Russia’s T-14 tank

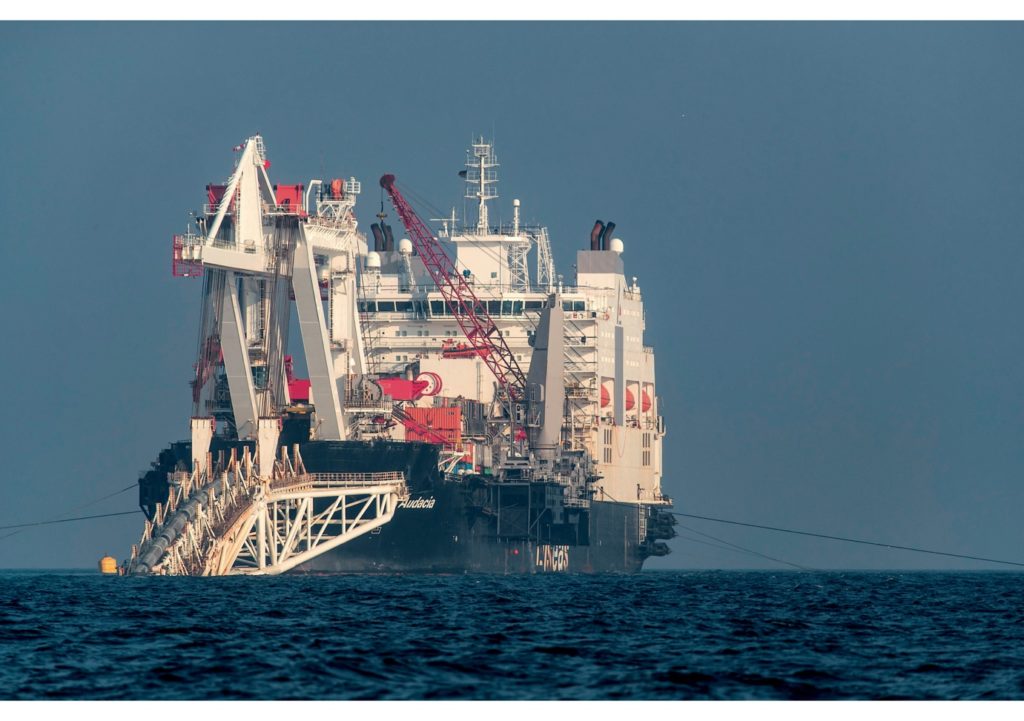

Whether or not the Nord Stream 2 gas pipe from Russia will ever be completed and brought into service, warned David McAllister, leader of Germany’s Christian Democratic group in the European Parliament, “depends definitely on the actions and the behaviour of the Kremlin.” We now know that talk of the Russians going home was optimistic; the ever-unpredictable Vladimir Putin has decided that a full-scale world war is preferable to letting Ukraine join NATO. Of course, he refers to it as “the Ukraine”, suggesting it’s really just a region of Russia. McAllister was responding at a press conference in Brussels to a question about Germany’s commitment to defending Ukraine and about German dependence on imported energy supplies. The press conference took place just before McAllister headed off to Ukraine to lead a delegation from the Parliament’s Foreign Affairs Committee and Security and Defence Sub-Committee on a fact-finding visit to the supposedly threatened country. “If the conflict with Ukraine does escalate militarily, this project from my point of view cannot move on,” said McAllister, whose views echo those of the US State Department. Europe – especially Germany – needs reliable, affordable supplies of gas, but Russia also needs the money the pipeline would generate, even though its economy looks to be sound; It has central bank reserves of almost $640-billion (€574-billion). In terms of threats and counter-threats, we appeared to be a stalemate, but such a state of affairs has seldom served to prevent conflict and Russia later bragged about how much more expensive gas would be in Europe. Many pundits thought that’s all the rhetoric was – gas.

