Featured image copyright: A military parade at the main square of the capital of Transnistria © gospm.ru

Officially, it doesn’t really exist in the normal sense, yet half a million people live there. In documents, it calls itself the ‘Pridnestrovian Moldavian Republic’ (or ‘PMR’), but most people know it as Transnistria, a 400-kilometre-long but narrow remnant of the Soviet Union wedged between Moldova and Ukraine. Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov Lenin and Josef Stalin could stroll there unconcerned, surrounded by statues of themselves and hammer-and-sickle flags flying in the breeze, the only such place in the world. It’s as if the intervening years never happened. And yet Transnistria’s young people seem happy and somehow less concerned about how best to seek success and how to get their hands on the latest mobile phone than their western counterparts. Street crime is relatively rare, but large-scale corruption is not. It wasn’t always so tranquil. Between 1990 and 1992, Transnistrian troops fought a bloody battle for separation from the newly independent state of Moldova. It was Russia that brokered a ceasefire and remains a ‘guarantor’ of peaceful co-existence, which means it has stationed troops there which are proving very difficult to get rid of. Geographically, Transnistria is still part of Moldova, although sited on the other side of the Dniester river, hence the name. It is even recognised as part of Moldova by the European Union, some of whose goods are available there.

The issue of Transnistria arose when the Soviet Union collapsed and its mainly Russian-speaking inhabitants refused to become part of Moldova, at least in the political sense. The current situation seems unlikely to change any time soon, despite Moldova’s newly-elected President, Maia Sandu, calling for Russian troops to leave.

In a press conference, Sandu pointed out that Moldova had never been a party to any agreement for Russian troops to be stationed there . She reminded the media that Moldova had for a long time insisted that the troops should be replaced by civilian monitors under the Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE). The idea of withdrawal was dismissed as “irresponsible” by Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov in December 2020, which hardly came as a surprise. He may have had ulterior motives, after all: when Russia unilaterally annexed Crimea, Transnistria asked to become part of Russia, too. So far, it remains “the invisible state”. Sandu won the Moldovan presidency despite Moscow’s open backing for her rival and sitting president, Igor Dodon, with the declared aim of balancing relations with East and West.

If I have given the impression that everything in Transnistria is hunky-dory, although locked in the Soviet past, that would be wrong. The territory is still subject to the “restrictive measures” imposed by the European Union. Under the restrictions, “member states of the EU shall take necessary measures to prevent the entry into, or transit through, their territories of persons responsible for obstructing the political settlement of the Transnistrian conflict, and campaigns of intimidation and closure of schools using the Latin script in the breakaway territory.” The restrictions were again extended in 2020 to the following year.

The Transnistrian authorities labelled the latest extension “inappropriate” and said: “This is an unfortunate misunderstanding and we call on the Council of the European Union to abandon the fixed approach that hampers the consolidation of constructive practices in the process of regulating Moldovan-Transnistrian relations and undermines the authority of the EU as an observer in the 5+2 consultative format.” Most of the people I have met and spoken to in Moldova have expressed very little sympathy with the breakaway region and quite a lot of fear of Russia.

That’s why many of them have taken advantage of Romania’s offer to obtain a Romanian passport, making them de facto EU citizens. They were genuinely, openly fearful of a Russian invasion and takeover.

The Council of the European Union first imposed travel restrictions on members of the Transnistrian leadership in February 2003. The European Court of Human Rights, in a number of cases, most notably Catan and Others v. Republic of Moldova and Russia, has ruled that the language policy of the breakaway territory, which forbids the use of the Latin alphabet in schools, violates the right to education. Article 14 of the European Convention provides that: “The enjoyment of the rights and freedoms set forth in [the] Convention shall be secured without discrimination on any ground such as sex, race, colour, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, association with a national minority, property, birth or other status.” The applicants in this case complained that they had been discriminated against on grounds of their ethnicity and language. Requiring Moldovans to study in an “artificial language” (they presumably mean Transnistrian-accented Russian), unrecognised outside Transnistria, caused them educational, private and family life disadvantages not experienced by the members of the other main communities in Transnistria, namely Russians and Ukrainians. The Court ruled in the applicants’ favour by 16 votes to 1, rejecting an objection from the Russian judge and awarded them more than €6,000 each in compensation, which Russia refused to pay.

