If the smugglers of one illicit substance find themselves getting cold feet, it probably means that one of their containers is leaking. You see, what they are quietly and unobtrusively trying to get into a target country are hydrofluorocarbons, or HFCs.

HFCs are organic compounds used as refrigerants and as the ‘blowing’ agent in polymer foams. You’ll also find them being used in certain types of fire extinguisher, in cleaning products and as the propellent in some aerosol sprays. Their use in extinguishing fires has become widespread.

Effectively, they remove heat, thus quenching the fire, and some can also disrupt free radicals, which can help extinguish a fire by interfering with key chemical reactions. You may recall that HFCs were welcomed onto the scene in the wake of the Montreal Protocol, which came into force in January 1989, banning the use of the even more damaging chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) that had been in use, and viewed as a miracle product, since the 1930s. CFCs, which are (for the technically-minded) halogenoalkanes, were developed following a number of fatal accidents involving the refrigerators of the time.

The first patent went to Frigidaire in 1928 and by 1935, Frigidaire and its competitors had sold some 8,000,000 new refrigerators in the United States using a CFC known as Freon-12, developed by Du Pont and General Motors under the name of their joint venture Kinetic Chemical Company. CFCs had built a deserved reputation for being non-toxic. After the Second World War, CFCs made it possible to install air conditioning in homes, cars and offices. Sounds too good to be true? It was, and the danger was only discovered years later through space research.