Germany has come in for criticism for refusing – so far – to send arms to Ukraine to help with defence against a possible Russian attack. The threat, though, seemed to be more in the minds of certain Western leaders and Western media. It’s not weakness on Germany’s part, according to those who are familiar with German political history. In a field just to the east of Berlin, farmers often plough up human remains. They are all that is left of a massive and ultimately successful, if costly, Soviet advance on last-ditch Nazi defences. Putin now claims, quite falsely and with no justification, that the government of Ukraine is ‘Nazi’. It helped to end the war by defeating Hitler’s forces, albeit at a terrible cost in human lives. After starting two terrible wars that killed millions, Germany became a nation committed to peace. Following the Red Army’s arrival on German soil towards the end of the Second World War, its soldiers were encouraged to take revenge for the deaths of so many Soviet troops and for their actions in the extermination camps that the Red Army had liberated, such as Majdanek and Auschwitz.

The great Soviet General, Georgy Zhukov, had issued an order to the soldiers of the First Belorussian Front, saying: “Woe to the land of the murderers. We will get our terrible revenge for everything.” And they did. Having seen the appalling things the Nazis had done, they were happy to kill and imprison Nazi troops (often in terrible and inhumane conditions) and, most of all, to rape any German women they could find. The numbers of women said to have been violated by the triumphant Red Army have been estimated at between tens of thousands and the low millions. According to Geoffrey Roberts’ fascinating book about Zhukov, “Stalin’s General”, the Red Army troops also raped up to 100,000 women in and around Vienna, despite Austria being considered by Stalin to have been a victim of the Nazis. The Russian soldiers knew, though, that many Austrians had joined up in support of their fellow countryman, Adolf Hitler. When the Red Army “liberated” Vienna, its women suffered a similar fate to the those in Berlin.

German popular opinion, then, tends towards the pacifist these days, which is why Germany doesn’t export offensive weapons. There is widespread awareness that Germany started the First World War, in which some 37.5-million people died, and also World War Two, which killed a further estimated 68.8-million. Reticence, then, is perhaps understandable. And in any case, Putin most definitely has a point: why does NATO need to expand so far to the east? As NATO itself proclaims on its website: “The North Atlantic Alliance was founded in the aftermath of the Second World War. Its purpose was to secure peace in Europe, to promote cooperation among its members and to guard their freedom – all of this in the context of countering the threat posed at the time by the Soviet Union.” In case you hadn’t noticed, the Soviet Union no longer exists. Nobody these days would claim that “the class struggle necessarily leads to the dictatorship of the proletariat”, as Karl Marx claimed, nor would they (well, not many of them anyway) espouse the demand for a system based on the argument: “From each according to his abilities, to each according to his needs”.

It was on the stroke of midnight on New Year’s Eve 1999 that outgoing Russian president Boris Yeltsin officially handed over the reins to his successor, Vladimir Putin, who looks unlikely to hand them over to anyone else. It’s worth bearing in mind that, just as western leaders take note of popular opinion, so does Putin – normally – although he also controls the Russian media, allowing him to shape public opinion to suit his needs. His seizure of Crimea may have annoyed western politicians and western media, but it played very well in Russia, where Ukraine is still seen by many as part of Russia itself. A letter to The Economist magazine from Robert Morley, former staff member of America’s National Security Council, points out that: “Russians find it difficult to understand how NATO membership for Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania enhances the security of countries like Belgium, France and Iceland.” He has a point. Morley blames the West for facilitating Putin’s rise to unchallengeable power and his demagoguery since, as he quietly waves his fist and raises his hand in rude salute to Western leaders. Ukraine’s dislike of Putin and his rule in Russia goes back a long way: when I was last in Kyiv, more than a decade ago, on a street market, I was offered toilet rolls with a picture of Putin on the outermost sheets (the seller told me they didn’t extend all the way through) and words in Cyrillic, one of which was “Putin”, while the other was not suitable for repetition here (I had to look it up).

RUSSIA ENCOURAGED BY WEST’S FIGHTING TALK?

In any case, Ukraine’s military top brass didn’t think Russia had either the number, nor the matériel to stage a full-blown invasion, however much it might impress Russian citizens back home. They didn’t expect

Indeed, Ukraine believed that the near-hysterical talk of an imminent incursion originated in the United States and the UK, both of which are keen to divert public attention from more embarrassing reports from closer to home (vacillation and weakness in Biden’s case, blatant dishonesty and drinking parties at 10 Downing Street during a COVID lockdown for Johnson).

Also, of course, widespread public concern would help to justify NATO’s expansion eastwards. Meanwhile, Ukraine’s President Volodymyr Zelenskiy has accused Washington and the western media of stoking up panic while pointing out that there were “no tanks in the streets”, at least at that time. That hasn’t stopped the Deputy US Secretary of State Wendy Sherman from saying that the US saw every indication that Putin was going to use military force sometime between then and the middle of February. She was right.

