Hermann Stilke: Joan of Arc in Battle (Central Part of ”The Life of Joan of Arc” Triptych) Hermitage Museum

“If all men are born free,” asked the English poet and early feminist Mary Astell in her 1706 book ‘Some Reflections upon Marriage,’ “how is it that all women are born slaves?” It’s a fair and arguably overdue question. Partly, it’s because of religion. Virtually all the major religions cast women in the rôle of homemaker, cook, cleaner, carer for children and elderly relatives and source of amusement for their male partners at bed-time. And, of course, only women can bear children, so if the “lord and master” wants descendants, the only way to achieve that is with the cooperation of a woman. Yes, the man can force himself on a woman and thus produce children but then the act is invariably violent and fuelled by simple lust, not by a desire to procreate. But why should women accept this subservient position in which they have been cast? Cast by men, of course. Yes, a lot of women believe that once they are married with children then they should stay at home and look after the family: an accident of evolution and biology means that they alone are best suited to that task and many of them prefer it that way, as is their right. But not all.

Sex and gender do not mean the same thing. “The term sex indicates biological characteristics, and the term gender indicates the socially constructed characteristics between masculinity and femininity,” says an on-line study paper jointly written by Arjun Sekhar Pm of Kristu Jayanti College, and Parmeswari Jayeraman of Perigar Univiversity. “Gender includes the rules and norms,” they point out, “which exist in each culture about women and men.” However, whatever the rôle society sets for women, however many the constraints it tries to impose, there is nothing physical or mental that can prevent women from rising to the top and taking control.

There have been many examples throughout history. Joan of Arc, for instance, in the 15th century, who led the French forces to defeat England, only to be burned at the stake, allegedly in the name of religion. Long before her, Cleopatra was the last Pharaoh of Ptolemaic Egypt and famed for her brilliant mind. She is also famed for having affairs with Julius Caesar and Mark Antony, although they were of less importance than her intelligence. You may not have heard of her (I hadn’t) but Borte Ujin was the wife of Genghis Khan and empress of the Mongolian Empire, from 1161 to 1230. She ruled the huge empire for long periods – and very successfully – while her husband was away at war. He was away a lot. Engaging his neighbours in bloody battles was certainly more appealing to him than, say, a game of football. The list goes on and on. In more recent times, few in Britain would dispute the strength of Margaret Thatcher’s Premiership, nor her determination. She wasn’t nick-named ‘the Iron Lady’ for nothing.

Look around us today and female leaders are not so unusual, even if they’re not yet “usual” enough. Ursula von der Leyen, for instance, is President of the European Commission. Giorgia Meloni has just become Italy’s first female Prime Minister, as well as leading the country’s first far-right government since Benito Mussolini. But at the same time, sex discrimination continues. A United Nations Report in September 2022 draws our attention to increasing episodes of violence against women, especially those who are most vulnerable.

The 2022 Global Citizen Festival is part of a worldwide campaign calling on world leaders (male and female) to end extreme poverty straight away, including by making funding more easily available, by tackling climate destruction and by empowering women. More than 380-million women and girls are struggling to live on less than $1.90 per day (€1.96 per day). Current research suggests that things are getting worse, too, with even more women and girls living in extreme poverty in sub-Saharan Africa by 2030 than is the case today, while child marriage remains commonplace.

Claudine Uwamwiza is the Senior Investment Officer at the East African Development Bank. She talked about the problems facing poor African girls when she addressed a Brussels Soirée organised by Frank Schwalba-Hoth, a former MEP and founder of Germany’s Green Party. Uwamwiza, originally from Rwanda, told of how she had fled her home country because of genocide, but she was one of the lucky ones: she got out. She told other guests how a lot of young girls get married at the age of 14 because they are so poor and it is the only way to gain enough money to finish school. Those who went to school at all were fortunate, she told her audience. Sometimes they were forced out of school because they had no money. “Some got married at 14 so they could continue their studies,” said Uwamwiza, “although it meant that they had children themselves at an early age.” They don’t get much help from the men, either, most of whom earn a living of sorts from fishing in Lake Tanganyika, the world’s second oldest freshwater lake. But they had to follow the fish, so the teenage mothers were left alone to raise their children, with no nearby help while their men sought the shoals. Violence is still rife with no-one to turn to for help. Worldwide, one woman or girl is killed by a member of their own family every eleven minutes, while 130-million girls remain out of school, denied an education for political and gender-related reasons. One in three of the poorest girls aged from 10 to 18 have never attended classes of any sort while in rural areas 61% of girls do not attend secondary school.