FROZEN CONFLICTS

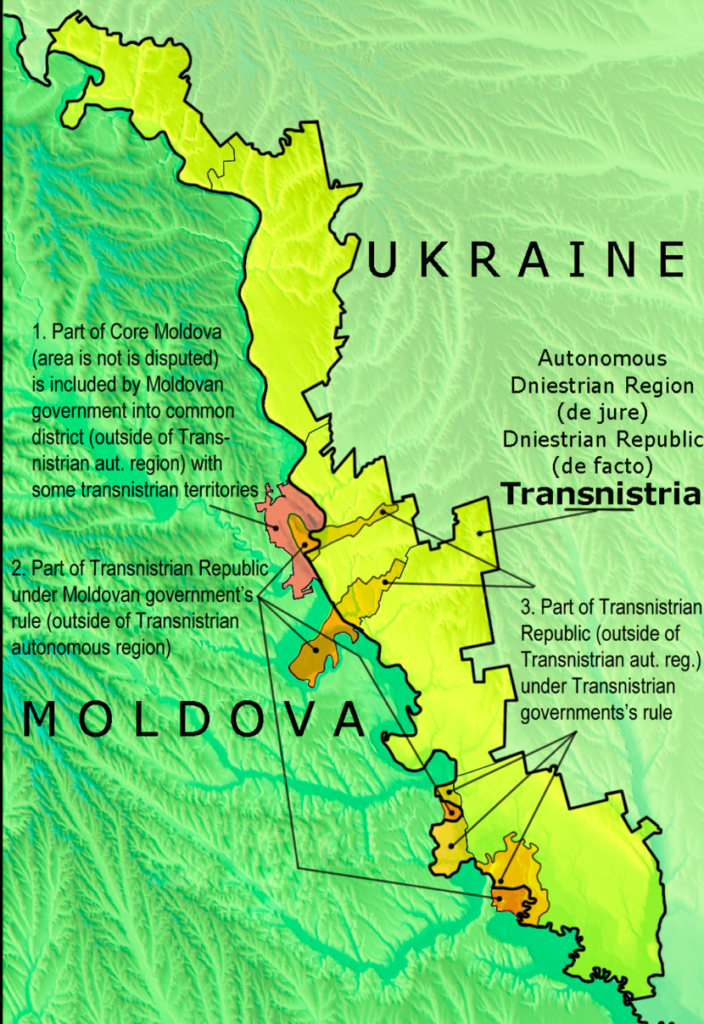

Political map of Transnistria with the differences between the Autonomous Dniestrian Territory de jure and the Pridnestrovian Moldavian Republic de facto © Wikipedia

Transnistria had since 1924, together with a number of other territories which are now part of Ukraine, been part of the Moldavian Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic. The population of Transnistria was originally composed principally of Ukrainians and Moldovans/Romanians, but from the 1920s onwards it was subject to significant immigration by industrial workers from elsewhere in the Soviet Union, particularly Russians and Ukrainians. In a census organised by the Soviet Union in 1989, the population of Transnistria was assessed at 679,000, composed ethnically and linguistically of 40% Moldovan, 28% Ukrainian, 24% Russian and 8% others. Politically, though, most seem to identify as followers of Moscow rather than the Moldovan capital, Chișinău. The Council of Europe is still actively engaged in what are called “confidence building measures” (CBMs) in the fields of human and social rights, media, education, civil society, children’s rights, the rights of people with disabilities, cultural heritage, health within prisons and drug control. Where prison health is concerned, the issue is mainly about the treatment of prisoners suffering from infectious diseases.

The Council also wants prison staff and inmates to be made more aware of how to prevent, control and care for such illnesses as TB, HIV and Hepatitis. It also seeks closer cooperation between Chișinău and Tiraspol (the capital of Transnistria) in the field of deinstitutionalisation of children with disabilities. In addition, the Council wants to see greater respect for human rights “in line with the standards of the European Social Charter and other international instruments”. So basically life is OK in Transnistria, as long as your horizons don’t stretch further than Russia.

No United Nations member recognises the independence of Transnistria, which it declared in 1990. The only ‘countries’ that do (although they’re not ‘real’ countries) are Abkhazia (an area of the South Caucasus that most other countries see as part of Georgia), the Republic of Artsakh (more commonly known as the Nagorno-Karabakh Republic and really part of Armenia, which considers it a breakaway territory) and South Ossetia (another self-declared state that is geographically part of Georgia), all of which are struggling for recognition themselves. These are in a state of what is called “frozen conflict”: the bullets aren’t flying but there’s no love lost between the opposing sides. Thus we have one unreal state only recognised by three others; the break-up of the Soviet Union did leave an almighty mess. However, it seems that Transnistria is viewed in Moscow as a model for how to handle Ukraine’s recalcitrant region around Donbass.

