that may not have been what Louis and his mistress meant.

Halley’s Comet was predicted to reappear in late 1758 or early 1759 (it appeared in 1758) and with it being a popular topic for debate at the time, some “experts” predicted that it would cause flooding similar to that faced by the biblical Noah, in which case “après nous, le déluge” made literal sense. Sir Isaac Newton, a brilliant physicist who none-the-less took the Bible literally, had supported a theory that it was water from this comet’s tail that had caused the biblical flood. Anyway, Louis XV survived the floods that never came and died of smallpox in 1774, thus missing the revolution that saw his son, Louis XVI, named Citizen Louis Capet at his trial, go to the guillotine.

Macron’s problems will not lead to revolution, even if his popularity rating by late November 2020 had fallen to just 21%, according to a YouGov poll. When you consider that back in July it reached an impressive 50%, that’s quite a fall. It sounds pretty drastic but those who actively disapprove of him make up only 27% while 34% say they’re neutral. That leaves 18% who seem to have no opinion at all, and opinion polls have fairly consistently got it wrong anyway (whatever happened to Joe Biden’s anticipated landslide?). In any case, Macron has no need to listen out for the sound of the tumbrils rumbling towards the Elysée Palace just yet.

The YouGov poll also asked which politician people would choose to be “world king” and a surprising 9% chose Boris Johnson, Britain’s vain and struggling prime minister, which would put him 1% ahead of Angela Merkel. There’s an old saying in the north of England, popular in Yorkshire and Lancashire: “there’s nowt so queer as folk” (there is nothing so strange as people), which means that many of us can be very unpredictable in our tastes. Macron only got 1%, but he shouldn’t worry unduly; 50% said they wouldn’t choose any of those listed in the poll and 12% didn’t know. Less surprisingly, perhaps, Xi Jinping and Kim Jong Un got no takers at all.

Macron should be more worried by the fact that his popularity, which goes up and down like the water in a pool with a wave machine, is still slipping. He is seen more and more as the President for big business and the rich. His immediate post-election popularity, now dwindling in history’s rear view mirror, has been damaged. Back in the early summer, one French newspaper was suggesting that Macron was considering triggering a new election by resigning in the hope that his successful handling of the coronavirus epidemic would ensure his re-election. The Elysée Palace denied it at the time and it certainly seems extremely unlikely. Even then, his popularity rating was only 38% and his then prime minister, Edouard Philippe, was not only more popular but talking about entering politics on his own account, becoming a potential rival.

He resigned during a re-shuffle in July. As a centre-right politician, he posed a threat to Macron’s La République En Marche party, although he has since come under investigation by the Law Court of the Republic, which looks into allegations of ministerial misconduct, for his handling of the COVID-19 pandemic, so his chances of winning the presidency have almost certainly shrunk. His replacement, Jean Castex, was a virtual unknown, charged with getting France out of lockdown, which has earned him the nickname “Monsieur Déconfinement”.

LA RÉPUBLIQUE EN MARCHE, ARRIÈRE?

Macron, with his newly formed political party was elected in 2017 on a pro-European, pro-business agenda, promising reforms that would include making France’s labour market less sclerotic. However, it meant taking on France’s powerful trades unions, which had enjoyed considerable influence ever since the Second World War. Macron’s reforms to taxation led to higher fuel prices which, many felt, fell disproportionately upon the working and lower-middle classes, especially away from the big cities. An on-line petition in May 2018 protesting about it attracted almost a million signatures. Six months later, the Gilets Jaunes – the Yellow Jackets (a garment referred to as ‘hi-vis’ jackets in the UK because they are reflective and are the near-universal outer garment of outdoor workers) – took to the streets in what became an increasingly visible and later violent protest. They wanted the fuel taxes reduced and the reintroduction of the wealth tax, imposed by a Socialist government in 1981 as the Impȏt de solidarité sur la fortune, or ISF, then removed, then reimposed before finally being morphed into the Impȏt sur la fortune immobilière (IFI) by Macron’s government. The original ISF applied to all kinds of wealth, moveable, immoveable or financial, in excess of €1.3-million. The IFI applies only to real estate, so other types of asset are exempt. Not surprisingly, the very wealthy prefer the IFI to the ISF.

