The American poet Robert Frost, perhaps best remembered for his evocative poem “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening”, also wrote one called “Mending Wall”. Written in 1914, it predates both the world wars of the last century, but it contains the following few lines:

“Before I built a wall I’d ask to know What I was walling in or walling out, And to whom I was like to give offence. “

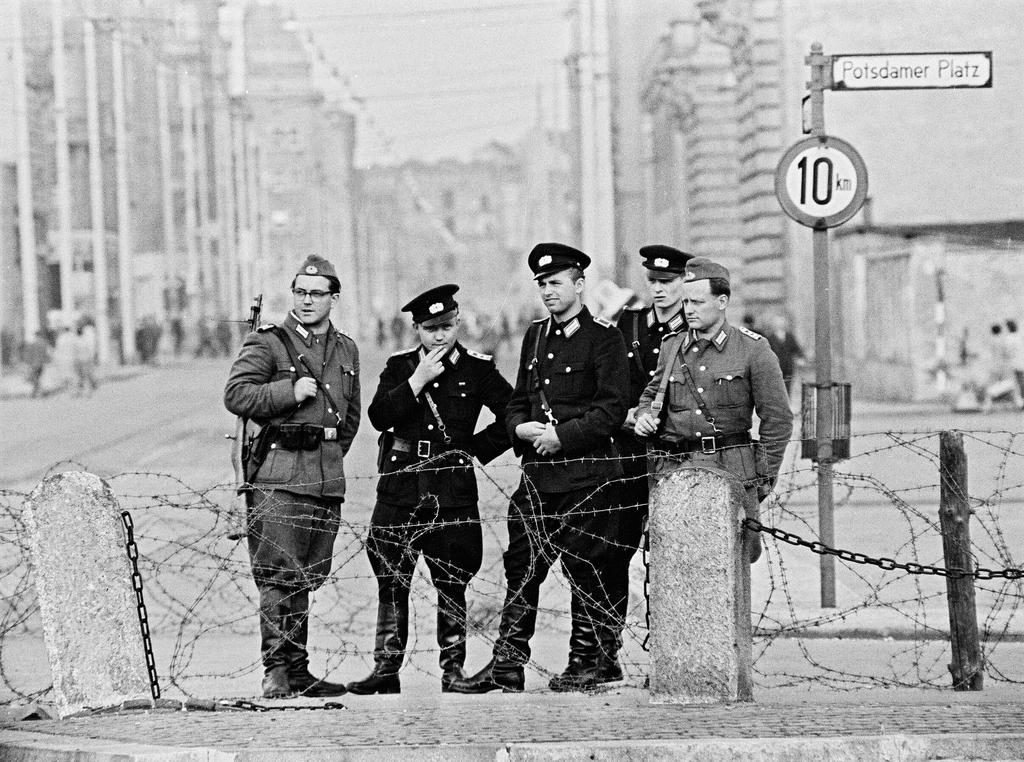

Those sentiments were not shared by the government of the German Democratic Republic (DDR, or GDR in English) when, on 13 August, 1961, they started to construct from concrete and barbed wire what they called their “Antifascistischer Schutzwall” – anti-fascist bulwark – that became known as the Berlin Wall. It divided the Communist east of Berlin from the western part, even though Berlin itself was firmly within the boundaries of the DDR, 160 kilometres from the border with West Germany. They said at the time that this was to keep Western “fascists” from entering East Berlin and “undermining the Socialist state”. In reality its main purpose was to prevent defections to the West. There were many, and a lot of East Berliners died in the attempt. Evan so, some 5,000 people successfully made it by various means during the wall’s 28-year existence; many more died trying to escape via other routes.

“The enormity of the horror is what sticks in my mind,” says Martyn Bond, a former BBC Berlin correspondent who travelled widely in the East. He knew the Berlin Wall only too well. “It was big. Very. And not just long. It was deep. There were four ‘generations’ – from simple barbed wire and bricked up windows, to round concrete pipes topping a high wall… the death strips raked to reveal footprints, the dog runs, watchtowers, automatic firing devices, vehicle traps and more.” The traps, dogs and automatic machine guns were on the DDR side, so were clearly intended to catch and kill anyone trying to reach the West, rather than to repel “fascists”. On 17 August 1962 would-be escaper Peter Fechter was shot by DDR border guards and left to bleed to death where he fell. Nobody from the West could go and help him; they knew that they would be shot if they tried.

