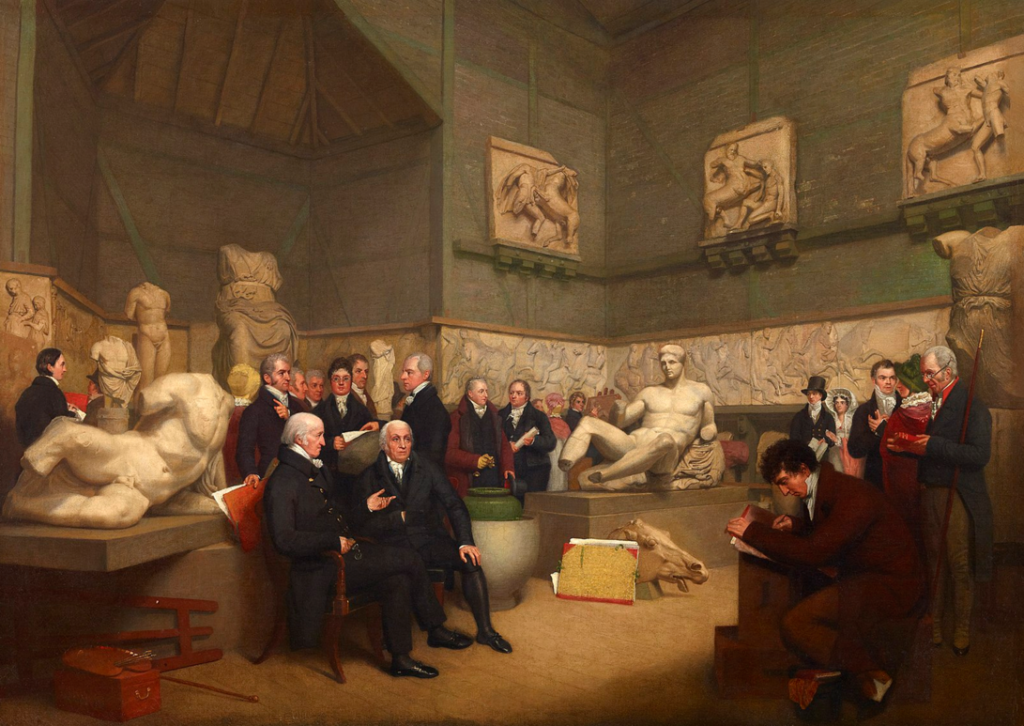

Figures of three goddesses from the east pediment of the Parthenon © British Museum

There is claimed to be an old Indian saying: “A thief is a thief, whether he steals a diamond or a cucumber”. It’s very true, of course, but people take less notice when a cucumber goes missing, while a person who steals cucumbers tends to be regarded rather more leniently by the police and the courts than someone who goes after diamonds. In terms of the scale of thefts, few come close to the British Museum. Its many glorious exhibits and precious artifacts were largely taken dishonestly from their rightful owners by an empire that nevertheless claimed some kind of moral superiority. Not surprisingly, several of the countries from which these goodies were stolen back in those “glorious” days of empire now want them back, and who can blame them? Perhaps the most viciously worded article has been in the the Global Times, which is owned by the Chinese Communist Party’s flagship newspaper, the People’s Daily. In an editorial, it accuses the British authorities of “stubborn and evasive” behaviour. “The UK has a bloody, ugly and shameful colonial history,” it writes, “has always had a strong sense of moral superiority over others, often standing on the moral high ground to dictate to and even interfere in the internal affairs of other countries.” It then adds this killer line: “We really do not know where their sense of moral superiority comes from.” When you put it like that, neither do I.

In an additional irony, the Museum has now admitted to having lost some of its precious exhibits in a series of thefts. And not a cucumber among them! The Museum itself has been remarkably quiet about what is, in reality, a shocking example of careless disregard for other countries’ cultural heritage. One senior curator was sacked after something approaching 2,000 artifacts, together worth millions of euros, were believed to have been stolen. The Metropolitan Police said in a statement: “We have worked closely with the British Museum and will continue to do so,” adding the enigmatic line: “We will not be providing any further information at this time.” This doesn’t really provide much in the way of solace to those countries whose historical items were (they thought) safely stored there, not on their home soil of course but at least where everyone knew their location and might manage to visit them one day. The tight-lipped museum has not specified how many items were taken, nor has it identified exactly what they are, other than to claim that they were “small items” and that they included “gold jewellery and gems of semi-precious stones and glass dating from the 15th century BC to the 19th century AD.” No vegetables were mentioned.

