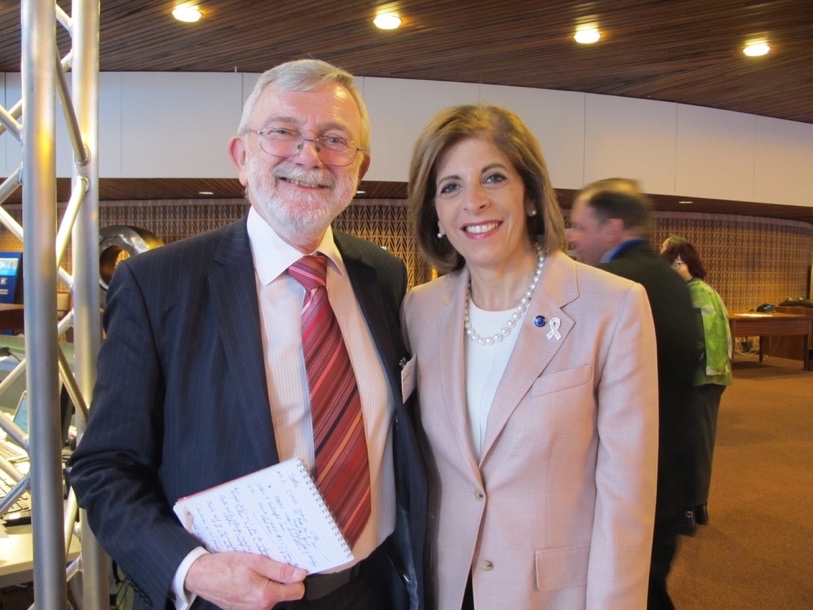

It cannot be easy to become the European Union’s Commissioner for Health and Food Safety just before Europe is struck by the worst pandemic in recent history. It would be like being appointed captain of the Titanic just before someone notices that big lump of ice floating in the sea ahead of you. There is an inevitable consequence of something monstrous arising out of nowhere and causing massive, deadly damage: panic. Stella Kyriakides didn’t panic but a lot of people who should have known better did. Some of them are still doing so. When I interviewed her in Strasbourg in late January, 2020, she was looking forward to getting to grips with the EU’s new cancer campaign. Being a survivor of breast cancer, she attached a lot of importance to it: it was the cause of her mother’s death, at a time when the word ‘cancer’ was generally not mentioned, as if the condition was somehow shameful. As she told the website CancerWorld, “My mother and father were well-known people in what is still a small community, and she never tried to hide her condition,” she says. “Right to the end of her life – and she lived with breast cancer for 10 years – she attended functions and got on with things. She was certainly, unknowingly, one of the first breast cancer advocates in Cyprus.” When I spoke with her, Kyriakides was looking ahead to Tuesday, 4 February, World Cancer Day, on which day she was scheduled to launch the consultation phase of a new project, called simply ‘Europe Beating Cancer’, which she hoped to roll out by the end of 2020. The coronavirus got in the way.

Her enthusiasm for the planned project was very much on view. “This will aim to look at the whole journey of the cancer patient and really address the problem faced by member states and hoping we’ll be able to join the dots to help look at all the aspects.” Hearing her, it was clear that this would be a campaign she would really get behind. “This Commission is very committed to this. It is one of the key priorities and it is in my Commission letter from President von der Leyen. So I really have the opportunity now to work at the European level to change the face of this disease.” The President’s letter, written long before the Covid-19 pandemic began, is very prescriptive: “I want you to look at ways to help ensure Europe has the supply of affordable medicines to meet its needs. In doing so, you should support the European pharmaceutical industry to ensure that it remains an innovator and world leader. I want you to focus on the effective implementation of the new regulatory framework on medical devices to protect patients and ensure it addresses new and emerging challenges.” In one part, it reads almost like a premonition: “Many of today’s epidemics are linked to the rise or return of highly infectious diseases,” the President wrote, more perceptively than she knew, “I want you to focus on the full implementation of the European One Health Action Plan against Antimicrobial Resistance and work with our international partners to advocate for a global agreement on the use of and access to antimicrobials.

I want you to prioritise communication on vaccination, explaining the benefits and combating the myths, misconceptions and scepticism that surround the issue.” That’s a problem Kyriakides will have to deal with in the future, once an effective coronavirus vaccine has been found: dealing with the ‘anti-vaxers’, the conspiracy theorists who think it’s all part of a plan to turn us into obedient robots and other such anti-scientific nonsense.

