© china-railway.com

“The man who moves a mountain begins by carrying away small stones” wrote Confucius in his Analects. Confucius – more correctly Kong Fuzi, which means Master Kong but whose name was Latinised as Confucius – wrote down quite a few sayings, many of them somewhat ambiguous to a Western mind. He was, according to John Keay in his enthralling book, China – a History, “a poorly paid minor official in the irrelevant state of his birth”. The 4th century BCE Chinese philosopher Zhuanzi, a central figure in the philosophy of Daoism whose proper name was Zhuang Zhou, described Confucius as having “brambles for brains”, which is hardly flattering. Confucius had a very limited circle of disciples to mourn him when he died in 479 BCE but no-one has been more influential for Chinese thought, not even, I think, Mao Zedong or Karl Marx (and yes, of course I know he wasn’t Chinese). Mao will be all but forgotten in two or three hundred years from now in all probability, but Kong Fuzi will still be being quoted, his precepts followed and his sometimes-puzzling analects studied. I think that would be more than he expected or felt worthy of. He was a civil servant to his core and believed in obedience to his masters.

Much of his philosophy is concerned with honour and respect. Apart from being a civil servant, he was also a scholar of some note. He believed, somewhat naively, it seems, that morality and virtue would triumph if only men would study. If only! Since his death, two-and-a-half millenia ago, many have studied his writings but there’s been little agreement on how best to translate them, even if the gist of his argument is straightforward. Respect is the key. “Sons must honour their fathers,” Keay explains him as having said, “wives their husbands, younger brothers their elder brothers, subjects their rulers. ‘Gentlemen’ should be loyal, truthful, careful in speech and above all ‘humane’ in the sense of treating others as they would expect to be treated themselves.” Not a bad idea, although most if not all of today’s political leaders seem to ignore that. Coming back to the present day and China still sees itself as the leading power in Asia and therefore as meriting the unquestioning respect of neighbours, almost to the point of a kowtow (or khàu-thâu), in which the subservient party must touch the ground with his or her forehead when confronted by someone of higher rank. Enter into a deal with China’s President, Xi Jinping, and that is, figuratively speaking, what he will expect in return. No-one must ever question Beijing’s motives or actions, nor criticise what it does (and for Beijing, read Xi Jinping). Indeed, if your country is in a trade deal with China it might be best for your trade minister to carry around a cloth to protect his forehead from the dirty ground. Because China is a bully to countries it sees as smaller and less important than it is, which is certainly how it regards its nearest neighbours and, indeed, most of the other countries in the world. Perhaps we should note part of another of Confucius’s analects: “Is it not gentlemanly not to take offence when others fail to appreciate your abilities.” Try telling that to Xi.

Just look at some of the ‘punishments’ China has dished out in recent times. China has blocked the import of lobsters from Australia, along with other commodities, such as coal, barley, timber and copper ore. The Chinese people may have an unsatisfied demand for lobsters (they eat a lot, it seems, or used to) while Australian lobster fishermen are stuck with crustaceans they can’t sell, all because of a number of infringements, such as condemning China’s treatment of the Uighur people, or criticising its activities in Hong Kong and of allegedly having a media that is ‘biased’ against Beijing (for which read that it is actually reporting China’s many abuses, rather than ignoring them as Beijing would prefer). Other countries to have been metaphorically ‘sent to Coventry’ by Xi include Sweden for daring to criticise the kidnapping and jailing of a Swedish citizen born in China, Gui Minhai, who published books Beijing didn’t like; Norway because its Nobel Committee awarded a prize to the Dalai Lama; South Korea for permitting the deployment of anti-missile batteries against North Korea that Beijing thought could peer into China, and so on.

The list of complaints is long and it’s clear that China thinks the reasons for their actions should be clearly understood and in any case immediately acted upon, whether they are understood or not. China even ordered a boycott of the South Korea-owned department store chain, Lotte, which has branches in China, because it had provided the land upon which the missiles were to be sited. China is like the prickly old granny every family fears, because she can get into a huff about anything or nothing. Anyway, Australia’s Prime Minister, Scott Morrison, has stated publicly that he won’t cave in to Chinese bullying and that he intends to take China to the WTO over its barley ban. That will scare them!

