In 1766, Sweden became the first country in the world to introduce a constitutional law to abolish censorship.

To commemorate this event, the Swedish Tourist Association launched what became known as the ‘Swedish Number’ in April 2016.

This was a telephone number – now discontinued – that connected callers from all over the world to random Swedes, anywhere in Sweden to talk about anything they wanted…anything at all.

Using Swedish citizens as ambassadors to answer the calls, the Swedish Tourist Association wanted to introduce citizens of the world to the true culture, nature and mindset of Sweden and its people.

To create ‘The Swedish Number’, the Swedish Tourist Association partnered with Intelcom, a leading provider of contact solutions, to create one of the largest switchboards in the world that supported incoming phone calls 24 hours a day, 7 days a week.

Their cloud-based contact centre was used to register ambassadors and connect all calls. The switchboard was designed to randomly choose one of the Swedish ambassadors for each call.

In troubled times, many countries try to limit communication between people, but Sweden did just the opposite. So instead, it became the first country in the world with its own phone number which gave Swedes the opportunity to answer the calls, express themselves and share their views on any subject they chose.

Even the Prime Minister, Stefan Löfven took calls for ‘The Swedish Number’ on April 14, 2016 and spoke to a number of – sometimes – bewildered citizens from around the world.

This level of openness and personal freedom is hard to come by in the world today and countries that do enjoy them are of course, keen to preserve them.

Prime Minister of Sweden Stefan Löfven answering the Swedish Number

Together with economic and social policies, as well as cultural practices, Sweden is firmly rooted in what is known as the ‘Nordic Model of social democracy’, an object of fascination and almost a sort of bellwether for the health of social democratic politics around the world.

A PANDEMIC STRIKES

Sweden caused a global stir and came under scrutiny with its controversial approach to fighting Covid-19.

Instead of tight lockdowns, Swedish authorities encouraged citizens to use common sense, work from home if possible, and not gather in crowds over 50. Primary schools stayed open, as were bars and restaurants, with images showing people enjoying drinks and crowding streets.

According to health authorities, the aim was to slow the pace of the virus.

Sweden, which has a population of about 10 million, has in this manner avoided overwhelming its health care system so far.

But instead of the slow burn among healthy people that the Swedish leadership had wanted, the virus has ripped through the nation’s nursing homes.

Other European nations expressed concern about Sweden’s relatively “soft approach” to fighting the coronavirus but Prime Minister Stefan Löfven, during a press conference in mid-May, defended his country’s strategy, pushing back on the notion Sweden has taken a “business as usual” attitude toward the pandemic.

“Life is not carrying on as normal in Sweden,” he said. “Many people are staying at home, which has had a positive effect on limiting the spread of the virus. Of course, we are painfully aware that too many people have lost their lives due to COVID-19.”

He did acknowledge Sweden’s estimated 3,582 deaths, which was far higher, per capita, than its Scandanavian neighbours Finland, Norway and Denmark, who all took a stricter approach.

But he was also quick to point out that Sweden is constitutionally different from many other democracies.

Stefan Löfven © Trausti Evans

Critics who deplore Sweden’s so-called lax approach to Covid-19 do not seem to understand that this approach is to a great extent determined by fundamental constitutional constraints.

By law and by tradition, Swedish politicians cannot tell the various government agencies what to do, and these agencies count relatively few political appointees among their staff.

There is a famous quote from US President Dwight Eisenhower in 1960 where he said: ‘Sweden exemplifies paternalistic socialism which gives rise to high rates of suicide and drunkenness, and a lack of ambition is discernable on all sides !’

However, Stefan Löfven, the 33rd Prime Minister of Sweden quite clearly contradicts that particular image.

Stockholm Central station © Arild Vagen

BEGINNINGS

Stefan Löfven was born on 21 July 1957 in Aspudden, a southern suburb of Stockholm.

His father had already died and his mother, unable to raise two children on her own without a sufficient income, placed Stefan in an orphanage when he was 10 months old.

Sometime later, he was taken into the care of foster parents who resided in the town of Sollefteå, in mid-northeast Sweden.

At the time of his adoption, it had been agreed that his birth mother would regain custody of him when she was able to. However, she never came to take him back.

His foster father, Ture Melander was a lumberjack and later a factory worker, while his foster mother, Iris Melander, was employed as an in-home caregiver.

And it was only after meeting Ulf, his long-lost brother, that the young Stefan found out his real name of Löfven.

He began his schooling in Sollefteå and later attended the local High School before embarking on a 48-week welding course at a career training centre in Kramfors.

