© EDM

Across Europe, from the icy fjords of Norway in the far north to the sunny shores of the Mediterranean, a chilling realisation is settling in: the era of American protection may be coming to and end.

Since the end of World War II, Europe has relied on the United States as its ultimate security guarantor, a shield against the spectre of Russian aggression. But now, as geopolitical tides shift and America’s attention outside its own borders turns increasingly toward the Indo-Pacific, Europe finds itself staring into an abyss of uncertainty. The question is no longer hypothetical—it is urgent and existential: Can Europe defend itself without the United States, especially as China and Russia forge closer ties?

The warnings have been unrelenting, and often, stark In early 2024, top military and political leaders across Europe began sounding the alarm about the possibility of war with Russia within the next three to eight years. The then heads of the Swedish Armed Forces, and the British Army, both called for civilian preparedness, while the German defence minister warned of a five-to-eight-year window before conflict erupts. Estonia’s prime minister was even more dire, predicting a three-to-five-year timeline.

Let us pause to reflect on the precarious and increasingly volatile situation in which Europe now finds itself. The geopolitical landscape is undergoing profound shifts, and the challenges facing the continent are both urgent and multifaceted. Russia’s continued belligerence shows no signs of abating, while Ukraine’s position, despite its remarkable resilience, continues to deteriorate under the weight of prolonged conflict. Compounding these tensions are Donald Trump’s objections to the US payting the lion’s share of the cost of this war. The questions we must confront are not merely academic or speculative—they are existential. At the heart of the matter lies not only the risk of the United States abandoning Ukraine but also the far more unsettling prospect of America disengaging from Europe altogether.