During her eight years as a member of the Council of Europe’s Parliamentary Assembly, she had already become involved in cancer-related campaigning.

As the Assembly’s 30th President, she was already the first Cypriot national and only the third woman to hold the post, and during her time there she took up the issue of breast cancer. “I wanted to share with you that I was privileged in the Parliamentary Assembly: we started a yearly event every October to highlight awareness about breast cancer, and I think we can do a lot more to raise awareness about cancer at the European level.” I’ve no doubt she still can, although the Covid-19 pandemic has derailed plans of every type in every country. She was in Strasbourg in January to receive an honorary diploma for her work there in the past and she clearly still has many friends in the Assembly. She is also up-to-date on international issues of constitutional matters, having served as the Assembly’s representative to the Venice Commission, the Council of Europe’s independent consultative body on issues of constitutional law, including the functioning of democratic institutions and fundamental rights, electoral law and constitutional justice, which meets four times a year in an ancient Venice palazzo.

Health issues are of great importance to Kyriakides. In her first public address after being appointed as Commissioner for Health and Food Safety, she said: “I know from my own experience the importance of well-functioning health systems that provide equal access to all citizens.

Access to the appropriate health services is a fundamental right, not a luxury, for all European citizens.” Born in Nicosia, she obtained a degree in Psychology from the University of Reading in the United Kingdom, going on to get a Master’s Degree in Child Maladjustment at Manchester, completing her dissertation shortly after her mother’s death. She is married with two sons. From 1976 she worked for ten years as a clinical psychologist at the Ministry of Health, Cyprus, in the department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, during which time she was appointed President of the European Breast Cancer Coalition, Europa Donna. In 2016 she was appointed President of the National Committee on Cancer Strategy of the Council. “As many know, I myself have been diagnosed with cancer, so I know what it’s like,” she told me, “especially that word, when suddenly everything else is blacked out for the first five minutes at least, and more. It is a terrifying word but you need to look at the positive and we need to look at what we can do for prevention, and we need to look at how we have improved survival rates over the last twenty years.” It’s very hard to look on the bright side after being told one has cancer, of course, and a great deal needs to be done to make it seem less of a possible death sentence. “There are inequalities across member states and this is what we need to address,” she says. “We need to use innovation, we need to use digitalisation to improve cancer care and I’m hopeful that with research there will come a day when the word ‘cancer’ will still bring a lot of emotion, but it will also bring the sense of hope, which I think it brings today for a lot of the types of cancer that we are able to address.”

THE LABOURS OF HERCULES

Cancer, of course, remains a terrifying diagnosis to receive, and it’s not a disease that is easy to deal with, coming in many forms, some much more serious than others.

It is more akin to the Lernean Hydra of Greek mythology, the monster with nine heads (the number varies from source to source, some giving the number as fifty or even a hundred, according to my ancient Lemprière’s Classical Dictionary).

It was difficult to defeat because every time a head was chopped off, two more grew from the scars. It took Hercules to defeat it, with the help of Iolaus and a hot cauterising iron for the neck from which Hercules removed each head. Fortunately, the Hydra is a mythical beast; unfortunately, cancer is not, of course. Commissioner Kyriakides acknowledges the multi-source problem. “It affects people in different ways. It’s not a single disease.” Not only that, but it has many causes, too.

In that and many other ways, it is totally different from the current crisis over Covid-19, whose single cause is the SARS-Cov-2 virus. The virus’s strangeness and potency are underlined in a special report, published in the June 2020 edition of Scientific American: “This coronavirus is unprecedented in the combination of its easy transmissibility, a range of symptoms going from none at all to deadly, and the extent that it has disrupted the world. A highly susceptible population led to near exponential growth in cases.” What is needed is a vaccine and attempts to create one are going on all over the world. It’s worth remembering, though, that even though the development of a vaccine for Ebola was fast-tracked, it took five years for it even to reach the stage of widespread trials. This is not the sort of news that is likely to be welcomed by a Commissioner for Health and Food Safety. We just have to hope that the various approaches, using fragments of a weakened or dead virus or isolated parts of it, or through genetically engineering virus genes, will prove effective more quickly. As Kyriakides said, “We will work hard to make a difference, to give European citizens everything they expect from us in the area of health.”

What the citizens expect and what their leaders will accept are not necessarily the same thing. All EU member states want more money to help them cope with the disaster, for one thing, so they welcomed the EU’s health programme, called EU4Health when it was announced in May, 2020, and gave a very big welcome to the increase in its budget from €413-billion, the figure set in 2018, to its new pandemic-countering figure of €9.4-billion. “We are stepping up to these challenges,” Kyriakides told a media briefing, “With an over-2,000% budget increase, compared to current resources for health. This will allow us to face the challenges brought to light by the crisis but also, importantly, to invest in the EU health systems for the future.”

