Picture : President Barack Obama signing of documents for a nuclear arms treaty with Russia in 2011©White House Photo by Chuck Kennedy)

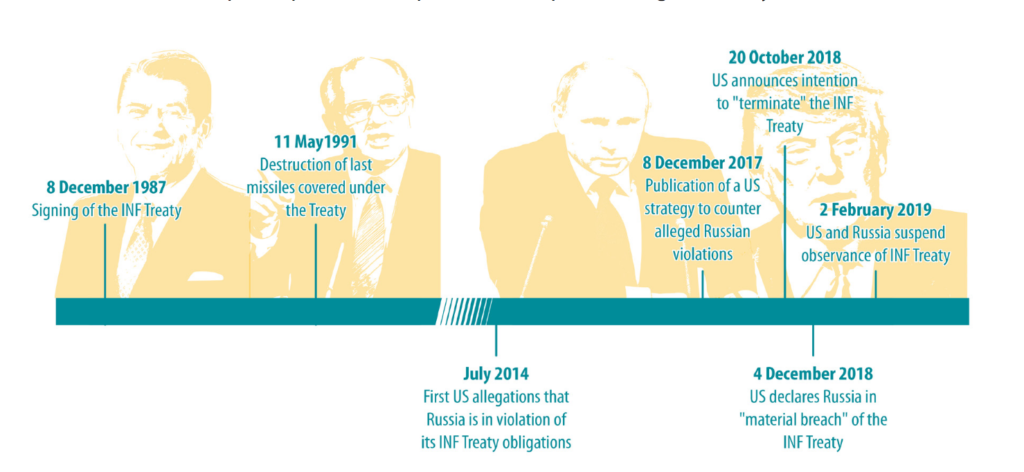

“We can only hope that this history-making agreement will not be an end in itself but the beginning of a working relationship that will enable us to tackle other issues, urgent issues,” said President Ronald Reagan at the signing in the White House of the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty, normally referred to as the INF Treaty. Hopes were high around the world on that remarkable day, 8 December, 1987. Mikhail Gorbachev, then General Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (the Soviet leader, in fact), who was about to add his signature alongside Reagan’s, said “What we are going to do, the signing of the first ever agreement eliminating nuclear weapons, has a universal significance for mankind, both from the standpoint of world politics and from the standpoint of humanism.” But that was back in the supposedly bad old days of a polarised world with mutually-assured destruction keeping aggressive, twitchy fingers away from the launch button. “We can be proud of planting this sapling,” said Gorbachev, “which may one day grow into a mighty tree of peace.” He also quoted the 19th century American philosopher and poet Ralph Waldo Emerson, who said “The reward of a thing well done is to have done it.” That was long before Presidents Trump and Putin turned up, wielding George Washington-style axes to Gorbachev’s sapling.

The world has moved on. Officially, the Cold War may be over but there are dangerously aggressive attitudes around the globe. NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg said it was Russia that breached the terms that Gorbachev’s and Reagan’s teams had spent seven years discussing by developing the 9M-729 missile. Russia denies that it breaks the terms of the treaty and accuses America in turn of causing a breach by placing a missile defence shield in Europe and by developing weapons to be carried on drones. That may be so but it’s hard to see how the 9M-729 (also known within NATO as the SSC-8) could be seen as complying with the terms of the INF Treaty. The Treaty expressly required both signatories to eliminate ground-launched ballistic and cruise missiles with a range of between 500 and 5,500 kilometres. That agreement resulted in the destruction of some 2,692 short- and intermediate-range missiles, 1,846 of them Soviet and 846 American, and forbade either side from developing more. Russia’s 9M-729 is a highly-mobile ground launched cruise-type missile, capable of carrying nuclear warheads and with a range of – guess what – 500 to 5,500 kilometres. NATO Secretary General Jan Stoltenberg has said that: “By fielding multiple battalions of SSC-8 missiles, Russia has made the world a more dangerous place.”