She was speaking in late January and US President Jo Biden also stated, when asked, that “I will be moving US troops to Eastern Europe and to NATO countries in the near future.” Could that have provoked Putin’s decision to invade, or was it his long-0held fear that real democracy might spread to Russia and unseat him? Mark Milley, who chairs the Joint Chiefs of Staff at the Pentagon, told a press conference: “With 100,000 troops, you’ve got combined arms formations, ground manoeuvre, artillery, rockets, you have got air and all the other pieces that go with it, there’s a potential that they could launch on very, very little warning. That’s possible.” A less-than-cheery thought, but in case you are not yet sufficiently frightened, there’s more: “This is larger in scale and scope and the massing of forces than anything we have seen in recent memory.” Russia has refrained from tackling the West before, believing that the US had better weapons; we must assume that having weighed up human determination against matériel, he decided to go for broke.

This martial rhetoric had failed to impress French President Emmanuel Macron, who talked with Putin by telephone more than once. Macron’s spokesperson said both leaders agreed that the whole issue needs to be “de-escalated” (a popular expression that will crop up again in this narrative), although Macron also pledged France’s support for Ukraine if the worst should happen. The same is not true of Germany, which has led others to question its commitment to NATO when the chips are down. While Spain and Lithuania have sent warships to the Baltic and France has offered to send troops to Romania, Germany has seemed very hesitant, despite its offer of 5,000 military helmets (described by the Mayor of Kyiv, former boxer Vitali Klitschko, as a “joke”).

It has led to Germany’s new Chancellor, Olaf Scholz, looking weak and uncertain in the face of a real (or supposed) military threat. Those who see it that way perhaps have forgotten the way in which (and why) the German people turned against warfare after World War II. Naturally, there are plenty of people who would use this disagreement between allies as a way to weaken the EU and make Germany look feeble. In the UK, it is mainly the newspapers that campaigned for Britain to leave the EU that warned of Russian expansionism. Former US President Donald Trump, however, has claimed that “Russia controls Germany”, because of its reliance on Russian gas. He said the Russia-Ukraine crisis is “a European problem”, despite the fact that a world war would involve everybody.

You will no doubt recall, however, that Trump and Putin were reportedly good friends with one another at one time. It all gets very messy. In late January, President Biden held a video call with EU leaders, which he said went “very, very, very” well and even before it happened, Germany’s Chancellor Scholz warned that Russia would suffer “high costs” in the event of a military incursion. Scholz met with Macron in Berlin while Russia conducted military exercises close to the Ukrainian border and he warned that “a military aggression calling into question the territorial integrity of Ukraine would have consequences.” That sounds very much like a threat from Germany of armed response.

Since then, Scholz has shared a platform with France’s Macron and Polish President Andrzej Duda during which, according to the New York Times, he assessed the current situation to be “the most difficult since 1989” and issued a warning to Putin that an invasion would lead to dire consequences, “politically, economically and surely strategically.” Another warning, another sign of German determination, but according to Kremlin insiders, Macron’s claim to have made a breakthrough in talks with Putin is not true: only Biden has the power to make a deal, in Putin’s view, and that seemed unlikely.

It all looked uncomfortably like the board game “Truth or Dare”, in which players must tell an (often embarrassing) truth or face carrying out a dare put forward by another player. So here we have the contestants: Jo Biden, daring Vladimir Putin to stage an invasion of Ukraine, as he did (very successfully in Crimea), while Putin demands the truth: “are you prepared to go to war to defend a country most Americans and most Europeans, for that matter, know very little about”. I don’t know very much either, in truth, although I still have that (now very faded) toilet roll. It was the British Prime Minister of the late 1930s, Neville Chamberlain, who shamefully dismissed the Nazi invasion and takeover of Czechoslovakia, describing it as “a faraway country of which we know little.” The speech proved to be Chamberlain’s undoing and led to his replacement by Winston Churchill. Americans sometimes display a lack of knowledge of other countries, largely because their own is so huge, but Donald Trump has taken on the Chamberlain rôle in this case by accusing Washington of not knowing what’s happening in Ukraine and therefore being unable to evaluate it.