The leaders even gave the Commission the authorisation to buy vaccines for them, when they are eventually developed, tested and released. The Commission has agreed to spend more than €2-billion on advance purchasing agreements of likely vaccines while they’re being tested. But member states also flagged up their desire to retain control over the programme. Roland Driece, Director of International Affairs at the Dutch Health Ministry, was quoted on the Politico website as saying “It’s important to keep member states in the driving seat,” which suggests that they may be putting sovereignty above efficacy. “The proposed rôle of member states in the execution of the programme seems too limited.” It’s a fear that seems to be fairly widely shared, notwithstanding Kyriakides wish to do whatever it takes for the health of Europeans. She insists that the fears are groundless. “Member states will be involved at many different levels and programme objectives,” she said, adding that they will also be setting the agenda. The sometimes nationalist sentiments expressed by some member state politicians may see strange in the midst of a pandemic, but as a clinical psychologist, Kyriakides should be able to understand. As for the “me first” attitudes of some leaders, she also has her training in understanding Child Maladjustment to fall back on. It could come in useful.

She admits that there remains a “gap between what citizens have expected and what the EU could do in terms of health.” So, Kyriakides still has hills to climb and battles to fight, but at least there was agreement to let the Commission go ahead and acquire the vaccines, if and when they become available. There has also been a call, welcomed by Kyriakides, for the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control to take on more responsibility, including the creation of a rapid reaction force of experts. “We have an opportunity,” Kyriakides said. “Let’s not waste it.” She dismisses claims that the EU was slow to act over the Covid-19 crisis; it was the member states which seemed to react like rabbits caught in the headlights of a speeding car (my phrase, not hers). The EU tried to co-ordinate but, as so often before, the member states were suspicious of Commission motives at a time when no-one could afford suspicion. The Commission did its best, Kyriakides told the Irish Times: “We offered to help with procurement of PPE [personal protective equipment] in January, but it was not taken up. Possibly at that point in time, member states could not foresee the scale and the speed at which this was going to spread.” They were to learn the dreadful truth all too soon.

IF YOU ARE WHAT YOU EAT, EAT HEALTHILY

The problem with being the Commissioner for Health and Food Safety is that coronavirus looms so large in the popular imagination and dominates the media to the extent that it’s easy to forget food safety. We shouldn’t. Some governments, especially those that lean towards the more authoritarian right, have even called for such initiatives as the Green Deal and the Farm to Fork Strategy to be abandoned because of the pandemic. Kyriakides argues that this is just the time when it’s most important. At a time of crisis, after all, people still need to eat and – especially now – to eat well. And, as she pointed out at the launch of the Farm to Fork initiative, coronavirus is not the only crisis to hit Europe; we’ve also had droughts, floods and forest fires to contend with. “Food systems are the key drivers of climate change and environmental degradation,” she reminded the media. “In the EU, agriculture is responsible for over 10.3% of the greenhouse gas emissions. The Farm to Fork Strategy is thus critical to delivering the European Green Deal. This is why sustainability needs to be seen as a growth strategy. It is an opportunity for Europe’s farmers, fisher-men and -women and food producers to become global leaders in sustainability and to guarantee the future of the EU food chain.” If you tend to think that it is a matter of minor importance in the light of the Covid-19 pandemic, think again. “The transformation of our food production system has, as we all know, been at the top of the agenda since the President’s ‘political guidelines’ [were published] in July, but the Covid-19 pandemic has brought into sharper focus the importance of having a resilient food system and food security, given the strong links between health, the eco-system and supply chains.” In other words, if we really are what we eat, we need to ensure we’re eating healthily, especially at the moment.

That also means ensuring that our farm animals are well fed. When she was first appointed to her current rôle, she said she wanted to see the EU lead by example, working together to challenge misinformation directly impacting on human health. She mentioned new regulations on veterinary feed and medicines, calling it “almost a cornerstone of AMR” (Anti-Microbial Resistance), and reviewing regulations on where antibiotics cannot be used to assess if they are being implemented effectively. “Member States need Europe to act,” she said, “national solutions are not enough.” Under the Farm to Fork Strategy, the European Commission has set targets to reduce pesticide use and sales of antimicrobials by 2030. The strategy includes a 50% reduction in the use of pesticides and antibiotics used in animal husbandry and other agricultural products, as well as a 20% reduction in the use of fertilisers and a regulation that 25% of all farm land should be used for organic farming.