The whole idea of the INF Treaty was to keep Europe safe. Both nuclear powers retained their long-range and battlefield weapons but European capitals were no longer easy to target. The longer-range weapons can be tracked more easily. Not long after the Treaty was signed in 1987, for instance, Britain abandoned its “four-minute warning” alert system, believing its chances of being hit at short notice had diminished, even though the Treaty did not affect the United Kingdom’s own nuclear arsenal. It did mean, though, that the highly controversial deployment of American nuclear-armed missiles at RAF Greenham Common and RAF Molesworth, both of which drew huge protests, could come to an end.

Geopolitical realities have moved a long way from the Gorbachev-Reagan era. Back then, at the signing ceremony, Reagan quoted an old Russian saying: “trust but verify”. Verification very much underpinned the INF Treaty, allowing each side to have inspection teams in each other’s territory. However, the verification mechanism ended in 2001, leaving America with no way of examining the new missile, which it labelled a “missile of concern”.

When reports surfaced of Russia’s breach, the NATO allies sought dialogue with Moscow. The NATO-Russia Council met in January 2019, but Russia continued to deny that their new missile breached the Treaty, and refused to respond to questions or to take steps to restore a verifiable compliance, which would presumably have included the destruction of its new weapon. Moscow claimed it had a range of less than 500 kilometres but a statement by America’s Director of National Intelligence in November 2018 claimed that Russia had test-flown the missile over much greater distances from a fixed launcher. The 9M-729 has clearly been in development for at least a decade, although Russia was keeping its existence under wraps until western anger at the annexation of Crimea made Putin bare his claws.

NEVER A FAN

President Vladimir Putin, despite denying Russia’s breach of the Treaty, had been opposed to it for a long time. According to Jens Stoltenberg, Secretary-General of NATO, Putin first expressed his desire for Russia to quit the Treaty at the Munich Security Conference in 2007. Putin’s apparent dislike of the Treaty does not appear to be widely shared; Russia’s Deputy Foreign Minister, Sergei Ryabkov had previously warned that withdrawing from the treaty would be a dangerous step and could lead to a renewal of the arms race. He told the RIA Novosti news agency that if the US withdrew “we will have no choice but to undertake retaliatory measures, including involving military technology”. Of course, with the 9M-729 Russia is already a decade ahead anyway. Probably. Basically, Moscow is saying “you can’t prove our missile breaches the Treaty but if you try to match it we’ll build a bigger one”. It comes from the “yah-boo-shucks” school of playground argument.

According to the Center for Strategic and International Studies’ “Missile Threat” report, the 9M-729 missile, developed by the Russian arms manufacturer NPO Novator, is probably based on the Russian Navy’s 3M-54 Kalibr missile (known in NATO parlance as the SS-N-27 Sizzler), although it could also be a modified version of the Iskander-K or Kh-101. Flight testing began in 2008 and the first test firing was in July 2014, and then again in September, 2015. US experts say it did not fly further than the 500-kilometre INF limit on those occasions, which allows Putin to claim compliance. The US Air Force National Air and Space Intelligence Center (NASIC) estimates its maximum range at 2,500 kilometres. The missile is six to eight metres long, is road-mobile, easy to hide and can carry a 450 kg warhead. It has a guidance system developed by the Russian defence company GosNIPP and could shorten warning times to just a few minutes.

In February 2017, US officials claimed that Russia had deployed two 9M-729 battalions, one at its Kapustin Yar test range in south-west Russia, the second at an unknown operational base. Each battalion has four launchers and each launcher is equipped with six missiles. In January 2019, Russia publicly displayed the missile for the first time. Russia’s Chief of the Military Missile and Artillery forces claimed that despite a more powerful warhead and an improved guidance system, it does not have a range that would breach the INF Treaty. As far as is known, by December 2018 Russia had produced fewer than a hundred 9M-729 missiles, but it is a weapon that would fit comfortably into Moscow’s favoured strategy of dividing the NATO allies through perceived threats and thus winning what they call a “short-of-war” (meaning the avoidance of actual fighting through bullying) or, at worst, a “short war”. NATO’s defence of Europe relies on getting so-called “follow-on” forces to the battlefield or potential battlefield quickly, but the 9M-729 could easily target ports, airfields and marshalling points to make that deployment far more difficult. Without the INF Treaty, the Alliance must seek new solutions. NATO must be able to convince Russia that a quick blitzkrieg-type victory, even if initially successful, would face strong opposition that could turn it back. NATO’s Enhanced Forward Presence in Poland and the Baltic States is aimed at demonstrating to Moscow that an attack on any NATO state is an attack on all of them and will meet with a massive response. The plan is to persuade Russia that not even a surprise attack would achieve its objectives. They may take some persuading.