The bizarre circumstances of life in a city divided in two were a constant presence in the life of all its inhabitants, including journalists like Bond. “I could travel around without DDR control and talk to dissidents wherever I could find them,” he said. “My risk was confusing ‘plants’ with the genuine article. They were the ones who took a risk, and what impressed me was the widespread courage – obstinacy really, being prepared to put up with everything from petty chicanery to gross mistreatment by their own ‘government’. The politics of course were a lesson in double-speak and lying through your teeth but it went all the way down society.”

THE ENEMY WITHIN?

The existence of West Berlin so far inside East Germany made the Communist powers very nervous. According to the Russian President of the time, Nikita Khrushchev, it “stuck like a bone in the Soviet throat”. The Russians tried to drive the western countries out of Berlin, despite the agreements reached at Yalta and Potsdam on sharing out the territory of conquered Germany, and in 1948 the Soviet Union imposed a blockade in a bid to starve the United States, Britain and France into leaving. Instead, the western powers instigated what became known as the Berlin Airlift, ferrying over 2-million tonnes of food, fuel and other essentials by air. Eventually, one year after introducing it the Soviets decided to end the blockade, which clearly wasn’t working. After that, a flow of refugees towards the west caused a lot of embarrassment to the Communist states. The people leaving – almost three million of them – were mostly young and skilled and a series of meetings and negotiations with Western leaders failed to resolve the issue.

Berlin was a favoured route for East Germans wanting to head west. According to the history.com website, “19,000 left the DDR via Berlin in June 1961 alone. In July, the numbers rose to 30,000 and in the first eleven days of August, 16,000 crossed the border. On the 12 August, 2,400 East Germans followed, the largest number of defectors to leave in a single day. That night, Khrushchev gave the go-ahead to the East German government to stop the flow of immigrants by permanently closing its border”. The permission was given reluctantly. The East German leader Walter Ulbricht and his regime had wanted to build a wall for more than eight years, despite having denied the intention at a press conference in June of that year, and had been secretly stockpiling barbed wire and concrete fenceposts. Khrushchev had resisted their demands, fearing it would make the Soviet Union appear brutal. He only gave way because the flood of people leaving for the West risked leaving an East Germany without essential workers and intellectuals. And so it was that on 13 August the head of the East German security forces, Erich Honecker, who later went on to become First Secretary of the East German Communist Party, ordered police and troops to erect a barbed wire fence and to begin construction of concrete barricades. The first version of the wall was put up with commendable speed, says history.com: “In just two weeks, the East German army, police force and volunteer construction workers had completed a makeshift barbed wire and concrete block wall – the Berlin Wall – that divided one side of the city from the other.” Honecker famously (and erroneously) predicted it would last a century or more. President John F. Kennedy didn’t like it but conceded that “a wall is a hell of a lot better than a war.”

Before its construction, a great many people crossed the border on a daily basis to work, do their shopping, visit friends and family or go to the theatre or the cinema. Trams and subway lines across the city made it easy. Few people took easily to the restrictions imposed by the wall, with its three crossing places: Checkpoint Alpha at Helmstedt, Checkpoint Bravo at Dreilinden and most famously Checkpoint Charlie at Friedrichstrasse in the centre of the city. On 22 October, 1961, an American official on his way to see an opera in East Berlin got into a heated argument with an East German border guard there. It led to American and Soviet tanks facing off against each other at Checkpoint Charlie for sixteen hours. History.com cites one observer who described the episode as “a nuclear-age equivalent of the Wild West showdown at the O.K. Corral”.