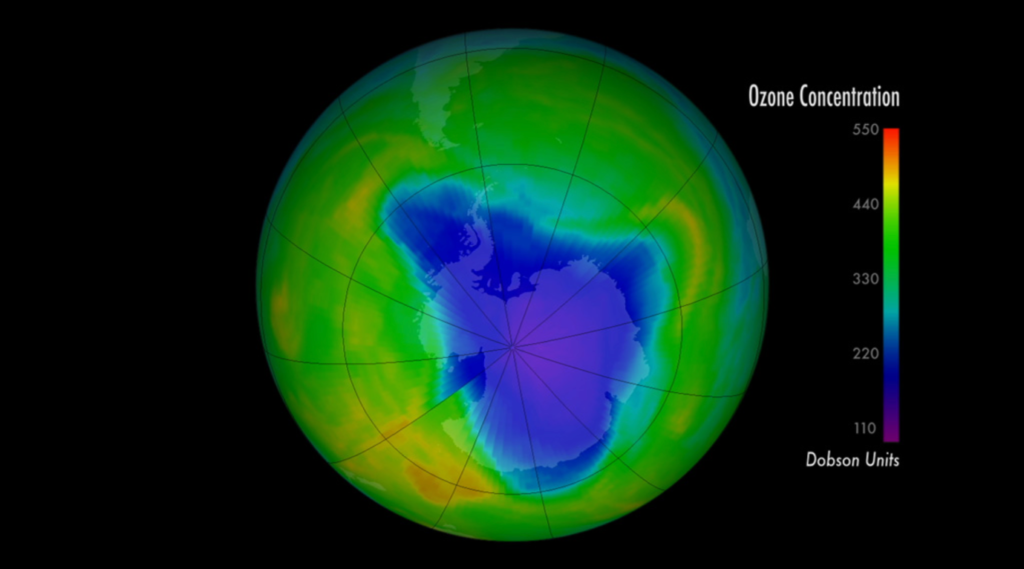

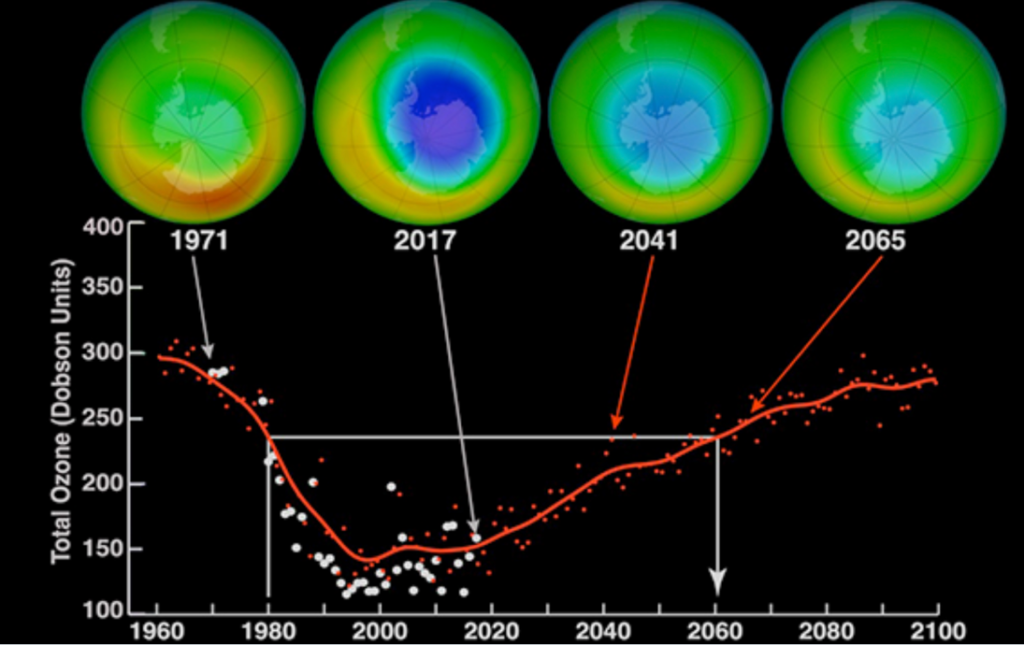

The problem is that research in the 1970s showed that inorganic chlorine radicals in the stratosphere could be the result of the photolytic decomposition of CFCs through ultraviolet radiation.

Furthermore, the inorganic chlorine released could destroy the ozone layer, which absorbs dangerous ultraviolet radiation from space, thus keeping us, the world’s wildlife and plants alive. This was further confirmed by NASA and in 1985, a hole in the ozone layer was discovered over the Antarctic. Two years later, a number of countries signed up to the Montreal Protocol to reduce the production and use of substances harmful to the ozone layer, even though some scientists still argue that ozone holes can occur naturally. We certainly know they can be caused by CFCs. Better safe than sorry, anyway: CFC-11 can last in the atmosphere for 55 years, while CFC-12, or CCl2F2, has a recognised lifetime of 140 years. The replacement chemical chosen was hydrofluorocarbon (HFC). It looked very promising and in its most useful farms, CH2FCF3, or HFC 134a, has been shown to be non-flammable and to have low toxicity. It is a big step forward from CFCs. As a result of the Montreal Protocol and the later Copenhagen Amendment, production of CFCs effectively ended in 1996.

So, everything in the garden is lovely now? Well, no: while HFCs have a zero potential to cause ozone depletion, are chemically stable, non-flammable and nonreactive, as well as decomposing in just 14 years, they can break down in the troposphere, the lowest level of our atmosphere and the place where our weather takes place, and its carbon-fluorine bonds can trap infrared radiation from the sun, redirecting it towards the surface. As a result, its potential to cause global warming (GWP) is reckoned to be 3,770 times as great as that of carbon dioxide. In other words, although our ozone layer won’t be destroyed by HFCs as it would have been by CFCs, it can roast us alive. That’s why a drastic reduction in the production and use of HFCs was called for in what’s called the Kigali Amendment to the Montreal Protocol, agreed in 2016.

