I am still a huge fan of the American mathematician and writer of humorous satirical songs, Tom Lehrer. At the time of writing, he had reached the impressive age of 93 but sadly he no longer writes and records his clever songs which made unspeakable news seem somehow less offensive. I was introduced to his work by a school friend, and we both found his work hilarious. I saved up my pocket money to buy his LPs as well and I now have all his songs in the (slightly) more up-to-date medium of the CD. By the way, such was his mathematical genius at Harvard that Lehrer started teaching maths to undergraduates while he was still a student. He gave up being a satirist, sadly, because he said he felt that satire was made obsolete when Henry Kissinger was awarded a Nobel peace prize. One song, composed in 1964, was about the nuclear arms race, which was rushing ahead at the time as one country after another announced that it had acquired nuclear capability. The song was called “Who’s Next?”.

Lehrer seems to have felt that the rush to come up with an individual ‘nuclear deterrent’ (a ‘bomb’, in other words) was not only fairly pointless but also somewhat dangerous. At the time it was recorded, Ronald Reagan was the outspoken right-wing Governor of California, his time in the White House still lay some way in the future, and in the original version of the song he got a mention which was replaced in subsequent performances (there were a couple of other minor changes, too). Reagan crops up in the last verse as Lehrer jokingly lists possible future nuke-owners, suggesting Luxembourg and even Monaco. “We’ll try and stay serene and calm,” Lehrer sings, “When Ronald Reagan gets the bomb!” (The wording later changed to “When Alabama gets the bomb”). It’s still amusing, although poor old Reagan succumbed to Alzheimer’s Disease, a terrible form of dementia, in which the individual’s brain and thought processes are effectively erased. Nobody deserves to go that way.

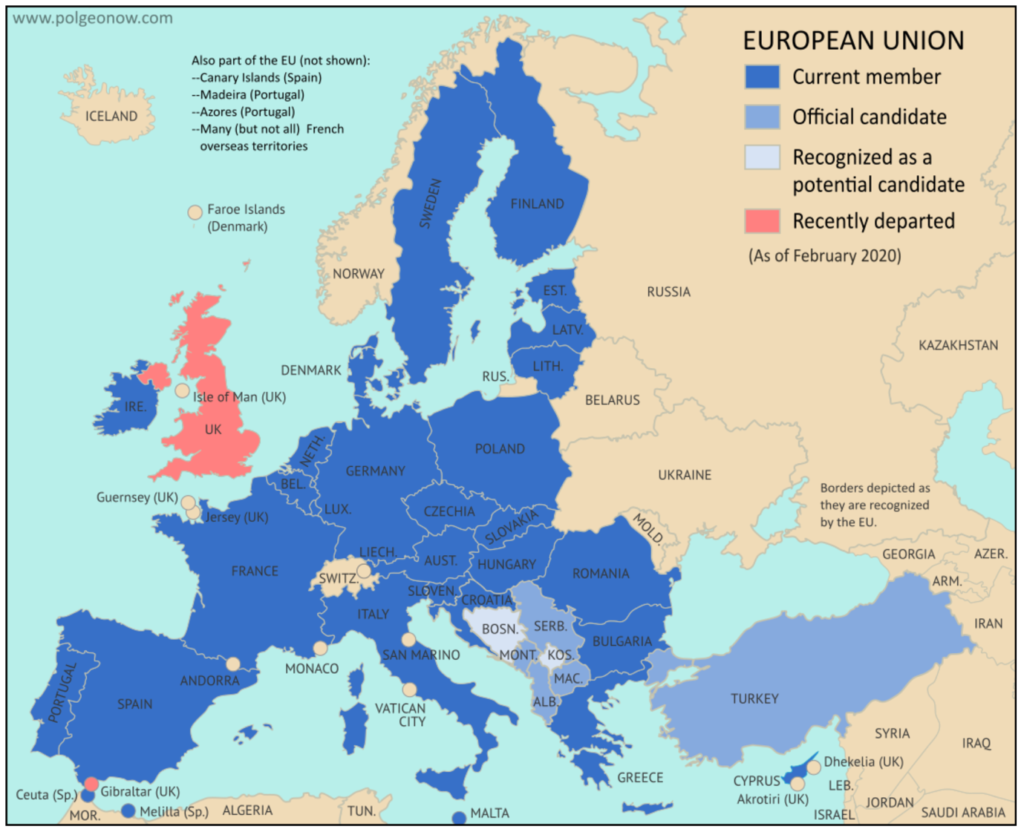

The “Who’s next?” I mean in this article relates to the EU and is a query as to which of the EU’s remaining 27 member states will choose to follow the UK out into the wilderness. The UK left the EU on 31 January 2020, ending 47 years of membership (since described by Britain’s Brexit negotiator as ‘a nightmare time’ but without defining how), since when its government has striven to provoke disputes with its former Continental partners as a way to whip up a little anti-European xenophobia.

