After weeks of attempts by Western leaders to negotiate through diplomatic channels, Russian president Vladimir Putin finally launched a massive military operation in Ukraine, in the early hours of Thursday 24 February. It amounted to a full scale invasion of that country. Nothing and no one could stop him. A few minutes before ordering his troops to attack, Vladimir Putin addressed his people and the whole world from his office in the Kremlin. It was a most incredible speech…it was a declaration of war !

Two days after recognising the independence of Ukrainian separatist territories in Donbas, he said he wanted to “defend” them against Ukrainian aggression. “I have decided on a special military operation,” Putin announced in a surprise statement on television, before 6 a.m. (0300 GMT). “We will strive to achieve demilitarisation and denazification of Ukraine,” said Russia’s strongman, sitting at a desk.

He repeated his unfounded accusations of a “genocide” orchestrated by Ukraine in the pro-Russian secessionist territories in the east of the country, stressed the call for help from the separatist leaders allegedly made the previous night, and reiterated the “aggressive policy” of NATO with regard to Russia and of which Ukraine was supposedly the tool.

Shortly later, a series of explosions were heard in Kiev, in Kramatorsk, a city in the east which serves as the headquarters of the Ukrainian army, in Kharkiv, Ukraine’s second largest city, and in Odessa, on the Black Sea. Air-raid sirens sounded every 15 minutes in Lviv, the western city where the United States and several other countries have moved their embassies.

But let us go back in time to March 18, 2014. Following the Winter Olympics that he had hosted in the Black Sea resort of Sochi, Russian president Vladimir Putin addressed the nation from the Kremlin before a large assembly of high ranking officials and parliamentarians.

He also signed the documents that officially reunited the Russian Federation and Crimea, the home base of Russia’s Black Sea Fleet. Crimea had seceded from Ukraine only two days earlier, on March 16. The Russian president gave a historic speech that was filled with references to several centuries of Russian history.

At the centre of his narrative was Crimea. Putin declared that Crimea “has always been an inseparable part of Russia” and that Moscow’s decision to annex it was rooted in the need to right an “outrageous historical injustice.”

That injustice had begun with the Bolsheviks, who incorporated lands that Russia had conquered, into their new Soviet republic of Ukraine. Then, in 1954, Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev made the fateful decision to transfer Crimea from the Russian Federation to Ukraine. And when the Soviet state collapsed in 1991, Russian-speaking Crimea was, according to Putin, left in Ukraine “like a sack of potatoes”.

Putin’s speech and the ceremony reuniting Russia with its ‘lost province’ came after several months of political upheaval in Ukraine. Towards the end of November 2013, demonstrations had begun as a protest against Ukrainian president Viktor Yanukovych’s decision to back out of the planned signing of an association agreement with the European Union. These soon turned into a large-scale protest movement against his government, known as the Euro Maidan protests.

By February 2014, clashes with Ukrainian police erupted that left over 100 people dead on both sides. On February 21, 2014, talks between Yanukovych and the opposition were brokered by outside parties, including Russia.

But a provisional agreement, intended to end the violence and pave the way for new presidential elections at the end of 2014, fell apart when Yanukovych suddenly fled the country and took refuge in Moscow. Meanwhile, in Ukraine, the opposition formed an interim government and set May 25, 2014 as the date for presidential elections.

At about the same time that Yanukovych left Ukraine, unidentified armed fighters who came to be known as the ‘little green men’ began to seize control of strategic infrastructure on the Crimean Peninsula. On March 6, the Crimean parliament voted to hold a snap referendum on independence and the prospect of joining Russia. On March 16, the results of the referendum showed that 97 percent of voters had opted to unite with Russia. It was precisely this referendum that Putin used to justify Russia’s annexation of Crimea.

Most foreign observers felt that the Russian president, by so doing, had dealt the severest blow to European security since the end of the Cold War.

As Western leaders argued over how to punish Putin for seizing Crimea and deter him from similar actions in the rest of Ukraine and elsewhere, many questions arose: Why did Putin do this? What does he want? Many commentators turned back to questions that had been asked nearly 15 years earlier, when he first emerged from near-obscurity to become the president of Russia: “Who is Vladimir Putin?” For some observers, the answer was clear: Putin was who he had always been—a corrupt, avaricious, and power-hungry authoritarian leader.