The President of Ukraine, Volodymir Zelensky, was only a teenager when Russian troops entered the region in the early 1990s ‘to keep the peace’. They’re still there, of course. That’s why Zelensky is, he says, “very cautious” about deploying his own peacekeeping forces to police the ceasefire in the Donbass area, where Ukrainian troops are still facing pro-Russian separatists. “I am cautious,” he said at a press conference in Kyiv, “because I do not want a scenario similar to Abkhazia or Transnistria to be applied in Donbass.” It seems, however, that Moscow sees Transnistria as a model for other rebel regions like Donbass: areas with limited independence, backed with Russian military might and looking to Russia for leadership and support.

Could this be the favoured forerunner for frozen conflicts in what Russia sees as its post-Soviet ‘sphere of influence’? We must remember, however, that despite having troops stationed there, not even Russia recognises Transnistria as an independent country. Transnistrians can obtain Transnistrian passports but they are only valid in Abkhazia, the Republic of Artsakh and South Ossetia, which is somewhat limiting. There are no flights in or out of Transnistria, either.

If you are interested in the folklore of Transnistria, try looking up “Transnistria fairy stories” on-line. What you get are articles about the Transnistrian currency: the Transnistrian ruble, which is not convertible into any other currency. It’s a bit of a message, really, although one of the coins does feature the famous firebird. The firebird is part of a popular Russian folk tale, in which a huntsman ends up seeking the bird on behalf of a heartless tsar. He finds it in the end, marries the magic princess (naturally) and the wicked tsar ends up dying, in this case in a cauldron of boiling water.

Cheery tales for little ones! It’s a popular emblem on Transnistrian coinage, it seems, (the bird, not the boiled tsar) although I cannot find any reason to link the story with Transnistria. Having once been part of Moldova, which had itself once been a part of Romania, perhaps we should take note of some Romanian folk tales, of which there are many, mainly miserable. For example there is one about the childless royal pair promised a child as long as it could be granted eternal youth (something we would all like to have, after all). When the young prince reaches the age of 15 he is sent off to seek the gift he was promised. Instead, he finds a happy kingdom with a beautiful princess, whom he marries, of course. However, he gets homesick and on returning finds that thousands of years have passed, his parents’ palace is now a ruin and, in a dusty cellar there, he finds an old chest in which, he discovers, lies the bony, rotting figure of Death, who reaches out and turns him to dust.

That must have helped many a Romanian child to sleep more soundly. “Goodnight, sleep tight, beware of magic kingdoms in your dreams and avoid Death”. Incidentally, on entering Transnistria you will find booths very willing to change your euros, dollars or anything (except Moldovan lei) into rubles, but they’ll be far less keen to change them back. Transnistria needs foreign currency.

How did Transnistria come to exist, if it can truly be said to do so? Reggie Kramer, a Research Intern with the Eurasia Program at the Foreign Policy Institute explains it rather well: “During the 19th century, present-day Moldova was part of the Russian Empire, which the Ottoman Empire had ceded to Russia. Following the Russian Revolution of 1917, the Moldovan Parliament quickly formed and, in 1918, voted to join the Kingdom of Romania. The newly-formed Soviet Union (USSR) did not recognize Romania’s political control of what it considered Russian territory. In 1924, the USSR created the Moldavian Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic out of the territory that it still controlled: the land east of the Dniester, modern Transnistria. During and after the Second World War, the USSR regained control of all of present-day Moldova; it maintained control over this area until 1990. That was when the trouble started and a disagreement over nationality erupted into a civil war. It mainly affected the leaders and the military; many citizens claim they were fairly indifferent as to the final outcome.

HOLIDAYS IN THE 1980s AND EARLIER

But if Transnistrian currency is listed under “folk stories and fairy tales”, can you actually visit Transnistria? It is, apparently, the least visited part of what is the least visited country in Europe, Moldova, but if you’re feeling adventurous and want something unusual, you can certainly go there. The Young Pioneers website says that “the Russian-backed rebel republic offers a whole host of opportunities for the most adventurous travellers.” Tempted? The website continues: “A part of the brotherhood of breakaway nations, it is one of the few places in the world to see the embassies of Caucasus breakaway states South Ossetia and Abkhazia. From a vast amount of Communist relics and a Soviet way of life, there is arguably nowhere else like Transnistria on earth.” Yes, I really think that’s probably true. It goes on to list other not-to-be-missed items on the tourist trail. “Join us,” it urges, “in the last stronghold of the USSR, the land of bullet riddled Lenin statues and abandoned Soviet nuclear bunkers.” I must admit, I actually find the idea quite appealing, in an odd sort of way, although I can understand why many would not find it quite so irresistible.