The ghost of Napoleon Bonaparte stalks the corridors of Westminster and perhaps Prime Minister Boris Johnson wants to portray himself as the new Duke of Wellington, or even as King George III or his successor, George IV, or maybe it’s as the Prime Minister of that time, Lord Liverpool. It’s all nonsense, of course: the Napoleonic Wars ended on the battlefield of Waterloo in Belgium (I lived not far from the site for a few years, although quite a long time afterwards, of course. It’s a nice little town). Things have not gone altogether smoothly since the UK’s Brexit referendum in June 2016. For one thing, both Scotland and Northern Ireland voted to stay in, but Johnson’s predecessor decided that the opinions of the Scots and Northern Irish didn’t matter. This rather reinforces the commonly-held impression that the view from Westminster encompasses only England (and mainly its better-off southern half). The humorous singing duo Flanders and Swan sang a song about English xenophobia, which they called “A Song of Patriotic Prejudice”. The chorus line goes: “The English, the English the English are best/I wouldn’t give tuppence for all of the rest!” It’s a funny song that’s clearly intended to make us laugh, but it would seem that some people in positions of power take it seriously.

Interestingly, when Theresa May was Britain’s Conservative (Tory) Prime Minister and was facing a referendum in Scotland on its possible departure from the United Kingdom, I interviewed various politicians in Brussels – Conservative, Labour, Liberal-Democrat and Scottish Nationalist – several of whom, including, interestingly, Government-supporting Tory MEPs and visiting junior ministers who were warning that if Scotland voted to leave the UK it would also be obliged to leave the EU and reapply for membership, which it would find very disadvantageous. These same politicians, warning against an accidental departure from the EU and the need to reapply to join as an independent country, have since urged British voters to vote to LEAVE the EU. All-in-all, it sounds like somewhat contradictory advice? Tories were advising Scottish voters: vote to remain part of the UK or you’ll lose your place in Europe and then, a short time later, urging them to vote to leave the EU altogether. Now, of course, a few political groups seem to be calling for their own country’s departure from the EU, whatever that may mean for future generations. In the lead-up to the so-called ‘Big Bang enlargement’ of the EU, there had been prophets of doom who had foreseen problems with some of the Eastern European countries. After years of corrupt leadership, hidden under the billowing skirts of the Communist bloc, those who had climbed the greasy pole weren’t about to slide back down into oblivion with nothing to show for it if they felt they had a chance to reinforce their positions.

IN AND OUT OF THE LIFEBOAT

As a result, we now have people making up words that link particular countries with their own words for ‘goodbye’. One website called ‘Twisted Sifter’ came up with several ideas, such as “Quitaly”, “Abortugal” and (a bit of a cheat this, using the name of a city instead of a country): “Withdrawsaw”. Others on the site include “Czeching Out”, “No longer Remainia”, and “Finnished”. You can come up with some of your own if you like. Most of the ones I found rely on a sort of ‘pun’ that only works in English. None of them is particularly funny, I must admit.

The most commonly proposed name for a Polish decision to leave is ‘Polexit’, which sounds uncomfortably like ‘Polecat’. Former Polish Foreign Minister Witold Waszczykowski, despite holding very conservative views, ruled that out when we spoke last month. “Yes, this is a growing concern in Warsaw and Poland,” he told me, “because we were hoping that the whole project of the European Union would fulfil its promise of everything from economic cooperation, to the free market, the common market, but over these last 20 years, it has tended in a political direction, delegation, and even some policies of a hegemonic character with some countries, especially Germany.”

Waszczykowski accused the European Commission of trying to dictate policy in the EU member states and creating its own laws, but he thought it unlikely that his country would seek to find the way out. Poland, he told me, is a European country, and having seen how the Nazis wanted to dismantle it, it is less likely to go its own way.

