Technicians inspecting undersea cable ©Wikimedia

Beneath the relentless waves and the vast stretches of our oceans, there exists a vital network of global communication that many might not even be aware of: approximately 1.3 million kilometres of fibre optic cables. These conduits, mostly hidden from view, form the very lifeblood of connectivity between continents. They facilitate nearly all of our international data exchanges, whether it’s the most mundane email or the complex financial transactions that underpin our economies, as well as vital military communications that must remain secret. Yet, for all their importance, these cables remain vulnerable, lying in the dark depths, far from the protective reach of human hands.

The story of undersea communication cables began in 1850 when John Watkins Brett, an English telegraph engineer imagined a world more connected than ever before. Together with his brother Jacob, he founded the English Channel Submarine Telegraph Company that would go on to link England and France through copper wires.

It wasn’t until 1858, after many attempts and failures, not to mention immense financial resources that a transatlantic cable was successfully laid. This connection allowed Queen Victoria to have a very brief conversation with US President James Buchanan, but above all, it served as a proof of an undertaking that would shape the future of global communications.

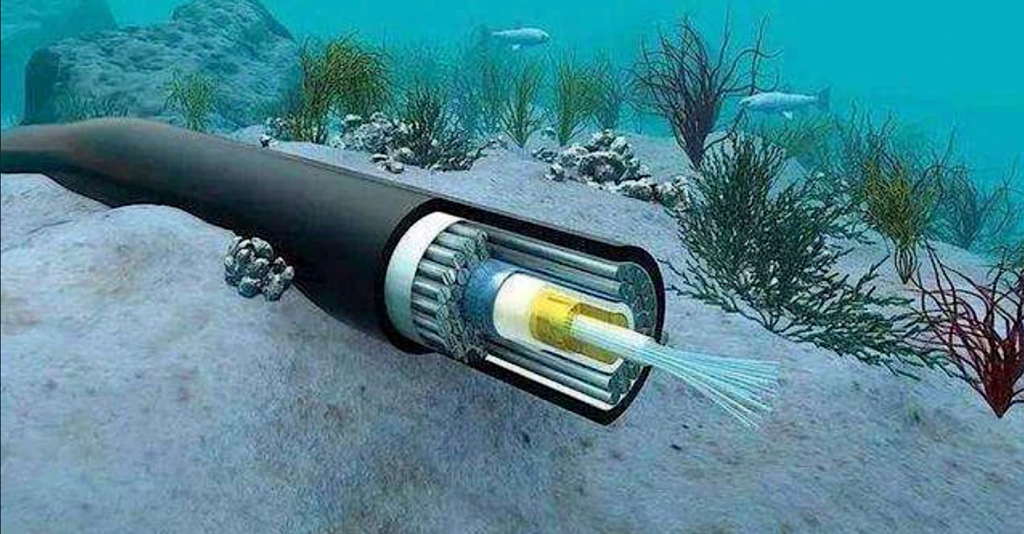

Fast forward to the late 20th century and the advent of fibre optic technology that really changed the game. Made of silica glass threads that send data as pulses of light, fibre optic cables were way better than the old metal cables. They could handle huge amounts of data over long distances without losing signal, which was a big problem with earlier technologies. To make all this happen, scientists had to make some major advances, especially in materials science to create super-pure glass, as well as in lasers and optical physics. This switch to fibre optics not only sped up data transmission but also helped kickstart the global internet age.