ALL ABOARD!

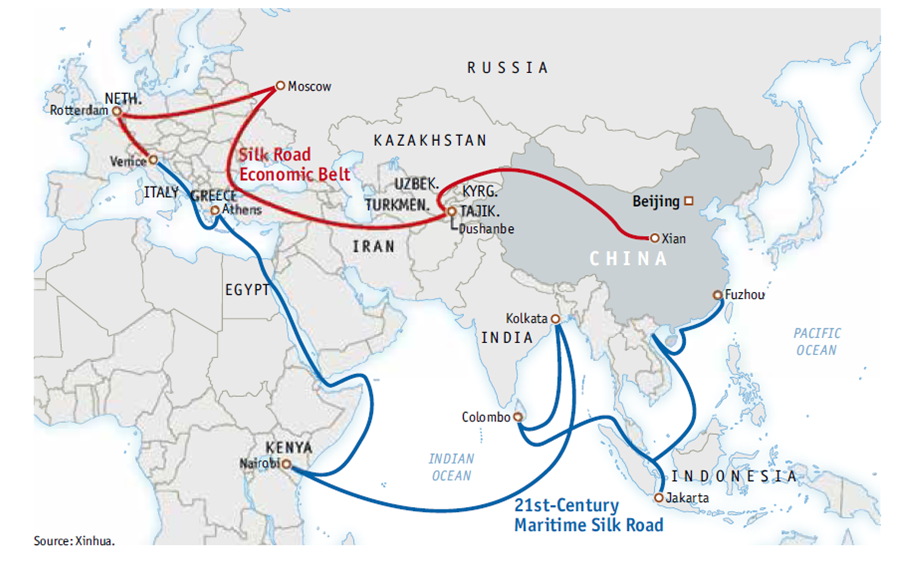

Meanwhile, China’s famous One-Belt-One-Road (OBOR) project continues. Its aim, supposedly, is to restore the ancient Silk Road, linking China with Europe. But before anyone starts talking romantically about Genghis Kahn, Tamerlane, Marco Polo or the fabled delights of Samarkand, you must empty your mind of silkworms, camels and the long list of emperors, good, bad and forgettable.

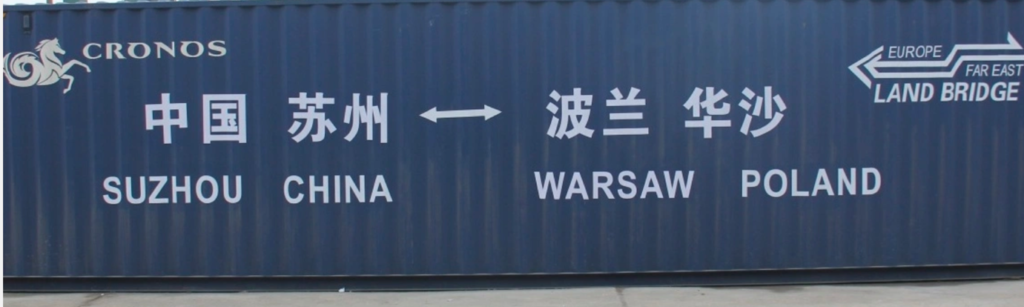

Today’s silk road will be a creation geared more towards conquest, albeit commercial rather than military. OBOR (also known as BRI, the Belt and Road Initiative) is a long-term strategy which encourages investment in Eurasian transport and logistics such as railways to transport freight, and encourage economic integration. China likes to plan far ahead. China, of course, is a very big country and its ports are in its east or south, while the shortest routes to Europe, geographically speaking, are from the western or central areas. Manufacturing companies have set up in those areas because it’s cheaper and labour doesn’t demand such high wages, but then they need to get their goods to market. Developing railways has been China’s answer. If you want to rule the world, you have to be able to reach it.