Although some have pointed out that Britain’s departure was “successful” (in that no blood was spilled and there was no physical violence) Markus Gastinger of the University of Salzburg thinks the British example will put people off taking that route. It’s interesting to note that some of the people predicting a rush for the doors after the UK’s departure are those politicians who most strongly urged Britain to leave, so this could be merely an attempt to put flesh on the bones of a forecast based more on wishful thinking than on careful analysis and inside knowledge. It would also make Britain’s “Brexiteers”, as they’re often called, seem less lonely. In an article for the website of the London School of Economics (LSE), Gastinger reminds us that “one argument among Brexiteers in the run-up to the referendum was that the UK needs to break free from the EU as a ‘failing political project’, a mantra repeated by Leave supporters to this day.” However, he then adds another point: “But how likely is it that the EU will fail?” Gastinger believes there are just two scenarios in which the EU could collapse. The first of these, which looks about as likely as NASA finding a colony of gnomes on Mars, is that all the remaining member states would agree together unanimously (an unlikely eventuality at the best of times) simply to change the Treaties and dissolve the EU (perhaps those unexpected gnomes could put it back together again whilst humming Beethoven’s ‘Ode to Joy’?). This eventuality is remote enough to merit a place in a book of fairy tales. Gastinger mentions another possibility which looks to me to be almost, but not quite, as unlikely as the gnomes. He suggests that if the UK’s departure is extremely successful, then quitting the Union could be seen as a viable option in a case of serious disagreement.

The table Gastinger produces for his article shows that the UK was positioned very close to the exit from some time before the referendum. However, it also shows that since Brexit the remaining member states seem to have pulled more closely together.

Only Italy has figures that hint at possible departure, but then only 39% of Italians say they lack a ‘European identity’, compared with 63% in the UK prior to the actual referendum. A lot of that can be attributed to a British media that was (and still is) universally hostile to the whole ‘we’re part of Europe’ attitude. Some of the leading popular newspapers seem to have abandoned any attempt at telling the truth as far as EU issues are concerned, adopting instead an unshakeable ‘us and them’ approach. Reading some of these so-called “red-tops” (because their banner titles are often printed in red) one might think that the UK was at war with Europe. As far as the UK is concerned, most of those who campaigned for “leave” have done well personally, but not all of them. Take Dominic Cummings, for instance, an ardent long-term campaigner for Britain to leave the Union, who was also nicknamed “the rudest man in Westminster” for his cavalier attitude to MPs, civil servants and the media. He lost his place, however, and now snipes from the sidelines. On the other hand, a middle-ranking diplomat, David Frost, suddenly emerged to carry the banner of separatism alone, and this propelled him swiftly to the top of the tree, which included getting a peerage. He is now (despite never having been elected) the Minister for Brexit, and is often seen on television, despite having been seen by many contemporaries as ‘mediocre’ when at Oxford University.

The Guardian newspaper gave an interesting assessment of the hardest-possible Brexit, for which Lord Frost was responsible. “The most damning criticism of the Brexit that Frost negotiated is that not one industry or trade can say that, however greatly others are suffering, we at least are benefiting from being outside the EU. Even fishermen and women, whose precarious lives were exploited with such cynicism by Nigel Farage (an ardent Brexit campaigner and founder of the Brexit party) and Boris Johnson, are finding they must fill in 71 pages of paperwork to export one lorry of fish, as new bureaucracy extends to every fishing village in the land.”

The UK government’s refusal to permit temporary visas that are long enough to be appealing have left the country with severe shortages of health workers, agricultural workers, and long-distance lorry drivers, but the ‘red-top’ newspapers are blaming that on an intransigent EU. In tabloid-speak, Britain can never be wrong, the EU can never be right. The readers apparently never question this, nor check if the “facts” they’ve just read are correct. I once had a disturbing and somewhat heated telephone conversation with a friend who couldn’t understand why the First Minister of Scotland, Nicola Sturgeon, would want to keep her country in the EU “where people don’t even speak our language”. It’s an interesting point of view, but Lord Frost’s antipathy towards hearing any other tongue but English is strange given that his degree was in French and European History.

EVERYONE IS TO BLAME (EXCEPT ME)

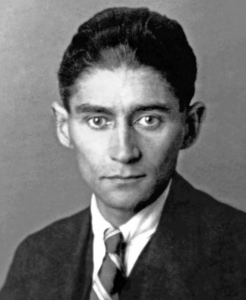

This fixation in the UK with apportioning blame anywhere but Westminster probably originates in the lingering annoyance with the fact that Britain once had an empire and no longer does. The Guardian article quotes the great Czech writer, Franz Kafka, who wrote ‘The Trial’ and ‘The Metamorphosis’, giving rise to the term ‘Kafkaesque’ to describe too much bureaucratic paper being needed.