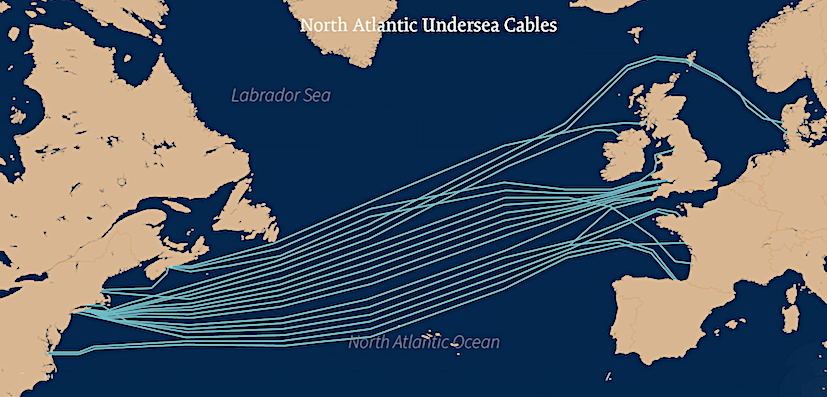

The efficiency of submarine fibre optic cables is undeniable. While satellites were once considered a primary solution for global communication, cables have proven to be both faster and more reliable, allowing for the transmission of 140 terabytes of data per second at nearly the speed of light, on several wavelengths simultaneously. Today, these cables carry up to 97% of international internet traffic.

| GEOPOLITICAL DYNAMICS

Submarine cables might be out of sight, but they are definitely not out of mind in the context of global politics and power. Where they come ashore is not just about what is technically convenient; countries that have these major cable landing points — known technically as cable landing stations or CLS — get a real strategic edge, especially when it comes to data and surveillance. The CLS is where the undersea cable connects to land-based power and various networking provider infrastructure and are therefore incredibly valuable – so much so that nations treat them like critical infrastructure and guard them closely.

The US, the European Union and China, among others, are making huge investments in expanding their cable networks. Their goal? Not just better internet, but a stronger geopolitical position. This has even created a new form of international relations — “cable politics,”— where control of data routes can shift the balance of power.

| THE SUBHALLENGEMERGED ACHILLES HEEL

These cables are like the veins and arteries of the internet, but they are not as tough as one may think. While absolutely essential, undersea cables are surprisingly fragile and face a range of threats, from deliberate sabotage and geopolitical disputes to accidental damage from ships or natural events. That is why redundancy is key; it is like having a backup plan. Multiple cables following the same routes are essential to ensure that a single point of failure doesn’t cripple an entire region’s connectivity.

There exist several modes of attack on the cable infrastructure, the most important of which are scenarios of physical destruction using common, civil vessels such as fishing boats with improvised tools like anchors for easy, low-tech attacks, monitored through maritime surveillance.

Then, there is the use of undersea explosives by deploying military-grade mines or other improvised underwater devices. Although these require some expertise in handling explosives and underwater operations, detection and prevention are challenging.

A third way of carrying out sabotage on the seabed is the utilisation of manned or unmanned submersibles for cutting, damaging or placing explosives and advanced weaponry, which are harder to detect and necessitate sophisticated surveillance.

However, there are a number of other significant vulnerabilities that must be considered for securing these sensitive networks. Attacks can also target cable landing stations (CLS) and maintenance facilities, posing significant risks to connectivity and repair capabilities.

While tapping undersea cables is technically difficult and unlikely, vulnerabilities exist in cable supply chains and onshore facilities, making them more susceptible to data theft and espionage.

Cyber attacks can also exploit remote management systems of cable networks, allowing control over operations and potential disruptions.

Most of these communications cables are predominantly under the ownership of private enterprises, which frequently collaborate with each other. However, some of the organisations engaged in the management of these cables are either state-run or operate under intergovernmental agreements. As a result, submarine cables serve as a significant channel through which companies exert considerable influence on the structure, operation, and security of the global Internet.

Ensuring the safety and integrity of the physical infrastructure that underpins this global network has always been a crucial responsibility for the companies that own and manage them. However, there are three emerging trends that are making the security and resilience of these cables an increasingly urgent concern for the governments of the U.S., the European Union and their allies.

First, authoritarian regimes, particularly in China, are influencing the layout of the internet’s infrastructure. They do this through companies that control key internet assets, aiming to route data in ways that are more advantageous to their interests. This manipulation allows them to gain better control over critical points in the network, which could potentially provide them with opportunities for espionage.

Second, many of the companies managing these undersea cables are adopting advanced network management systems that centralise control over important components in remote operations centers. While this centralisation can improve efficiency, it also introduces new risks to operational security, as it creates more points of vulnerability. Third, the rapid expansion of cloud computing has led to an increase in both the volume and sensitivity of the data that travels through these undersea cables. With more critical information being transferred, the stakes for securing this infrastructure have never been higher.