It will also lead to a clampdown on food fraud. When the plan was debated at the European Parliament’s Committee on the Environment, Public Health and Food Strategy, there was a concern raised by Norbert Lins, who chairs the Parliament’s Agriculture Committee: “The Farm to Fork strategy can only be successful if there is a balance between the farm and the fork,” Lins said. “The conspicuous absence of the Agriculture Commissioner (Janusz Wojciechowski) at [the] Commission press conference does not give us much hope that the strategy aims for such a balance. We need to give our farmers the respect and support they deserve for filling our tables every single day and not to overburden them with disproportionate requirements.” This was reported in Food Safety News, but it should be pointed out that other MEPs attending seemed largely supportive of the plans. Many of them are suspicious of farmers, probably unfairly, in the wake of such episodes as the substitution of horsemeat for beef in some products and the mad cow disease scare, bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE), which seems to have been blamed on the food given to farm animals, containing ground up meat polluted with prions from scrapie-infected sheep. But there was a warning from Tim Cullinan, President of the Irish Farmers Association: “It is not credible for the EU to drive up production costs for European farmers while at the same time looking for low food prices,” he told Food Safety News.

“They want food produced to organic standards, but available at conventional prices. It is likely that farmers will end up paying through higher costs and low prices while retailers will continue to make billions.” Of course, the villain of the piece here as far as most farmers (and many MEPs) are concerned is the food retail industry, especially the all-powerful supermarkets, which force farmers to sell their milk at below cost price.

DRUGS SCARCITY

Ensuring healthier food through the Farm to Fork Strategy is one part of the move towards a healthier population, but world attention remains focused on the coronavirus and the Covid-19 pandemic. That’s why Kyriakides has been in negotiation with the pharmaceutical company, Gilead, that produces the drug Remdesivir. No-one is talking about what progress she may be making at present, after the United States ordered half a million doses for exclusive US use. That equates to the total production of July and most of the company’s August and September production. Remdesivir is not a cure but it can alleviate symptoms in the severely ill and save lives. At the time of writing, no-one can say if the Commission’s purchasing power can have an impact on the producer. Commission spokesperson Stefan de Keersmaecker told journalists that the talks are confidential.

Meanwhile, the EU4Health strategy is designed to make the best use of existing resources, while having more to spend. “Our first objective needs to be,” Kyriakides told the media, “to be better prepared to react and to protect our citizens, should a similar cross-border threat and crisis hit us in the future. To do so, we will aim to ensure that we have at all times the means and the necessary personal protective equipment (PPE), medicines, medical devices available and to ensure they are affordable and innovative. Never again do we want to see our healthcare workers having to choose which patient receives life-saving equipment.” She talked of creating a ‘strategic stockpile’ to enable the EU to plan ahead and also to have reserves in hand in case of crises.

It’s somewhat ironic that it was in April this year, just as the true horror of the Covid-19 outbreak was becoming clear, that World Health Day occurred. Not surprisingly, under the worsening conditions of the time, Kyriakides took the opportunity to give a political message. She thanked the EU’s 1.9-million doctors and 4.1-million healthcare assistants, reassuring them that the European Commission was doing its best on their behalf. “It is important that you, our healthcare workers, be protected from the risk of infection,” she told them.

“By launching the EU joint procurements, we are supporting Member States in gaining access to more personal protective equipment for hand, body, eye and respiratory protection. As an additional safety net, we have proposed creating a rescEU stockpile, a common European reserve of personal protective equipment and reusable masks. In order to ramp up production of such equipment, we have adopted decisions on revised harmonised standards. This will help companies to manufacture the items without compromising on our health and safety standards, and especially without undue delays.”

While Kyriakides has welcomed the success of lockdowns and other measures, she admitted to the European Parliament’s Environment, Public Health and Food Strategy committee that it’s too early to take much comfort. “This is the sort of crisis that none of us have had to deal with before,” she said. “What is also clear is that Coronavirus will not be going away. We have got to learn to live with it until a vaccine is found. I must stress this.” In the meantime, EU countries must remain co-operative – more so than when the virus first appeared – and work together. “We all now agree that a coordinated approach is essential. However, if we move too quickly on exiting the crisis and fail to communicate with citizens there is a risk of an increase in cases and we will end up wasting the sacrifices made by those on the health frontline and citizens. In terms of the way forward we are now at what I would call an experimental phase but we are still basing our decisions on the latest scientific advice and the capacity of health systems to manage things.”