In describing the immediate aftermath of an Earth-changing event, he wrote: “Every revolution ‘evaporates and leaves behind only the slime of a new bureaucracy’.” The Guardian, perhaps unsurprisingly, adds this to its Kafka quote: “Britain’s Brexit revolution is evaporating now and leaving behind the slime of David Frost.” This unrelenting driver of the hardest of hard Brexits felt that EU membership had put chains on British ambition. He perhaps should have recalled another Kafka quote, this time from ‘The Trial’: “Es ist oft besser, in Ketten als frei zu sein” (“It’s often better to be in chains than to be free”). Perhaps the UK’s former partners lack the Frost effect: a middle manager with ambitions but without much backing or high plaudits and so relying on shock tactics (or a sudden change of tactics) to make an impact.

Even so, there are other possible escapers from the EU fold. Much may now depend on Angela Merkel’s successor. Merkel herself had the nickname ‘Mutti’, which translates as “Mommy”. She is popular, too, by and large, and extremely clever; even her political enemies seem to respect her. She modelled herself on Marie Curie, the first woman ever to win a Nobel Prize. She has degrees in quantum chemistry and physics and was the only woman occupying a position in the theoretical chemistry section of the East German Academy of Science.

Not a bad record. Mainly raised in the former East Germany (the German Democratic Republic or GDR) she is a fluent Russian-speaker but she dislikes Vladimir Putin who, knowing Merkel’s fear of dogs, deliberately let one into the room where negotiations were taking place, just to discomfort her. Hardly a diplomatic act, but then Putin is no diplomat. So, she commands the ear of many and even those who don’t much like her, respect her. Apparently, she also does very telling impressions of other leaders, which I would love to see. Perhaps we shouldn’t read too much into that particular skill, however; the late Serbian leader Slobodan Milošević used to do it to entertain journalists while we were awaiting the outcome of meetings. His impression of former president of Croatia, Franjo Tuđman was so lifelike that it was difficult to record an interview with Tuđman immediately after watching Milošević doing that particular impression without laughing.

Gastinger’s research suggests that the remaining EU states have moved closer together since Brexit. At the extreme ends of the scale, the largest and smallest are unlikely ever to go for being on their own. It’s only possible to make a quasi-joke out of it by mixing German and English as others have done (it’s not funny in either). So how about “Tschüss to be alone” (“choose to be alone” in sound but actually meaning ‘ta-ta to be alone’, which makes no sense at all) for the Germans and perhaps for Luxembourgers you could have, “äddi-subtracti”, which sounds like ‘add-subtract’ but which is closer to ‘ta-ta subtract’).

Let’s face it, both Germany and Luxembourg have far too much to lose to risk a walk on the wild side without company. Unlike the UK, both would also have difficulties in abandoning the euro and establishing a new currency, as would Italy. When I was regularly covering meetings of the European Council when it was held in Luxembourg, I learned how to ask for beer in Luxembourgish because I found I got prompter service in the Council press bar that way. The dictionary says it’s “zwéi Béier, wann ech glift”, but I was told it should be “zwéi Humpen, wann ech glift”, to indicate that I meant beer on tap, rather than the bottled variety. It seemed to work, although smiles from the bar staff at the Council were rare. In any case, I never met a Luxembourger who wasn’t also extremely proficient in French, German and, by and large, English.

Some post-Brexit surveys have suggested that a few more UK voters now anticipate a future outside the EU in a more favourable light, but mainly because it means that the years of all that “in–out” wrangling have finally come to end. At the same time, British attitudes towards immigrant have turned positive. No, I don’t know why, but it seems that around 70% of British respondents view immigration positively, compared with just 53% at the time of the referendum, when some of the tabloid newspapers were talking about Britain being ‘swamped’ with foreigners back in June 2016. Some British newspapers still write leading articles about the numbers trying to get to the UK and how the French are not really trying to stop them. They also write about the incomers ‘taking British jobs’ and occupying British houses, but at a time when certain jobs previously done by immigrants are now not being done at all, I wonder if the message is having quite the desired effect? “Foreign drivers take our truckers’ jobs” as a headline sits badly alongside “unhelpful EU stops drivers from working in Britain”.

It is a fact – sad but true – that there are people in Britain who are quite happy to blame Europe for everything, but who still fancy holidaying on the Costa del Something-or-other when the weather turns warm.

WIN SOME, LOSE SOME (BUT LOSE MORE)

If Britain’s former co-members of the EU are looking for the advantages they might gain from following the UK’s lead, they’ll need a powerful magnifying glass and a forensic attitude to clues. Those who voted Leave, or at least those who did the cheer-leading for it, remain convinced that it was the right thing to do, without ever, in most cases, being able to explain how or why. They still seem to believe that the EU will ultimately fail but cannot explain in what way that might happen. One possibility, however remote, in Gastinger’s opinion, is that the EU could be “hollowed out” by individual, perhaps widely-spaced, departures as individual member countries opt to go their own ways. If the mountain of paperwork that has now sprung up for those seeking to import or export between the UK and the EU is anything to go by, the “cross-border trading” option between the Union itself and an individual former-member seems unlikely to win many supporters.