In their view, what Putin did in Ukraine was just a logical next step to what he had been doing in Russia since 2000: trying to tighten his grip on power.

They argued that annexing Crimea and the nationalist rhetoric Putin used to justify it were merely ploys to bolster his flagging public support and distract the population from problems at home.

Other analysts however saw Putin’s shift toward nationalist rhetoric and his decision to annex Crimea as evidence of new “imperial” thinking, and as dangerously genuine. Putin’s goal, they proposed, was to restore the Soviet Union or even the old Russian Empire.

But if that was true, where were the patterns and key indicators of neo-imperialist revisionism in Putin’s past behaviour? Many world leaders and commentators wondered what they had missed. Unable to reconcile their old understanding of Putin with his behaviour in Ukraine, some concluded that Putin himself had changed. A “new Putin” must have somehow appeared in the Kremlin.

BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH

If, in fact, Putin’s behaviour in the Ukraine crisis was really different from the past, it could provide an opportunity to understand him better. It has been argued that it is precisely when people break with previous patterns of behaviour that we can begin to gain an understanding of their real character. But patterns of past behaviour are often a poor predictor of how a person will act in the future. Contexts change and alter people’s actions. Pattern breaks are key for analysing individual behaviour. They push us to focus on the invariant aspects of the person’s self. They help reveal the hidden drivers, the underlying motivations, and what a leader values most.

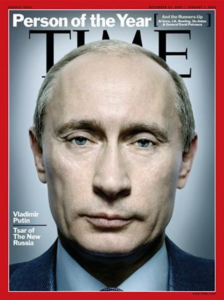

In 2006, Vladimir Putin was named ‘Person of the Year’ by Time magazine. Between 2013 and 2016, he was voted “most powerful person in the world” four times, by the influential American magazine, Forbes. From a very early age, he manifested the desire to become a personality apart. However, he has often left people with the feeling of being a man of many faces, hiding his true nature and feelings behind a succession of masks. His gaze, sometimes vague, sometimes intense, and his frowns or an impatient movement of his lips testify to an iron will, while he seems to slip from one’s grasp.

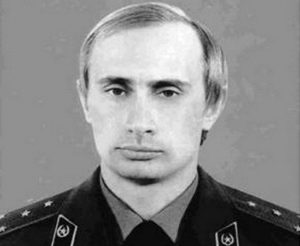

As a secret service officer, he undoubtedly learned to play more than one role and he has projected the image of a man who excels in the art of covering his tracks. Many have been struck by the ability of the future president of Russia to adapt his speech to the circumstances.

The most obvious reason we cannot take any story or so-called fact at face value when it comes to Vladimir Putin is that we are dealing with someone who is a master at manipulating information, suppressing it, and creating pseudo-information.

In today’s world of social media, the public has the impression that it knows, or easily can know everything about everybody. Nothing, it seems, is private or secret. Yet, after some twenty years, Vladimir Putin’s private life is kept under wraps and he still remains shrouded in mystery.

When he was named prime minister in 1999, he asked a few trusted journalists to write his official biography, and ever since, any research into Putin’s path to power has been strictly forbidden. We still don’t know some of the most basic facts about a man who is arguably the most powerful individual in the world and the leader of an important nation.

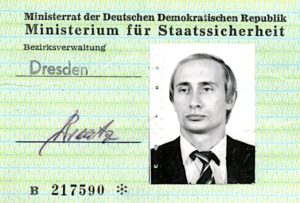

As the official story goes, Vladimir Putin was born in Leningrad – today’s Saint Petersburg – in October 1952 and was his parents’ only surviving child. The family lived in communal housing with the young Vladimir growing up very much in the shadow of World War II. After school, he studied law at Leningrad State University, graduated in 1975, and immediately joined the Soviet intelligence service, the KGB. After completing one year of study at the KGB’s academy in Moscow, he was posted to Dresden, in East Germany, in 1985 where he served as an undercover agent and liaison officer for the Stasi and KGB. It was in 1990, just as the USSR was on the verge of collapse that he was recalled from Dresden to Leningrad.

