© Edm

We already use two types of money in the Euro area: central bank money, which basically means the banknotes and coins we carry around, and what’s known as “private money”, which is any money you may have borrowed from your bank, but it’s also the money shown as being yours on your bank statement and the payments you make using your credit or debit cards, because it’s money created by your bank. Yes, I know it’s all yours and only a banker or an economist would be interested in the finer points of detail. It’s your money and you spend it, without generally considering whether it’s central bank money or private. If you suffer the unfortunate fate of being mugged in the street, your attackers are not going to differentiate anyway. It was yours; now it’s theirs (unless the police get it back for you).

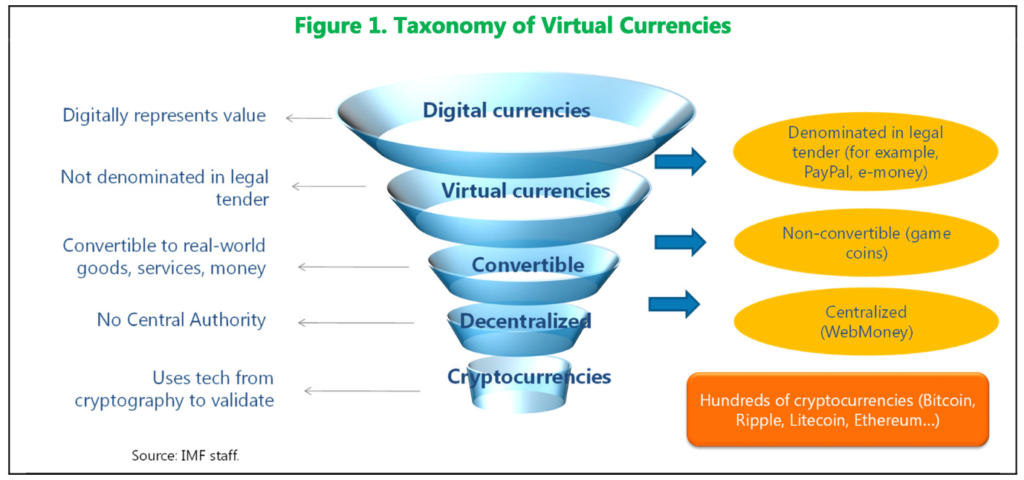

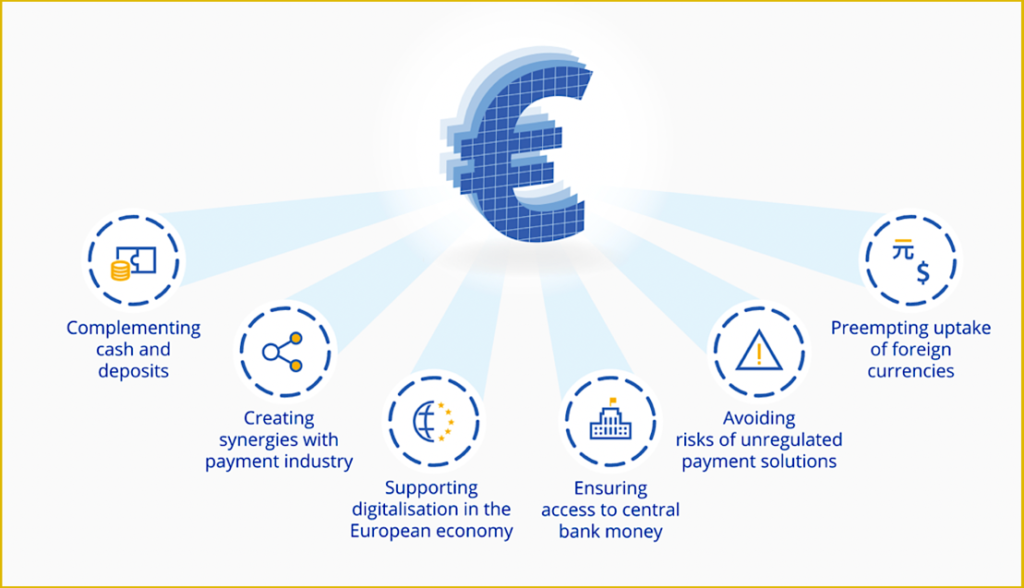

The European Central Bank (ECB) says it is creating digital euros as (and I quote) “an anchor of stability for our money in the digital age”. It would, says the ECB, “complement banknotes and coins, giving people an additional choice about how to pay”. That’s assuming we need one, of course. The Bank says a digital euro would offer an electronic means of payment that anyone could use “in the euro area.” The idea springs from a perceived demand for new “safe and trusted electronic payments” systems. How does it differ from other payment methods available to us? Well, there are no notes or coins, for a start. The ECB says that this allows for almost instantaneous transactions. However, as digital currencies are not issued by a governmental organisation, they are not actually legal tender, either, although they enable ownership to be transferred across what governments regard as their borders. Confusing, isn’t it? The ECB, in its 2015 publication, “Virtual currency schemes – a further analysis”, points out that a virtual currency can, in certain circumstances, be used as an alternative to money, in order to pay for specific goods or services over the Internet.

According to the ECB, digital money has no physical equivalence in the real world, although it acts like it in as much as you can receive, transfer, or exchange digital currency for the more traditional kind. It has no geographical or political borders. In its 2015 report, the ECB makes clear the fact it does not regard “virtual currencies” (such as crypto-currencies) as being at all the same thing, even though it uses the terms almost as though they are interchangeable. The ECB argues that virtual currency is not money or currency from a legal perspective, choosing to define it rather as a digital representation of value that has not been issued by a bank, a credit institution, or an e-money institution. In order for a digital currency to work, it needs a “virtual currency scheme” (VCS), a type of transactional body that has been developing for the last few years. The ECB has been looking closely at how they work and at how it might be possible to improve them.

According to the ECB, the VCS system mainly consists of new categories of actors, not previously involved in financial transactions. The Bank also mentions that new business models are starting to emerge, based upon obtaining, storing, accessing and transferring units of virtual currency, although the ECB admits that the purpose of some of them at present remains unclear. It is a very new field and payments using VCS are not widely accepted, as yet. VCS have their drawbacks for users, too: there is a distinct lack of transparency, as well as clarity and continuity, none of which helps instil certainty. People and companies prefer transparency and clarity when parting with large sums of money.