China can be confident that its neighbours, especially Russia and Europe, will be keen on its railway development. Railways cut transportation times and costs and where they exist, manufacturing facilities evolve. It’s not all for one-way traffic either, of course, because China needs the raw materials Europe can supply to feed its factories: minerals, machinery and chemicals. The Chinese government also provides subsidies for imports of between $1,000 (€840) and $5,000 (€4,200) for each Forty Foot (12.192 metres) Equivalent Unit (FEU), which is the size of a standard shipping container. There are also smaller twenty foot equivalent units, TEUs, of 6.1 metres that are used in international freight transport. It’s important because shipping costs have been skyrocketing for freight between China and Europe, according to Lloyd’s Loading List: “Multiple sources are reporting rates of US$10,500 (€8,800) per feu to secure capacity from China to European main ports, with China-UK rates now topping $16,000 (€13,440) per feu in what has become an auction for space.” The UK, Lloyd’s reports, has been especially hard hit, with carriers unwilling to use British ports, partly because of congestion. UK exporters can be asked to pay a fortune to transport their goods and only then if they get them to Antwerp first. One freight forwarder described it as “survival of the richest” while another predicted empty shelves in the UK where Chinese goods are concerned. Meanwhile, between 2011 and 2016, China’s provincial governments spent more than $300-million (€250-million) subsidising trains running between China and Europe.

According to the South China Morning Post, the COVID pandemic is actually working in China’s favour for trade. It reports that the China Railway Express, “a key project under China’s Belt and Road Initiative, operated a record 11,000 trains across Eurasia by early last November”. What’s more, “China continued to run a large trade surplus with the European Union in the first 10 months of year” (2020), indicating that westward shipments remain much larger than those going the other way. “The coronavirus may have pushed China’s freight shipments to Europe by rail to record highs, but far fewer trains have returned with European products, according to data from China’s state railway operator and external analysts,” the newspaper reports. Between 200 and 400 CE, it was the invention of the compass and the appearance of domesticated camels that fuelled trade along the Silk Road, but it took a long time. The rail links between China and Europe have developed in a mere decade, despite the massive and costly infrastructure required.

SPREADING FAR AND WIDE

The rail lines follow six main routes: the New Eurasian Land Bridge, linking Western China with western Russia; the China-Mongolia-Russia corridor, connecting North China to Eastern Russia via Mongolia; the China-Central Asia-West Asia corridor, linking Western China to Turkey via Central and West Asia; the China-Indochina Peninsula Corridor, which connects Southern China to Singapore via Indo-China; the China-Pakistan corridor, which links South Western China via Pakistan to the sea routes of Arabia; the Bangladesh-China-India-Myanmar corridor, connecting Southern China to India via Bangladesh and Myanmar. Furthermore, the maritime stretch of this latter-day Silk Road connects coastal China to the Mediterranean via Singapore-Malaysia, the Indian Ocean, the Arabian Sea and the Strait of Hormuz. Nobody ever said it’s not an ambitious plan. In fact, China now has the second longest rail network in the world. It’s not all plain sailing, however. The China-Pakistan corridor, for instance, has led to a row between the two countries. China had offered to lend Pakistan $6-billion (€5.05-billion), which Pakistan hoped would be at a preferential rate of less than 3%. However, China is reluctant to comply because it fears that local politics could delay the returns on its investment.

An analysis conducted in 2018 pointed out that in 2006 a standard container from Shanghai would take 36 days to reach Hamburg by rail. By the time the report was compiled that time had shrunk to just 16 days. As the old saying goes, time is money. It has also meant that, thanks to refrigerated containers, known as “reefers”, it is now possible to move perishable goods to and from Europe, not just laptops and mobile phones. One train operator, Far East Land Bridge, reported that the number of FEUs being shifted had risen from 21,900 in 2016 to 37,000 a year later, with cargo values of $160-million (€134-million) for 2017, a rise of $52-million (€43.66-million) over the previous year.