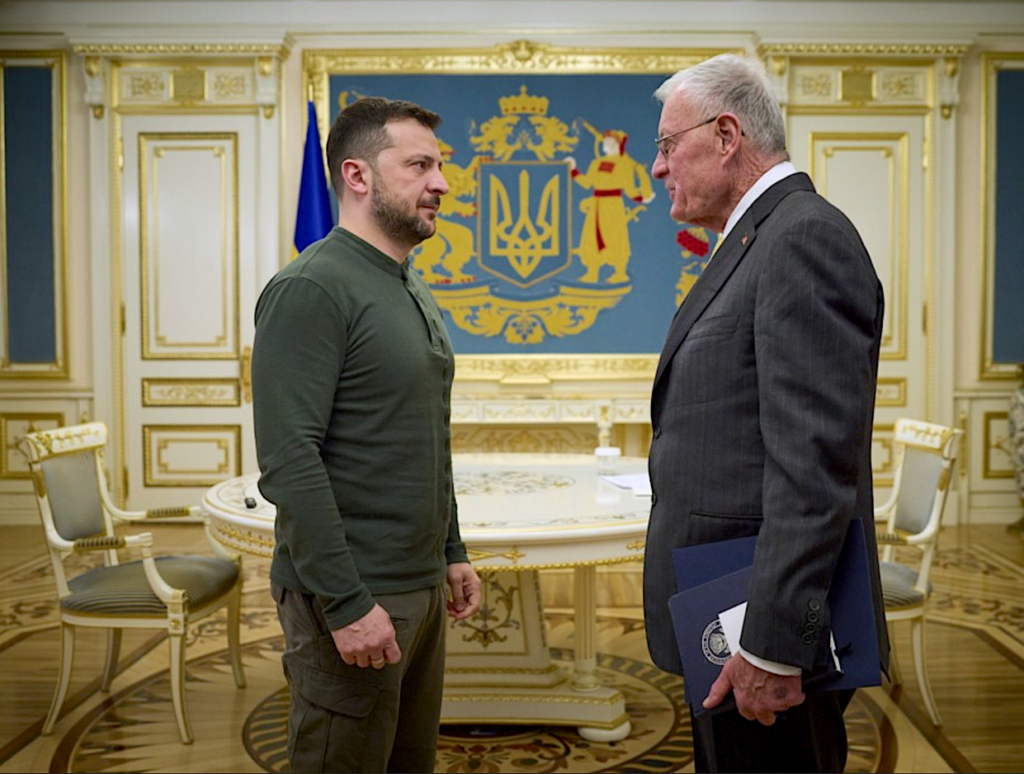

On 19 February, Keith Kellogg, the American president’s special envoy arrived in Kyiv with the perceived goal of supporting Ukraine and President Zelensky, ‘We understand the need for security guarantees,’ Kellogg told journalists, saying that part of his mission would be ‘to sit and listen’. But as all this was going on, Donald Trump made a statement that sent yet more shockwaves across Europe; he blamed Ukraine for the war with Russia, contradicting international consensus and raising more concerns about the commitment of U.S. policy. Following the meeting in Saudi Arabia between the U.S. Secretary of State, Marco Rubio and the Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov, Trump brushed off Ukraine’s concern about being left out of the talks and even suggested that Kyiv could have settled the conflict with Russia sooner.

These conflicting messages left European allies deeply unsettled, raising doubts about the consistency and commitment of U.S. policy. This only added to growing concerns over the future of Western solidarity in confronting Russian aggression.

Should a significant disengagement on the part of the U.S. occur, Europe would face the monumental task of redefining its role in global security. Merely increasing defence spending, while most necessary, would be insufficient to address the scale of the challenge. Europe would need to undertake a comprehensive transformation of its defence capabilities. This would involve revitalising its arms industry, which has weakened over the years due to underinvestment and fragmentation. It would require the creation of a new nuclear deterrent framework to replace the security umbrella historically provided by the United States.

Additionally, Europe would need to establish a cohesive and efficient command structure capable of unifying its diverse military forces and coordinating large-scale operations. These are not minor adjustments; they are foundational shifts that would demand unprecedented levels of political will, strategic foresight, and collective action.

The urgency of this moment cannot be overstated. The question is not only whether Europe is capable of rising to the occasion but whether it can do so rapidly and decisively enough to avert a crisis. The stakes are nothing short of the continent’s security, stability, and future role on the global stage.

| THE GATHERING STORM: A CONTINENT AWAKENS

The United States, long Europe’s protector, is turning its attention elsewhere. Beyond the Middle East and particularly Israel and Gaza, where President Trump has expressed a particularly sharp interest, the rise of China as a global superpower has reshaped American priorities. Both Democrats and Republicans today agree that the Indo-Pacific is now the primary theatre of strategic competition, and even if the U.S. remains nominally committed to NATO, its military resources are being redirected to Asia. The days of America’s unconditional commitment to Europe’s defence seem to be well and truly over.

As Europe grapples with the prospect of American disengagement, a new and more ominous threat looms on the horizon: the deepening alliance between China and Russia. While historically wary of each other, the two powers have increasingly found common cause in challenging the U.S.-led global order. This rapprochement is not merely political but also military, with joint exercises, technology transfers, and strategic coordination becoming more frequent.

China’s growing military capabilities, particularly in areas like cyber warfare, missile technology, and naval power, complement Russia’s strengths in conventional land forces and nuclear deterrence. Together, they present a formidable challenge to Europe. For instance, China’s advanced drone technology and electronic warfare capabilities could bolster Russia’s already significant advantages in these areas, tipping the balance further against Europe.

Donald Trump’s return to the White House has only heightened Europe’s anxieties, as he has continued to question the value of NATO; his administration could accelerate America’s disengagement from Europe. His vice-president, J.D. Vance, represents a faction that believes Europe must take up the burden of its own defence. The message is clear: Europe must no longer depend on America’s generosity. During his much-anticipated speech at NATO headquarters in Brussels in February, Defence Secretary Pete Hegseth said: ‘The United States will no longer tolerate an imbalanced relationship’ regarding the war in Ukraine and ‘would not be taken for Uncle Sucker!’.

The United States is, in fact, the largest global contributor to defence spending, allocating a staggering $967.7 billion, which represents 3.38 per cent of its Gross Domestic Product (GDP). This figure far surpasses the defence expenditures of any other nation.

| ‘DIG INTO YOUR POCKETS!’