Americans sometimes display a lack of knowledge of other countries, largely because their own is so huge, but Donald Trump has taken on the Chamberlain rôle in this case by accusing Washington of not knowing what’s happening in Ukraine and therefore being unable to evaluate it.

He may have a point: Biden’s Vice-President has admitted that any sanctions imposed on Moscow can be lifted if Russia co-operates on other matters, making it a reversible threat. Not much of a threat at all, really. As far as Germany is concerned, the current US administration has always been keen to bury the Nord Stream 2 pipeline, which they fear would place Russia in a very powerful position vis-à-vis Europe, but the Germans may do it for them. As David McAllister told me, if Russia should invade Ukraine, it would mean an end to the Nord Stream 2 project with immediate effect, with or without Jo Biden, and that, indeed, is what has happened.

mean an end to the Nord Stream 2 project with immediate effect, with or without Jo Biden.

JAW-JAW IS BETTER THAN WAR-WAR

Germany, though, is more likely to fall back on a sanctions regime than to commit troops to the Ukrainian border or permit the sale of offensive weapons. German Social Democratic Party foreign policy spokesperson Nils Schmid told journalists: “We must not rule anything out when it comes to sanctions, including Swift and Nord Stream 2.” SWIFT stands for ‘The Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication, whose payments system facilitates the rapid transfer of money to complete orders and settle accounts. Germany forcing out Russia would certainly inconvenience Russian and other businesses, but the payments system is headquartered in Belgium, so it wouldn’t prove fatal to the overall system.

Schmid also warned that if the worst happened then Nord Stream 2 “will probably be unsustainable”, which was also David McAllister’s view. Germany’s Social Democrats have been openly questioning the seriousness of the invasion threat for Ukraine, with former chancellor Gerhard Schroeder warning Kyiv against “sabre-rattling”. He also argued that Russia’s military build-up is merely a reaction to NATO manoeuvres in Poland and the Baltic. The contradictory views being expressed within Germany’s coalition partnership are not helping Scholz to get across his message that Germany has, in fact, toughened its stance towards Putin.

Germany clung to its Ostpolitik thinking during the existence of a separate East German state, which Berlin refused to recognise. However, it has been noted in other European capitals that Schroeder still chairs the board of the massive Russian oil company, Rosneft. Kyiv mayor Klitschko has demanded that such influential and well-connected lobbyists should be banned from working “for the Russian regime”. The Social Democrat party’s general secretary Kevin Kuehnert has warned against ‘talking up’ international tensions as a way of getting rid of projects (like Nord Stream 2) that other parties don’t like. German Defence Minister Christine Lambrecht, also a Social Democrat, argued in early January that the pipeline’s future should not be linked to the Ukraine crisis, although she backtracked under orders from Scholz.

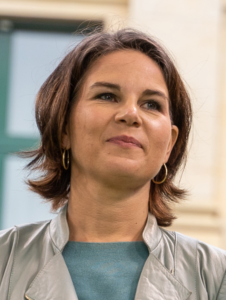

German Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock, meanwhile, has made clear that, quite apart from any qualms about exporting arms to Ukraine, Berlin is distinctly displeased by Russia’s behaviour. She pointed out that in recent weeks, more than 100,000 Russian troops with tanks and guns have gathered near Ukraine for no understandable reason, unless it is to invade (Russia says they’re on exercises). Scholz clearly has a credibility problem, although it appears to be rooted in his pacifistic tendencies against the aggressive rhetoric of those who are spoiling for a fight they wouldn’t like (and may not survive).

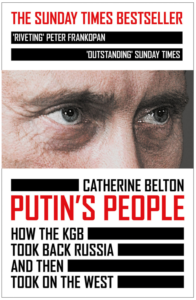

It all comes down to power. Scholz emerges as an insufficiently tough leader, at least in the eyes of his detractors, and certainly so when faced with such a seemingly warlike foe as Putin. Much of the media seems to share that view, while Putin comes across as a ruthless despot intent on broadening his power base. Putin told the Russian people that his aim was to “disarm” and “de-Nazify” Ukraine, which he accused of “genocide”, albeit without any evidence. A superb, if controversial, new book, ‘Putin’s People’ by Catherine Belton, documents Putin’s rise to power and the heavy-handed and frequently dishonest methods he has used to get there and stay there. Plenty of the people who helped him to reach the Kremlin’s presidential suite have since been side-lined, eliminated or else live in fear for their lives. Putin wants to control Russia, but more than that, some argue, he seems to want to rule the world. The book quotes Sergei Tretyakov, a former colonel in the Russian Foreign Intelligence Service (SVR), stationed in New York. In the book’s foreword, he warns Americans that today’s SVR is trying to undermine and destroy the United States with even greater determination and ability than did the KGB of old. Where is James Bond when you need him? But Putin is not trying to expand the Soviet Union: it no longer exists.