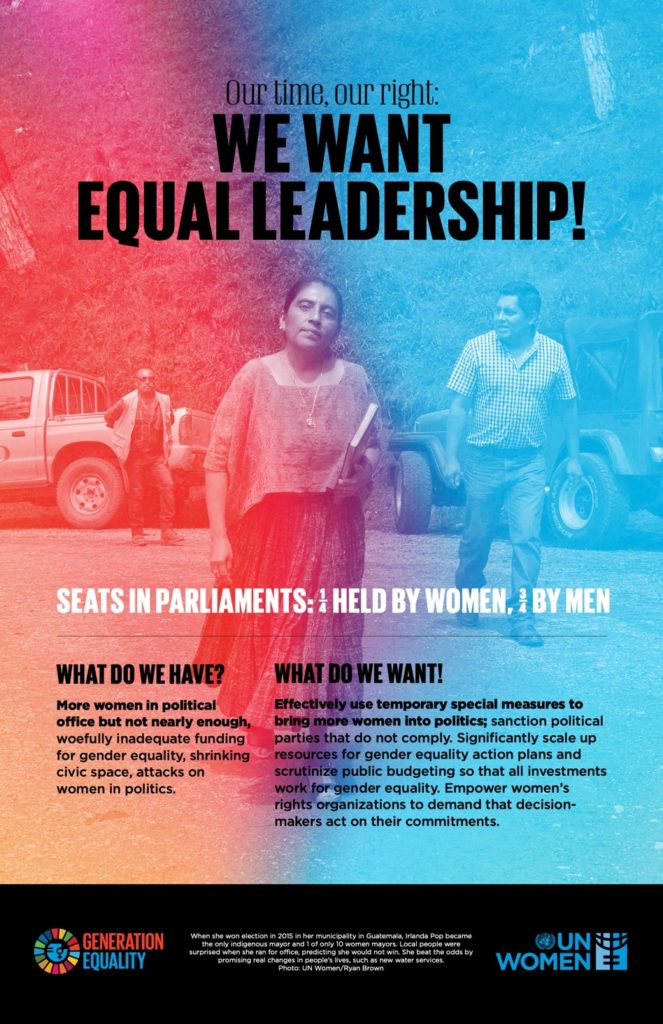

Of course, that doesn’t mean they’ve been idle. They’ve been looking after children for one thing. Globally, women worked 512-billion unpaid hours at childcare, as well as doing household chores. What it means, of course, is that for women affected that way there’s no time left for education, even if it’s available. No time for jobs, either, so no chance to earn money and escape all that drudgery. No money means no escape from food insecurity, for instance, which last year afflicted one in three women around the world. As for jobs, meanwhile, the UN estimates that to get rid of sexist and discriminatory laws will take another 286 years at the current rate of progress. Don’t hold your breath. Just one in three managers or supervisors is female, and women hold only a little over 25% of parliamentary seats in all the various lower chambers. In 23 countries, the UK says, women hold fewer than 10% of the seats, with no signs of early change.

AFTER THE GLOOM, SOME CHEER?

It’s a depressing catalogue of cruel discrimination. The so-called “morality police” of Iran, for instance, mainly target women, not men. But in some parts of the world, women seem to be gaining more public representation and greater political power. There is now, for instance, a group called Women Political Leaders (WPL). It defines its existence on-line like this: “WPL communities are women in political office – Presidents, Prime Ministers, Cabinet Ministers, Members of Parliaments, Mayors. WPL strives in all its activities to demonstrate the impact of more women in political leadership, for the global better. To accelerate, women need three things: communication, connection, community.” What is more, their number are increasing while their determination is growing. “WPL is an independent, international, post-partisan and not-for-profit foundation based in Reykjavik, Iceland (the world champion of gender equality),” says the website. She is clearly a most formidable lady. Silvana Koch-Mehrin is the President and Founder of Women Political Leaders (WPL), the worldwide network of women Politicians. WPL is a foundation that aims to increase both the number and influence of women in political leadership.