Some of the missing items have been recovered (very few, in fact), but many people think the Museum should have acted more swiftly when some of the stolen items turned up for sale on E-Bay. They had been warned in 2021 (and possibly earlier) about certain items appearing for sale on-line, but the Museum authorities did nothing. In fact, according to some Museum staff, many of the missing items were not on public display anyway: around 99%, it’s thought, were kept in the Museum’s private archives, and there have long been calls for their safe return to their countries of origin. Who had the pleasure of gazing upon them? That’s not clear, other than to say it didn’t include the true owners of the items. The Chair of the Museum’s trustees, former Chancellor of the Exchequer George Osborne, has admitted that the Museum does not have a comprehensive catalogue of all the items in its vast collection, which is hampering the recovery of those artifacts that are currently missing. It’s a matter of global concern because the collection is so vast, having come from many places all over the world. This is not just a British tragedy, it’s a global one. All in all, the British Museum is where some 8-million objects are housed, almost all of them looted by previous generations of British soldiers, historians and ‘get-rich-quick’ enthusiasts.

| TO THE VICTOR THE SPOILS (AND THE EVERLASTING SHAME)

Of course, Britain is not the only imperialist power to have stolen objects from the countries it conquered. Belgium’s King Leopold was especially brutal towards the Congolese, housing some of them in a kind of “human zoo” in central Brussels, bearing notices instructing people not to feed the exhibits. Other countries carried out similar atrocities, while no doubt claiming to be guided by the morals of their religious faiths. Presumably they could see nothing wrong or morally dubious about their activities. The British Museum itself houses a very large number of items stolen in the distant past, including India’s Amaravati Marbles, the Benin Bronzes from Nigeria and Egypt’s Rosetta Stone, not forgetting Greece’s famous Parthenon Marbles (nowadays generally referred to as the “Elgin Marbles”) and lots of other things that should be on show in the places from which they came. Demands for that to happen have been increasing. After all, their present location is the result of colonialism. Or ‘theft’, if you prefer.

France’s President Emmanuel Macron commissioned a report by art historian Bénédicte Savoy and Senegalese economist Felwine Sarr in 2018 to look into the issue of restitution, and they concluded that “any objects taken by force or presumed to be acquired through inequitable conditions” should be returned to their country or countries of origin. Similar recommendations made to the British Museum have been ignored because the British Museum Act of 1963 prevents it from returning anything in the collection, even though the law permits it to return any object it considers “unfit to be retained in the collections of the Museum.” An object’s arrival in the UK as a result of an officially-sanctioned act of theft apparently doesn’t count.

At the time of writing, Sir Mark Jones has replaced Hartwig Fischer as the Museum’s Director, although that decision still had to be rubber-stamped by the Prime Minister at the time of writing. When he was running the Victoria and Albert Museum, Sir Mark advocated “sharing” the Elgin Marbles with Greece, but Athens has repeatedly declined the offer, stating – not unreasonably – that the Marbles are part of Greek history and that if they are to be put on display it should be there.

They are known as the “Elgin Marbles” because it was Lord Elgin who, between 1801 and 1805, stripped them from their original position and moved them to Britain. Sir Mark has received universal acceptance as Director, according to George Osborne. The British Museum, in an on-line announcement, said: “An independent review will be led by former trustee Sir Nigel Boardman, and Lucy D’Orsi, Chief Constable of the British Transport Police. They will look into the matter and provide recommendations regarding future security arrangements at the Museum. They will also kickstart – and support – a vigorous programme to recover the missing items.” It’s highly likely that most, if not quite all of the missing items will be irrecoverable, having been sold on the international market as artifacts in – I was going to write “good faith”, but that would not be appropriate; if you’re wandering the antique shops and somebody offers you a rare item at a knock-down price but with dubious provenance, you’re bound to know it’s stolen. In British slang, you’d say the item is “hot”, which presumably is not a description that would ever suit a cucumber. Who would want a ‘hot’ cucumber?

Sir Mark’s views on “sharing” the treasures chime with those held by Osborne, who has been holding talks with Kyriakos Mitsotakis, the Greek prime minister, over a “Parthenon partnership”. That could result, if successfully worked through, in some of the sculptures being displayed in Athens while never-before-seen treasures are lent to the British Museum in return. There were rumours that Osborne and Fischer did not see eye-to-eye about the marbles and since it was Britain that took the cucumber, and is therefore a thief under the old Indian definition, it would appear that Athens has a strong argument on its side. Don’t expect an early resolution to the dilemma.