DON’T TAKE YOUR EYES OFF THE PRIZE

But cancer still remains one of Kyriakides primary concerns. Although her mother died of breast cancer and she herself has been diagnosed with it twice, it’s not the only form of cancer, of course, and nor are women the only victims. In the European Union over 2 million men are living with prostate cancer, the most frequently diagnosed cancer from which men suffer. More women suffer from breast cancer than men from prostate cancer, but more men die from prostate cancer than women from breast cancer. Prostate cancer mortality among men ranks second only to lung cancer, and before colorectal cancer, according to the UroWeb website (other sources suggest that colorectal cancer comes first among cancers amongst men). “Around 450,000 new cases were diagnosed in Europe in 2018, compared to an estimated 345,000 in 2012,” it reports. “Each year, prostate cancer accounts to around 25% of all new cancers and 10% of male cancer deaths, with over 107,000 people estimated to have died from the disease in 2018.” You get the feeling that, for Kyriakides, the Covid-19 pandemic is an unwanted distraction, obliging her to take her eyes off the prize of really getting to grips with cancer. It remains a massive problem. According to the European Journal of Cancer (EJC): “Europe contains 9% of the world population but has a 25% share of the global cancer burden. Up-to-date cancer statistics in Europe are key to cancer planning.” The statistics are deeply worrying and, unlike SARS-Cov-2, the answer is unlikely to lie in a single vaccine, however hard to discover. “There were an estimated 3.91 million new cases of cancer (excluding non-melanoma skin cancer) and 1.93 million deaths from cancer in Europe in 2018,” reports the EJC. “The most common cancer sites were cancers of the female breast (523,000 cases), followed by colorectal (500,000), lung (470,000) and prostate cancer (450,000). These four cancers represent half of the overall burden of cancer in Europe. The most common causes of death from cancer were cancers of the lung (388,000 deaths), colorectal (243,000), breast (138,000) and pancreatic cancer (128,000). In the EU-28 (this was published, of course, before the UK’s controversial departure reduced the EU-28 to 27), the estimated number of new cases of cancer was approximately 1.6 million in males and 1.4 million in females, with 790,000 men and 620,000 women dying from the disease in the same year.”