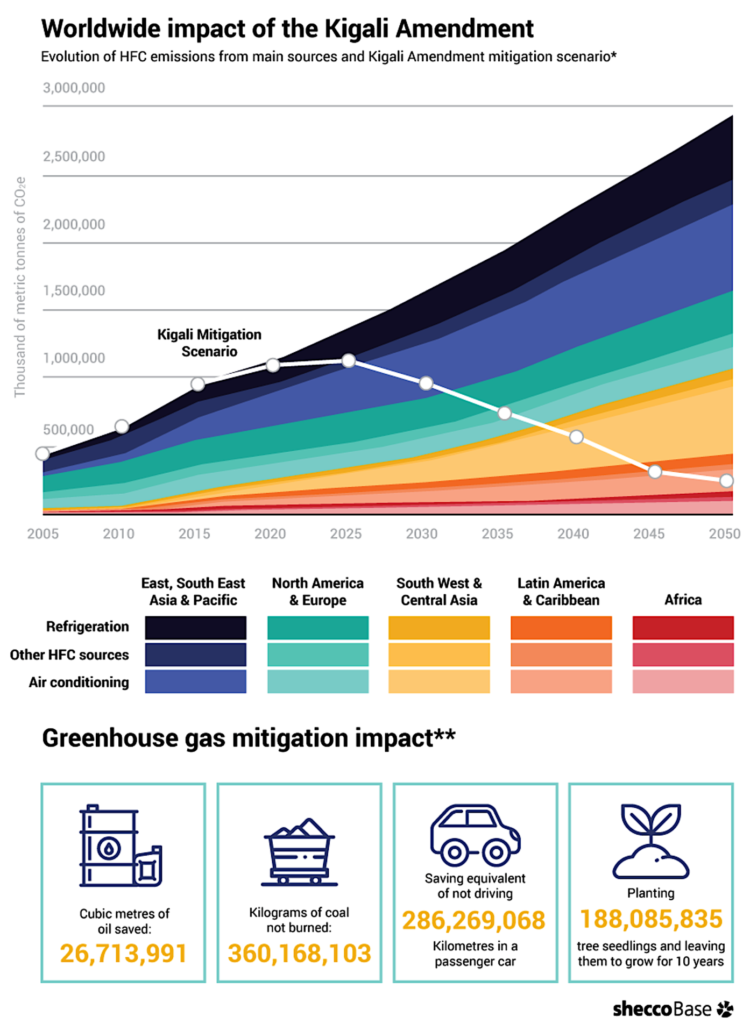

The Kigali Amendment, an agreement to phase down HFCs globally, to the Montreal Protocol was adopted by 197 parties meeting in the Rwandan capital on 15 October 2016. The Amendment sees developed countries take the lead on phasing down HFCs, starting with a 10% reduction in 2019 and delivering an 85% cut in 2036 (compared to a 2011–2013 baseline).

Entering into force in 2019, it demands a reduction of 80 to 85% by 2047, with the aim of avoiding additional global warming of up to 0.4o Celsius by the end of this century. Keeping pace with the science is a challenge, but the European Commission has set about trying to restrict access to HFCs. Under this plan, manufacturers and users of these products are supposedly incentivised to switch to more climate-friendly alternatives. “Since the introduction of the HFC quota system,” says the Commission’s website, “the European Commission has been closely monitoring its effects on the market and innovation. In the initial phase that ran until 2018, prices for the gases that do the most damage to the climate increased sharply, acting as a powerful motivation to use more climate-friendly substitutes.” Indeed, the new restrictions also acted as a powerful motivation for dishonest people to go on supplying the damaging gases, known as ‘F-gases’, by smuggling them into Europe.

STEMMING THE FLOW

The Commission opted for a quota system on fluorinated greenhouse gases with the aim of cutting the use of HFCs by 79% by 2030 (the so-called “F-Gas Regulation). It may not be quite as ambitious as the Kigali amendment’s demand for a cut of up to 85% by 2047, but it’s a step in the right direction. Sadly, the smuggling of banned refrigerants into the EU is ridiculously easy. All the criminals have to do is buy HFCs where it’s still legal to do so and then ship them across borders in a clandestine way. HFCs, even when smuggled, are very often cheaper than permitted alternatives, and the profits from the trade can then be used to fund the purchase of weapons, counterfeit goods or for people smuggling.