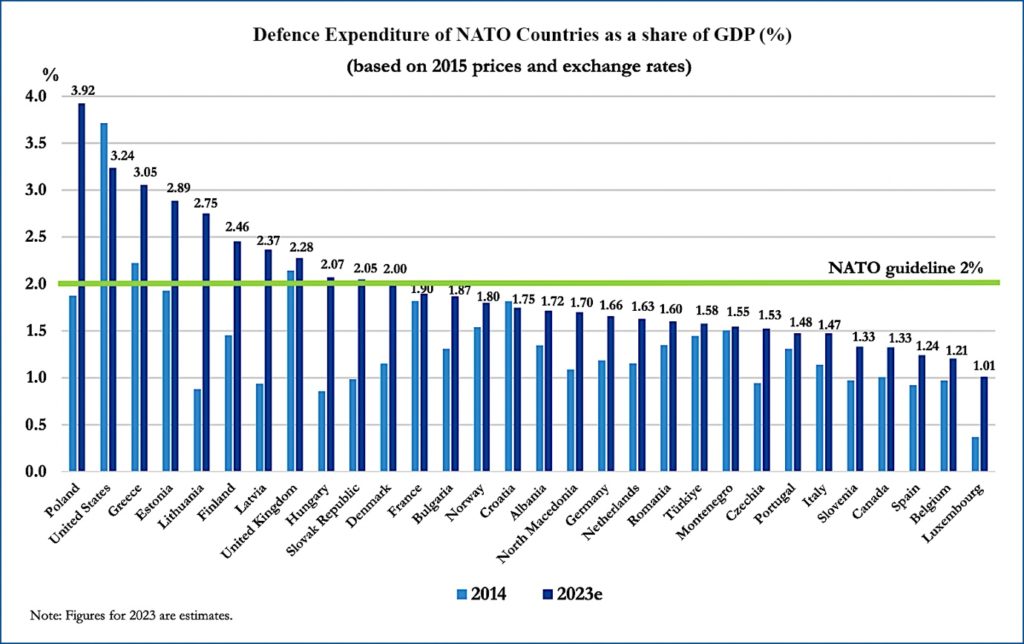

After Russia’s takeover of Crimea in 2014, NATO members pledged to allocate 2 per cent of their GDP to defence spending in order to bolster the alliance’s military preparedness. However, by 2024, only 23 out of the 32 member states had met this target. Beyond individual defence budgets, the financial burden of NATO’s overall budget is unevenly distributed, with the top ten contributors bearing the lion’s share of the costs.

The United States and Germany are the largest net contributors, each covering approximately 15.9 per cent of NATO’s €4.6 billion budget for 2025. The United Kingdom follows closely as the third-largest contributor, accounting for 11 per cent of the budget, or roughly €503 million. France and Italy come next, contributing 10.2 and 8.5 per cent, respectively. On the other end of the spectrum, smaller nations like Albania, North Macedonia, and Montenegro contribute less than 0.1 per cent each, with their GDPs representing a fraction of the U.S. economy.

This disparity in contributions has long been a point of contention, particularly for figures like Donald Trump, who has repeatedly urged NATO members to increase their defence spending. In March 2024, Trump made the exaggerated claim that the U.S. funds 90 to 100 per cent of NATO’s budget, warning that the alliance would not survive without American support. He also suggested that the U.S. would only defend member nations if they significantly boosted their financial commitments.

Trump’s recent actions have further rattled NATO allies. In February, he announced that he had spoken directly and at length with Russian President Vladimir Putin, without consulting European leaders, announcing plans to initiate a peace process. This move, coupled with his calls for NATO members to raise defence spending to 5 per cent of GDP, has left many European nations uneasy about the future of the alliance and America’s role within it.

In response to Donald Trump’s calls for Europe to take greater responsibility for its own security, NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte emphasised that member nations currently spending around 2 per cent of their GDP on defence should aim to push that figure ‘above 3 per cent.’ Speaking at a meeting of NATO defence ministers in Brussels, Rutte urged European allies to increase their contributions, stating, ‘Spend more, spend more. Those not at 2 per cent need to get there by this summer, and those already at 2 per cent must prepare for much, much more—north of 3 per cent.’