There, he moved into the intelligence service’s ‘active reserve’ and returned to Leningrad State University as a deputy to the vice rector. He became an advisor to one of his former law professors, Anatoly Sobchak, who left the university to become chairman of Leningrad’s city soviet, or council. Putin worked with Sobchak during the latter’s successful electoral campaign to become the first democratically elected mayor of what was now St. Petersburg.

But some biographers have noted his “often disreputable” skills acquired while in the KGB. For instance, he had corrupt companies pay dirty money to Sobchak and his staff on a number of occasions during his time at Saint Petersburg city council.

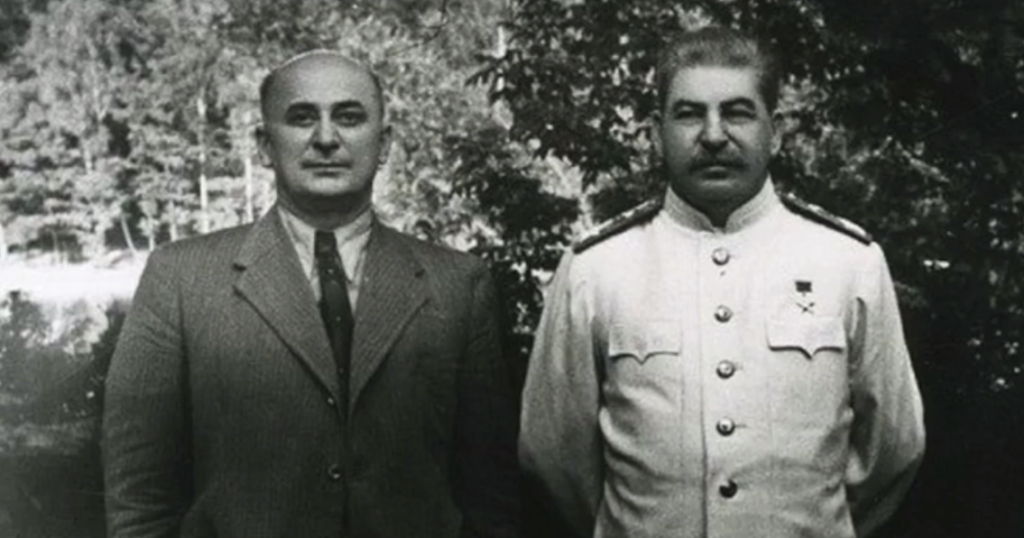

By all accounts Putin’s grandfather was a cook in the service of Stalin, and of Lenin before that. So, what is the grandson’s favourite recipe ? One may well be tempted to answer, “chaos, spiced with suspense and intimidation” !

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, 15 new countries, including the new Russian Federation came into being. In Vladimir Putin’s eyes, Russia had just lost 2 million square miles of territory. The government had to sell off nearly 45,000 public businesses such as energy, mining and communication companies that had been run by the communist regime. And it was chaos. The Russian economy was in a free fall and all these companies ended up in the hands of a few, extremely wealthy men…the oligarchs.

At the same time, the new Russian state was having a hard time establishing itself. Russia’s first president, Boris Yeltsin was highly unpopular for cooperating with the West, and to make matters worse, he was an alcoholic; many Russians felt he was an embarrassment.

In order to stay in power, he sought the support of these oligarchs, surrendering immense political power to them. This is when Vladimir Putin entered the world of politics.

In June 1991, he became a deputy mayor of St. Petersburg and was put in charge of the city’s Committee for External Relations. He officially resigned from the KGB in August 1991.

In 1996, after Mayor Sobchak lost his bid for re-election, Vladimir Putin moved to Moscow to work in the Kremlin in the department that managed presidential property. In March 1997, Putin was elevated to deputy chief of the presidential staff. He assumed a number of other responsibilities within the Kremlin before being appointed head of the Russian Federal Security Service FSB (the successor to the KGB), in July 1998.

Putin used his position to give special treatment to friends and allies in the private sector, helping them to structure monopolies and to regulate their competitors. He rapidly became a favourite among the oligarchs and assembled a support network of oligarchs and security officials, mostly fellow former KGB officers like himself. With their help, he rapidly ascended to the upper echelons of the new Russian state.