Belton alleges that it’s so that Putin can make himself richer monetarily. As he allegedly embarked on this course, he turned against the former allies who had assisted his rise. After all, some of them still had money, albeit less than before, and were privy to his secrets. The Kremlin embroiled its latest victims in legal coils with the help, it’s alleged, of expensive British law firms. It seems much remains today as it was in the days of the 19th century English writer Charles Dickens, who was not keen on engaging with the law. “Keep out of Chancery,” advises a character in Bleak House (in the UK that means the Lord Chancellor’s court, which is a division of the High Court of Justice). “It’s being ground to death in a slow mill; it’s being roasted at a slow fire; it’s being stung to death by single bees; it’s being drowned by drops; it’s going mad by grains.” Some who have been thus targeted have managed to slip out of the country in which the action was being pursued, albeit with very little of their money left, but a t least having escaped with their lives. Those thus victimised have described Putin as a ravenous monster.

MONSTROUS POWER

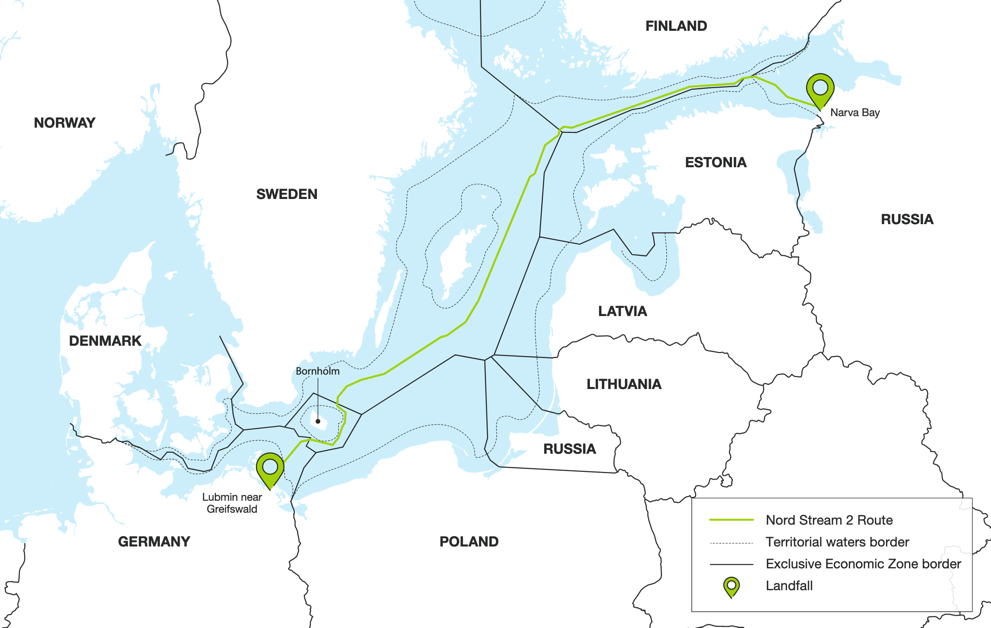

Brian Klaas writes in his fascinating book “Corruptible” that: “Not everyone who ends up in power is a great person. Right now, we have a mix. Some great people are in positions of leadership: kind coaches, bosses who empower, politicians who genuinely try to make life a bit better for others. But many, many authority figures are nothing like that. They lie and cheat and steal, serving themselves while they exploit and abuse others.” Klaas writes that they are ‘corruptible’ and do a lot of damage. Which of these two types is Putin? His former – now ex-allies – have no doubts. One thing is certain, with the threat of the war expanding, Europeans have begun to realise what the effect of Nord Stream 2 might be on the balance of power. They know, for instance, how important Russian gas is to Europe. The concern led to an unusual joint statement from Biden and European Commission President, Ursula von der Leyen. “The United States and the EU,” they said, “are working jointly towards continued, sufficient and timely supply of natural gas to the EU from diverse sources across the globe to avoid supply shocks, including those that could result from a further Russian invasion of Ukraine.” Now we shall see if it was worthwhile. So, let’s take a look at the project. The pipeline runs for around 1,224 kilometres from Ust-Luga in the Leningrad region, just south-west of St. Petersburg in Russia, to Greifswald in north-east Germany. Like the already existing Nord Stream, it has been placed under the Baltic Sea, right next to the original Nord Stream 1 and, also like it, can transport 55-billion cubic metres of gas a year, enough to supply some 26-million households. The actual construction phase was completed in September 2021. If Germany’s European partners came to rely on this supply, a threat by Russia to turn off the taps would give Moscow enormous leverage.

It’s a joint project of Russia, Germany, the Netherlands and France, but its opening had to await a decision from the EU in Brussels; we now know that answer is “no”. It’s worth bearing in mind, however, that Germany used around 53 cubic metres of Russian gas in 2017, roughly 40% of the country’s total consumption, and the new pipeline would double current capacity. The original Nord Stream 1 opened in 2011. Nord Stream 2 is based in Zug, Switzerland and is owned by Gazprom international projects LLC, a subsidiary of PJSC Gazprom, the largest supplier of natural gas in the world. It accounts for some 15% of total world gas