As for accommodation, Tiraspol offers one allegedly overpriced luxury hotel (Transnistria needs foreign currency, so don’t be surprised) and, as an alternative, “the classic Soviet relic, Aist, which is not for the faint hearted but is also an experience you will never forget.” Having stayed in run-down Soviet-era hotels in the past, none of which I shall identify here, I can agree that they are, in the main, unforgettable, however much you may try. (I recall one where the balcony doors from the bedroom, which would have led onto a balcony that apparently not been swept or cleaned for years, were sealed with peeling sticky tape through whose several gaps an icy draught blew (it was December). The carpets throughout turned up in the corners to reveal dirty floors and were in other places pockmarked with old cigarette burns. Naturally, there were large, noisy Russian refrigerators in which to store one’s vodka in a bedroom whose pillows reeked of stale cigarette smoke. It provided very good coffee, though, which I certainly didn’t find in Kyrgystan.) For your Transnistria holiday there is a fascinating day-by-day itinerary proposed, which includes a visit to see “one of the largest Lenins in the world and a perfectly intact giant Soviet Emblem”.

That would be something to show the folks back home! The trip includes a visit to a Soviet nuclear bunker with thirteen underground floors and – arguably more appealing – a convenience store where you can buy what used to be the Soviet Union leadership’s favourite brandy (they call it Cognac, which must annoy the French) for just $3 (€2.45) a bottle. In one place, it even mentions “hidden wineries”. I didn’t know that Transnistria produced wine but it seems that it does, hidden or not.

The website Dark Tourism warns, however, that Transnistria is, compared with what most of us are used to, a fairly lawless and potentially dangerous place. “Crucially, one has to avoid getting into any sort of trouble while in the PMR,” it warns, “also given that you’re pretty much out of reach of embassy or consular help there. (Embassies based in Moldova are de facto unable to exert any influence on Transnistrian territory, and as it’s a non-recognized state there are naturally no consular representations of other countries within the PMR.) So tread carefully. If you do go, though, the exoticness of the place can be very rewarding indeed for the traveller with a taste for such things.” EU citizens can enter without a full registration process, as long as their stay is shorter than ten hours, which Dark Tourism regards as quite long enough to see most things of interest. You will still have to complete a form in duplicate, keeping one half to give back on your departure. Border guards may hassle you a bit, it’s said, mainly in the hope of a bribe. Wine is said to be of good quality and very cheap. The wine may prove to be Moldovan, but where brandy is concerned, Transnistria produces the best.

It has also produced a problem that simply won’t go away. The OSCE is still trying to settle the differences between Tiraspol and Chișinău. “The OSCE Mission to Moldova facilitates a comprehensive and lasting political settlement of the Transdniestrian conflict in all its aspects, strengthening the independence, sovereignty and territorial integrity of the Republic of Moldova within its internationally recognized borders with a special status for Transdniestria.” I should point out that “Transdniestria” is an acceptable alternative spelling for Transnistria. There’s still a lot to do to normalize things: until 2018, vehicles bearing Transnistrian licence plates were not allowed to enter EU countries. From that year on, vehicle owners were allowed to go to specially designated offices and change their Transnistrian plates for special Moldovan plates that comply with the Vienna Convention. Qualification documents from universities in Transnistria can now also be recognised by EU higher education facilities once they have been “apostilled” by the Moldovan Ministry of Justice, again thanks to the OSCE.