In August 1999, Vladimir Putin was named, in rapid succession, one of Russia’s first deputy prime ministers and then prime minister by President Boris Yeltsin, who also indicated that Putin was his preferred successor as president.

Yet this fierce nationalist felt that Yeltsin was letting the US dominate Russia and that NATO, the alliance that worked for decades to contain Soviet influence, would expand into the newly liberated countries and surround Russia. Putin’s goal then became to build a strong Russian state, one that would be both stable at home and capable of exercising more influence over its neighbours.

And he didn’t have to wait long…during the post-Soviet chaos, there was escalating violence in Chechnya, a region that had unilaterally seceded from Russia in the mid 1990s. Chechen warlords and terrorists were pushing into Russian territory and attacking the border. In August 1999, a series of deadly bombings killed more than 300 people in several Russian cities, including Moscow. Putin, the new prime minister, immediately blamed Chechen separatists for the attacks. He appeared regularly on television, claiming he will avenge Russia. The population rallied around him and his approval ratings jumped from 2% before the bombings to 45% after the bomb attacks.

Later, journalists uncovered evidence that suggested Russian security services could have been complicit in the Moscow bombings, perhaps knowing they would spark more support for a strongman like Putin. But a tightly-controlled official investigation rapidly quashed any dissenting theories. However, certain oligarchs who were not in good terms with Putin, such as Boris Berezovsky threatened to lay out documentary evidence that Russian security services were involved in the apartment house explosions of September 1999.

Be that as it may, Russia launched a popular but devastating war in Chechnya. The capital, Grozny was levelled by such intense bombing that close to 80,000 people were killed. Putin had attained his objective; in less than one year, Chechnya was successfully brought back under Russian control.

On December 31, 1999, Putin became acting president of Russia after Yeltsin resigned. He was officially elected to the position of president in March 2000 and began to shape the Russian state to his vision. Patronage and corruption remained some of his key tools, but he quickly suppressed the oligarchs under his rule. Those who supported him were rewarded and those against him imprisoned and harassed. The most striking example was Mikhail Khodorkovsky, former oil magnate and at one point, Russia’s richest man. He was convicted to 14 years in jail on a charge of embezzlement. This was seen as a vendetta from Putin, for Khodorkovsky getting involved in opposition politics.

Putin served two terms as Russia’s president from 2000 to 2004 and from 2004 to 2008, before stepping aside – in line with Russia’s constitutional prohibition against three consecutive presidential terms. He was named prime minister by his hand-picked successor and friend, Dmitry Medvedev.

He very soon imposed a vertical hierarchy, with himself as the strong, undisputed leader of a state which he ambitioned to bolster. He developed a glamorous cult of personality around himself to give Russians the impression that after years of struggle, they finally had a real leader who is in charge.

He gradually adopted a growingly nationalist stance, positioning himself against the West both in foreign affairs and on social issues. As an alternative to what he sees as Western decadence, Vladimir Putin offers the image of a strong Russia, a disciplined Russia. He sees himself as a guide not just for his own people, but for anyone around the world who believes in conservative values.

In March 2012, Putin was re-elected, once again amid chaos, to serve another term as Russia’s president until 2018.

This was made possible thanks to a constitutional amendment, again pushed through by then-President Dmitry Medvedev in December 2008, extending the presidential term from four to six years. He doubled down on his authoritarian style of governance at home and his militaristic strategy abroad, but in both cases, he displayed his mastery of controlling information.

Since he first took office, Putin has kept a tight leash on Russian media. Essentially, all news outlets are state-owned propaganda machines and his regime decides which stories air and how, always depicting him as the strong Russian, nationalist leader. In 2012, he cracked down on human rights and civil liberties, making clear there was no room for dissent in his Russia.

Unsurprisingly, he was re-elected for a fourth term as president, obtaining 76% of votes. And following the constitutional amendments that were approved in July 2020, Putin can potentially remain in office until 2036.

These basic facts have been covered countless times in books and newspaper articles over the years, yet there is still some uncertainty in the sources about specific dates and the sequencing of Vladimir Putin’s professional trajectory. This is especially the case for his KGB service, but also for some of the period when he was in the St. Petersburg mayor’s office, including how long he was technically part of the KGB’s ‘active reserve.’