And according to the independent organisation, the Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA) in 2018, smuggled HFCs added the equivalent of 16.3 million tonnes of CO2 to Europe. This represented more than 16% of the 2018 quota – and is more than the total CO2 emissions of Slovenia. What’s more, how can the end user ever be sure that the HFC gas they buy is reliable or from a safe source? Analysis by Oxera Consulting LLP for the European Fluorocarbon Technical Committee (EFCTC) estimates that up to 31 million CO2-equivalent tonnes (CO2eqT) were illegally imported into the EU in 2019. This is around one third of the legal quota in 2019. Furthermore, Oxera uncovered a discrepancy of 19-million CO2eqT in 2018 between the reported exports from China to the EU and the official EU figures. There has also been a spectacular growth in export volumes from China to neighbouring countries that cannot be justified by the actual economic growth on the ground. It coincided with the EU’s clampdown on legal imports of HFCs. If it’s accurate, it would mean that an additional 34-million tonnes CO2 equivalent were being brought into the EU every year. That’s comparable, the EFCTC argues, to every one of the 1.2-million citizens of Brussels taking one trans-Atlantic flight every day for a year.

So, this is a serious, and very large problem for the planet and for its people. HFC-smuggling is not a minor offence. It encourages a range of sometimes deadly crimes and destroys Earth’s climate. Unfortunately, it’s also extremely difficult to intercept. In 2020, according to the EU’s anti-fraud office, OLAF, Italian customs authorities stopped a shipment of 300 cylinders of illicit HFC gases from entering the EU. OLAF supported the police and customs operation by providing the Italian authorities with additional information about the consignment. The importer of the consignment had no legal right to quotas and what is more the imported gases were in non-refillable cylinders, which are not allowed to be imported into the EU at all. The environmental impact of the cargo, had it reached the market, says OLAF, would have been roughly equivalent to the emissions produced by a car travelling for 35 million kilometres: around 6,800 tonnes of CO2.

“The cargo had travelled from China to the port of Livorno, Italy,” said OLAF’s website. “It contained approximately 3.7 tonnes of hydrofluorocarbon gases (HFC) and hydrochlorofluorocarbon gases (HCFC), packaged in 300 non-refillable cylinders, which are illegal in any case. Italian customs authorities identified the consignment as suspicious and seized it after verifications and information provided by OLAF confirmed its illicit nature.” Similar seizures have also been made by authorities in the Netherlands and Romania. “One positive cooperation case leads to the next,” said Ville Itälä, OLAF’s Director General. “We are happy that OLAF was able to support the Italian authorities in this successful operation, just as we did earlier in the year with our colleagues in the Netherlands and Romania. This is precisely the kind of

cooperation that we are working hard to establish between OLAF and national authorities, not only in Europe but across the globe. Such cooperation is the key to defeating the smugglers and counterfeiters, and all the more important when it helps stop dangerous gases like HFCs causing irreparable damage to our environment, health and economy.” There’s a more recent victory over the smugglers for OLAF to brag about, too.

Working together with Spanish authorities earlier this year, they dismantled a crime gang trafficking in HFCs. Operation Verbena led to the seizure of 27 tonnes of illicit refrigerant gases, or F-gases, and to the arrests of five people. It was the biggest such operation yet at EU level, and apart from the seizures, investigators discovered a further 180 tonnes of illicit HFCs that had been smuggled earlier. It’s now thought the gang involved may be responsible for emissions of more than 234,000 tonnes of CO2-equivalent gases into the environment, the equivalent, say OLAF, of a car driving all the way around the world 9,000 times.

The Spanish Police, in a statement to the media on-line, said: “It is the largest European operation carried out to date against greenhouse gas fraud, having intercepted more than 27,000 kilograms of fluorinated gases and discovered more than 180,000 more. Five people have been arrested as alleged members of a complex business network that acted in violation of community regulations, causing the emission of tons of gases into the atmosphere without authorization.” Being an HFC smuggler, then, while relatively easy for some, is not without its risks.