The problems in Transnistria are not, despite claims in some quarters, an ethnic conflict between Transnistrians and Moldova. In 1989, Moldovans made up around 65% of the population, with Ukrainians next at 14% and Russians not far behind with 13%. Even today, Moldovans remain a minority, albeit the largest minority, with around 40%. As before, Ukrainians are next with 28%, just ahead of Russians at 26%. However, they communicate with each other in Russian, so Moldova’s language law of 1989, effectively outlawing Russian in favour of Romanian, is partly to blame for what happened next. Russian speakers did not favour the use of the Latin alphabet, nor did they want compulsory language proficiency in Moldovan Romanian to be enforced, even if it did permit the “local use” of Russian. Apart from language, there was an ideological split, too. Moldova’s stated economic and political aims clashed with deep-seated Soviet ideology and would have disadvantaged local leaders in Transnistria. Most of the Moldovan industry was built in Transnistria and it was therefore more profitable for its leaders to attempt secession in order to retain full control of their economic assets. The Marshall Center has this explanation of how the conflict started: “In June 1990 the Supreme Soviet of Moldova adopted a declaration on sovereignty. In September, the reaction of Transnistrians was to proclaim the Dniester Moldovan Autonomous Republic (RMN). The Supreme Soviet declared this act void and null, but could not enforce this on the ground.” And so Transnistria declared independence. No-one has found a solution satisfactory to both sides in some thirty years, so prospects for early resolution are not good. Or to put it another way, перспективы скорейшего разрешения не очень хороши. Transnistrian residents had been promised “a little Switzerland” and they believed it because before its secession, it was the most prosperous region of the Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic, an industrial powerhouse that supplied the rest of the territory with electricity and generated around 40% of Moldova’s total GDP. It’s not much like Switzerland now.

Education remains a major issue. Eight of Transnistria’s schools still answer to the Moldovan Ministry of Education in Chișinău and they continue to educate in Romanian, using the Latin alphabet. The Transnistrian government has been trying to take them over ever since the year 2000. In 2004, Transnistrian police surrounded the schools and it was left to the OSCE to provide emergency food supplies for the students. Later, the parents, teachers and schoolchildren appealed to the European Court of Human Rights, arguing that their right to education had been violated.

The court agreed and ordered Russia, which had supported the clamp-down, to pay compensation. That, however, did not bring the matter to a close, with the teachers regularly called in for questioning by the Transnistrian Ministry of State Security (still referred to as the KGB) even today. Before term starts, head teachers are warned not to fly Moldovan flags and police attend in an attempt to ensure the school follows the self-proclaimed state’s laws. The intimidation, backed by Russia, seems to be working, with the number of children in Romanian language schools falling from 6,000 in 2004 to just 1,600 or fewer. One father, who drives 50 kilometres to get his daughter to a Romanian language school has been detained by police three times, according to Deutsche Welle. In 2004, the EU added a number of Transnistrians who were involved in provoking the “school crisis” on its visa-ban list of Transnistrian representatives responsible for the deadlock in trying to settle the conflict. According to Balkan Insight, “Free access to education in the Romanian language was one of the conditions in the recent ‘Berlin Plus’ package negotiated in 2017 and 2018 by Chișinău and Tiraspol under the OSCE‘s patronage.

Over the past six years, the number of pupils studying at Romanian-language schools in the breakaway region has diminished by 35 per cent as a result of Transnistria’s policies.”

GUNS GALORE

Russia deploys around 1,500 troops in Transnistria, mainly to guard the World War II era weapons dump, and Moldova’s new president, along with many of her fellow Moldovans, thinks it’s time for them to go. “Russia says that the Operational Group of Russian Forces (OGRF) guards ammunition depots here,” Sandu told the Russian RBC news website, “but there are no bilateral agreements on the OGRF and on the weapons depots.” Clearly, Sandu would like to be remembered as the president who brought Transnistria back into the Moldovan fold, perhaps on a federal basis, and the OGRF’s arms are the most convincing argument for getting rid of the Russian forces, even if it falls well short of convincing Moscow. “These weapons depots are a big problem for us. It’s dangerous,” she said in her sit-down interview with RBC. “These weapons need to be removed and the OGRF needs to be withdrawn.”

In a press conference in mid-December 2020 Putin told the BBC’s Moscow correspondent, Steve Rosenberg, that East-West tensions are the fault of NATO expanding eastwards, despite promising not to. Russia, under his leadership, was, he said, “white and fluffy” by comparison, freeing countries to go their own way after Soviet rule. Would the people of Eastern Ukraine and especially the Tartars of Crimea share that view, I wonder?

Vadim Krasnoselsky

Putin also dismissed Russian involvement in the attempted poisoning of opposition politician Alexei Navalny (whom he referred to as “our blogger”), demanding sight of the evidence that Novichoc was used. He told journalists that if he had ordered Navalny’s death he would, indeed, be dead, and dismissed claims of scientific proof as “western propaganda”. If Russia is true to Putin’s word, why not withdraw its troops from Transnistria and replace them with unarmed OSCE monitors, even Russian ones? In what way, exactly, would that be ‘irresponsible’, as Lavrov has claimed? Russia’s world view is clearly very different from the West’s. In any case, the presence of large quantities of weapons and ammunition provides Russia with an excellent excuse for staying where they are, “just to guard them”. Incidentally, the border between Transnistria and Moldova is patrolled and policed by Russian soldiers.