These trends have complex implications, affecting both geopolitical dynamics and operational practices. While some aspects may be more influential in international relations, others directly impact the day-to-day functioning of network operations. Ultimately, these issues are deeply interconnected, underscoring the need for heightened vigilance and collaboration among all stakeholders involved in managing and protecting this vital infrastructure.

| VULNERABILITIES AND THREAT SCENARIOS

The threat landscape encompasses both state-sponsored and non-state actors, particularly in the context of grey zone warfare, where actions occur below the threshold of armed conflict, complicating attribution and monitoring efforts.

Now, governments are starting to realise just how important these undersea cables are, and they are not taking it lightly. Especially authoritarian regimes. By controlling the companies that build these cables, they can basically reshape the whole internet – both the physical layout and what people can do online. It is a serious power move. According to one report, China has poured over 1 billion dollars into building 27,000 kilometres of cables, managed by dozens of companies, with cable landing stations in many locations, even in the US, South Korea, Taiwan, and Japan. They are clearly playing the long game. (Source: Belfer Center, Harvard Kennedy School, www.belfercenter.org).

Amid growing worries in the US and Europe about Chinese technology making its way into telecommunications networks, subsea cables—responsible for practically all of the global internet traffic—have emerged as the latest potential targets for sabotage. Both China and Russia are being highlighted as primary threats in this scenario. A recent report from the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) shines a light on the vulnerabilities within our subsea cable systems, suggesting a “deliberate” pattern of attacks by China. It is interesting to note that major tech giants like Amazon, Google, Meta, and Microsoft own or lease about half of all the undersea bandwidth used around the globe.

Since 2018, there have been 27 documented cases of Chinese vessels interfering with the undersea cables near Taiwan. One particularly notable incident in 2023 left 14,000 residents completely cut off from digital communication for six weeks, highlighting just how serious and disruptive these actions can be.

| THE SILK ROAD TAKES TO THE DEPTHS

More recently, there has been a real surge in Chinese companies building and owning undersea cables—and these companies, are closely tied to the Chinese government. Take HMN Technologies, for example (formerly Huawei Marine Networks). They already control about 10% of the global market and they have built or repaired almost one quarter of the global undersea cables.

This investment is a huge part of China’s Digital Silk Road project (DSR), which is basically their effort to extend the Belt and Road Initiative into the digital world. And with the tech rivalry heating up, the growth of Chinese tech, and the focus on the Digital Silk Road, it is fairly clear that Chinese leaders are going to keep using these companies to advance their geopolitical goals.

Deciding where, when, and how to build these undersea cables gives the companies involved – and, by extension, the Chinese government – enormous power. They can not only shape how global internet traffic flows, but it also opens the door to things like spying on data and making other countries dependent on their technology. And there is more: the companies that own these cables could easily build in secret backdoors or monitor the cables and landing stations. Even the companies that build the cables could interfere with the security of the whole underwater system. So, as China gains more and more control over this infrastructure, the risk of security breaches and disruptions gets bigger and bigger.

China’s use of sand dredging near Taiwan’s Matsu Islands has been characterised as a form of “grey zone warfare”. Chinese dredgers have been observed operating extensively in the area, removing large quantities of sand for domestic construction. Beyond the direct environmental impact, these activities have reportedly disrupted the local economy, damaged undersea communication cables, and intimidated residents and tourists.

China also possesses the military capability to damage the undersea cable network through sabotage or destruction. However, it is unlikely that such action would occur outside of a context of heightened tensions in the Indo-Pacific region, limiting the immediate threat to European security. Nevertheless, given the EU’s increasing engagement in the Indo-Pacific and concerns about grey zone activities, this potential threat is a growing concern.

| THE RUSSIAN CHALLENGE

Increased control over undersea cable providers by both Beijing and Moscow raises concerns about vulnerabilities and the potential for data interception. The Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI) has reported that Russia is prioritising the targeting of critical infrastructure, including underwater cables and industrial control systems, within the US, the EU and allied nations. This focus stems from the understanding that compromising such infrastructure demonstrates a capacity to inflict damage during a crisis. The Kremlin has consistently underscored the strategic importance of internet control as a key geopolitical asset. (Source: www.dni.gov/files).