On his blog in October 2017, the French economist Thomas Piketty wrote: “let us say it straight away: the abolition of the wealth tax (ISF) constitutes a serious moral, economic and historical fault. This decision shows a deep misunderstanding of the unequal challenges posed by globalization.” Piketty, who came to global fame with the surprising runaway success of his economics book ‘Capital’, wrote: “If we add the gifts granted to dividends and interest (which will henceforth be taxed at a maximum rate of 30%, against 55% for salaries and non-salaried activity income), we end up with a total cost exceeding 5 billion Euros. This is the equivalent of 40% of the total budget allocated to universities and higher education, which will stagnate at 13.4 billion in 2018, while the number of students continues to increase, and the priority should be to invest in training. We bet that students will remember when the government tries to add selection to austerity in the coming months.” This was written, of course, before the SARS-CoV-2 virus came along. Piketty is a firm believer in a wealth tax and so, it seems, were the Gilets Jaunes.

Macron, a former investment banker, is supposedly a centrist, owing nothing to the parties of the left and right that have traditionally run France, but he is increasingly seen as a figure of the right. For many of those who gave him over 66% of the vote, he was a breath of fresh air after François Hollande, whom I always found a charming and somewhat self-deprecating man in real life, although the French public viewed him as a bit stuffy. A French friend told me that Macron had cast himself as France’s answer to Margaret Thatcher, which would put him very much on the political right, albeit less inclined to hit opponents with a handbag. When his private bodyguard was seen to assault May Day protestors, he was slow to react and criticise and this did nothing for his public image as a ‘man of the people’. In September he allegedly told an unemployed man that he could easily get a job if he tried. This did not go down well, either. Nor has his lack of success with the French economy, which has not seen the hoped-for increase in growth or fall in unemployment.

More recently, Macron has attracted condemnation and even death threats from Islamic countries that think he was wrong in his reaction to the brutal murder of Samuel Paty. Paty was a history teacher who had shown his class some of the cartoons of Muhammed from the satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo during a class about freedom of speech.

Paty had warned his students in advance and given them the option of not looking, or even leaving the room, but an enraged Tweet by a supposed parent (not actually a parent of anyone in the class) who claimed to have been there (but wasn’t) was enough to inspire a young extremist to behead him. Macron’s resulting attack on Islamist extremism – of which France has seen more than its fair share – earned him rebukes from the leaders of some Muslim countries and demonstrations by Muslim groups. Even some western newspapers in countries that share France’s views on freedom of speech and intolerance have criticised Macron for what was seen by some as intemperate language in his response. Macron was so incensed about the hostile reports that he got his office to arrange for him to give an interview to the New York Times. In it, he spoke of his disappointment that what France calls the Anglo-American press appeared to be ambivalent in its support for the Republic. “When I see, in that context, several newspapers which I believe are from countries that share our values — journalists who write in a country that is the heir to the Enlightenment and the French Revolution — when I see them legitimizing this violence and saying that the heart of the problem is that France is racist and Islamophobic, then I say the founding principles have been lost.” The New York Times columnist Ben Smith set Macron’s complaint in context. “More than 250 people have died in terror attacks in France since 2015, the most in any Western country. Mr. Macron, a centrist modernizer who has been a bulwark against Europe’s Trumpian right-wing populism, said the English-language — and particularly, American — media were imposing their own values on a different society.”

MADDENED, MALIGNED, MISQUOTED

Macron has expressed outrage before about being misunderstood and even misreported. A complaint to Britain’s Financial Times even led to one of its articles being taken down from the Internet, said to be a first for the august and respected journal. In the offending article, the writer had said “Macron’s war on Islamic separatism only divides France further,” when he had used the expression “Islamist separatism”, which has a distinctly different meaning. ‘Islamic’ and ‘Islamist’ are very different words. In clamping down on Islamic groups, including Muslim charities, Macron was accused of targeting ordinary Muslims, not terrorists. In France, perhaps more than in any other European country, a person’s choice of religion is up to them – as long as they continue to respect those of other faiths or none. “Our model is universalist, not multiculturalist,” Macron told the New York Times. “In our society, I don’t care whether someone is Black, yellow or white, whether they are Catholic or Muslim, a person is first and foremost a citizen.” Liberté, égalité, fraternité, indeed. Other western countries, though, and sections of their media have put some of the blame for Islamist attacks on Macron and on France’s very determined secularism. Macron insists that it really is secularism, not racism or Islamophobia, although the Washington Post suggested that the French government seems more concerned to influence the way in which Islam is practised than at looking into why French Muslims feel alienated. Most Muslims, after all, are happy to follow their religion and abide by its precepts in completely lawful and peaceful ways, wherever they live and without seeking to overthrow the state.