Despite the financial difficulties he faced, he enrolled at Umeå University, in northeastern Sweden and began a course in social science ; however, he dropped out after 18 months and went back to study various trade union courses.

THE LURE OF POLITICAL ACTIVISM

In 1967, Löfven was drafted into the Swedish Armed Forces for his mandatory military service. He was assigned to the Swedish Air Force and served as as a munitions systems specialist until 1977.

On his return to civilian life, he had to find a job and it was in the northern port city of Örnsköldsvik that he had the opportunity of putting to the test his knowledge and skill as a welder with military vehicles manufacturers, Hägglunds & Soner.

It was also during this period that he met his future wife, Ulla Margareta who was active as a representative for the local branch of a trade union.

Stefan Löfven and wife © Frankie Fouganthin/Wikicommons

A leader by nature, with a keen sense of social justice, he soon became a favourite among his group of workers who elected him as their representative in the union.

With his leadership qualities, it was only natural that he went on to hold a succession of posts in the Swedish Metalworker’s Union.

He rose through the ranks to become a member of its national council. He was elected deputy member of its executive board (1989–95), its vice president (2002–05), and ultimately the president (2006–14) of IF Metall, the union formed through the merger of the Swedish Metalworkers’ Union and the Swedish Industrial Union.

But Stefan Löfven’s political career began in earnest when, with the strong support from union members, he was appointed as an executive member of the Swedish Social Democratic Party (SAP).

Founded in 1889, the SAP is the oldest political party in Sweden and has led successive governments for most of the period since 1932.

In fact, Löfven’s admiration for this party goes back a long way. At the age of thirteen, he became a member of the Youth League of the party and was active in various capacities throughout his teens.

Ultimately, Löfven’s involvement and subsequent total immersion in party politics owed very much to the inspiration provided by the revered Social Democratic Prime Minister, Olof Palme who was assassinated in Stockholm in 1986.

Olof Palme © Government.se

The major breakthrough for Stefan Löfven came in January 2012.

Following a damaging article published by a Swedish newspaper in 2011, claiming mismanagement of public funds, the then leader of the Social Democratic Party, Håkan Juholt handed in his resignation.

The executive board of the Social Democratic Party unanimously elected Stefan Löfven as its leader in an internal ballot. It was in April 2013, that he was officially confirmed as the new leader at the party’s annual congress.

What’s more, following this move, Löfven also became the leader of the opposition in the Swedish Parliament – the Riksdag – despite the fact that at the time, he did not have a seat.

BUMPY RIDE TO THE TOP

Henceforth, the face of the Social Democrats would be that of its leader, Stefan Löfven who led them into the 2014 Swedish general election, as well as those for the European Parliament.

Despite losing one seat, the Social Democrats retained their position as Sweden’s largest party in the EU parliament.

However, the Swedish general election resulted in a hung parliament.

Although the party succeeded in ousting the centre-right government of Prime Minister Frederik Reinfeldt which had ruled since 2006, the overall result was far from satisfactory.

Having won some 31% of the vote, the Social Democrats announced that they would be forming a minority government with the Green Party, under the premiership of Stefan Löfven who was duly elected to the post of Prime Minister in October of that year.

Being a pragmatist and recognising the relative weakness of the coalition in power, Löfven announced that he wanted a bipartisan agreement between the government and Alliance opposition parties based on cooperation and not on conflict.

He promptly announced his government’s top priorites : a reduction in unemployment, improvements to the education system and an even more efficient social security and pensions infrastructure.

The newly-formed Swedish government faced a severe crisis soon after taking office and all but fell in December 2014. Parliament rejected the proposed budget and Löfven was forced to call for snap elections the following March.

But he was fully aware that this would result in important gains for the right and especially far-right parties. So, putting all his negotiating talents to use, he succeeded in striking a deal with the opposition Alliance which, at the time, was led by the Moderate Party.

Swedish National Assembly © Johan Fredriksson/Wikicommons

It was agreed that the government would remain in power on condition that it accepted the budget proposed by the opposition.

Plans for the snap election were scrapped as both the government and the opposition Alliance worked hard to keep the far-right and anti-immigrant Sweden Democrats (SD) on the sidelines.

THE MIGRANT CRISIS

In 2015, Europe witnessed the arrival of some one million refugees, fleeing war zones and the political turmoil in the Middle East and Africa. Due largely to the country’s generous welfare system and its open society, Sweden experienced the largest per capita influx for any country as over 160,000 migrants applied for asylum, overwhelming its social service facilities.