Silvana served as Vice-President of the European Parliament (2009-2011) and Member of the European Parliament (2004-2014). Before her time in politics, she founded and ran a public affairs consultancy in Brussels, which later merged with a larger US firm. In addition to her work for WPL, she also serves on the board of the Council of Women World Leaders and is a member of the European Leadership Network (ELN) and a number of other mainly politically neutral organisations that seek to empower the partially (at least) disenfranchised. In 2018 and 2019, she was ranked as one of the 100 most influential persons in gender equality by the organisation, known as ‘Apolitical’. She is a Young Global Leader of the Alumni of the World Economic Forum. She lives in Brussels, Belgium with her three children and their Irish father. Encouraging, but it doesn’t go far enough, according to the United Nations. “Women’s equal participation and leadership in political and public life are essential to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals by 2030,” says the UN’s website. “However, data show that women are underrepresented at all levels of decision-making worldwide, and that achieving gender parity in political life is far off.” There are signs of progress, but not as much as there should be and it’s slow, the website points out. “Women are underrepresented as voters, as well as in leading positions, whether in elected office, the civil service, the private sector or academia. This occurs despite their proven abilities as leaders and agents of change, and their right to participate equally in democratic governance.”

Women face several obstacles to playing a full part in political life. There are structural barriers, such as discriminatory laws, while various institutions still limit women’s possibilities to run for office. “Capacity gaps mean women are less likely than men to have the education, contacts and resources needed to become effective leaders”, the site admits. The 2011 UN General Assembly resolution on women’s political participation notes: “Women in every part of the world continue to be largely marginalized from the political sphere, often as a result of discriminatory laws, practices, attitudes and gender stereotypes, low levels of education, lack of access to health care and the disproportionate effect of poverty on women.” Individual women have overcome these obstacles with great acclaim, of course, and often to the benefit of wider society. But for women as a whole, the playing field needs to be level, opening opportunities for all.

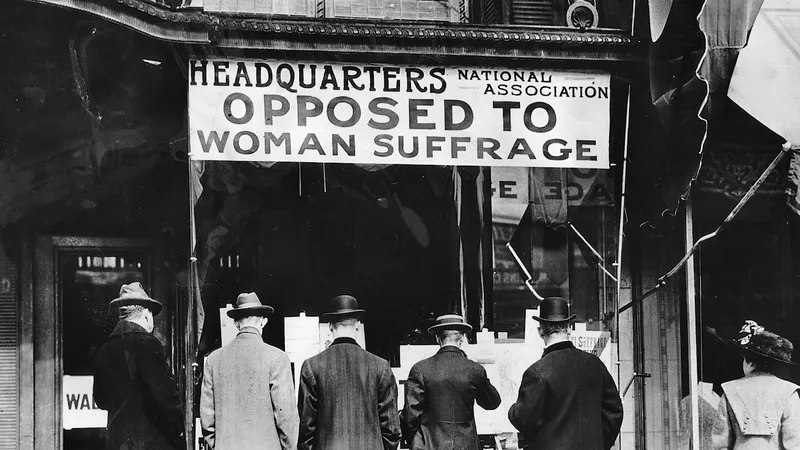

One depressing thing to note is that the Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination Against Women was agreed and signed in New York in December 1979. That’s 43 years ago as I sit here at my laptop writing today, and I still don’t see a revolution taking place. The Convention itself was the culmination of a lot of work which was launched by the Commission on the Status of Women, beginning its work in 1946. That was before I was born and I’m an old man.

Projects aimed at levelling the playing field so that women, like men, can score goals, seem to take an eternity to come to fruition, if they ever do. The UN points out that: “The Commission’s work has been instrumental in bringing to light all the areas in which women are denied equality with men.” I’m sure that’s a comfort of sorts, but it doesn’t really change anything. “These efforts for the advancement of women have resulted in several declarations and conventions, of which the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women is the central and most comprehensive document.” In the great ‘Battle of the Sexes, it’s what Jonathon Swift referred to in 1692 as “The artillery of words.” It’s like the old saying: “Sticks and stones may break my bones, but words can never hurt me.” They can, of course, but not in any way likely to require medical attention, let alone surgery.