CROSSING BARRIERS

Even after the wall went up, there was still some carefully-controlled contact. Michael Shackleton, Special Professor in European Institutions at the University of Maastricht and Former Head of the European Parliament Information Office in the UK, was born in Berlin and spent many school holidays there with his German grandparents. “We had relations in East Germany,” he said, “and they would come to East Berlin to meet us and to collect medicines that they could not get at home. It was always a somewhat nerve-wracking experience going through the checkpoints, wondering if they would ask us what we were bringing in.” It’s not surprising, perhaps, that Berlin, especially Checkpoint Charlie, features in so many spy novels and movies. “The extraordinary contrast between East and West Berlin remains very strongly in my mind,” recalls Shackleton, “the dim lights in the East, shops with virtually nothing in the window and black-market money changers. And of course, watching armed guards on the station gantries at Friedrichstrasse as we made our way back to the West, knowing our East German relations could not follow.”

Felix Dane, Director of the Konrad Adenauer Stiftung for the UK and Ireland, recalls meeting with relatives in the DDR at a time when crossing the border with his parents and sister involved a long drive from Bonn followed by a long, tense wait at the border while everything was checked by guards. He described suddenly finding they could drive across the border easily as “surreal and joyful”. The year after it opened, his father, a diplomat, drove them through the various länder of the old DDR to see them as they had been during the long years of Socialism. “We watched the news as a family every evening and followed developments very closely,” he said. By 1992, when he did his military service, much of the euphoria had gone. “The two parts of Germany were back together,” he said, “but true unification would take much longer.” He found it “very interesting” that many of his fellow recruits were from the former DDR. “Having been on military summer camps in their youth, they knew far more than we did,” he said.

What had begun as a crude barbed-wire and cinder-block barrier, hastily-constructed and closing off the crossing points, the Wall eventually stretched to 155 kilometres in length and 4 metres in height. The Berlin section alone, dividing just the city itself, stretched for 45 kilometres, the rest of it separating West Berlin from the rest of the DDR. It was also a double wall, the two being separated by a mined and heavily-guarded area known as the “death strip”. It was under constant surveillance by guards who had orders to shoot anyone attempting to cross over to the West. Its construction cut people off from their work, their schools, their friends and their relatives. It divided not only districts and local communities but families, too. Windows of apartments and houses facing the new barrier were bricked up. By the end, the East Germans had laid more than a million landmines along the East-West border, 55,000 of them in Berlin itself. Not all the mines have been found and disarmed even now. They also employed 3,000 attack dogs, in case anyone survived the mines and the tripwire-fired machine guns.

“Bad enough by day; much more scary by night,” says Martyn Bond, recalling a visit from two senior BBC executives while he was based there. “They came to see me for a few days and we watched the last old pensioners (who were allowed out on foot over the Oberbaumbrücke but had to be back by midnight) as they hurried to get over in time. A small DDR patrol boat glided silently under the arches of the bridge and shone a searchlight on the warehouses on ‘their’ side to check nobody was chiselling their way out into the Spree. John le Carré could not have invented a more spooky scene. It certainly sobered up my visitors.” For anyone familiar with the spy novels of le Carré or even Ian Fleming, it sounds almost romantic. But it wasn’t. For those East Germans hoping for a new life in the West any thoughts of escape were tinged with terror and the very real prospect of being killed.

“The death toll was also appalling,” says Bond. “Not just at the Wall itself – bad enough at close to 200, I believe (currently estimated at 171 but the numbers are uncertain and research is continuing) but it was thousands if you add up those killed trying to cross the inner-German border, escape off the Baltic coast, or even slip out to Czechoslovakia. And those even abducted back from West Berlin after they had escaped. They had no compunction at all.” Thirty years on, it’s easy to forget; there are a great many Berliners who never knew what it was like, having been born after the Wall came down. “Now it sounds just like statistics,” says Bond. “What is left as a memorial is really just the few crosses near the Reichstag – where Peter Fechter bled to death twenty yards the wrong side of the border; even doctors from ‘our’ side would be shot at if they crossed to help.” Bond is concerned that the memory of those times will fade. “Even the museum at Checkpoint Charlie is a private initiative. There is some danger that the horror of it will be forgotten, or beautified away.”