A NEW WORLD ORDER?

On 2 August, 2019, US President Donald Trump announced America’s withdrawal from the INF Treaty, citing Russia’s breach through its development of the 9M-729 missile. In a statement, US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo said “Russia is solely responsible for the treaty’s demise.” Trump also expressed concern over China’s intermediate-range missile arsenal as a reason for withdrawal, which is slightly odd since China was never a party to the INF Treaty in the first place. It is, however, a matter of concern for NATO, a point highlighted by its Secretary General at the High Level Conference on Arms Control and Disarmament in October, 2019. “A new supersonic cruise missile. And an assortment of new drones and anti-ship missiles. This shows the world how far China has come,” Stoltenberg told delegates, “but let me underline: China is not violating any arms control treaty. But as a major military power, it has major responsibilities. And it is time for China to participate in arms control.” The rising might of a more globalist China is a concern in the West and President Trump said he has spoken to Beijing as well as to Moscow about a new nuclear arms treaty. He told reporters they were both “very, very excited” at the idea. Given that it took Reagan and Gorbachev seven years to negotiate the INF, no-one should anticipate early results, especially since the United States tested a ground-launched cruise missile that would have breached the INF Treaty just days after withdrawing from it, something that unsurprisingly drew instant criticism and accusations of hypocrisy from the Russians.

The INF Treaty was especially important for Europe. It came at a time when there was a lot of fear over the deployment of Soviet SS20 missiles, even though the decision to site American missiles on European soil was controversial and led to protests. But it also led, eventually, to Reagan and Gorbachev signing the INF Treaty. Putin’s Russia, though, is not like Gorbachev’s. NATO has seen Russia violating the INF Treaty for years, whilst ignoring repeated calls to return to compliance. And that’s not all. “Russia’s negative record on arms control goes beyond the INF Treaty,” said Stoltenberg, “it suspended its participation in the Conventional Forces in Europe Treaty back in 2007, a treaty with which all NATO allies continue to comply. Russia also has a record of circumventing the OSCE Vienna Document, which provides for inspections of military activities and exercises, and reduces risk of unintentional conflict. In fact, Russia has never opened an exercise for mandatory OSCE Vienna Document observation.”

And Russia is not the only concern. More global players are developing advanced missile systems and nuclear weapons. “North Korea and Iran for example are blatantly ignoring or breaking the global rules. And spreading dangerous missile technology around the world,” warns Stoltenberg. Meanwhile, China already has hundreds of its own missiles with ranges that would have been banned under the INF Treaty, had it applied to China. What’s more, it recently put on show a new advanced intercontinental nuclear missile capable of reaching the United States. In addition, China boasts a new supersonic cruise missile and an assortment of new drones and anti-ship missiles. It is not, of course, violating any arms limitation treaties: it hasn’t signed any. But NATO believes that as a major world military power, China has responsibilities and should participate in arms control. Trump may believe Beijing is “very, very interested” in the idea but as yet there’s little evidence. Indeed, the Chinese Foreign Ministry has said that “China will in no way agree to making the INF Treaty multilateral”. And for sensible reasons: China has fewer nuclear warheads and missiles than either Russia or the United States, so a treaty that guaranteed parity would mean increasing China’s nuclear arsenal, not reducing it. China would never agree to a treaty that set in stone America’s and Russia’s nuclear supremacy.