It would appear that some of the VCS that have been created have no obvious purpose at all, which leaves potential users uncertain and lacking in confidence.

| MORE TULIPS, ANYONE?

People are naturally even less trusting following the collapse of the crypto-currency boom, even though “central bank digital currencies” and crypto currencies are not the same. The big collapse happened with the sudden, unpredicted disappearance of FTX, the crypto-currency exchange which was, with a theoretical value of $32-billion, the third largest in the world. Up to that point, its owner and mastermind, Sam Bankman-Fried, was thought to be on his way to becoming the world’s first-ever trillionaire, with personal wealth estimated at $16-billion already. It’s all gone, leaving him being pursued by a million or so creditors. It turned out that FTX had lent some $8-billion of its assets to another of Bankman-Fried’s companies, despite such activity being expressly forbidden by FTX’s own terms of service. Not surprisingly, it left an $8-billion hole in the balance sheet, and investors don’t like that. Additionally, and very worryingly for investors, as soon as FTX declared its bankruptcy, millions of dollars started to flow mysteriously out of its accounts. It began to look less like a financial failure and more like a criminal conspiracy, although it may not be, of course. Reporting on FTX’s woes, The Economist magazine put the issue neatly into historical context: “Big personalities, incestuous loads, overnight collapses – these are the stuff of classic financial manias, from tulip fever in 17th century Holland to the South Sea Bubble in 18th century Britain to America’s banking crises in the early 1900s.”

History has a habit of repeating itself, especially where greed is concerned. Obviously, the ECB will be running its new digital currency with the sort of care and caution that such an ambitious operation demands. It can’t afford to let things go wrong. But making a fast buck was never the intention when the idea of digital euros was first floated.

The ECB points out that technological advances have triggered a rapid growth in virtual communities. Some of these communities have even created and circulated their own currencies (or at least tokens of exchange), providing a unit of account that’s all their own. As the ECB points out, we must bear in mind that these currencies (since that is how we must regard them) resemble money and also come with their own dedicated retail payment systems. They are really what a VCS is. The ECB defines three types of VCS: one is closed, such as the type used in an on-line game. The second type has a financial flow in only one direction with an established conversion rate for buying virtual currency with which to buy virtual goods or services (and sometimes real goods and services). The third type is more akin to real money, allowing a flow in either or both directions and effectively available to use to buy goods and services. A VCS may be set up to lock a customer or potential customer into a system through which they can obtain goods or services from one source only. Transactions using a VCS are recorded on what’s known as a blockchain, a vital facility that provides a secure decentralised record of such transactions.