Certainly, the French government’s countermeasures after the murder of Paty and the attacks that followed have been more large-scale than after previous attacks. There were some 120 house searches, associations accused of spreading Islamist rhetoric were closed down and bodies suspected of raising funds for Islamist causes were investigated, while pressure was put on social media companies to ensure their sites do not permit incitement to violence. Given how many previous attacks there had been in France, Macron’s determination to stop it may be understandable, although many political analysts suspect that it owes a lot to his concerns over the next presidential election, scheduled for 2022.

A recent poll to discover who the French people would most trust to deal with terrorism was topped by the leader of the far-right National Rally (formerly the Front National), Marine Le Pen, who sees any public expression of Islam, however peaceful, as a threat to the state. Le Pen has been capitalising on Islamist terrorist attacks to bolster her position in a bid to win the Elysée Palace. National Rally is different from the Front National in that it is no longer officially antisemitic, but it remains strongly Eurosceptic, although Le Pen claims only to be ‘nationalist’. She was quick to blame the coordinated 2015 terrorist attack that left 130 dead and around 350 wounded on the liberal immigration policies of the then Socialist president, François Hollande. Macron is determined not to lose out in a similar way.

A VEILED THREAT?

His party is certainly not liberal politically. Although Macron has tried to avoid getting dragged into discussion on ‘burkinis’ and halal school meals, members of his party would clearly prefer them not to exist. A couple of months ago one of Macron’s MPs, Anne-Christine Lang, joined other more obviously right-wing legislators in walking out of the Assemblée National so she could avoid hearing testimony from a Muslim woman wearing a headscarf. They were supposed to be debating the effects of COVID-19 on young people with members of the students’ union, whose representative, Maryam Pougetoux, was a Muslim.

Lang claimed that, as a feminist, she could not accept the presence of someone dressed in that way. That inflexible view was criticised by Sandrine Morch, another En Marche MP who was chairing the session. She pointed out that there was no rule to prevent people attending a session wearing religious clothing, saying she would not allow a “fake discussion” around a headscarf to shift the focus of the meeting, when the future of the country’s young people was under discussion.

It goes without saying that France’s response to the Paty murder has drawn criticism from Islamic countries, with Turkey’s president, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, even questioning Macron’s sanity and imposing a ban on French products. France withdrew its ambassador in response. Macron has introduced a number of new measures, including putting pressure on the French Council of the Muslim Faith (CFCM) to establish a National Council of Imams from which serving Imams can obtain accreditation that can be removed if they step out of line. Additionally, Macron has introduced rules about home schooling, with harsher punishments for anyone trying to intimidate public officials on religious grounds. All children are to get a national identification number to be used to ensure their attendance at school, with punishments ranging from huge fines to six months in prison for parents who break the law. People will also be barred from sharing anyone’s personal information in such a way that it allows those wishing them harm to track them down. Civil liberties advocates are more concerned, however, about a ban on the public filming of the police, which has been seen as a bulwark against brutality. That response prompted angry protests all over France, with marchers bearing placards with such slogans as “La République En Marche Arrière”.

ARMED INDEPENDENCE

France is now the only country in the European Union to have a nuclear weapon, since the UK walked away. Both countries are, of course, still in NATO, in which Article 5 of the Washington Treaty remains of prime importance. Under it, an armed attack on any member is counted as an attack on all, obliging each member to take “such action as it deems necessary, including the use of armed force, to secure and maintain the security of the North Atlantic area.” It’s a strange thing that Britain voted to leave the EU, where it had the power to veto decisions, but not to leave NATO, which can order a country to go to war. Voters were not made aware of this. In his satirical song ‘Who’s Next’, the humourist and Harvard-educated mathematics lecturer Tom Lehrer – now aged 92 and retired – listed the countries that have a nuclear weapon. In one verse he suggested some tension in relations between France and the USA when he sang:

“Now France has got the bomb, but don’t you grieve,

Coz they’re on our side…I believe.”