MYSTERY MAN

Personal information, including on key childhood events, his 1983 marriage to Lyudmila Ocheretnaya (whom he divorced in 2013), the birth of two daughters in 1985 and 1986, and his friendships with politicians and businessmen from Leningrad/St. Petersburg is astonishingly meagre for such a prominent public figure.

For example, his wife, daughters, and other family members are conspicuously absent from the public domain. Information about him that was available at the beginning of his presidency and the period leading up to it seems to have been suppressed, distorted, or lost.

In fact, very little information concerning Vladimir Putin’s life is definitive, confirmable, or reliable.

Although there are many rumours circulating that Putin is a corrupt multi-billionaire, it would be impossible for investigators to prove it or track his personal fortune. Moreover, some Putin specialists speculate that he himself is behind the rumours, in order to keep kleptocrats and businessmen guessing. Putin’s private life remains enveloped in a mantle of dense fog.

Journalists and media outlets that report on his private affairs suffer swift and deadly reprisals. In 2020, Proekt Media, specialising in investigative journalism revealed the existence of Svetlana Krivonogikh, a 45 year-old Russian millionaire with whom Putin allegedly began an affair while still married to Lyudmila Ocheretnaya. The journalists further linked her financial assets to Putin, after the Panama Papers in turn, revealed the extent of her assets overseas. And last but not least, it was alleged that Putin had also fathered Krivonogikh’s daughter. Proekt was shut down immediately by the state media watchdog.

Putin is sometimes credited with an affair here and there, but nothing really substantial comes of all that. No woman ever accompanies him on the side-lines of international events. His health is not the subject of any official report, despite unexplained absences which make Moscow rustle with rumours.

In 2009, Russian publication Moskovsky Korrespondent reported that Putin was having an affair with Alina Kabaeva, a 26 year-old former Russian Olympic gymnastics gold medallist and a State Duma deputy from the United Russia Party. The newspaper was promptly shut down. Other news reports had noted that the couple wore wedding rings during the 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi, where she was a torchbearer during the opening ceremony.

A NEW RUSSIA

“There is no such thing as a former intelligence agent,” says a Russian proverb, and Vladimir Putin seems to continually demonstrate the validity of the saying.

To avoid national disaster, Putin advocated a single antidote when he was elected president in March 2000 : the rebirth of state structures destroyed by post-communist chaos. The Russian president divided the country into seven super-regions, thus trying to strengthen the state.

He also considered the former republics of the USSR to be “a zone of vital interest” for Moscow. To impose his plans, Putin has consciously brandished the threat of Russia breaking up, presenting it as a collection of islands run by the local mafia and oligarchs. His approach however, remains marked by his past as a KGB officer: gagging the press through closures and other restrictions, he defines his objectives, and to achieve them, all means are good.

Thus Russia has begun to live in a kind of ‘controlled democracy’.

What is the role of the state in the new Russia? Are democratic rules to be respected?

Is Russia marked by neo-imperial tendencies aimed at, at least, a partial reconstitution of the USSR? These were the questions that President Putin addressed during his two terms of office from 2000 to 2008.

This period in Putin’s presidency was marked by a return to the heritage of the USSR. Its framework was, as in every totalitarian country, its secret police, the KGB. Once the political system had collapsed, the security apparatus remained. The FSB (the new Russian secret service) ended up wearing the clothes of the KGB.

Vladimir Putin has famously declared: “The collapse of the Soviet Union was the greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the 20th century. For the Russian people, it was a real tragedy. Tens of millions of our citizens and compatriots found themselves outside the Russian borders. What’s more, the epidemic of disintegration also spread within Russia itself. “

According to Vladimir Putin, the new Russian national identity, is that of an empire-building people. The essence of this idea took its roots from the mid-nineteenth century, from a form of state organisation, characterised by a central power, an effective mechanism of succession and the presence of a strong leader. Marked by the influence of Orthodoxy, this became the ‘de facto’ state ideology of post-Soviet Russia.

The extent of the crimes of the totalitarian system was never recognised and Putin therefore rehabilitated both the tsarist past and the Soviet past, to build a historical continuity.