Stefan Löfven, Chairman of the Social Democratic Worker’s Party, summer speaks in Vasa Park in Stockholm on 25 August 2013 © Frankie Fouganthin/Wikicommons

This crisis, coupled with the November 2015 terrorist attacks in Paris that resulted in the deaths of over 130 people incited the far-right Sweden Democrats to not only accuse the migrants of depleting the welfare system but also to exploit the fear in the population that Islamist terrorists were entering Sweden, posing as refugees.

The government had no choice but to begin tightening Sweden’s open borders and to harden its policies on immigration.

However, even after denying refugee status to around 80,000 asylum seekers, Löfven’s government continued to advocate for his party’s and his country’s traditional support for an inclusive social welfare programme.

Despite these very serious challenges, the Swedish government forged ahead. Throughout Löfven’s premiership, the economy experienced an annual growth of over 2% in GDP, inflation remained low and the unemployment rate fell from 8.0% in 2014 to 6.3% in 2018.

But the downside was the increase in violent crime. Although much of it was thought to be gang-related, the far-right Sweden Democrats accused asylum seekers and blamed the government for its lax immigration policies.

Stefan Löfven on the way to the Social Democratic Party Headquarters © Frankie Fouganthin/Wikicommons

The 2018 general election was fast approaching, and the Sweden Democrats were already looking forward to a populist anti-immigration backlash that would put them firmly in the role of kingmakers in parliament.

But things didn’t quite work out the way they wanted them to.

All the parties that made up the government coalition refused any alliance with the Sweden Democrats whom Löfven described as : ‘A neo-fascist, single-issue party which respects neither people’s differences nor Sweden’s democratic institutions.’

However, although Löfven’s Social Democrats came first at the close of the polls, their 28.5% share of the vote proved one of the party’s worst performances to date. In fact, the government coalition as a whole managed only about 40% of the vote ; clearly an insufficient figure to establish majority rule.

A demonstration against the Sweden Democrats in October 2010

With two weeks remaining in the current government term, Löfven rejected the opposition’s call for his resignation. This led to a vote of confidence towards the end of September 2018 which he lost. This set the stage for long, drawn-out negotiations to determine who would govern Sweden.

Sweden had to make do with a caretaker government and Prime Minister until finally, in January 2019, an agreement was reached between Löfven’s Social Democrats, the Greens , the Liberals and the Centre Party. The Left Party agreed to abstain from voting against Löfven.

This agreement resulted in the reinstallation of the minority coalition government of the Social Democrats and the Green Party which was officially sworn in on 21 January 2019.

NORDIC MODEL IN ACTION

Globalisation has been hotly debated in the world for quite a while now. Some reject it for its potential negative impacts, but many see globalisation as a force that should be embraced, with potential benefits for jobs, wages, social security, trade and critical global issues like climate change.

Among EU leaders, Stefan Löfven has probably a unique perspective on working people’s concerns, having started his career as a welder on the factory floor, rather than gliding into politics with a degree from an elite university or a top law firm.

Unsurprisingly, he is an ardent advocate of this view, which corresponds almost exactly to the beliefs and principles of what has become known world-wide as the Nordic Model.