Rutte acknowledged two key factors driving this push: the U.S’s. need to focus on multiple global conflict zones and the ongoing frustration among American leaders about Europe’s reliance on U.S. defence spending. ‘The U.S. has every right to be extremely irritated,’ he said, adding that increased defence spending might require higher taxes, a reality the U.S. also faces. ‘When you spend 3.5 per cent on defence, that’s money you can’t spend on pensions or tax cuts,’ he noted.

French Armed Forces Minister Sébastien Lecornu shared similar concerns, emphasising the importance of NATO allies planning for the future and boosting their defence industries. Speaking to reporters before the Brussels meeting, Lecornu said, ‘This is a critical moment of truth. NATO has always been the strongest military alliance, but will that still be the case in 10 or 15 years?’

The war in Ukraine has also led to calls for a major rethink of NATO’s purpose. U.S. Defence Secretary Pete Hegseth, called this a ‘factory reset’ moment for the alliance, stressing that NATO needs to become ‘tough, strong, and effective’. He backed Trump’s push for allies to increase defence spending to as much as 5 per cent of GDP, though he added this could be done step by step. ‘Two percent isn’t enough. Three, four, and eventually five percent is crucial,’ Hegseth said. ‘Facing down Russia’s military aggression in Ukraine is a key responsibility for Europe.’

Whichever way this goes, European nations recognise that U.S. support will remain critical for the foreseeable future, and building up defence production and integrating forces into an effective system will take years. ‘U.S. security guarantees are essential for lasting peace’, stressed UK Prime Minister, Keir Starmer before adding, ‘Only the U.S. can deter Putin from further aggression’.

While European countries are committed to backing Ukraine and boosting defence spending, hitting even the 3 per cent target is no easy task. Some EU members are pushing for shared borrowing to finance major defence initiatives, while others argue that countries falling behind need to hit the 2 per cent mark first. This tricky debate is likely to dominate discussions at stage at upcoming rounds of meetings.

| EUROPE’S DEFENCE DEFICITS

The 2025 Munich Security Conference concluded with a sobering assessment of the global security landscape, reflecting the deepening geopolitical fractures and the urgent need for collective action. The war in Ukraine remained a central topic, with calls for sustained Western support. However, there was also a recognition that Europe must prepare for a prolonged conflict and the possibility of further Russian aggression against NATO’s eastern flank, which of course, includes the Baltic States. In summary the conference painted a picture of a world at a crossroads, with Europe facing unprecedented challenges and the need to adapt rapidly to a shifting geopolitical order. The conference also served as a wake-up call for greater unity, investment, and innovation in addressing both traditional and emerging threats.