Relying on his expert advisors in public relations, he used – in parallel with his hunt for oligarchs – the phobias inherited from the Stalinist period, in particular the visceral fear complex of the population, known as ‘The besieged fortress ideology’, reflecting the mass perceptions of Russians facing hostile forces from outside; in this case Chechens, Georgians, NATO and the West generally. After the 1917 revolution, Soviet leaders seemed to think that this sentiment would sooner or later compel Western countries to attack. But today’s ‘besieged fortress’ mentality could be more dangerous than the Soviet one. The state is trying to convince its citizens that foreigners hate Russia simply for what it is and for the good it is trying to bring to an ungrateful world.

This process gained momentum under Vladimir Putin, with the restoration of the Soviet anthem, the glorification of the KGB, the rewriting of history in favour of its Stalinist version, and the gagging of the press and censure of the West, which were both accused of giving lessons in democracy to Moscow, with the unavowed aim of weakening the state.

But more than two decades into the 21st century, Vladimir Putin is still at the helm, making him the longest serving head of state since Stalin. However, Russia still seems to be searching for itself, and its 70 year-old leader still remains largely unknown.

With Russia controlling 17% of the world’s gas reserves, oil and gas have been the main sources of economic performance in the Putin era. In the field of international relations, Russia has sought to regain its former influence by wielding the gas weapon and associating with authoritarian regimes in Central Asia. On all external fronts, the Kremlin was determined to make people forget the humiliation of the 1991 collapse of the Soviet Union and the more recent democratic revolutions in Ukraine and Georgia that reduced its influence.

President Putin has openly announced his intention to put Russia back at the centre of world politics. His strategy: disrupt the rules of the game wherever he can. Somewhat isolated after its intervention in Ukraine, Russia has used the Syrian conflict as a springboard to regain power in international affairs. The all-powerful man in charge at the Kremlin unashamedly uses off-field methods of destabilisation, and resorts to its shadowy networks of operatives in Europe, the United States, in the post-Soviet republics, in Africa, in Asia, and even in the Far North.

All means are good: interference in elections, elimination of opponents, political and economic pressure, cyber-attacks and military interventions. Faced with this global offensive, a divided, hesitant and at times, even a benevolent West seems unable to find an effective response. Yet Moscow is in the process of shaping a tougher, more unstable and conflictual world. A world where the balance of power prevails over cooperation, where human rights are eroded, where democracy yields to autocracy. A world faced with the ambitions of the Kremlin; an ambition that Vladimir Putin is striving to impose through his strategy of chaos.

Vladimir Putin has long since eradicated any form of internal opposition. Candidates who are seen as a threat to power are systematically prevented from running for elections under various pretexts. Or worse. Boris Nemtsov, former governor of Nizhny Novgorod and a former minister under Boris Yeltsin, who had become the most vocal critic of Vladimir Putin, was shot several times from behind in February 2015, on the Bolshoy Moskvoretsky Bridge, close to the Kremlin walls. He was due to speak two days later at a peace rally against Russian involvement in the war in Ukraine.

Five years later, in August 2020, Alexeï Navalny, a virulent critic of the regime’s corruption and number one opponent of the Kremlin was the victim of a highly publicised poisoning attempt by Russian intelligence agents, as he was about to board a flight to join his supporters in Siberia. In Germany, where he was transported in a coma at the request of his wife, doctors confirmed that they had found traces of Novichok in his urine and blood, as well as on the water bottle in his possession. This powerful military nerve agent had already been used in 2018, in the attempted murder of the former double agent, Sergei Skripal in England.

In both cases, the elimination and attempted elimination of the two Russian opposition figures correspond to specific events. Just as the murder of journalist Anna Politkovskaya on October 7, 2006 – Vladimir Putin’s birthday – was related to the Russian-Chechen war, the murder of Boris Nemtsov, who was about to reveal accusatory documents on Putin and the war, was linked to Ukraine. And the poisoning of Alexei Navalny is directly linked to Belarus. What Vladimir Putin fears more than anything is a contagion of protest movements in Russia, especially when these emanate from populations in neighbouring countries.