During Russia’s 2014 annexation of Crimea, reports surfaced of tampering with fibre optic cables, resulting in disruptions to local telephone and internet services. In 2017, former NATO submarine force commander, Rear Admiral Andrew Lennon was cited as saying ‘We are now seeing Russian underwater activity in the vicinity of undersea cables that I don’t believe we have ever seen’ and continued by suggesting that ‘Russia is clearly taking an interest in NATO and NATO nations’ undersea infrastructure’.

Russian submarine activity, including the capabilities of the spy ship Yantar, which carries mini-submersibles capable of severing or tapping submarine cables, has been well-documented. Notably, Russian activity often concentrates around critical, deep-sea cables, likely due to the difficulty of repairing such infrastructure. Furthermore, Russia’s primary state-owned telecommunications company, Rostelecom, has been implicated in numerous attacks involving the deliberate rerouting of internet traffic for surveillance purposes. (Source: www.defensenews.com).

In January 2022, the UK’s top military commander sounded the alarm about a hidden danger lurking beneath the ocean waves: Russian submarines. He warned that they’re a serious threat to the undersea cables that are absolutely essential for how we communicate around the world. Admiral Tony Radakin called these cables ‘the world’s real information system’, basically the arteries of the internet, and said that messing with them could be seen as an act of war.

Admiral Radakin pointed out the dramatic rise in Russian submarine activity over the last 20 years, and said that Russia could try to damage or even tap into these cables, which carry almost all of the world’s data. He made it clear: Russia now has the ability to threaten and potentially exploit these crucial undersea links.

| OTHER EMERGING THREATS

So, it is not just one or two countries playing these tricky games at sea. We know that quite a few others are also using these “grey zone” tactics. And they are using all sorts of vessels for this, not just warships; research ships, fishing boats, even coast guard patrols – basically, vessels that are supposed to be doing something completely different.

Reports suggest that North Korea, Iran, Israel, and Turkey have all been using these tactics in the maritime world as part of those tense, militarised disputes that pop up between countries. And they have shown they have got both the will and the way to do this. So far, however, this kind of activity has been observed in the Mediterranean and the Strait of Hormuz.

But there is another related worry: what happens when a civil war spills over into the sea? The conflict in Yemen is a prime example. The waters off Yemen are a major data highway, part of the Europe-Asia cable system, running right through the Red Sea. And we know that the fighting there has already interfered with shipping and maritime security, with reports of naval mines and even divers being used. So, there is a real risk that this conflict could lead to damage to those undersea cables. Basically, any political instability near these cable routes needs to be seen as a serious threat to their safety and reliability.

| NON-STATE ACTORS

When we talk about threats to undersea cables, it is not just governments we need to worry about. Non-state actors, like terrorist groups and criminal organisations, also pose a risk. Terrorist groups, for example, have definitely shown they are willing and able to attack important infrastructure in the past. But, usually, their goal is to cause casualties and get maximum publicity, not necessarily to disrupt the digital economy or financial markets directly.

However, it doesn’t take a lot of resources or sophisticated equipment to damage a cable – think mines or even just divers. So, the risk of a terror attack is real. While a successful attack could definitely cause some damage and grab headlines, it must be remembered that terrorist groups also rely on the internet and digital infrastructure themselves. An attack that knocks out those systems could actually hurt their ability to organise and spread their message, so it might not be their top priority.

A total internet blackout across the EU is pretty unlikely, but the picture changes when we look at smaller European islands, overseas territories, or military bases. The Western Indian Ocean, for example, has seen terrorist activity before, and extremist groups are known to be active there. So, an attack on undersea cables in that region could be aimed at disrupting naval bases, like those used by EU forces in Djibouti or Bahrain. French overseas territories, like La Reunion and Mayotte, might also be at greater risk because they have weaker internet connections. The Red Sea and the situation in Egypt are also worth keeping an eye on, as they’re key points for internet traffic between Europe and Asia, and also known areas of operation for radical groups.

Then there are criminal organisations that rely heavily on digital infrastructure for their operations; things like ransomware attacks, so it makes sense that they might try to exploit weaknesses in the undersea cable network. Experts have even warned that criminals could try to target these cables. While we have not seen any public reports of this happening yet, but there are a number of scenarios to consider.