HIGH-TECH WORRIES

The problem is that the worries go beyond nuclear weapons; technology has moved on. Stoltenberg reminded the Arms Control and Disarmament conference that there are now new threats, such as cyber-attacks; hypersonic glide vehicles, which are launched from a rocket and then glide to their target at hypersonic speeds, not necessarily following a predictable ballistic path; autonomous weapon platforms that can kill and destroy without human participation; artificial intelligence and biological weapons. It’s been claimed that America is working on using modified insects as vectors to genetically alter standing crops, theoretically to help them to cope with drought or pest attack, but which could be weaponised. Existing international treaties do not seem to fully constrain these sorts of experiments.

Given the limited range of options, NATO is determined to support the Nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty (NPT) as the only viable way towards what it hopes may be a world free of nuclear weapons (presumably without believing it’s really achievable). NATO’s commitment to the NPT will be re-emphasized at the Review Conference in April 2020. Although both America and Russia have now withdrawn from the INF Treaty, it did achieve remarkable results. “The INF treaty eliminated a whole category of weapons capable of carrying nuclear warheads,” says Stoltenberg. “As a direct consequence, almost 3,000 missiles were destroyed. When the first START Treaty (Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty, signed by United States and the USSR in 1991) entered into force in 1994, the US and Russia were limited to 6,000 strategic offensive arms each. Now, under New START, they are limited to no more than 1,550 each. These treaties have worked.” 1,550 each is still a lot of missiles.

Russia has called for a moratorium on the deployment of nuclear-armed cruise missiles in Europe, but as ideas go it’s a non-starter: Russia has already deployed such weapons, in violation of the INF Treaty. But that doesn’t mean there’s no room for dialogue. The difficulty comes with finding ways to be reassured about the other side’s intentions. As Reagan said at the signing of the INF Treaty, quoting that old Russian saying: “trust but verify”. And Russia has not been keen on letting people check up on its activities since the INF verification process ended. Even so, NATO says it is keeping the door open to dialogue, and at the same time hoping to expand nuclear weapons limiting negotiations to other players. NATO also wants to see the OSCE’s Vienna Document brought up to date to reflect the new geopolitical realities. With fifty-seven member states in Europe, North America and Asia the OSCE (Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe) is the world’s largest regional security organisation, dating back to the early 1970s when it was set up to foster dialogue between the West and the Soviet Union. The Vienna Document requires participating states to provide each other with information about their military forces, including manpower, budgets and major conventional weapons systems, on an annual basis. They are also supposed to warn each other about up-coming military activities and exercises and to accept three inspections of their military sites each year. In addition they are supposed to invite observers to view their activities, something Russia has found ways of avoiding. Stoltenberg remains hopeful that procedures to tighten verification measures can be agreed and that this will reduce risks. It all rather depends on the OSCE members agreeing to it.

ONE-SIDED CONVERSATIONS

As far as Russia is concerned, the signs are not encouraging. NATO suspended practical cooperation with Russia in 2014 in response to Russia’s annexation of Crimea. Russia has shown itself willing to use force against neighbouring countries, and Russian forces are present not only in Ukraine but also in Georgia and Moldova against the wishes of the relevant governments. Many Moldovan people I spoke to in the capital, Chișinău, a few years ago, have applied for Romanian passports – they share a common language and are ethnically Romanian – because Romania is a member of the European Union. EU membership is generally seen as a useful safeguard in a dangerous world, especially with a hostile power firmly established in Transnistria, the breakaway province on the border with Ukraine that still tries to live in a version of the old Soviet Union. A thousand Russian troops are stationed there, to the consternation not only of Chișinău but of neighbouring Kyiv, too. Meanwhile, pro-Putin propaganda is pumped endlessly into the country, greatly annoying those who prefer to see a future in Europe. The propaganda comes as no surprise to NATO, because it fits with Russia’s pattern of behaviour, which includes cyber-attacks, disinformation campaigns and attempts to interfere with democratic processes, quite apart from its failure to be transparent about its military exercises.