A CONFUSION OF GASES

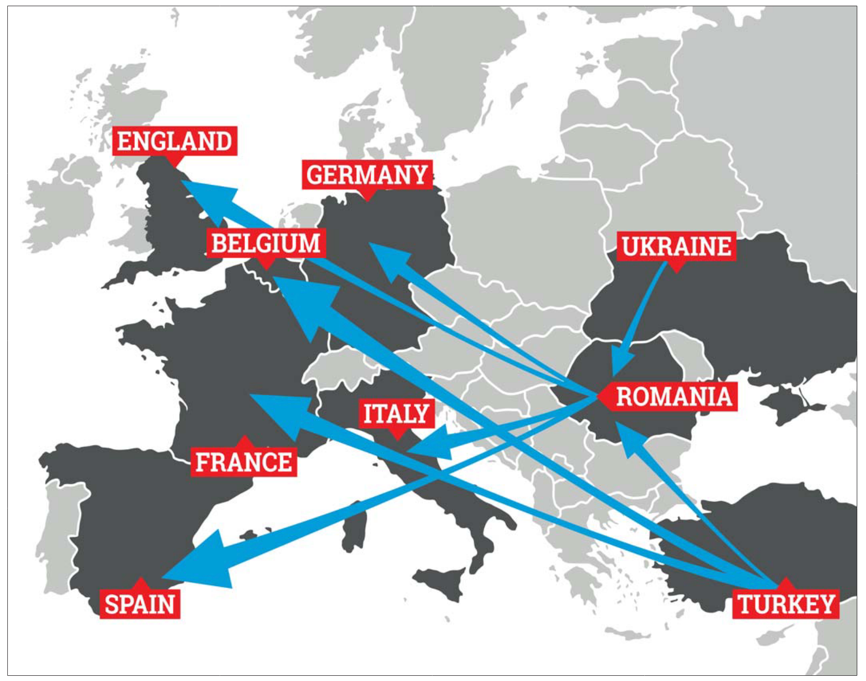

OLAF, together with others, has been monitoring the routes the traffickers use to get their illicit shipments into the EU. They found two main routes into Romania being used, one directly from Ukraine and one from Turkey, going via Bulgaria. One of the routes involved several Romanian companies buying large consignments that had arrived in Turkey from China. These were then divided up before onward transportation to Romania. Romanian customs officers, though, succeeded in intercepting 76-tonnes that were being taken from Turkey to Romania, where 5 companies had placed an order. One of them – but only one – had an EU quota for buying HFC gas legally. According to the EIA, 83% of those working in the refrigeration sector are aware of the illegal traffic in HFCs and a surprising 72% have been offered disposable gas cylinders, even though they are banned in Europe. Not only does the use of smuggled and illegal HFCs endanger the environment, it also undercuts legitimate enterprises and allows unfair competition for those companies that are abiding by the law.

The immediate aftereffect of the EU’s “Phase Down” of HFCs, as it was called, saw little change in prices. However, according to a European Commission report, from mid-2017 onwards, prices for some of the potentially damaging gases started to rise dramatically, reaching a peak in early 2018 at 6 to 13 times their original prices. The more potent (and dangerous) the gas, the higher the price, it seems. Even so, the prices never quite reached the level that had been assessed as ‘appropriate’: €50 per tonne, CO2 equivalent. There were also reports of legally-obtained HFCs being in short supply for those still using them, especially in Germany, Italy and Spain.

The one that was hardest to locate was an HFC called R404a, which has a high Global Warming Potential (GWP) and is already discontinued by many suppliers, having been banned in new applications, although I found it for sale on a UK website offering a 70% discount. Only reclaimed R404a, extracted for re-use from existing equipment, is permitted under EU rules to service pre-existing equipment and only until 2030. It is used in industrial and commercial refrigeration and also in transport refrigeration. Two more HFCs are R134a, which is widely used in car air conditioning and servicing, and R410a, which may be being used in the EU to produce air conditioning equipment, although it cannot be retrofitted to equipment designed to operate with R22 refrigerant because it is used at a higher pressure.