SOWING THE WIND, REAPING THE WHIRLWIND

(Photo Berlin Wall Foundation, by J. Hohmuth)

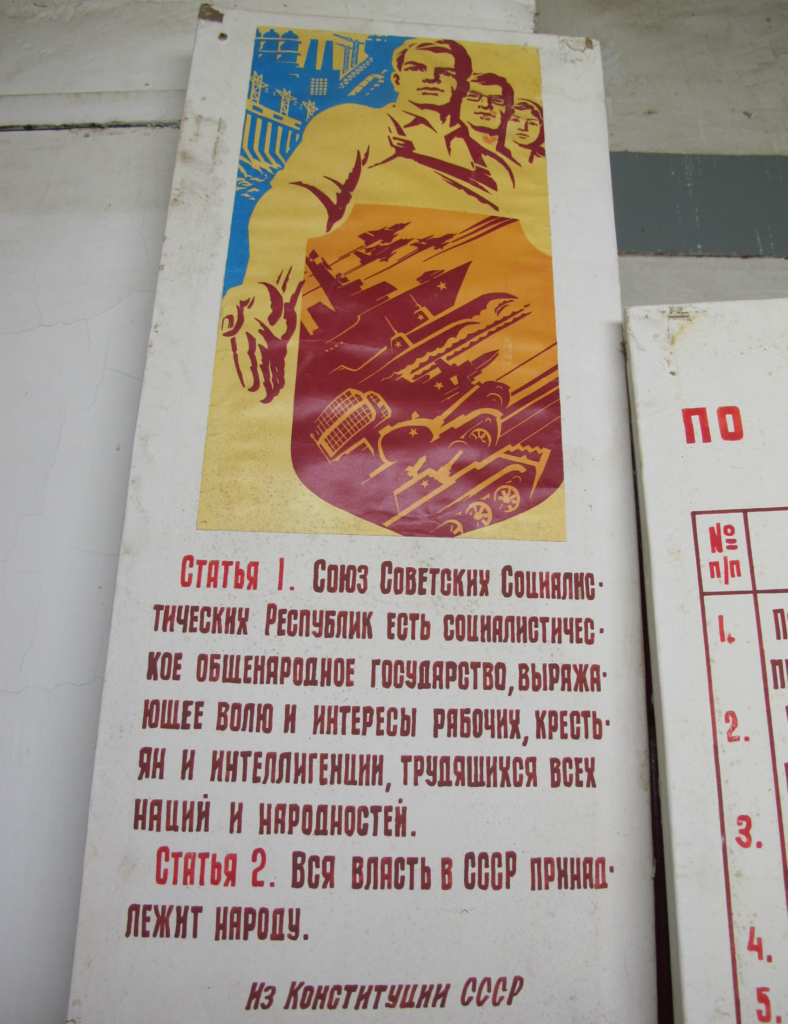

It’s easy to forget, of course, the fact that the Red Army soldiers who had “liberated” Berlin were themselves dirt-poor and had seen at first-hand what the Nazis had done, which gave them a somewhat jaundiced view of Hitler’s former capital. They had been brutalized by their experiences and were surprised by the luxurious homes (most had never seen indoor plumbing) and comfortable lifestyles they could see all around them in Berlin, very different from the picture of capitalist repression painted by Moscow.

The invasion by Germany of the Soviet Union – Operation Barbarossa – began just before dawn on 22 June, 1941. In his book “Stalin’s General”, historian Geoffrey Roberts writes: “Leading the assault across a 1,000-mile (1,600 kilometre) front were 152 German divisions, supported by 14 Finnish divisions in the north and 14 Romanian divisions in the south. Later, the 3.5-million-strong invasion force would be joined by armies from Hungary and Italy, by the Spanish Blue Division, by contingents from Croatia and Slovakia, and by volunteer units recruited from every country in Nazi-occupied Europe.” We tend to forget these days that not all Nazis were German.