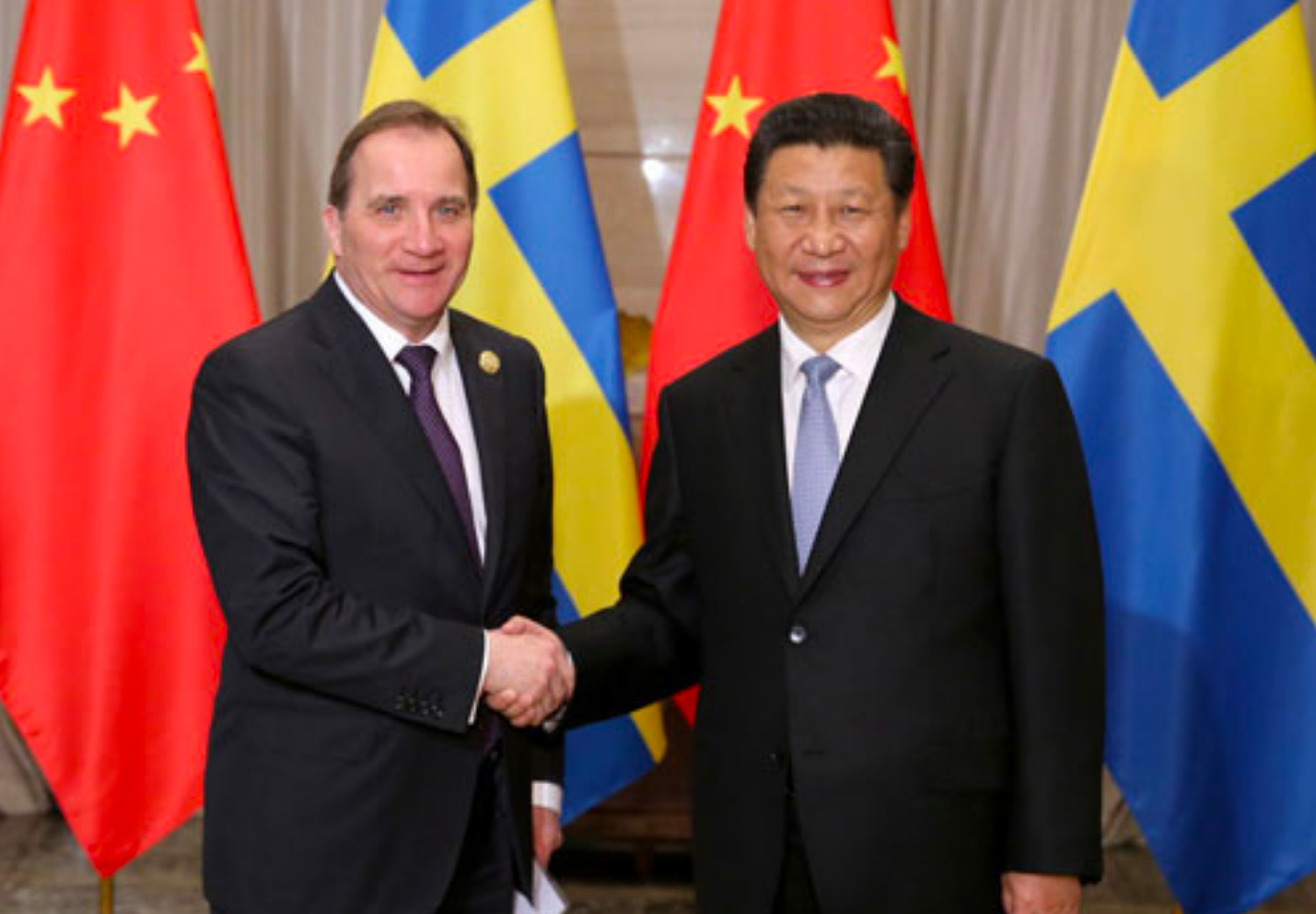

President Xi Jinping and Prime Minister Stefan Lofven of Sweden © fmprc.gov

The Nordic model is essentially a method of governance adopted by what are known as the Nordic countries in Europe : Sweden, Norway, Denmark, Finland and Iceland.

Naturally, the outcomes are not identical in all these countries but generally speaking, it has yielded good results in terms of growth, employment and competitiveness, but also gender equality, living conditions and open-mindedness.

In a speech at New York University in 2014, Stefan Löfven said : ‘Sweden has made a moral choice : to give every individual the chance to succeed in life. We will create a common society, which means that our common support must be the strongest when the individual needs it the most…this is perhaps the most crucial and basic explanation of the Nordic model.‘

Since 2014 and the premiership of Stefan Löfven, the Swedish government is made up of an equal number of men and women. This aimed to put into focus the concept of gender equality both at home and abroad.

It is in fact, the world’s first feminist government.

The policy of gender equality and of a feminist government aims at providing conditions for men and women to develop without obstacles, prejudices and stereotypes.

But of course, the main pillars of this model remain firstly, an economic policy focused on full employment ; secondly, a universal and generous welfare system and thirdly, a well- organised labour market.

MAKING HEADWAY IN FOREIGN POLICY

President Donald J. Trump and Swedish Prime Minister Stefan Löfven participate in a joint press conference in the East Room at the White House, in 2018 © Stephanie Chasez

From the outset, in the area of foreign policy, Stefan Löfven hasmade moves that some have qualified as courageous and others as reckless.

As far back as October 2014 on the day of his inauguration as Prime Minister and in his Policy Statement to the Swedish Parliament, he announced that his government would officially recognise the State of Palestine.

This decision which was made by Löfven’s government without formally consulting its allies heralded a wider policy shift that had at its heart the aim of asserting a new diplomatic weight around the world. The speed of their post-election announcement surprised a number of countries, including of course Israel.