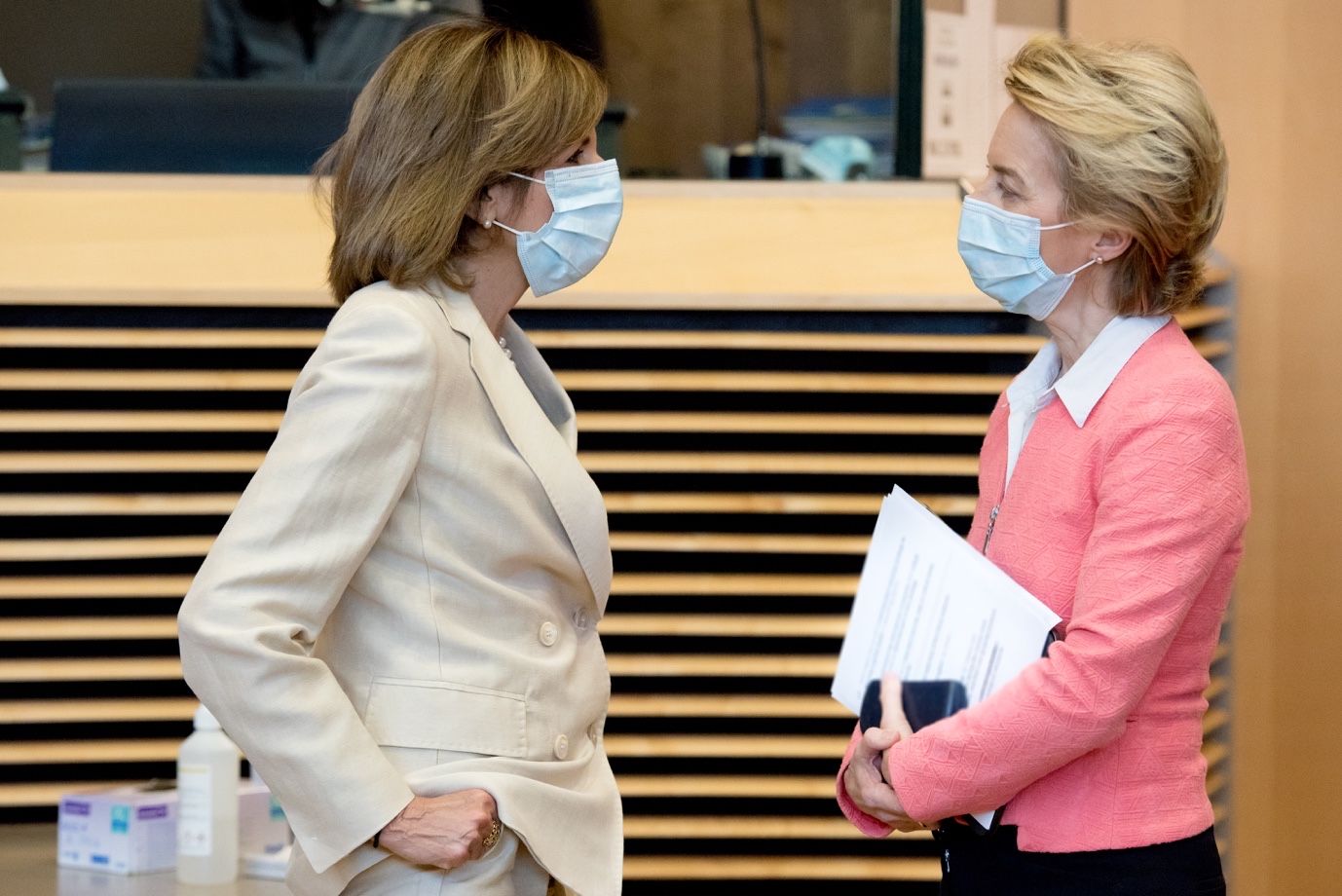

That was why Kyriakides joined European Parliament First Vice-President Mairead McGuinness on 4 February, World Cancer Day, where together they greeted a choir made up of cancer survivors, who sang to give hope and encouragement to those still suffering. Finding a way to defeat cancer remains her priority. It’s a complex complaint, as the World Health Organisation (WHO) explains. “Cancer is the uncontrolled growth and spread of cells that arises from a change in one single cell,” Why does that happen? The WHO again: “The change may be started by external agents and/or inherited genetic factors and can affect almost any part of the body. The transformation from a normal cell into a tumour cell is a multistage process where growths often invade surrounding tissue and can metastasize to distant sites. These changes result from the interaction between a person’s genetic factors and any of 3 categories of external agents: physical carcinogens, such as ultraviolet and ionizing radiation or asbestos; chemical carcinogens, such as vinyl chloride, or betnapthylamine (both rated by the International Agency for Research into Cancer as carcinogenic), components of tobacco smoke, aflatoxin (a food contaminant) and arsenic (a drinking-water contaminant); and biological carcinogens, such as infections from certain viruses, bacteria or parasites.” We can’t avoid contact with all of those things but we can adopt simple measures to minimise the risk. And cancer need not be a death sentence. “Many cancers can be prevented by avoiding exposure to common risk factors, such as tobacco smoke,” says the WHO. “In addition, a significant proportion of cancers can be cured, by surgery, radiotherapy or chemotherapy, especially if they are detected early.”

It’s a crusade, and one in which Kyriakides hoped to play a leading rôle before the coronavirus got in the way, but the battle goes on. “Research is expensive,” she told me, “but there is a commitment by the Commission and it is a priority, so we need to look at all the aspects. We are not in a position now to say what needs to be done. We need to be able to know where the gaps are. But by the end of 2020, we hope we will have a plan.” That fine ambition may have taken a knock in terms of a timetable in the light of the pandemic, but Kyriakides is determined to continue the war of cancer that has occupied much of her professional life, including at the Council of Europe Parliamentary Assembly. Could the European Commission and the Assembly work together on it, I asked her, as she had such intimate experience of both? “Of course, they’re totally different,” she told me, “and I think they have a different way of working. But I believe that cooperation is always possible and we need to be aware of the work being done, both at European Union level but also at the Council of Europe level to see where we can work more closely together.”

What more could be achieved by the two organisations cooperating on battling cancer is hard to assess. As Kyriakides said, they are very different and work in very different ways. But that doesn’t mean there aren’t gains to be had by acting together. Cancer being such a multi-source condition with so many possible causes, it may never be possible to defeat it entirely. But to render it less harmful, less fearful, less of a life sentence – or even a death sentence – would be one achievement Kyriakides would love to be able to win.

Jim Gibbons

Click here to read the 2020 July edition of Europe Diplomatic Magazine