Despite the fact that the INF Treaty was principally about the security of Europe, the reaction to the Treaty’s demise has been surprisingly muted. European leaders seem reluctant to accept that the threat from nuclear weapons is back on the agenda. Some mild regrets were expressed about the decisions to withdraw but there were no anguished pleadings to the Americans to reconsider, nor to develop and deploy a missile to match the 9M-729. The lack of panic among Europe’s leaders may seem surprising. Perhaps they don’t view Putin’s expansionist Russia as being quite such an adversary as the Soviet Union used to be? Of course, Poland and the Baltic states are very well aware of just how dangerous Putin is. Other European countries are also well aware of how Putin uses the threat of Russia’s nuclear capability to intimidate them and to try to drive a wedge between them. Maybe they have just grown too used to the relative protection the INF provided; today’s schoolchildren don’t see television warnings about how to react to the threat of a nuclear attack. I still remember vividly how the Cuban missile crisis dominated conversation at my school in 1962, and how much talk there was in the newspapers and on television of the possibility of a nuclear war. After the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, there were also growing fears about some possible future presidents, known to be militaristic. In the American 1960s political comedy show, That Was The Week That Was, the satirical songwriter Tom Lehrer performed (among many others) a song about the spread of nuclear weapons, called “Who’s Next?”. In it, Lehrer expressed concern about the then Governor of California, the fiercely anti-Soviet Ronald Reagan, who was not even considered a likely candidate by many. “I’ll try and stay serene and calm when Ronald Reagan gets the bomb,” he sang (on the subsequent recording it was changed to “when Alabama gets the bomb”). Reagan signing the INF Treaty must have come as a surprise.

HEADS IN THE SAND

The European Council for Foreign Relations (ECFR) has mused that today’s European leaders are more confident than their predecessors were that America would come to their aid in the event of invasion. The fear that America might not was what led to the deployment of “weapons of deterrence” in Europe back then. It was felt that the deployment would discourage the Soviets from gambling that the President of the United States would, at a pinch, decide not to “risk Chicago for Berlin”. Do today’s Europeans have confidence that Trump would run such a risk for them? As the ECFR puts it, “And pigs might fly”. The reality may be rather more worrying. “The sad truth is that European indifference to the death of the INF Treaty stems not from confidence but from a deep-seated reluctance to accept that nuclear issues are back on the agenda at all,” says the ECFR commentary. “As ECFR found in a comprehensive recent survey of attitudes towards nuclear deterrence across Europe, Europeans are choosing to address these issues with, in the words of the report’s title, ‘eyes tight shut’.”

The “comprehensive survey” to which the article refers is mildly alarming. Among its conclusions, it says: “Firstly, despite the growing insecurity all around them, Europeans remain unwilling to face up to the renewed relevance that nuclear deterrence ought to have in their strategic thinking. Secondly, and as a consequence, national attitudes remain much where they were when the subject dropped off the agenda at the end of the cold war – which is to say, scattered across the entire spectrum from those who continue to see nuclear deterrence as an essential underpinning of European security to enduring advocates of unilateral nuclear disarmament.” Perhaps it lends weight, ironically, to something Karl Marx wrote: “Hegel says somewhere that all great events and personalities in world history reappear in one fashion or another. He forgot to add: the first time as tragedy, the second as farce.” But there’s nothing farcical or remotely amusing for Europeans about Russia’s newfound confidence and insouciant adventurism. In the opinion of the ECFR, this is no time to be turning a blind eye to Putin and his ambitions: “Europeans need to take their heads out from under the duvet and start thinking seriously about how to create a ‘Euro-deterrent’ – that is, about how to effectively extend the deterrence capacity of the French and British nuclear arsenals to cover European partners and allies. No one pretends that such a goal will be quick or easy to achieve. But, without it, all talk of European ‘strategic autonomy’, or of a Europe able to exercise any real degree of strategic sovereignty in the twenty-first century, is ultimately vacuous.”