Another interesting point is that rail transport has been less disrupted by the pandemic while demand, especially for PPE-related goods, has soared by double-digit volumes in both directions: by 21% for goods bound to China from the EU, and by 44% for those going in the opposite direction. Figures also suggest the disparity between east-bound and west-bound freight is diminishing. Even so, the railway still has only a small share of the overall freight transportation business, despite that spectacular growth. Furthermore, the Chinese government has decided that rail freight will be the ‘primary supporting pillar’ for Chinese foreign trade and the operators of so-called ‘block trains’ are actively encouraged to co-operate closely with Chinese-owned cross-border e-commerce companies, especially with regard to logistics.

Block trains, also known as ‘unit trains’, are trains upon which all the freight wagons, cars or containers are carrying the same goods, loaded at one single loading point and carried to a single destination, without being broken up along the way or having their wagons separated and stored somewhere en route. With the use of ‘reefers’, the cold shipping of perishable goods has been developing, although the increased volume of meat from the EU to China did not involve rail transport. There are still too many administrative and infrastructure barriers along the way. However, with Russia now permitting food transport across its territory there have been trial journeys of European salmon from the Netherlands. It’s not straightforward and some obstacles remain, especially in Russia, but for perishable goods, the express railways shipping line now reckons on a journey time of 10 to 12 days between Xi’an and Hamburg, offering a viable alternative to costly air freight.