Until then and under a centre right government, Sweden had been close to Washington, active in Western military operations and a vocal proponent of EU market reform.

In making it the first major European country to recognise the Palestinian state, Sweden’s new centre left government looked like it was suggesting a change of direction on several of those fronts.

Prime Minister of Sweden Stefan Löfven and French President Emannuel Macron © se.ambafrance.org

In 2014, shortly after Stefan Löfven’s government began work, Sweden became the first country in the world to formulate and pursue a feminist foreign policy. This policy which was launched by the then Swedish Foreign Minister, Margot Wallström was hailed by some as progressive and dismissed by others as provocative.

Feminist foreign policy is based on the notion that more women means more peace ; that it’s a matter of involving and engaging women in peace processes and that this is good for both peace and security in every country.

At a meeting at the UN Security Council in 2017, Wallström said : “Throughout the world, women are neglected in terms of resources, representation and rights. This is the simple reason why we are pursuing a feminist foreign policy – with full force, around the world.”

The policies in question include among other initiatives, efforts to educate women in Saudi Arabia and Iran – not without controversy – to enhance their economic empowerment, initiating a public debate in Rwanda about the role of fathers, working to stop female genital mutilation, and funding international projects in the area of sexual and reproductive health and rights.

Minister of Foreign Affairs of Sweden Margot Wallström the day after the terrorist attack in Stockholm in april 2017 © Frankie Fouganthin/Wikicommons

Stefan Löfven himself has been at the forefront of sustained initiatives in the field of Swedish foreign policy, with visits to many countries on all continents in view of contributing to the creation of peace and security through preventive measures, peace diplomacy and stable bilateral relations.

The Swedish government is also developing partnerships on a broad front – in the EU, the Nordic and Baltic regions, the UN and the OSCE as well as NATO and other partners.

As far as NATO is concerned, Stefan Löfven has stated that Sweden will not apply for NATO membership. In a recent interview, he said : “ This is not a smart thing to do. We are convinced that we won’t have a safer Europe if you move the frontiers of NATO to touch those of Russia. Sweden and Finland today act as buffer zones and it is safer for Sweden and Finland, as well as for Europe.”

So, Sweden will continue its policy of military non-alignement but will remain an active partner of NATO in a number of important cooperation programmes worldwide.

Sweden is also actively pursuing concrete initiatives for global nuclear disarmament.

In December 2019, in what was the first ever address by a Swedish leader to the South Korean parliament Stefan Löfven vowed to continue cooperative efforts to achieve lasting peace on the Korean Peninsula.

Pointing to the North Korean nuclear issue, he highlighted the need for joint efforts to tackle the problem and promised such efforts from the Swedish government.

In his push towards more international cooperation, Löfven visited Iran in 2017 and held talks with Ali Khamenei in view of improving economic relations.

President of the Islamic Republic of Iran Hassan Rouhani and Prime Minister of Sweden Stefan Löfven © president.ir

He also travelled to India, where he led a large delegation to the Mumbai Summit in 2016, before welcoming Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi to Stockholm in 2018. The two leaders signed agreements to strengthen defence and security cooperation and held talks to chart out a future roadmap of cooperation in sectors such as trade and investment, science and technology, clean energy and smart cities.

Sweden and the United States have strong economic ties with the US as the third largest Swedish export trade partner.

American companies are the most represented foreign companies in Sweden.

The Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) which is under negotiation between the EU and the United States is a deal that aims to promote trade and economic growth and it is expected to be the biggest trade agreement ever negotiated.

For Löfven, this deal is extremely important for Sweden but he has insisted that some sort of mechanism be implemented that will not be detrimental to social conditions and would guarantee human rights.

Stefan Löven during a “summer speech” in Stockholm © Jonatan Svensson Glad /Wikimedia Commons

The next general elections in Sweden are due to be held in September 2022 and Stefan Löfven and his Social Democrats will again confront their old political rivals.

But with each passing year and the profound transformation of Swedish society in the last ten years, it has become slightly more difficult to predict the exact nature of the future governance of that country.

Sweden isn’t by any measure the most extreme example of an anti-immigrant backlash. Across Europe, the United States, Russia and the rest of the world, there are much more alarming nationalist and nativist uprisings.

But when even a small minority in one of the most welcoming and tolerant societies starts tapping into an undercurrent of resentment and fear of the ‘other’, some suggest it can trigger a tectonic shift with unpredictable consequences that can take generations to restore.

Hossein Sadre

Click here to read the 2020 June edition of Europe Diplomatic Magazine