Nobody in Europe seems to be engaging in serious discussion as to how best to counter Russian aggression. Even anti-nuclear Germany is wondering what should happen next. “I firmly believe that we must manage once again today to agree to rules on disarmament and arms control in order to prevent a new nuclear arms race,” said German Foreign Minister Heiko Maas. “The end of this treaty raises the risks of instability in Europe and erodes the international arms control system,” France’s Ministry for Europe and Foreign Affairs said in a statement. “France reaffirms its commitment to arms control and to real and verifiable nuclear disarmament anchored in legal authority, and encourages Russia and the United States to extend the New START Treaty on their nuclear stockpiles beyond 2021 and to negotiate a successor to that treaty.” China’s Foreign Ministry spokesperson, Hua Chunying, meanwhile (and to nobody’s surprise) put all the blame on Washington. “Withdrawing from the INF Treaty is another negative move of the U.S. that ignores its international commitment and pursues unilateralism. Its real intention is to make the treaty no longer binding on itself so that it can unilaterally seek military and strategic edge.” No mention of those Russian 9M-729 missiles, then.

WHERE NEXT?

The website Foreign Policy.com makes an interesting observation. It asks why the INF Treaty went wrong, citing the United States concern over the 9M-729 missile (although that was developed in the mid-2000s and was known to exceed the permitted range) while Russia, unsurprisingly had its own complaints and allegations, especially the Aegis Ashore facility in Romania which Moscow argued could be used to launch land-attack missiles in violation of the Treaty. “Mutual blame is to be expected when arms control treaties come crashing down,” says the website, “but as per usual, there are deeper forces at work. The interesting question is not ‘who was breaking the rules?’ but ‘why did they prefer to see the treaty collapse rather than fix it?’” It’s an interesting question that raises an issue few are talking about: the shift in geopolitical power. “Despite Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and its military build-up in the Black Sea and the Baltic,” the website argues, “the biggest challenge of international politics is posed not by revanchist Russia but by rising China. When the INF Treaty was negotiated, China was a minnow in a world dominated by two sharks. Indeed, its military was so dilapidated that it had recently lost a war with neighboring Vietnam.” Russia, says the website, is now a second-tier power in China’s eyes.

Although China’s arsenal may look small compared with Russia or the United States, it is at the forefront of technology, with its own hypersonic missiles capable of far exceeding the speed of sound and thereby striking in minutes. The kinds of missiles limited by the INF Treaty may have been state-of-the-art back in the days of Gorbachev and Reagan and they could certainly kill many, many people, but they’re old hat now. The challenges that we now face have become greater as a result of the end of the Treaty and are no longer only confined to Europe. Whatever negotiating may be done in future – assuming any fully-armed power wants to make the effort – must also involve new powers, such as North Korea, Iran, Israel, India and Pakistan, not to mention Britain and France. Nobody wants to concede anything as the world lurches from crisis to crisis. Countries need closer alliances, yet alliances are breaking up. Any sort of ban on nuclear weapons looks increasingly unlikely, for much the same reason that a number of teenagers in rough inner-city estates carry knives: they know a knife makes it more likely that they will be attacked or killed but they feel safer with a weapon to hand, even if it confers little or no real advantage. It’s why there are so many needless knife crimes over minor disagreements and what they call “respect”.

Gorbachev is still alive, although now in his eighties. He is deeply concerned about the collapse of the INF Treaty. In an interview with the BBC recently, he said: “As long as weapons of mass destruction exist, primarily nuclear weapons, the danger is colossal. All nations should declare – all nations – that nuclear weapons must be destroyed. This is to save our lives and our planet.” He is afraid that things have deteriorated a lot since he and Reagan signed the INF Treaty. Asked how he would describe today’s complex present-day manifestation of the Cold War, he replied: “Chilly, but still a war. Look at what’s happening. In different places there are skirmishes, there is shooting, aircraft and ships are being sent here, there and everywhere. This is not the kind of situation we want.” Were he still alive, it’s highly probable that Reagan would agree with that analysis. However, it’s far less likely that Trump, Putin or, for that matter, Xi Jinping would. In Putin’s case, it’s all about Russian honour. In his speech at the signing of the INF Treaty, Gorbachev quoted Ralph Waldo Emerson, of ‘build a better mousetrap’ fame. Perhaps I could add a different quote by him now: “The louder he talked of his honour, the faster we counted our spoons”.

Jim Gibbons