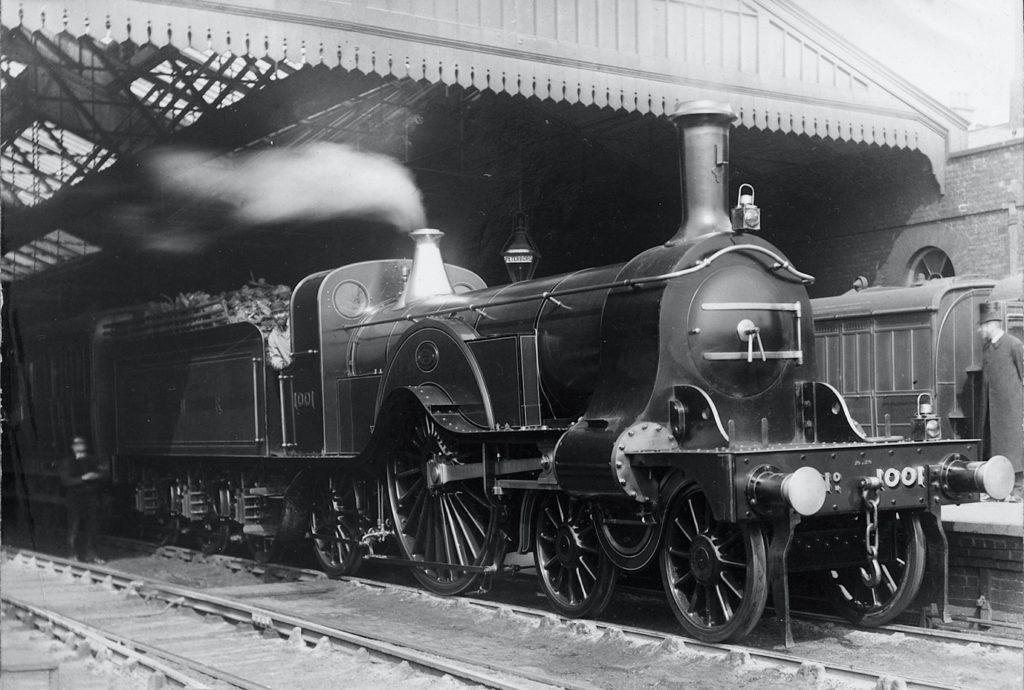

OBOR spans 78 countries and has been described by the Chinese government, not unreasonably, as “the project of the century”. It requires the co-operation of other countries, of course, but it is helping them to fund the construction work from which they will clearly benefit. In China’s case, obviously the rail expansion is economically valuable, but Beijing sees it not just as a way to boost domestic growth but also as a form of ‘economic diplomacy’. “By connecting the less-developed border regions like Xinjiang with neighbouring nations, China expects to bump up economic activity,” explains Investopedia. “OBOR is expected to open up and create new markets for Chinese goods. It would also enable the manufacturing powerhouse to gain control of cost-effective routes to export materials easily.” Developing railways doesn’t come cheap but it worked in 19th century England, where the cost of rail freight transport in 1870 was a mere tenth of what road transport rates had been in 1800. As a result, more goods and people travelled. By the 1840s, England and Wales were living through what history records as ‘railway mania’, with every member of parliament wanting to have a railway station in his constituency.

According to the UK’s National Archives, “In the 1840s ‘Railway Mania’ saw a frenzy of investment and speculation. £3-billion (€3.5-billion) was spent on building the railways from 1845 to 1900. In 1870, 423 million passengers travelled on 16,000 miles of track, and by the end of Queen Victoria’s reign (she died in 1901) over 1100-million passengers were using trains.” And, of course, little boys always loved trains, with their puffing, steaming engines the closest things they could find to the dragons of storybooks. Perhaps that’s why the Chinese love them, too.

STILL ON TRACK

It is hardly surprising, given that lesson from history, that participating countries such as Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan are very keen on OBOR, thanks to massive investments by China. Even Nepal, which is landlocked and therefore has difficulties in moving freight in and out, has signed up to participate, thus improving its connectivity with China, while Pakistan should benefit from the $46-billion (€38.66-billion) China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), connecting China to and through Pakistan giving access to Arabian Sea routes. While the development of OBOR benefits those countries through which it passes (or to which it is linked), it doesn’t take a great leap of imagination to see how it will reinforce and strengthen China’s economic and political power. Investopedia thinks it’s very possible that we will see increased use of the Chinese yuan as the currency of choice along the route of OBOR, which would be a welcome development as far as Beijing is concerned. It would give Xi even greater leverage. He should, perhaps, acknowledge one of Confucius’s analects, however: “He who exercises government by means of his virtue may be compared to the north polar star, which keeps its place and all the stars turn towards it.” I somehow don’t think the Uighurs or the people of Hong Kong would necessarily describe Xi as virtuous. The word ‘brutal’ springs more readily to mind for them, perhaps.

We must remember, too, a point I made earlier: yes, the plan is economically important for China, but it is primarily a political project. It will, hopefully, make those along the way a little richer, just as the proliferation of railways in Victorian England did. But it also strengthens the central power. If you think of all these fast-expanding routes as being like a spider’s web, there is no doubt who is sitting in the middle, alert to every twitch on a fibre. One twitch could come from the effect of the railway on population growth. Take the experience of Victorian England, for example. In the 18th century, England had been a largely agrarian society; the trains changed that, and surprisingly quickly. The population rose from 8.6-million in 1801 to 17-million by 1851 and to 22,3-million thirty years later, according to a report produced at Cambridge University. The birth rate continued to rise until 1881, with children largely viewed as assets to help with their parents’ jobs (much of it in agricultural work or in crafts such as weaving), but then began a long decline as children were increasingly seen as a burden that prevented their parents from working and thereby affecting the family income. The sharpest decline came in the professional classes, but ten years later there was a sudden rapid decline among those engaged in mining. It’s impossible to tell at this juncture if OBOR will affect birth rates in the countries through which it passes, nor whether it will cause an increase or a decrease if it does.

One way in which OBOR is helping China to overcome its difficulties concerns the Uighur people of Xinjiang, in East Turkistan. Such is their interest in the economic advantages they can see that even the Taliban has withdrawn its support for them. The Chinese offer to the Taliban is to make highways and connect all Afghan cities to each other. Other offers include energy projects to develop Afghanistan while the Taliban has to promise peace in return. It seems they’re rather more pragmatic than the old-style Mujahideen used to be. China is also interested, of course, in Afghanistan’s mineral wealth. Chinese companies had won contracts to mine copper and explore for oil but could not do so because of all the internal strife in the country. China would be keenly looking at working on the contracts further. As the Wife of Bath said in Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, “It’s all for sale”, by which she meant virtue, morals and standards, but I’m sure she would have included copper ore and crude oil if she’d known.