Even when suspected of the worst, secret service agents are rewarded. Andrei Lugovoi was promoted to MP after the polonium poisoning of Alexander Litvinenko, a former Russian intelligence officer who died in London in November 2006. Others are welcomed as heroes, like the sleeper KGB agents Andrei Bezrukov, alias Donald Heathfield and Elena Vavilova, alias Tracey Foley, who were expelled from the United States in 2010. On their return to Russia, the couple were received with full honours by president Putin in person.

SAVIOUR OR ANNIHILATOR ?

“It’s better to be hanged for loyalty than be rewarded for betrayal” Vladimir Putin

How a leader sees himself often defines the destiny he seeks for his nation. Vladimir Putin sees himself as the liberator of the Russian soul, a mythical warrior confronting powerful empires.

Putin, who is often referred to as ‘the Tsar’ by his admirers and detractors – an honour he ostensibly belittles – is on a mission to restore his country to its former glory as an empire and a superpower. He wants certain of the former satellite states of the Soviet Union, notably Ukraine, to return to the fold and to rule them like Stalin, but without the same ideological trappings. When he became president, Putin told young Russian troops that their task was to “restore the honour and dignity of Russia.”

Possibly driven by a desire for revenge after the erasure of Russia as a central player in a bipolar world, Vladimir Putin steadily increased his grip on Russian society, just as he did on the neighbouring countries considered as posing a problem. In 2008, after a blitzkrieg campaign lasting only a few days, Georgia was amputated of 20% of its territory after Moscow unilaterally recognised South Ossetia and Abkhazia as independent states. In 2014, Russia simply annexed the Ukrainian territory of Crimea while an armed conflict – unresolved to date – has ravaged the Donbass region of eastern Ukraine and resulted in an estimated 14,000 deaths.

He also bolstered his aggressive foreign strategy. He used traditional military methods such as sending weapons and fighter planes to help Syrian dictator Bashar al-Assad fight a bloody civil war. But Putin’s regime has also developed and fostered the most effective cyber army in the world and it has used it to wreak havoc in the West.

State-sponsored hackers have stolen classified US information, hacked politicians’ email accounts, even totally shut down Georgia’s internet while Russian troops invaded. And of course, they tried to sabotage the American presidential campaign in 2016. Russian hackers also launched propaganda campaigns in support of right-wing candidates in Europe, including an attempted sabotage of the French presidential election of 2017. With all of this, Putin hopes to exploit and deepen the political divide in Western democracies.

The strongman of the Kremlin denounces the encirclement of Russia by the forces of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), but above all he denies the right of the former republics and satellites of the USSR to freely choose their political destinies.

And the old antagonism against the United States that has been rekindled, now extends to all of Europe as Vladimir Putin discovers that despite his best efforts to drive a wedge between the twenty-seven members of the European Union, a consensus on decisive sanctions in reaction to events in Ukraine remains intact.

The world erupts in protest, but Putin doesn’t give in; he sees his aggressive foreign policy successfully weakening his neighbours while also rallying Russians around him. But he has achieved all this at the expense of his own people. His invasions have prompted harsh sanctions from the West, barring Russian businesses from trading in Western markets. The Russian currency has plummeted in value and the energy industry that Russia relies on so heavily is under heavy strain, and it is hard to imagine how Russia can continue normally under these circumstances.

Abandoning the ‘duplicitous’ West, Putin tends to see himself as Eurasian rather than European. This became evident during the Valdai summit in 2019, held in a gigantic hotel in the alpine ski resort of Rosa Khutor in Krasnodar Krai, Russia.

The Russian President was accompanied by the President of Azerbaijan Ilham Aliyev, President of Kazakhstan Kassym-Jomart Tokayev, President of the Philippines Rodrigo Duterte and King Abdullah II of Jordan. The summit, established in 2004, is a private gathering of Russian and international politicians, thinkers and government officials mostly from China, Iran, Pakistan and India, as well as some Europeans.

The five leaders together are meant to represent a unified Eurasia – a new economic and geopolitical entity, which Russia wishes to lead. Putin’s hostility towards the West and his newfound complicity with China are the two new pillars of his thinking. Certain analysts believe that Russia, having understood that it could not reproduce China’s economic miracle, wants to manipulate it for its own benefit.

In February 2022, Putin travelled to Beijing and was busy pressuring Chinese president Xi Jinping for support – China backed Russia’s demand that NATO refrain from expanding.