Sometimes the UN comes across as rather self-congratulatory and pleased with itself. Yes, it has talked about women’s rights and equality with men for many, many years, but that’s all it’s done: talk. In many instances, women are still denied the rights that are automatically conferred on men. Take, for instance, this example: “The legal status of women receives the broadest attention. Concern over the basic rights of political participation has not diminished since the adoption of the Convention on the Political Rights of Women in 1952. Its provisions, therefore, are restated in article 7 of the present document, whereby women are guaranteed the rights to vote, to hold public office and to exercise public functions.” A reference back to 1952, when yet more words were exchanged and agreed. “But for your words, they rob the Hybla bees and leave them honeyless,” says Cassius in Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar. “Not stingless, too?” Antony replies. “O yes, and soundless too, says Cassius, “For you have stol’n their buzzing, Antony, and very wisely threat before you sting.” In gender politics, it seems, there is no stinging at all, but no end of words.

As of 19 September, 2022, there were 28 countries where 30 women serve as Heads of State or Government, according to the UN Women website, which further points out that at the current rate of progress, we should reach gender parity in terms of power in around 130 years from now. Only thirteen countries have a female head of state (that’s probably fourteen with the election of Giorgia Meloni).

21% of government ministers in Europe were women, while of ministerial portfolios the five most commonly held by women were employment, labour, vocational training, women’s affairs and (somewhat ironically) gender equality. According to the World Economic Forum (WEF): “instilling gender parity across

education, health, politics and across all forms of economic participation will be critical.” That’s probably what they thought back in 1946 and 1952, so the situation demands constant monitoring, which is what the WEF does. “This year’s report highlights the growing urgency for action. Without the equal inclusion of half of the world’s talent, we will not be able to deliver on the promise of the Fourth Industrial Revolution for all of society, grow our economies for greater shared prosperity or achieve the UN Sustainable Development Goals.”

Yes, things have improved and continue to do so, but nothing like fast enough, according to the WEF: “It is forecast to take just 12 years to attain gender parity in education, and in fact, overall, gender parity has been fully achieved in 40 of the 153 countries ranked. Drilling down into the facts and figures, it will take 95 years to close the gender gap in political representation, with women in 2019 holding 25.2% of parliamentary (lower-house) seats and 21.2% of ministerial positions.” But there have been triumphs and it would be wrong to downplay them. According to the website ‘Emily’s List’. women have long been ‘the power behind the throne’; the difference today is that they’re stepping out of the shadows to claim credit for what they’ve long been doing behind the scenes. According to the Forbes website, “While only 5 percent of nations are currently helmed by a woman, the top four spots on Forbes’ 2019 list of Most Powerful Women all went to female political leaders, highlighting the outsize influence they command on the world stage. Collectively, these women oversee $54-trillion (€55.35-trillion) in GDP and more than 3.5 billion people.”

On Forbes’ 2021 list of the world’s most powerful women, not all the names will be familiar. The philanthropist Mackenzie Scott, for instance, or how about Samia Suluhu Hassan, the President of Tanzania, or Kamala Harris, the Vice-President of the United States? Angela Merkel headed the European list as Chancellor of Germany from 2005 until she stepped down at the end of her term of office in 2021.

Christine Lagarde, as head of the European Central Bank, blamed “male group-think” for some of our financial problems in what is very much a male-dominated industry. She wants gender reform and, as a French politician and lawyer, may be in a good position to achieve it. Tsai Ing-wen became Taiwan’s first female leader when she was elected in 2016 and she has caused fear and trepidation in mainland China by making overtures to Washington.

In 2021 Rosalind Brewer was appointed CEO of Walgreens Boots Alliance, the only black woman to take the helm of an S&P 500 company, thus overcoming two different kinds of prejudice.

Closer to home, Magdalena Andersson is Prime Minister of Sweden and leader of the Social Democratic Party. Mette Frederiksen has been Prime Minister of Denmark since June 2019, the second woman to hold the post and also the youngest Prime Minister in Danish history. Natalia Gavrilita is a Moldovan economist and has been Prime Minister of Moldova since 2021.

Kristalina Georgieva is a Bulgarian economist and she was Chief Executive of the World Bank Group from 2017 to 2019, going on to serve as Acting President of the World Bank Group for a few months in 2019.

Ingrida Simonyte is a Lithuanian economist who has served as her country’s Prime Minister since December 2020. Katrin Jakobsdóttir has been Prime Minister of Iceland since 2017 and in 2020 was named Chair of the Council of Women World Leaders.

The list goes on and on, albeit not quite as far as true equality would suggest as appropriate, not only in the field of politics, but also in science and technology, among other things.