production. Gazprom belongs to the Russian state and paid for more than half of the €9.5-billion project. The European Commission was always unhappy about it; it’s too much like putting all one’s eggs in one basket, saying in 2017 that: “it could even facilitate a single supplier to further strengthen its position in the EU gas market and be accompanied by a further concentration of supply routes.” Washington isn’t a fan, either. In November 2018, the former US ambassador to the EU, Gordon Sondland, warned that “dependence on Russian gas for Europe is geopolitically wrong”. Poland is uneasy, too.

They were right. In late January, Poland’s Secretary of State in the Foreign Ministry visited Berlin and Potsdam and expressed his country’s doubts over whether or not it could still rely on Germany and its opposition to Nord Stream 2 in the event of a Russian-Ukrainian conflict. According to the ministry, Germany should be giving a clear` “no” to the launch of the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline, “the existence of which may become a tool of blackmail on the part of Russia, as well as consent to the supply of weapons from Estonia to Ukraine.” A Polish government spokesperson, Piotr Muller, has stated that “Nord Stream 2 is not only a business project – it is mostly a geopolitical project.” Poland has no right of veto over EU certification of the project, however.

PRAYING FOR CHANGE?

Meanwhile, what about those pro-Russian rebels in Eastern Ukraine? They have been fighting their own war, ostensibly to re-unite Russia and Ukraine (or at least the part of it under their control), since 2014. Russia’s present invasion began there, as Russia absorbed the territories illegally. This war, almost forgotten by the world at large, it seems, has so far killed some 14,000 people. The rebels call their separatist enclave the Donetsk and Luhansk People’s Republics and the disagreement with Kyiv has had some very serious repercussions, such as in July 2015, when the rebels brought down Malaysian Airlines flight MH17 with a Russian-made rocket, having mistaken it for a warplane, and killing all the 298 people on board.

The separatists are often referred to in the media as “Russian-backed”, but in fact Russia had relatively little to do with them of late – until their co-operation became militarily convenient. In January, a group of members of the Duma (the Russian parliament) voted to appeal to Putin to recognise the independence of the two breakaway regions, but at the time Putin didn’t favour the idea. The eleven parliamentarians involved are headed by Gennady Zyuganov, the leader of Russia’s Communist Party.

The two regions had already declared themselves to be Russian Orthodox in religion and have banned other forms of worship or belief, jailing or fining some preachers of other faiths, as well as their followers. According to the Pakistan Christian Post, the religious rights group Forum 18 said the Luhansk People’s Republic also prevented church leaders from outside the territory from visiting their fellow believers. “Officials have barred access by the Greek Catholic bishop and a Greek Catholic priest, the bishop of the Orthodox Church of Ukraine, and many Protestant leaders,” the group claim. The rebels adopted the Russian Rouble as their currency and their schools follow the Russian curriculum, while citizens of the two supposed republics can get fast-track Russian citizenship if they wish. Moscow has issued more than 600,000 Russian passports to residents of the region since 2014. As for recognising Donetsk and Donbass as independent states, Putin feared it would serve to stoke up further the tensions over East Ukraine and the Russian troop build-up.