Hitler had set out his goals in December, 1940: “The German Wehrmacht must be prepared to defeat Soviet Russia in one rapid campaign,” he said. The German plan was to undertake what they called “Vernichtungskreig” in Russia – a war of destruction and extermination. Again, according to Geoffrey Roberts, Hitler told his generals: “The war against Russia cannot be conducted in a knightly fashion; the struggle is one of ideologies and racial differences and will have to be conducted with unprecedented, unmerciful and unrelenting harshness.” It was. German soldiers were assured they would be exempted from punishment for any atrocities they might commit in Russia. All Communists were to be executed on the spot. By the middle of July, the Germans had penetrated some 500 or more kilometres across a broad front before the tide was turned on the outskirts of Moscow, largely through the strategies of Georgy Zhukov, arguably Stalin’s most brilliant General. “The Germans considered Slavs to be subhuman,” writes Anne Applebaum, in her book “Iron Curtain – the Crushing of Eastern Europe”, “ranked not much higher than Jews, and in the lands between Sachsenhausen and Babi Yar they thought nothing of ordering arbitrary street killings, mass public executions or the burning of whole villages in revenge for one dead Nazi.”

As they advanced into recaptured territory, Red Army soldiers saw what the retreating Germans had done – it was the Red Army that liberated Auschwitz-Birkenau and discovered the monstrous crime committed there – and they took their revenge when they conquered Berlin, mainly on its civilians. Zhukov attempted somewhat feebly to rein them in, directing his soldiers to “remain on army premises”. But Stalin’s attitude to the many, many tales of rape was less critical, according to Geoffrey Roberts, again in “Stalin’s General”. Stalin told a visiting group of Yugoslav Communists: “a man who has fought from Stalingrad to Belgrade – over thousands of kilometres of his own devastated land, across the dead bodies of his comrades and dearest ones. How can such a man react normally? And what is so awful in his having fun with a woman, after such horrors?” For the women of Berlin, then, the horrors continued, since Stalin clearly saw rape as “fun” for his troops. His attitude towards territories that later fell under Soviet control should not then surprise us perhaps.

In fact, the Nazis had made it easier for the Soviets who took over Eastern Europe. Many small and medium-sized businesses were seized and then run by Germans as the Nazis advanced, especially but not exclusively Jewish-owned businesses. Because they formed an inward-looking closed market, their trade links ended with Germany’s collapse and the Soviet Union could simply move in and take over. In any case, the German or at least Nazi-sympathising new owners had mainly been killed or else had fled, their businesses abandoned. “Most of these abandoned properties were eventually nationalised,” writes Applebaum, “if they had not already been packed up and moved, lock, stock and barrel, to the Soviet Union, which considered all ‘German’ property legitimate war reparations.” There was little opposition, even from local populations still bitter and angry with their pre-war and wartime leaders for the catastrophe that had befallen them.

NOT-SO-SPLENDID ISOLATION

So, in East Germany, the Communist party opted for isolation from the “pollution” of western ways and capitalism. Life behind the Wall went on, with workers in the East saving for years to acquire the latest Trabant while workers on the other side were able to purchase much more advanced Volkswagens or – if they were really successful – Mercedes, Audis and BMWs. It was a different world. The relative sophistication of the various vehicles tells its own story. Fashions were also important. Michael Shackleton remembers a visit to East Berlin’s Bertol Brecht theatre in 1971 with a couple of friends from Oxford who were “doing their year abroad in Germany: the attention we attracted not because of what we said or because we spoke English but because of the clothes we wore which were so unlike what everyone else was wearing was remarkable. Rather like going to a football match in a dinner jacket!” But we shouldn’t forget that there were many people living in East Germany who believed fervently in Communism and the dictatorship of the proletariat. Not everyone wanted to escape to the West, not everyone even approved of Western ideas, although most probably hoped they could earn a little more, get a nicer apartment, have better work prospects and look forward hopefully to a brighter future for their children.

(Photo Ronald Reagan presidential Library)

And so, from 1961 to 1989, the Wall stood as a symbol of division. Those who were born and brought up in the DDR know the stultifying effect of walls. German Chancellor Angela Merkel recalled her experience at a press conference during her visit to Ireland in April, 2019. She talked with the Irish people about their fears that Britain’s departure from the EU would create an unwanted border between the North and the South. She said that together they must find a solution that works for the people, not just for the politicians and businesses. “We will simply have to be able to do this. We hope for a solution. We have to be successful. Where there’s a will there’s a way.” She, of all people, knows the consequences of barriers and the delight at tearing them down. “For 34 years I lived behind the Iron Curtain so I know only too well what it means once borders vanish, once walls fall,” she said. While it stood, the western side was repeatedly decorated with graffiti, earning the soubriquet “the world’s longest art gallery”.