The Chinese Communist Party holds its centenary this summer and the refrain it keeps singing in celebration is that “the East is rising while the West is declining”. It’s hardly original, but the annual legislative sessions held in Beijing have been full of praise for China’s handling of the pandemic. The former party leader in the Xinjiang region in the far west of China has spoken to his fellow deputies at the National People’s Congress of “extraordinary accomplishments”. According to the South China Morning Post (SCMP), Zhang Chunxian

described 2020 as a “watershed year” for China.

“Since no country could escape the major test of the pandemic last year,” he is reported as saying, “this trend that the East is rising while the West is declining has become very obvious.” Obvious to him and the other deputies, anyway. He also spoke of the US “retreating”. Politics gives way to economics. Mau Zedong wrote in his ‘Little Red Book’: “Every Communist must grasp the truth, ‘political power grows out of the barrel of a gun’, but it also grows out of a pocket calculator and an ambitious plan.

The SCMP quotes Guo Shengkun, party secretary of the Central Political and Legal Affairs Commission, as going even further than Zhang Chunxian. “Chinese, of all ethnic groups,” he said, “experienced the extraordinary accomplishments achieved by our party, the country and the public. This was especially seen in the striking contrast of the order in the East and the chaos in the West, the rise of the East and decline of the West, and the ascendency of China and fall of the US.” That seems to be putting it a little strongly, don’t you think? The fall of Donald Trump is not the same as the fall of the entire country. He and his followers may believe that ‘Trump’ and ‘the United States’ are synonymous but they’re really not. Yes, a surprisingly large number of conspiracy theorists and believers in the loony-tunes branch of the far right may have invaded government buildings in a bid to overturn an election result but that’s not final, it didn’t succeed and nor is it exclusive to the US. Anyone remember Tiananmen Square?

Or how about present-day Hong Kong? Whatever Guo Shengkun may believe, there are people in China who are less than happy with the rule of Xi Jinping, even if they wisely keep quiet about it, and in history there have been others who disapproved of their leaders.

Mind you, China’s handling of the pandemic was exemplary and Beijing has a right to boast about it. Xi bragged in the official People’s Daily newspaper that the success in the pandemic was down to China’s political system and the choices the Chinese people had made. In a way, that could be right: when Beijing orders a lockdown people obey. To do otherwise would not be wise. Even so, Xi has a right to be proud.

“Now, when our young people go abroad,” he told members of an advisory committee, “they can stand tall and feel proud – unlike us, when we were young.”

Perhaps, but a little more transparency during the early stages, when the virus was first detected in Wuhan, might have prevented some of the 2.6-million deaths that SARS-CoV-2 has caused. The evidence suggests that China was not the cause of the pandemic, nor was the virus a biological weapon, spread deliberately. We can file such notions under “conspiracy theories” to satisfy racists. They explain why some university students, even post-doctoral students, of Chinese ethnicity have faced hostility and threats in the US, limiting their time spent on research: some people long to have somebody to blame and some are simply violent thugs who like to pick on minorities. It’s a sad fact of being human. But it’s pointless to point the finger of blame. When someone catches German measles they don’t go and shoot people in Berlin to get their own back.

MIXING THE MEANS

The OBOR project is not only a railway (or even several railways); it is a system that uses rail lines to link to other transport routes. For instance, the China-Europe railway connects to London via road and ferry, shipping from Duisburg via Rotterdam. It’s what’s called an ‘intermodal’ system, developing ports as well as rail lines. The China-Europe Land-Sea Express, operated by COSCO, uses the Greek port of Piraeus as its transition hub, connecting to the Croatian port of Rijeka, using an express shipping line, and then on to the rest of Europe by rail. The long-term strategy includes a direct railway connection, Piraeus-Belgrade-Budapest, for access to the European market. China agreed to lend to the Hungarian government the money needed to fund the work. Both governments are keen. Others in the shipping industry are engaged in expanding the north-eastern Asia-Europe intermodal connection through the far-eastern ports of Russia, Vostochny and Vladivostok. The freight carrier Maersk, working with Pantos Logistics, has been offering an inter-continental sea and rail shipping line to connect South Korea and Japan to Europe, Pusan (ocean freight)-Vostochny (trans-Siberian Railway)-Europe, halving the time it takes purely sea-borne freight to reach its destination. Shipping volume is reported to have risen by 30% since the pandemic arrived.