First, a criminal group could threaten to damage a cable and demand a ransom. It is hard to detect these kinds of threats, especially when they involve things like mines or submersibles which are relatively easy to get a hold of. So, a ransom payment might seem like the easiest option for a targeted country or company, especially if they have weak cable links. This could set a dangerous precedent, though, if word gets out and other criminals see it as a viable business model. That is why it is so important for companies and governments to share information about these kinds of incidents.

Another scenario is that criminals might damage cables to cover up other illegal activities. Disrupting the network could help them avoid surveillance while they are carrying out a smuggling operation, a black-market deal, or some other kind of cybercrime.

| GLOBAL LIFELINES

There are many possible motives for attacking the cable network. If tensions between the West, China and Russia keep rising, damaging a cable might be seen as a way to send a message. Terrorist groups might be tempted by the idea of holding financial transactions hostage. And, as we have discussed, criminal organisations could try to exploit the network for their own purposes. European countries would likely feel the impact of any of these attacks directly.

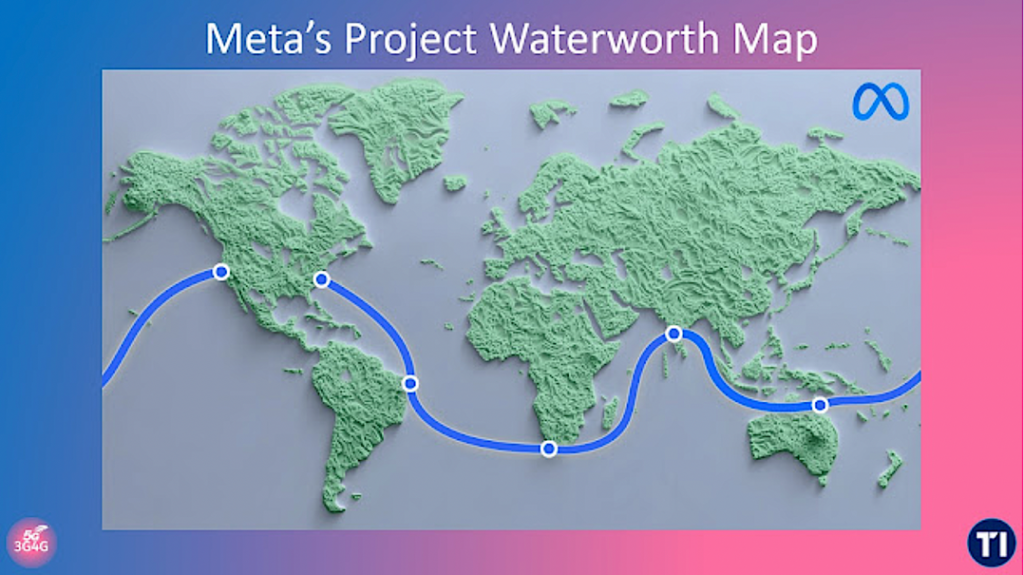

In a groundbreaking announcement on 17 February, Meta (formerly Facebook) revealed “Project Waterworth”, an ambitious, multi-billion-dollar plan to lay a 50,000 kilometre undersea cable connecting the U.S., India, South Africa, Brazil, Australia and other regions. It will be the world’s longest underwater cable project when completed, and would provide “industry-leading connectivity” to five major continents and help support its AI projects. The rising importance of underwater cables has increased concerns over their vulnerability to attacks or accidents. In its blog post announcing the project, Meta said that it would lay its cable system up to 7,000 metres deep and use enhanced burial techniques in high-risk fault areas, such as shallow waters near the coast, to avoid damage from hazards such as ship anchors, interference and other destructive activities, including sabotage.

In a world increasingly reliant on digital connectivity, the safety of undersea communications cables has never been more critical. The stakes are high, and the implications of neglecting their security could be dire, affecting everything from personal communications to international trade.

These cables are not just conduits of information; they are lifelines that sustain our global economy and connect communities across the planet.

james.lookwood@europe-diplomatic.eu