It seems clear that virtual currencies are the future. A recent survey among sixty-six central banks conducted on behalf of the Bank for International Settlements revealed that more than 80% of them are working on developing their own digital currencies. But these are a bit special, because they are (or will be) central bank digital currencies (CBDCs), run by a central bank. The European Central Bank is one of them. The ECB denies that this is an attempt to keep up with fashionable trends, so why is it doing this? The Bank says it’s because it “has to be ready”. Ready for what? “Ready to embrace financial technological innovation which has the potential to transform payments and money faster, and in more disruptive ways, than ever before.” This statement formed part of a speech given at a virtual conference in 2020 by Yves Mersch, Vice-Chair of the ECB’s Supervisory Board. In his speech, Mersch foresaw a change in people’s behaviour concerning payments and spoke of the need to retain a direct link to the owner of the currency in question by maintaining their access to central bank liabilities in euros. He stated that cash gets a bad press – a fact that you, like me, probably find hard to credit – but also pointed out that demand for it remains high.

| CASH IN HAND (OR NOT?)

Mersch put it to his virtual audience that the bank should be looking ahead to a future in which central banks will be expected to provide the public with some form of digital currency. He said that electronic payments are already taking the place of cash in some countries whose own currencies are less appealing than the euro. Within the euro area itself, around 76% of transactions are carried out in cash. In fact, the demand for cash in the euro area, Mersch said, “currently outstrips the rate of nominal GDP growth.” Furthermore, he warned that: “In crisis times, the demand for cash surges even higher.” In fact, around mid-March 2022, the weekly increase in the value of banknotes in circulation almost reached the historical peak of €19-billion.

The ECB, it seems, is still not certain about the need for CBDCs; the current research is primarily analytical, and the outcome will depend on the preferences of households. Mersch assured his audience that the ECB is always keen to respond to the wishes of the euro’s users. He said that if the public suddenly expressed a desire for plastic or polymer banknotes in place of paper ones, the ECB “would happily accommodate them”. Although it remains uncertain if the ECB will opt for a digital currency, an appropriate design is already being drawn up so that the bank could do what is required quickly. A task force has been created to prepare the way.

Forbes Advisor website claims that a lot of countries are exploring the possibilities that CBDCs might offer them. On Forbes’ website it says: “More than 100 countries are exploring CBDCs at one level or another, according to the IMF. But as of 2022, only a handful of countries and territories have CBDC or have concrete plans to issue them.” However, the way people are choosing to pay for things is changing. Financial technology firms have begun to offer new forms of money and new ways to pay, and central banks (including the ECB, of course) are looking to see if it’s an avenue worth exploring. Certainly, there could be new opportunities, but also new risks. The Bank of England, for instance, is looking at the possibility of launching a CBDC of its own, which would operate alongside traditional banknotes. It has already switched to using polymer banknotes because they make counterfeiting harder, and they last longer in circulation. The Bank of England is already in talks with the Bank of International Settlements and various finance ministries to research its possible effects and how it would interlink with other countries’ economies.

The ECB points out that if the CBDC were to operate on a wholesale basis, only interacting with a limited number of financial counterparties, its effect would be minimal. It also points out, though: “However, a retail CBDC, accessible to all, would be a game changer. So a retail CBDC is now our main focus.” There remain a number of questions, such as “should it (the new digital currency) have the status of legal tender?” If not, its legal basis would require clarification. It’s been suggested that a retail CBDC could use digital tokens, but they would function very much like cash, which could mean there would be little change. The ECB has estimated that if the CBDC were to be based on deposit accounts with the central bank, it would mean increasing the number of current deposit accounts on offer from around 10,000 to a figure somewhere between 300- and 500-million. This would allow for the registration of financial transfers between users whilst offering protection against money laundering and other criminal activities. There are a lot of question that remain to be answered, including how technology could be used to facilitate it. “We do not serve technology,” the ECB writes on its website, “technology serves us.” It will certainly need to, while the rest of us will have to knuckle down and learn how to use it. As to whether or not it will offer an improved monetary system, only time will tell.