Just in case you’re wondering what, in this wonderful world of organic chemistry, R22 is, I shall tell you: it is known more correctly as chlorodifluoromethane or difluoromonochloromethane, (such long names must complicate the labelling of containers) and is a hydrochlorofluorocarbon, better known as HCFC-22, or R22, or CHClF ₂. It has been commonly used as a propellant and refrigerant, but officially not anymore. This means that if your air conditioning system was built with R22 as the refrigerant, you can go on using it but it will be hard to replace worn out parts and completely impossible to refill it with R22. It sounds complicated, even confusing, but the aim is to lower the average GWP of the gases supplied to the refrigeration industry.

THE FUTURE IS CHOCOLATE

Of course, though, air conditioning and refrigeration are not the only uses to which refrigerant gases have been and are still being used. According to the American Chemical Society’s fascinating and surprisingly accessible website, “a survey of 1,000 U.S. adults conducted for Honeywell earlier this year by ORC International (Opinion Research Corporation International) found that more than 100 people thought spray chocolate was a good idea.

Over 80 people liked the notion of spray ketchup.” What about global warming? It seems personal convenience usually comes first. “While the unusual proposals for aerosol condiments didn’t get a stellar reception, the opinion research experts at ORC did find that 93% of those surveyed use aerosol products in some capacity. Hair spray, deodorant, paint, cooking oil spray, flat tire filler, shaving cream, and bug bombs are just some of the many aerosol products out there.” So, there you are: would you give up spray chocolate to save the planet? Clearly, for many people the answer is ‘no’. In the rich smorgasbord of available industrial gases, what’s left? HFC134a is one. It’s a 1,1,1,2-Tetrafluoroethane, which was introduced in the early 1990s as a replacement for dichlorodifluoromethane (R-12), which seriously depletes the ozone layer. Or how about HFC152, known to its friends as 1,1-Difluoroethane, or DFE, an organofluorine compound with the chemical formula C2H4F2. It is often used as a propellant in aerosol sprays because it is impossible for it to harm the ozone layer, a low GWP and a short atmospheric lifetime of just 1.4 years. I shouldn’t be flippant about this because it matters. We have a choice, once the business of converting to less harmful means of refrigeration has been sorted out, between satisfying our desire for – let’s face it – unnecessary fripperies and the continued existence of a habitable planet. “Want to save the planet from destruction?” “No, let’s spray our tongues with chocolate instead!”

The European Commission is fairly happy with the way things have been developing. Between 2015 and 2018, the total amount of HFCs supplied to the EU market (including in such equipment as air conditioners) dropped by 37% in CO2 equivalent, although the drop in volume was only 25%. This is thought to represent a shift in supply towards HFCs with lower GWP and other alternatives. There is a “but” in here, though. There has been a fragmentation of the supply chain, with traditional suppliers losing market share to new competitors. Five or so years ago, there were just over 100 companies supplying the gases, some of them large and dominant. Now there are some 2,500, many of them holding only small quota rights, with transfers within groups becoming common. The number of players involved means more paperwork and transaction costs have inevitably impacted on end prices. It has also made the job of policing the imports to ensure the exclusion of illegal gases more difficult.

The situation has reached the stage at which the 57 companies involved in using the gases in question are seriously worried. Their representative body, the EFCTC, wrote to the European Commission in May 2021 requesting a tougher clamp-down on the black market in HFCs that has sprung up. “New data released in February 2021 show that this illegal market continues to bypass the EU F-gas regulation quota system which has been in place since 2015,” the letter reads. “Research by Oxera Consulting LLP, analysed by EFCTC, shows that the black market was thriving in 2019. Up to an estimated 31 million CO2eqT (CO2 equivalent tonnes) could have entered through EU borders illegally.” The assessment of the current situation is clearly not favourable, but the letter predicts worse to come. “2021 is marking a new phase-down step, as the F-gas regulation2 sets a reduction of the quota from 63% to 45% compared to pre-2015 level. As a result, we anticipate an increase in illegal imports of HFCs this year.” The EU’s understaffed and mostly underfunded customs services look like having a tough time of it, despite the successes justifiably boasted about by OLAF. The letter wants the Commission to promote best practices by ensuring that customs authorities have access to the “necessary information and tools”. At present, customs officers can check if an importer has an import quota, but not how much has already been imported. The letter also wants to see tougher fines for offenders and better cooperation with OLAF, Europol and others in order to gather evidence and collect additional data on just how big the illegal market may be. If legitimate and highly-regarded operators in this sector want to see tougher laws being applied, it suggests that something is seriously wrong.