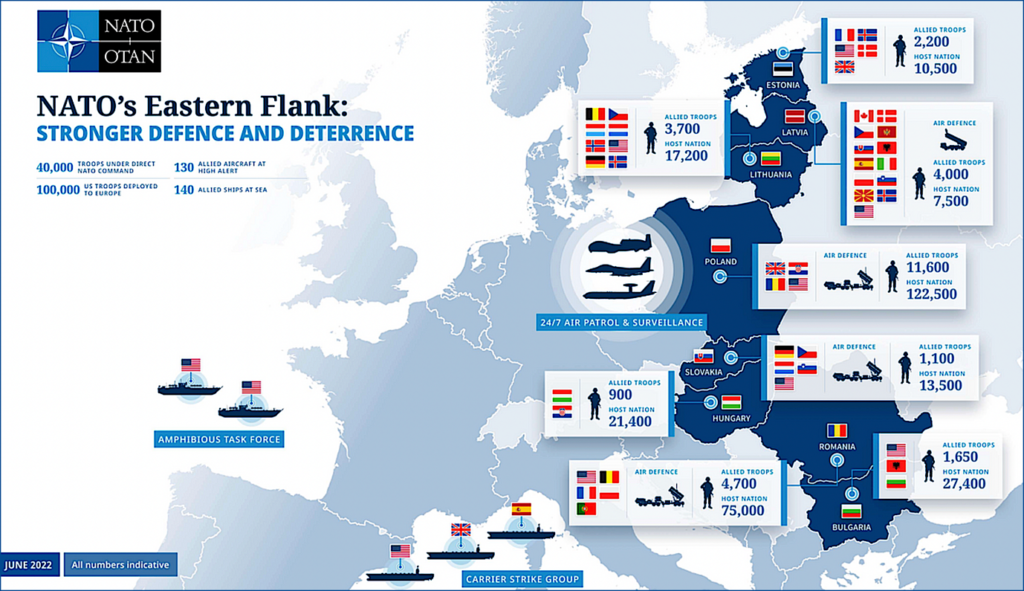

Europe’s military strength looks impressive on paper, but it’s full of gaps. Together, European NATO countries have more tanks, armoured vehicles, and troops than Russia. But these forces are spread across many nations, making it hard to coordinate and work together effectively in a crisis. Russia, on the other hand, has a unified command, lots of real-world combat experience, and a growing stockpile of modern weapons.

A major weak spot for Europe is in the area of air defence. It has only about a third of the air defence systems that Russia has, leaving it far behind in this crucial area. While Europe’s defence industry is advanced, it has been slow to increase production. On top of that, Europe depends heavily on American support—like air refueling tankers, spy satellites, and communication systems—which highlights just how exposed it really is.

As far as military capabilities are concerned, when a comparison is made, it becomes clear that both the European Union and Russia possess significant strengths, but they differ fundamentally in structure, priorities, and effectiveness.

The EU, as a collective of 27 member states, boasts a large number of active military personnel spread across its nations, but this strength is often fragmented, with defence spending varying widely between countries. While the EU’s combined defence expenditure is substantial, many member states still fall short of the NATO target of spending 2% of GDP on defence. Additionally, the EU’s advanced defence industries and cutting-edge technology are somewhat hampered by slow production rates and challenges in coordinating efforts across multiple nations.

Efforts like the European Defence Fund (EDF) aim to improve collaboration, but progress remains gradual. And, as we have seen, the EU relies heavily on NATO, particularly the United States, for critical capabilities such as air defence, intelligence, and logistical support.

EIn contrast, Russia maintains a large, centralised military force with a high level of readiness and significant battlefield experience gained from recent conflicts in Syria and the ongoing war in Ukraine. Russia spends a much larger percentage of its GDP on defence compared to most EU countries, prioritising military modernisation and expansion. Its unified command structure allows for quicker decision-making and deployment, giving it an edge in operational efficiency.

Furthermore, Russia possesses one of the world’s largest nuclear arsenals, providing a formidable strategic deterrent that far exceeds the capabilities of individual EU nations, though France and the UK maintain their own nuclear forces.

So, for the EU to fully realise its potential, it would need to address these disparities by improving coordination, increasing defence investment, and reducing dependence on the United States. Until then, the balance of military power between the EU and Russia remains asymmetrical, with each side excelling in different areas.

| THE NUCLEAR THREAT

One of the toughest challenges for Europe is replacing something everyone hopes will never be used: America’s nuclear protection. The U.S. has long pledged to defend its European allies with its nuclear arsenal, including both long-range strategic weapons and smaller, shorter-range B61 gravity bombs stored in Europe, which can be dropped by European aircraft. These weapons have long been the ultimate safeguard against a Russian invasion. But if an American president were unwilling to send troops to defend a European ally, it’s hard to imagine they would risk American cities in a nuclear confrontation with Russia.

During Donald Trump’s first term in office, this concern reignited an old debate about how Europe could make up for losing America’s nuclear shield. Britain and France both have their own nuclear weapons, but together they only have about 500 warheads—far fewer than America’s 5,000 or Russia’s nearly 6,000. Some argue that even a few hundred warheads are enough to deter Vladimir Putin, as they could still destroy Moscow and other major cities. But others worry that the huge gap in nuclear firepower—and the devastating damage Britain and France would face in return—gives Putin a significant edge in any nuclear standoff.

The issue of nuclear weapons touches on the most important questions of sovereignty, identity, and survival, highlighting the void that would be left if America were to step back from Europe. In 1994, during a period of reflection on Europe’s defence and security architecture, particularly in the context of post-Cold War uncertainties, French President François Mitterrand famously said, ‘A European nuclear doctrine and deterrent will only exist when there are vital European interests, recognised by Europeans themselves and understood by others. We are far from that point.’