The last two words were sung after a pause and a slight giggle, suggesting that Lehrer wanted to convey the idea that he wasn’t too sure about it. The song was first broadcast not long after de Gaulle’s decision to leave NATO’s Integrated Military Command structure. Macron has said in an interview that “What we are currently experiencing is the brain death of NATO,” by which he was referring to what he saw as a Trump-led US abandoning Europe. It’s hardly something new, given the comments made years ago by Robert McNamara and Henry Kissinger. But those comments were political and designed for a domestic audience. We must assume that Macron’s comments were, too. France’s Permanent Representative to NATO today, Ambassador Hélène Duchêne, has no intention of ignoring the Article 5 obligation to come to the aid of allies.

“NATO takes the necessary deterrence and defence measures against any threat and aggression and against any emerging security challenge which could compromise the fundamental security of one or several allies,” she wrote on France’s European and Foreign Affairs Ministry website. Article 5 has only been invoked once, in response to the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Centre on 11 September 2001, when fellow NATO members responded with a big anti-terrorism operation in the Mediterranean. There were conditions placed by France upon re-joining the Integrated Military Command Structures: France retains full discretion over its contribution to NATO operations, it keeps its nuclear independence, no French force can be placed under permanent NATO command in peacetime and it does not have to contribute to funding expenditures linked to decisions taken before it re-joined.

Macron has no intention of letting France get left behind in the new arms race. In early December he announced a new aircraft carrier that will be, like its predecessor, nuclear powered. Don’t expect to spot it at sea off the French coast any time soon: it will take until 2038 to become fully operational – just in time to replace the similarly nuclear-powered Charles de Gaulle, which entered into service in 2001. The new vessel will be France’s biggest-ever warship at around 75,000 tonnes and 300 metres in length, capable of speeds of around 27 knots.

That makes it smaller than America’s Gerald R. Ford and Nimitz class carriers but bigger than anything the United Kingdom, Russia or China can boast. Of course, as we all know, size isn’t everything, even if it confers bragging rights. It will also be carrying the latest aircraft, now in development but, according to France’s Armed Forces Minister, Florence Parly, it will be “bigger than the Rafale” and there will be 30 of them, making it a formidable vessel indeed. For the technically minded, the ship will be powered by two K22 generators, each giving out 220 megawatts. The Charles de Gaulle’s generators are smaller. This will be a very French undertaking, apart from the launch catapults, a field in which France lacks experience. They will be of the latest type – electromagnetic instead of steam-powered – and they will be imported from the US. The design phase will last until 2025 at a cost of around €900-million. The work will be carried out by Naval Group, which will, as usual, work with its main industrial partners, Chantiers de l’Atlantique, TechnicAtome and Dassault Aviation. Relatively few nations can boast nuclear-powered naval vessels and Macron is determined to keep France up there with the leaders.

France’s threats these days do not come so much from overseas, despite Macron’s spat with Turkey. The murderer of Paty was a French-born Muslim, radicalised by extremists and shot dead by police. France remains a major military player internationally, however, with more than 10,000 troops deployed not only in the Sahel but also in Iraq, Lebanon and the Central African Republic, among other places. The French forces have been accused of overstepping their brief to get involved in domestic politics, such the series of airstrikes in early 2019 which France launched to destroy a column of trucks.

The trucks were carrying soldiers trying to overthrow Chad’s president, Idriss Déby, so it was a matter of internal rebellion against an autocratic and unpopular leader. Déby rules a country rich in oil, uranium and gold but its people are dirt poor. According to the UN, 8% of new-born infants don’t live to see their first birthdays while 20% don’t make it to the age of 5. Déby lives richly enough though and spends much of the country’s income on his personal security, even though he knows he can rely on French protection. In an on-line article for The Conversation by Nathaniel K. Powell, a Research Associate at the Department of War Studies at King’s College, London, he claims that France’s main objective, going back to the 1960s, has been to prop up governments in Africa, even those led by blood-thirsty despots. Stability is the priority. Macron may be tough on insurgents in faraway places, but in common with other leaders in the secular west has yet to find an answer to Islamist radicalism that leads to terrorism and murder at home. It is the kind of problem that cannot be addressed with nuclear weapons, nor any other kind, nor by sending in his paratroopers. What’s the point in attacking bodies when the danger and hostility lurks out of sight, in the mind? Which way will a post-Macron France lean? Perhaps it will be a case of ‘Aprés moi, le déluge.’ At least that’s preferable to ‘Aprés moi, la déchéance’.