The plain fact is that HFCs (and even some CFCs) are essential in the pharmaceutical industry. For instance, inhalers for asthma sufferers still use inhalers powered by CFCs, although their use has been severely reduced since it was discovered how much damage they can do to the ozone layer. For many years, chlorofluorocarbon propellants were used in most aerosol products, but since 1996, their use has been limited to aerosols needed in the treatment of asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Gases are also used in the production of foam products.

Azodicarbonamide (ADA), for instance, used to be called ‘the yoga mat’ gas, because of its use in creating foam rubber of the type used in the production of yoga mats. The main product of azodicarbonamide decomposition is nitrogen, along with some CO2, CO (carbon monoxide) and NH3 (ammonia). It’s also a chemical substance that has been approved for use as a whitening agent in cereal flour and as a dough conditioner in bread baking, although such a use has been banned in, for instance, Australia and the EU because it’s thought that it may be carcinogenic. For blowing bubbles in foam products, HFCs have provided an alternative, albeit not for much longer, probably.

I’M NOT FOREVER BLOWING BUBBLES

The idea behind what’s called a ‘blowing agent’ is a chemical that can produce a cellular structure, such as foams and packing materials, which can reduce the weight of a product as well as giving it extra rigidity. CFCs, of course, were for many years the ‘go-to’ material until the Montreal Protocol in 1987. They were initially replaced with HCFCs – chlorodifluoromethane or difluoromonochloromethane – but as these also deplete the ozone layer, albeit not quite so badly, they are also being phased out. The differences between CFCs and HCFCs will mean more to chemists than to the rest of us. The key difference between CFC and HCFC is that the CFC contains only carbon, fluorine and chlorine atoms whereas HCFC contains hydrogen, carbon, fluorine and chlorine atoms. More importantly, CFC causes serious ozone depletion but HCFC, comparatively, has much less of an impact on the ozone layer. It’s still bad enough to get it phased out, however.

CFCs are a class of compounds containing fully halogenated paraffin hydrocarbons. “Halogenated” simply means using a process involving the addition of a halogen halide molecule or the substitution of a halogen atom in an organic (carbon containing) compound. “HCFCs are less stable than CFCs because HCFC molecules contain carbon-hydrogen bonds,” explains the Global Monitoring Laboratory on its website. “Hydrogen, when attached to carbon in organic compounds such as these, is attacked by the hydroxyl radical in the lower part of the atmosphere known as the troposphere. (CFCs, because they contain no hydrogen, and, therefore, no carbon-hydrogen bonds, are not destroyed by the hydroxyl radical.) When HCFCs are oxidized in the troposphere, the chlorine released typically combines with other chemicals to form compounds that dissolve in water and ice and are removed from the atmosphere by precipitation. When HCFCs become destroyed in this way their chlorine does not reach the stratosphere and contribute to ozone destruction.” HCFCs, then, are less destructive than CFCs, but they’re by no means good for the planet. Most of the depletion of ozone is caused when chlorine or bromine, a halogen found in seawater, reach the stratosphere, and 84% of the chlorine entering the atmosphere comes from man-made sources, such as CFCs and HCFCs, with the remaining 16% coming from natural sources, such as the sea and from volcanoes. Roughly 50% of the bromine entering the atmosphere also comes from man-made sources, mostly halons.