Even Margaret Thatcher was a chemist who then studied law before turning to politics.

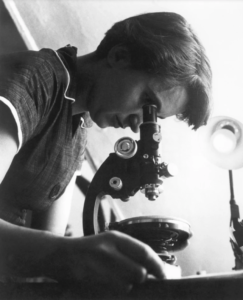

Of course, there are men around the world who try to prevent women from rising to prominence, presumably out of a fear of being overtaken in their own climbs to the top. Women have proved themselves to be every bit as capable as their male colleagues. Even every bit as ruthless on occasions. Politics, though, has tended to be something of a “gentleman’s club”, with few or no provisions for women. But without a fairer system, the human race is denying itself the very skills held most usefully by the distaff side of society. And there have been a great many female scientists, for instance, such as Marie Curie, discoverer of radium and polonium, whose books and papers are still so radioactive that they are kept stored in lead-lined boxes and anyone requiring access to them has to wear protective clothing. There have been female astronauts, too, like Valentina Tereshkova, who has a crater named after her on the moon.

There’s nothing new about women studying the sciences. In Athens in the 4th century BCE, Agnodike trained herself to become a physician or midwife, even though it was supposedly against the law at the time for a woman to be a scientist or doctor. History doesn’t really tell us why. Her story was told by Roman writer Gaius Julius Hyginus in his Fabulae, and she may not have existed other than as an illustration that women could do such work and should be allowed to, even if she had to disguise herself as a man to do it. It all ended happily in Hyginus’ story with the law being changed, although, as I mentioned, Agnodike was probably fictional, not real.

The Women of Influence website conducted a survey to see what are the principle obstacles to women advancing. 42% of the respondents cited a “lack of mentor or sponsor”, suggesting that there are not enough women in prominent positions to encourage others to progress. Others included the difficulty of maintaining a work/life balance and also the fact that a suitable professional network is simply missing. “What women feel they lack the most,” the survey reported, “are meaningful connections with senior leaders who can not only help guide their careers with advice, but also advocate on their behalf.” Other research has suggested that many women – perhaps most – imagine that if they show themselves to be extra competent and able it will automatically lead to promotion. Sadly, that’s not the case. Women need to work strategically. As Forbes puts it: “They should always be asking, ‘Is what I am doing contributing to organizational impact?’ And need to look for ways to benefit both their company and its various markets. By keeping an eye on the outcome of their activities — not just on the activities themselves — women can thereby increase their corporate effectiveness.” They have to overcome favouritism, too, with men most often being the favourites of their mainly male bosses.

Very often, women are not given the recognition they deserve for their achievements. For example, female scientists were sometimes told to give their discoveries to male colleagues to announce, because – they were told – nobody would believe something “discovered by a woman”. It’s just about stupid enough to be true. Given such obstacles to progress and recognition, it’s amazing that women have, even so, succeeded in their chosen field of endeavour. As the British Medical Journal (BMJ) mentioned in an article, back in the 1900s, it was Jocelyn Bell Burnell’s male boss who was awarded the Nobel Prize for proving that pulsars exist.

Rosalind Franklin died before she could contest the 1962 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, which went – famously – to James Watson, Francis Crick and Maurice Wilkins, even though it was Franklin’s x-ray crystallography – used without her consent – that allowed them to decipher the double-helix of DNA. In fact, there have been many famous women scientists.

Marie Curie won two Nobel Prizes for discovering Polonium and Radium; her daughter Irene, working with her husband, discovered artificial radioactivity, winning a Nobel Prize of her own. Emmy Noether developed the theory that became the foundation of quantum physics, thus helping Einstein to formulate the General Theory of relativity.

Ruzena Bajcsy conducted ground-breaking research into robotics and artificial intelligence. Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin discovered that the sun and stars are mainly composed of hydrogen and helium. Rosalind Franklin, after taking x-ray photographs of crystallized DNA, discovered that it takes the form of a double helix.

The list goes on and on. If you want a bit of glamour, Hollywood film star Hedy Lamarr was an accomplished inventor, working with George Antheil during World War II, to develop a radio guidance system for Allied torpedoes that could not be tracked nor jammed. The principles of their work can be found in Bluetooth technology and Wi-Fi. It may be harder to find their names among those credited with the discovery; they weren’t men, after all.