| STEALING HISTORY AND HERITAGE

The so-called “Elgin Marbles” may be seen as centre-stage in this dispute because of their worldwide fame, but they’re far from being the only items at issue. Take, for example, Ghana’s Akan Drum. According to Ernest Domfeh, a present day Ghanaian drummer and dancer, it was made when Prempeh 1 was King of the Ashanti (1888 to 1931) and was thus the 13th ruler of the Ashanti people. Britain deposed him and deported him to Sierra Leone in 1897 because the British saw the Ashanti peoples as powerful and therefore a potential danger to British rule. The drum is made of bronze, an Ashanti speciality. Putting scenes into bronze was how the people of the time recorded events and personalities. When the British took the drum (and other bronze artifacts) they stole some of the people’s history. History is important, of course, because it’s part of the identity of the people whose lives and origins it represents. Prempeh’s life was tragic because of Britain. In 1924 he was finally allowed to return to Kumasi and in 1926 was installed as Kumasihene, a simple divisional chief, a much lower and non-royal position. There seems to have begun a movement towards restoring these artifacts to their rightful owners, but it’s a very slow process. It’s also embarrassing for the former colonial power to admit it is in possession of “the priceless cultural patrimony of a formerly colonized continent,” as Howard W. French, a columnist at Foreign Policy put it.

He also points out how the theft of so much cultural art in the past has to do with the continent’s current instability, poverty, and weakness. We Europeans didn’t just steal priceless historical objects, we stole history itself. Apart from the artifacts, of course, we also shipped more than twelve million Africans across the Atlantic in chains, mainly to work on plantations. According to French, only some 42% of those loaded onto slave ships survived to be sold. As the historian Brenda Plummer wrote of the wars in Africa among European powers over the land they had stolen: “These wars featured the theft of indigenous treasures and the first widespread use of machine guns. Mandingo warrior-king Samori Touré lost to France in 1898. German punitive expeditions against the Maji-Maji uprising in Tanganyika from 1905 to 1907 cost 120,000 African lives. In seeming dress rehearsal for the destruction of the European Jews a generation later, German troops in Southwest Africa (now today’s independent Namibia) nearly exterminated the Herero and Hottentot tribes.” It’s also been estimated that the wars promulgated by Belgium’s King Leopold and which helped build Belgium’s wealth also killed ten million Africans.

| SOME OF THE BEST KNOWN CULTURAL ITEMS THAT THE BRITISH EMPIRE HOLDS FROM OTHER COUNTRIES

It was in the interests of the European powers to play down the sophistication of African people and to portray them as backward and “in need of leadership by Europeans” (which means, of course, “leadership by white people). If that attitude on the part of Europe’s colonists hadn’t existed, Africa would be a very different continent today. Take Ghana as an example. In the late 19th century, the Fante ethnic group there formed a confederacy and created a written constitution, with a king-president, a council of kings and elders and even a national assembly. However, Britain, Denmark and the Netherlands had considerable economic interests there and saw the increasingly sophisticated political arrangements as a threat to their profits. The Fante people’s dream of a modern future was deliberately smashed by European powers one might have imagined would have welcomed such a step forward. An attempt in the early years of the 20th century to bring West Africa’s English-speaking colonies together was declined by Britain, despite the plan’s originator, Joseph Ephraim Casely Hayford expressing a willingness for the place to remain part of the British Empire. In a sense it reinforces the belief that the theft of so much of Africa’s cultural art was more about power and control than it was about the market value of the items stolen. We Europeans were thieves of totems, the ideas of a better future and the things that represented those ideas to the public eye.

| GRAB IT AND RUN

Where did this gross greed for other people’s land begin? Of course, the Romans, Phoenicians, Arabs, and Egyptians, among others, had been colonialists, too. It’s hardly a new phenomenon. However, it really caught on in the modern era following the fall of Constantinople to the forces of the Ottoman Empire in 1453, which closed the profitable trade routes to Asia. Several European countries pushed their way into Africa, while the Spanish started taking an interest in the Americas, which took their name in 1503 from the explorer Amerigo Vespucci. The Spanish also took with them the Inquisition, unfortunately. With the demand for sugar came an increased demand for sugar plantations and that meant slavery, of course. In the 16th and 17th centuries, England, France and the Dutch Republic started to build empires overseas, mostly (but not exclusively) in Africa. The colonising states were frequently at war with each other, like gangs of thieves arguing over the loot from a lucrative burglary. Such was the urge to colonise that only thirteen of today’s independent countries escaped such a fate.

According to Deutsche Welle (DW), a few “historic milestones” have been reached in coming to terms with Germany’s colonial history. The news channel quoted German State Minister for Culture Monika Grütters, who listed the return to Namibia of the whip and the Bible of local folk hero Hendrik Witbooi, along with Germany’s commitment to return the so-called Benin bronzes to Nigeria, which should have begun in 2022.