BETTER, BUT NOT BEST

Some of the HCFC molecules released into the atmosphere eventually get to the stratosphere, where they are destroyed by photolysis (the breaking of a chemical bond by the impact of a photon). The chlorine thus released in the stratosphere can then take part in reactions that may damage the ozone layer. HCFCs, however, are significantly degraded by two atmospheric mechanisms, unlike CFCs, which are destroyed virtually completely in the stratosphere by photolysis, but because photolysis rates for HCFCs are generally slower than those for CFCs, proportionately less chlorine is released when compared to CFCs. These properties explain why HCFCs are expected to deplete much less stratospheric ozone than equivalent amounts of CFCs. They are, however, still destructive; research into air trapped decades ago, far from habitation or industry, shows that concentrations of HCFCs have grown rapidly in recent years.

As explained above, about half of bromine entering the stratosphere is from man-made sources, mostly halons, which can be any of a group of organohalogenic compounds containing bromine, fluorine and one or two carbons. If you’re wondering why protecting the ozone layer matters so much, Ozone is the Earth’s shield against harmful levels of ultraviolet (UV) rays from the sun. Without it, life would be almost impossible, with many of us suffering skin cancers, cataracts, and damaged immune systems. That’s why getting tough with the smugglers is important. Europol show information on their website about one large-scale success in 2019, in which Spanish authorities uncovered an organised crime group involved in the illegal trade.

The specialised Environment and Urban Planning Unit of the Spanish Public Prosecutor’s Office coordinated the Nature Protection Service of the Spanish Civil Guard (Guardia Civil) to carry out the investigation, supported by Europol and the French National Gendarmerie (Gendarmerie Nationale). The investigation revealed that a company in Valencia, Spain, was involved in smuggling ten tons of R22 (chlorodifluoromethane) refrigerant gas without a legal licence, bringing in a profit of between €500,000 and €1-million for the gang. The Europol website says that “Police launched their investigations in 2017 when the Spanish Ministry of Environment was informed of R22 gas allegedly being exported to Panama illegally. The operation disclosed that the company repackaged R22 refrigerant liquids that should have been sorted as hazardous waste. This led to around 10,000 kg of R22 gas being traded illegally as regenerated gas. The investigation revealed that these ten tons of illegally exported gas would have released (the equivalent of) 17,000 tons of CO2 into the atmosphere.” Next time you get sunburned, blame the criminals.

It is not a victimless crime; we are all victims. Yes, certainly, legitimate businesses are suffering but at the end of the day we all are, and it is seriously impeding Europe’s attempts to be more climate-conscious. Criminal gangs have spotted an opening through which to make extra money, without regard to the people they hurt along the way. The potential climate impact of this illegal trade could amount to the greenhouse gas emissions of more than 6.5 million cars being driven for a year.

“The most shocking revelation,” said the EIA on its website, “was the discovery that these hazardous gases were being smuggled around Europe below unwitting passengers and drivers in the luggage compartments of transcontinental coaches, among other methods.” Crooks only care about money, of course, even those who regularly attend churches of various kinds. Clare Perry, EIA’s Climate Campaigns Leader, said on the organisation’s website: “It’s no exaggeration to say the future stability of human society sits on a knife-edge and time is running out to meaningfully tackle climate change. We can’t afford a single misstep in our efforts to keep the global temperature rise below 1.5°C and the sheer scale of illegal HFC trade into the EU should be ringing alarm bells throughout the bloc – this is the biggest eco-crime no-one’s heard of and that needs to change, fast.” There’s no sign of that happening, unfortunately. The EIA identified a growing trend of illegal HFC-404A in circulation, a super-potent refrigerant that is banned from topping up large refrigeration systems. In 2020, this refrigerant accounted for more than one-third of all HFC seizures. R404A is an HFC blend, intended as a replacement for R22 and R502, but it is regarded as having as high potential for global warming. As a result, attention being increasingly focused on lower GWP alternatives, such as R407F and R407A, along with newer options like R448A and R449A, which are non-toxic and non-flammable refrigerant blends that closely match the properties of R404A.

The world is warming, and if the EU is to try and save it on behalf of us all, it will need all the help it can get. Just remember that the same criminals may also be engaged in trafficking drugs, guns and people. They’re not nice people. We would be breathing cleaner air without them.