According to former German Chancellor Helmut Kohl, the first few bricks were taken from the Berlin Wall at Sopron, in Hungary. There, the Pan-European Picnic had been organised by Otto von Habsburg, the man who would have become Emperor of Austria Hungary if the First World War had ended differently. It attracted people from all over East Germany and even its neighbouring states, not only Hungary. As the picnic progressed, Hungarian border guards agreed to turn a blind eye as hundreds of picnickers crossed over into Austria. Having campaigned against Hitler from inside Switzerland, and then against the Communists, von Habsburg eventually became a member of the European Parliament for the centre-right European People’s Party. When I asked him in 2004 what he thought about the Wall coming down, he said: “For me of course, it is a tremendous thing because I entered the European Parliament with that goal exactly. I was the first to speak a language of Central Europe (Hungarian) here, just as a symbolic gesture. And now, to have it all true! It is a great thing.”

THE END DOESN’T MEAN IT’S OVER

It was also, in the end, an accidental thing. Because of the protests going on, leaders of the DDR decided to waive the visa rules that required citizens to give justifiable reasons for travel, such as a funeral or other major family event. They would still need visas but they should be granted more quickly and easily. However, the party official who was given the task of announcing the changes, Günter Schabowski, had been absent from most of the meeting when the decision was taken and went to the planned news conference without having been briefed. One journalist asked him when the new relaxed rules would come into effect. In fact, the decision had been to let people apply for the visas straight away with a view to issuing them a little later but instead he replied “immediately, without delay”, which launched a rush of East Berliners for the border. As the guards had not received instructions about how to deal with crowds nobody expected, it took them by surprise. After telephoning his superiors for instructions without success and in the face of increasingly angry crowds, the senior guard at the Bornholmer Street checkpoint simply opened the barrier just half an hour before midnight. Guards at other crossing points soon followed suit and the divided Berliners met, cheered, danced, drank, hugged, celebrated and put the dark days behind them, at least for a while. The nightmare wasn’t quite over but they were starting to wake up at last.

Celebrating the event, though, is not easy for many Germans. Tearing down physical walls doesn’t in itself unite the people on either side and there is hostility among many in what was East Germany over continued high levels of unemployment and relative poverty there. It has fuelled support for the far-right Alternative für Deutschland party, with its populist promises. I can understand why they feel resentment,” says Felix Dane, “first changing from the Ostmark to the Euro, and now facing more change through technology, migration and climate change. They feel left behind.” Ironically, apartments near the vanished Wall on the eastern side in Berlin now command very high prices because they didn’t suffer the “modernisation” inflicted during the 1960s and 70s on properties in the West. Original features are valuable and, in the old West Berlin, rare. What’s more, the date the Wall fell, or at least gave rise to what was described as “the world’s biggest street party” is the same date the Nazis commemorated Kristallnacht, the notorious attack on Jewish businesses, homes and synagogues conducted by Nazi paramilitaries throughout the lands they controlled in 1938. For that reason alone, 9 November is not a date that’s easy for Germans to celebrate, even now. In addition, they recall that the deaths along the Wall were the result of Germans killing Germans, not a comfortable memory.

Brendan Donnelly, Director of the Federal Trust and a former pro-European Conservative MEP, recalls the policy of Ostpolitik, instigated by then Chancellor Willy Brandt to reach out to the citizens of the DDR and keep them informed about real events their own media wouldn’t mention. “I was at the British Embassy in Bonn in the 1970s working on Berlin questions,” he says. “I became more and more convinced that the Ostpolitik was not only morally right but also effective in hollowing out from within the rotten East German state. I used to read Neues Deutschland every day and the contrast between its tired clichés and the Western reporting to which GDR citizens had access through the Ostpolitik was overwhelming.” He thinks the seeds of East Berlin’s destruction as a separate state were sown then. “No regime could ever survive for long such a daily challenge to the lies on which it was constructed from a richer, more numerous, more developed neighbour. I certainly did not foresee the end of the USSR but I never believed the GDR could survive for very long.” Even so, Felix Dane says the final reunification came with a mix of joy and disbelief, because after the fall of the Berlin Wall, unification still had its opponents. The then British Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher was not in favour and was not alone in having doubts while there were disagreements about exchanging Ostmarks for Deutsche Marks on a one for one basis, against the advice of the Bundesbank. The decision was political, not economic, and seriously damaged the economy of the old DDR.