According to the International Crisis Group, Russia aimed to make the east’s reintegration into Ukraine less costly to the separatists and more advantageous to Moscow.

That would seem unlikely to happen, but Putin said that he wanted to avoid steps that could increase tensions, just in order to score political points. His reticence would seem to contradict the scare stories circulating in the West over his alleged intention to invade Ukraine. However, if the threat of war should recede and not in a way that’s favourable to Russia, Putin may reconsider. Meanwhile, elderly residents of the two regions who don’t support the rebels, many of them now in their 80s, will continue to suffer the depredations visited upon them by the armed separatists, including the destruction of their homes. Some residents there now effectively camp out in the shells of their wrecked houses.

It’s worth remembering during the arguments over Nord Stream 2 and Europe’s need for Russian gas that Gazprom also supply gas to Ukraine and Belarus. Mikhail Kasyanov, who began his career until Boris Yeltsin, rose to ministerial status in Russia under Putin. They fell out most seriously when he tried to reform Gazprom, now under the control of a Putin ally. Putin was using gas bills to control the two former Soviet republics, but Kasyanov proposed liberalising reforms, which he hoped would boost competition in the economy. He called a press conference to announce his plans, but just before it started, according to Catherine Belton’s book, ‘Putin’s People’, Putin telephoned him, saying: “I insist you remove this item from the agenda.” It had been at the top of that agenda, but Putin clearly saw his control over gas supplies as a potential weapon, which he was not about to surrender. It’s perhaps a point upon which the new German government may wish to ponder, although Kasyanov has also been found guilty of corruption and earned the title “Mister 2%”, for allegedly demanding a 2% cut in every deal that passed across his desk.

When the Soviet Union collapsed, according to Catherine Belton, ex-KGB people like Putin were taking much larger cuts of totally corrupt deals.

Meanwhile, Germany has seen itself as performing a vital task, keeping open communication channels with Moscow, while being virtually the only NATO member not spoiling for a fight. As the Financial Times said: “In the first crisis of the post-Merkel era, Germany is floundering.” Or playing peacemaker, if you prefer. Conciliation but with an edge seemed to be the theme of the visit to Ukraine by nine members of the European Parliament, led by German Christian Democrat David McAllister and Nathalie Loiseau of the Renew Europe group, a pro-EU, liberal-leaning party. On their first day in the country they visited the EU office for Ukraine and the security services, where they were told about various ceasefire violations and the need for strengthened security, as well as finding out what has been happening in the Sea of Azar before arriving at the Port of Mariupol, where they gave a brief press conference. McAllister assured local journalists of the delegation’s: “Solidarity with Ukraine and its citizens in this hour of uncertainty. The European Parliament clearly and unequivocally supports the independence, the sovereignty, and the territorial integrity of Ukraine.” Referring to the current crisis, he also told the media that : “The Russian military build-up at the border with Ukraine is of huge concern for all of us in Europe, because the security of Ukraine is closely linked to the security all over our continent.” Those sentiments were echoed by Nathalie Loiseau: “We are serious in diplomatic efforts to de-escalate and defuse the crisis because we know that Ukraine does not want a war, and we are serious in our firmness in case Russia would consider military aggression towards Ukraine. We stand ready to take unprecedented sanctions against Russia.” Now their words will be put to the test.

The whole affair reminds me of the British music hall song of 1878, written by G.W. Hunt and made popular by ‘The Great Macdermott’, G.H. Macdermott, a much-loved performer. The words refer to Russia’s seizure of Bulgaria and its claim upon Constantinople at that time. There is much talk in it about “the rugged Russian bear”:

We don’t want to fight but by jingo if we do…

We’ve got the ships, we’ve got the men, and got the money too!

We’ve fought the Bear before… and while we’re Britons true,

The Russians shall not have Constantinople… *

Nor Ukraine?

*

The term “jingoism”, to mean chauvinistic sabre-rattling, is thought to have originated with this popular 19th century music hall song.