Europe has made progress towards greater unity in defence, but it still falls short of achieving a fully cohesive strategy. The lingering doubts that once drove individual nations to develop their own nuclear capabilities—like France in the 1950s—now echo across the continent in a different form. For instance, would a leader in Western Europe be willing to risk their own cities to protect a smaller ally on the eastern flank? This mirrors the age-old question: would an American president ever risk their own homeland to defend a European ally?

This enduring uncertainty, rooted in questions of trust and shared sacrifice, complicates efforts to create a truly unified European defence framework. It underlines the delicate balance between national interests and collective security, making it harder to forge the kind of solidarity needed to address today’s geopolitical challenges. Until these doubts are resolved, building a stronger, more integrated European defence strategy will remain an uphill battle.

| THE PATH FORWARD

Europe faces a critical moment in strengthening its defence capabilities, and according to many military experts and analysts who study European defence and security, several key steps are needed to address vulnerabilities and prepare for future challenges. Europe’s defence industry must shift from peacetime production to a wartime mindset. Countries like Germany and Poland are already taking steps in this direction, investing in new production lines for ammunition and advanced weapons. Collaborating with allies such as South Korea and Japan could further boost Europe’s industrial capacity, ensuring it can meet the demands of a more dangerous world.

In recent years, Poland has launched the largest modernisation programme for its armed forces in history. In July 2024, Deputy Minister of National Defence Paweł Bejda stated that it was his “dream” for Poland’s defence budget to increase to 5% of the country’s GDP. According to official statistics, Poland is already spending 4% of its GDP on defence, with 3% from the Ministry of National Defence’s budget and 1% from the Armed Forces Support Fund (FWSZ). In 2023, a total of EUR 25.8 billion was allocated to defence, which is 51% more than in 2022

In recent years, Poland has launched the largest modernisation programme for its armed forces in history. In July 2024, Deputy Minister of National Defence Paweł Bejda stated that it was his “dream” for Poland’s defence budget to increase to 5% of the country’s GDP. According to official statistics, Poland is already spending 4% of its GDP on defence, with 3% from the Ministry of National Defence’s budget and 1% from the Armed Forces Support Fund (FWSZ). In 2023, a total of EUR 25.8 billion was allocated to defence, which is 51% more than in 2022

Second, Europe’s military forces, which are currently fragmented across many nations, need to be better integrated. While the EU’s mutual assistance clause (Article 42.7) provides a legal foundation for collective defence, turning this into reality requires stronger political will. Initiatives like multinational brigades and joint procurement programmes could help improve coordination and ensure that European forces can work together effectively in a crisis.

Third, Europe must focus on building up critical capabilities where it currently falls short, such as air defence, electronic warfare, and drone operations. Developing its own expertise in these areas would reduce reliance on American support and give Europe greater independence in addressing emerging threats.

Fourth, Europe’s armed forces are struggling to attract new recruits, a problem made worse by changing cultural attitudes an d declining interest in military service. To address this, governments will need to work hard to restore the prestige of military careers and reignite a sense of national duty among younger generations.

Finally, even as Europe works to strengthen its own defences, it must carefully navigate its relationship with the United States. NATO remains essential to European security, and the alliance must adapt to new geopolitical realities. This means addressing American concerns about fair burden-sharing while also preserving the strong transatlantic bond that has underpinned European security for decades.

The path ahead is tough and uncertain, but it also offers countless openings. Europe has the wealth, technology, and human capital to defend itself. What it seems to lack is the political will to make hard choices and the strategic vision to chart a new course.

The stakes could not be higher. If Europe fails to act, it risks becoming a pawn in the great power rivalry between the United States and China, or worse, a battleground in a resurgent Russia’s imperial ambitions, bolstered by Chinese support.

Europe can no longer afford to be passive. It must step up and act, not only for its own survival but to protect the principles of a free and open world. The question is not whether Europe can defend itself—it is whether it will.

The answer will decide Europe’s future and set the tone for what comes next.

hossein.sadre@europe-diplomatic.eu