“The matter must and will continue to be a high priority for cultural policy, also and especially here in Germany,” said Grütters at the opening of the conference. Requests for the return of cultural and historic objects in the 19th century were largely declined or ignored, undermining the political authority of the country concerned. Mainly, this colonisation was motivated by the lust for profits, but these dishonourable motives were hidden by a supposed wish to spread Christianity and by the bizarre belief in the fictional Christian kingdom of Prester John, with the aim of encircling parts of the Islamic Ottoman Empire.

The profits to be made from these conquests mainly centred on the spice trade. The colonisation that ensued was largely disastrous for the local peoples the Europeans encountered, either because of their superior weaponry or because of the wide variety of diseases they brought with them, which swiftly spread. The Europeans also showed themselves to be far more ruthless than the local population had ever experienced before. If you think it’s odd that a supposedly religious race could be so brutal, take a look at the Valladolid Controversy (1550-1551), over which fierce arguments raged concerning whether or not the native Indian population possessed souls. If not, then they were not entitled to mankind’s basic rights. One of those who was against giving them rights claimed they were born as “natural slaves”. Throughout this controversy, of course, the Spanish and Portuguese continued to make a lot of money, some of which the Spanish crown used to fund religious wars in Europe. European nations fought against each other, sometimes using attacks by pirates as a weapon. Sir Francis Drake, now held up as an English hero, was one such pirate. But perhaps we should not single him out, when entire governments were devoted to theft and pillage. Vast numbers of items were taken.

There are several problems concerned with returning the stolen items: do we know who created them and where? Who really owns them? How did they end up in European collections? What exactly do they mean in historical and symbolic terms and to whom? It’s clear that in most cases the items must be returned to their owners, if they still exist and can be reliably traced. What’s more, some of the countries to which these artifacts should be returned lack the facilities to display them and to protect them, although following the experience at the British Museum that may seem a rather weak argument. Should the stolen items only be returned to countries that have appropriate facilities to put them on display whilst also protecting them from theft? But if Britain is incapable of protecting the valued items it looted in days gone by, where would be safe? It’s not easy.

| SPONSORED THEFT

Aljazeera writes in an editorial about returning plundered artifacts, but argues that sending the items back to where they started, although necessary, is not enough: “Decolonising the museum has to go far beyond returning plundered artefacts or tinkering with exhibition displays to present a more accurate version of history. The abject dependence of museums on corporate sponsorship and super-wealthy donors is increasingly coming under fire.” The problem, argues Aljazeera, arises with the museums themselves: “These institutions are the public face of the art world, but their trustee boards are stacked with corporate freebooters whose business values are starkly at odds with those of the cultural creatives whose names and works they buy and sell.” The entire world, it sometimes seems, is in the hands of the super-wealthy, whose morality and motives are, at best, doubtful. The article condemns many of the official responses, both of the museum and of collections themselves, and their corporate sponsors, as inadequate.

Does anyone have the definitive answer? Seemingly not, according to Aljazeera. The Museum of Modern Art (MoMa) in New York has been the location for a number of protests and demonstrations. “MoMa director Glenn Lowry has responded to the weekly on-site demonstrations by accusing Strike MoMa (the protest movement behind the protest) of wanting to “disassemble” MoMa and all museums “so they no longer exist”. That is clearly not the aim of Strike MoMa, which has said it wants to see the Museum upholding the values it’s supposed to endorse. There is certainly not, in the US or elsewhere, a call to close all museums, a move that most people would see as counter-productive and certainly not the aim of those wanting to see looted artifacts return home. Popular opinion would seem to favour restoring the looted treasures.

Take the case of the Rosetta Stone, currently on show at the British Museum. It may well be simply too big and heavy to steal. “It’s war spoil,” said Heba Abd al Gewad, an Egyptian Egyptologist, who told VICE World News: “That’s what it is in reality. It has never left Egypt legally…It’s a trophy of empire.” President Macron’s report by Bénédicte Savoy and Senegalese economist Felwine Sarr concluded that: “Any objects taken by force or presumed to be acquired through inequitable conditions” (surely that must mean all of them?) should be returned to their country of origin, with a broad definition of what constitutes force and inequity.” The British Museum has long hidden its inaction behind that 1963 Act of Parliament that forbids it from returning anything. It’s a pretty poor excuse, really, and always was.

That being said, don’t expect an immediate and thoroughgoing response to all these calls for repatriation. It’s a more complicated story than it appears at first sight, and there are those who are totally opposed to it. The arguments will continue, although hopefully no longer about whether or not native people have souls. We must trust that such nonsense is now behind us. People will come up with similar and equally silly arguments that could protect their rights to act wickedly. Still, at least the discussion has begun, although some of the many, many items held by the British Museum before their more recent theft (their arrival at the Museum at all, of course, came about through theft on a grander scale) may never be recovered so that they’re available for return. Whoever holds them now, we must assume, knows that they are stolen property. Oh, well: at least my cucumber is still here.