In addition to Maersk, RZD Logistics, FESCO and PCC Intermodal have launched their own multi-modal shipping service from North-East Asia to Europe using the Trans-Siberian Railway. For China, its long-term economic and political interest in South-East Asia has developed into a long-term vision of intermodal connections, joining manufacturing sites in South-East Asia with the valuable market of Europe by 2025. This means bringing two OBOR projects under one roof: the ‘West Land-Sea international trade corridor’ and the ‘China-Europe Railway’. In that way, the idea has attracted interest from the governments of Vietnam and Kazakhstan. A trial run from Dong Dang in Vietnam reached Duisburg in Germany in 22 days. In Victorian England, the railway network spawned factories and the growth of small towns into thriving cities right across its network. China has to get a good return on its investment; it’s been estimated that the total cost of completing the project could come to $1.2-trillion to $1.3-trillion (€1.01-trillion to €1.09-trillion) by 2027.

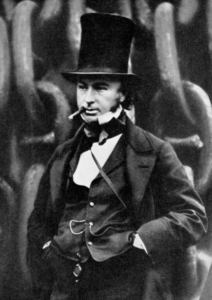

Coincidentally, the project is encountering the same problem the railway entrepreneurs faced in Victorian England. Most of the country followed George Stevenson’s standard gauge of 4 feet 8.5 inches, 1.435 metres, which is still used for 54.9% of railways around the world. Isambard Kingdom Brunel, however, preferred his “wide gauge” of 7 feet 0.25 inches (2 metres 1.2 centimetres) to aid safety at high speeds.

It’s said that Stevenson chose his odd gauge because he had experimented at nearby Killingworth Colliery, whose trucks of coal were horse-drawn along tracks that happened to have that gauge. During the railway mania phase and for several years afterwards, it meant trains stopping where the tracks met and the coaches or wagons being transferred onto appropriate bogeys. On China’s prestigious OBOR, that would not be practicable. China still uses Stevenson’s 1.435 metres (the managers of Killingworth Colliery should be proud) while Russia uses the old Tsarist Imperial gauge of 1.520 metres, as do Mongolia and Kazakhstan. In England, all railways (remember, there were not THAT many lines at the time, and the money they were making was phenomenal) had their tracks ripped up and replaced with the Stevenson gauge. If Brunel had won, the UK would have had high-speed trains rather earlier. Russia is unlikely to want to change all of its rail infrastructure, or even to be able to. In mainland Europe, a difference in gauges between France and Spain caused a similar problem. China is said to be developing high-speed trains that can adjust to either gauge as they go along, although there are still technical problems.

Rest assured, they will be overcome. China is a clever country with many ingenious engineers and inventors. Where the generation of wealth is concerned, ways are inevitably found. Where the pursuit of power and influence is concerned, China will not allow an annoying detail like incompatible gauge sizes to get in its way.

A Chinese train will be coming to (or at least through) a station near you in the very near future. Before you know it, the companies that make model trains will be offering an OBOR version, although it will require a lot of track: they’re very long trains. Think of the possible options for model buildings! Little boys will love it (quite a few little girls will, too; let’s not be sexist here) assuming their parents can afford it. Then again, we should remember another of Confucius’s analects: “In a country that is well governed, poverty is something to be ashamed of. In a country that is badly governed, wealth is something to be ashamed of.” And there’s another, similar one: “To be wealthy and honoured in an unjust society is a disgrace.” I wonder if President Xi will take note?