The Russian president is playing a cunning but dangerous game. While he hopes he can both ride and control the Chinese dragon, Xi Jinping probably has his own plans to take over the planet.

In the meantime, president Putin’s control over Russia and his popularity are not as weak as some in the West make out. He presents himself as the champion of Russian conservative values, supported by the Russian Orthodox Church. He likes to be seen as a man of the people, a fellow traveller from the era of Soviet deprivation to a prosperous Russia.

He stirs up and exploits Russian nationalism – after the annexation of Crimea, he spoke of the military victories of the former Russian Empire on land and sea. Despite the arrest and imprisonment of critics among artists, billionaires and rock stars, he remains popular with his people.

So, now that Putin has sent in his troops to invade and possibly annex Ukraine, what form will the Western retaliation take ? Short of direct military involvement, US president Joe Biden, European Union leaders, as well as other Western heads of state have responded with extremely severe economic sanctions on Russia that are hoped will prove decisive. The human cost of these sanctions however could be immense.

What should perhaps be given more public attention is Moscow’s response, once it has been hit by the Western sanctions which will affect Putin and his oligarch cronies. But the Russian president is not without recourse. Russia is the world’s third largest oil producer after the United States and Saudi Arabia, and the world’s second largest producer of dry natural gas after the United States. Around 40% of Europe’s natural gas comes from Russia. If Europe opposes Putin, Russia can throttle winter energy supplies, causing deep distress on the continent.

And Russia is also a key exporter of other critical natural resources which, if disrupted, can have major knock-on effects in other markets. And as we now know after the US elections in 2016, Russia also has powerful cyber-hacking capabilities to disrupt government, private security and financial systems in the US and Europe.

So far, the West has been lucky to avoid open warfare in cyberspace. There have of course been cyberattacks, intelligence operations and online crime, but open warfare in cyberspace has not yet taken place.

There is also the possibility of Russia stepping up its campaign of political warfare. Moscow could ramp up its efforts to exacerbate existing divisions within European countries and the United States, including through online manipulation. Moscow has demonstrated its ability and interest in intervening in elections, and although it has so far refrained from intervening overtly, it could change course and move on to something more direct.

Would the Russian president risk initiating bolder and more aggressive actions, seeking to increase the pressure elsewhere? This is where the dynamics of escalation become more concerning. Crises and responses tend to create their own inertia and momentum.

Some are of the opinion that Putin believes chaos is the fundamental energy of power, because only a strong leader who overcomes chaos can bring stability to a country and a society. Even if it involves creating that chaos himself; this probably explains why he invaded Ukraine.

Putin’s declaration of war was accompanied by a warning to Westerners who might be tempted to intervene, threatening them with “consequences that you have never experienced before in your history” . These are words that are difficult to believe possible on the part of the leader of a major nuclear power and a permanent member of the Security Council. These are the words of an angry man who denied the very existence of a Ukrainian identity before declaring war. The world probably underestimated the determination of an aging dictator, obsessed with taking revenge on history.

In the meantime, Ukraine is alone against Russia. The Ukrainians have known this from the outset, they are alone despite all the proclamations of solidarity, the last-minute arms deliveries and the first sanctions against Russia. This war is a global disaster but it is the Ukrainians who will obviously suffer most from the Russian firepower.

This conflict has thrown us into a different world and a different time . But Putin is committing the irreparable here… he is plunging the world into a new cold war which will take years to overcome.

Be that as it may, the unprovoked military assault on Ukraine and tragic loss of human lives will be Vladimir Putin’s biggest challenge so far. It will be a turning point for Russia, and surely determine his position and that of his country in the world hierarchy…or it could destroy them both.

On 27 February, the fourth day of the conflict, Russian and Ukrainian officials agreed to hold emergency talks at a location on or near the Belarus-Ukraine border, despite Vladimir Putin’s defiant and ominous gesture; ordering his defence minister and chief of general staff to put Russia’s nuclear forces on ‘special alert’ in response to what he described as Nato “aggression”.

So, who then is the real Vladimir Putin? A megalomaniac with a death wish or a master of illusion and realpolitik?…Or a man completely apart? We may soon find out.