The London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) has even mused in an LSE Online article in 2016 that Transnistria could turn out to be ‘the next Crimea’. It seems an extreme idea but in an unstable region not entirely without credibility. “The Russian government has vocally protested against measures such as the fortification of the Transnistrian-Ukrainian border by the new Ukrainian authorities and Ukraine’s ban on Russian servicemen stationed in Transnistria from transiting Ukrainian territory, but has shown no inclination to either recognise or annex Transnistria, instead calling for a ‘special status’ for the region within Moldova and even reducing its financial support for the separatist regime.” Transnistria was, prior to 1940, an autonomous region of Ukraine, when the Soviet Union combined it with Bessarabia to form the Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic. Back then, the idea that Moldova might become a fully independent country and that the USSR would cease to exist never entered into anyone’s calculations. As Balkan Insight reports, “Russia sees its control of the strip as a useful bargaining chip with Moldova and Ukraine and has made no real effort to persuade its client regime in Tiraspol to reunite with Moldova. The first ‘frozen’ conflict in the region set a pattern for similar armed conflicts in Georgia in 2008 and eastern Ukraine after 2013.”

For those now living in Transnistria, life is not without its day-to-day problems, some of which have been highlighted by the Council of Europe, as it reported following a visit in 2015 by the Conference of International NGOs. “Some NGOs based in Chișinău conduct activities in that self-proclaimed republic (Transnistria), the independence of which has not been recognised by any state to date. Several cases already ruled on by, or pending before, the European Court of Human Rights demonstrate that violations of human rights in the region are frequent and states’ efforts to implement relevant judgments are very limited. INGOs have protested about illegal arrests of human rights defenders, harassment of NGOs and cases of torture in the region.” But, as always, it is the unpredictable ambitions of Putin’s Russia that cause the most alarm. He has supported Abkhazia and South Ossetia, which makes Russia a real threat to Georgia. “Further cementing ties, Russia signed the Treaty of Alliance and Integration with South Ossetia in 2015,” reports the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. “There were similar concerns in Moldova, where Russia’s military presence in the breakaway Transnistria region is seen as a potential lever the Kremlin could use to destabilize the rest of the country. Russian support also facilitated the victory of the pro-Russia Igor Dodon in Moldova’s 2016 presidential election. He has since emerged as a leading EU-skeptic and advocate of closer ties with Russia.” But he has now been replaced in the presidency by Maia Sandu, of course, a far more pro-EU figure who has promised to redress the balance Dodon had tilted towards Moscow. No wonder the Kremlin favoured her opponent.

Putin has his Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU), which is his response to the EU and which he took under his control in 2012. He persuaded (bullied, in fact) Belarus and Kazakhstan to sign up to the EAEU and although Armenia initially declined, it nevertheless provided the pressure to stop Yerevan from signing a previously agreed Association Agreement with the EU. It later caved in and signed up to the EAEU along with Kyrgystan. Moldova has signed an Association Agreement with the EU and even Uzbekistan, Central Asia’s most populous state, continues to resist Russian pressure to join, remaining instead an EAEU “observer.” Russia and Kazakhstan, Eurasia’s two economic heavyweights, have derived some economic benefits from preferential trade agreements. But the much poorer members, such as Armenia, Belarus, and Kyrgyzstan, have less to show for it. Moscow offered discounted energy prices, access to labour markets, and other economic enticements to join the EAEU, but the benefits have often been lost to corruption, however, which has made the public doubt the advantages of EAEU membership. The EAEU is also often wracked with disagreements among members over trade and regulatory regimes, which Russia inevitably often seeks to exploit. The more heavy-handed Russia becomes as it attempts to get closer integration, the more other members resist and drag their feet. As the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace puts it, “while the EAEU has become an established actor in the region, it is far from a happy union.” Perhaps Putin is learning what the EU learned long ago: if you bully people into submission or descend to using coercion you end up with a union that simply isn’t sufficiently unified to work. Transnistria is too small, perhaps, to matter much in the great scheme of things except as a constant irritant to Moldova and a reminder that Russian troops are never far from Chișinău. Sandu may find that, like many of life’s irritants, they’re very hard to get rid of, even if they offer precious little advantage to Putin. Troops on the doorstep doesn’t look very “white and fluffy”, whatever he says.