CRUMBLING HEROES

(Photo Jim Gibbons)

In 2011, while working with Deutsche Welle TV, I travelled to Berlin where we filmed a current affairs programme, European Journal, in the deserted Russian enclave of Wünsdorf, about 40 kilometres outside of the city itself, from which any war with the West would have been conducted. It had been the Red Army’s headquarters in Germany and home to some 75,000 men, women and children. It was a sizeable housing complex and a well-supplied barracks, known to Germans living nearby at the time as “Little Moscow”. There was the large concrete bunker that had been the Soviet air force’s air traffic control centre. Back then, it had been packed with computers, screens and many kilometres of cabling. Now it is just a slightly damp old building, crumbling slowly into the ground beside the “village” in which Russian forces had lived. They were not forbidden to interact with ordinary Germans living nearby but contact was limited and, in many ways, unnecessary. The Russians had their own theatre, cinema and shops (goods were cheaper there than in German shops), now covered in graffiti with damp peeling stucco and missing plaster. The nearby flats, built for Russians, were being slowly made habitable once more while we were there, so that they could provide homes for locals. And there were locals. We had a rather lugubrious guide who had worked as a fixer back when the settlement was still busy with Russian military personnel.

Among the other sites, he took us to the railway station, long disused, whose line ran straight to Moscow. It had been, he told us, a daily service, which took two days to complete. The train didn’t stop along the way. Weeds sprouted from the platform and all along the trackside were young silver birch trees. He pointed them out nostalgically as “proper birch trees,” grown from seeds the train picked up as it ran through Russia. The officers’ “club” at the Russian enclave was the building in which had been lodged the German athletes training for the 1936 Olympics. The building looked a little sad and run-down, but then so did the large but somewhat more recent statue of Lenin outside, a testament to its later occupants. Now they deteriorate together.

It doesn’t take long for the seemingly immutable present to become the forgotten or misremembered past. All those words of propaganda, uttered to praise one political philosophy and disdain another. It goes on all the time. It still goes on today in the United States, Britain, Poland, Hungary, everywhere. The only memorial to the wall is the small private museum near Checkpoint Charlie, the Mauermuseum (Wall Museum), which was created one year after the Wall went up. It exhibits things connected with it, both tragic and heroic, including objects used in escapes, like the modified Isetta bubble car in which one successful escape was made. And, of course, escapes and attempts at escape went on, despite the terrible risks. Martin Bond remembers: “A high point. Attending the West Berlin premiere of the Balloon escape film and meeting the families who got away by sailing over the obstacle at 2,500 meters. Winning was what mattered, my job was to broadcast back to the DDR when we had a good story like that.” Tiny parts of the Berlin Wall have been turned into fridge magnets (I have one on my fridge) and whole sections of the wall have been exported as symbols of the fight for human rights and against tyranny. Two adjacent sections stand outside the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg, a memorial to what can happen when those in power consider human rights unimportant.

Those pressing for new walls, or taking decisions that make more walls inevitable, would be well advised to look at Berlin. A bustling city today – one of my personal favourite cities in the world – but still haunted by the memories of thirty and more years ago. “Full unification will take two to three generations,” Dane believes, “It can’t be done in ten years.”

There is an old saying that good fences make good neighbours, but they don’t when they divide people from their families, friends and the places in which they grew up and went to school, or from a better future for their kids. They merely help to ensure that the affection and friendship that preceded the construction are never quite as close or amicable afterwards. President Reagan, in his 1987 speech in Berlin, said “Tear down this wall”, but today’s would-be wall-builders should note the underlying message: it would have been far better if it had never been built.

Jim Gibbons