To begin with, Britain’s response to, for instance, the arrest of the British-registered scallop dredger, Cornelis Gert Jan, owned by MacDuff Shellfish of Scotland, was bluster, backed up by threats. The boat has now been released after its Irish skipper, Jondy Ward, appeared in the court of appeal in Rouen. He still faces a trial in Le Havre in August, 2022, charged with non-authorised fishing in French waters by a boat from outside the European Union, which carries a maximum fine of €75,000. The actual legal situation remains unclear at the time of writing and the whole affair seems to have more to do with posturing than justice.

Would such issues persuade others to follow Britain out of the EU? Not according to Brendan Donnelly, Director of the Federal Trust for Education and Research. “During the 2016 referendum advocates of Leave often claimed that other countries would follow the UK in leaving the EU,” he told me. “The reality has turned out to be very different. The chaos of Brexit has reinforced the prestige and cohesion of the EU. Even in countries like Hungary and Poland, where certain leading politicians encourage Eurosceptic sentiments, public opinion has looked at Brexit and decided that the British example is not one to be followed. The reports in the British press of the collapse of the EU are wishful thinking, not serious reporting.” The problem is that the negotiations for quitting the EU were never completed, the government’s claimed ‘oven-ready deal’ never existed. Furthermore, the UK has reneged on several of the promises it made.

Take, for instance, the mess over Northern Ireland. While Britain was inside the EU, trade across the border between Northern Ireland (which is part of the UK) and the Republic of Ireland was straightforward and unimpeded. With Britain outside, border checks have become inevitable, and so would a physical barrier of some kind between the two, which nobody wanted. It was made the subject of a protocol which Britain has already broken. Step forward, Lord Frost, once again. In a badly received speech that he made, he cited the so-called ‘father of Conservatism’, Edmund Burke, before laying all the blame for the current confusion at the door of Brussels, although it is caused by the agreement he cobbled together and the fact that the British government chose the hardest-possible Brexit, with Britain outside not only the Single Market but also the Customs Union.

This put the agreement that brought peace to the island of Ireland and ended ‘the Troubles’ at dire risk. Lord Frost insisted that the agreement secured ‘balance’, but it never did, according to Stephen Barber, Professor of Global Affairs at Regent’s University London and Senior Fellow of the Global Policy Institute. “The fundamental difficulty is that we are being asked to run a full-scale external boundary of the EU through the centre of our country, to apply EU law without consent in part of it, and to have any dispute on these arrangements settled in the court of one of the parties.” The fact that it doesn’t work would be embarrassing for Boris Johnson, which is why he and his supporters seem to have resorted to mud-slinging. The Government accuses anyone who rocks the boat of wanting to see Brexit fail. Those who orchestrated this unworkable plan are happy not to mention Brexit at all, claiming it’s done and that’s that. “They have been no more sensitive to the fragility of the Northern Ireland settlement than they have to the traditions of Parliament, which Johnson attempted to prorogue,” wrote Professor Barber, “or the institutions of the judiciary which were undermined as ‘enemies of the people’ (for questioning Johnson’s right to prorogue parliament illegally). The failure to ‘Get Brexit Done’ could pose political risks to the government and that is perhaps why, even where it genuinely wants to revisit the Protocol, constructive discussions remain undermined by point-scoring and political attack.”

It’s very sad for those living there but also for those of us who reported on the frequent meeting and negotiations between such notables as John Hume and Ian Paisley, who buried their differences long enough to find common ground.

I can only assume that those who remain supportive of Lord Frost’s views have never visited homes where strong wire defences have had to be erected over people’s gardens to keep out petrol bombs, nor have they seen the barriers across parts of Northern Ireland between Republican and Loyalist areas.

Those differences are likely to remain; a Sinn Fein Belfast councillor I interviewed long ago still recalled how he and his friends (and enemies, I suppose) used to gather along the line between Catholic and Protestant communities in Belfast’s Alexandra Park for what he described as ‘recreational violence’, which more closely resembled football hooliganism than the bombs and bullets that came later and which scarred the North for so long. That sort of traditional hostility doesn’t die out overnight when it has lasted for decades or even centuries. Oddly enough, Ian Paisley, that fiercely protestant pastor and leader of the largest unionist party in Northern Ireland ended up on very good terms with Martin McGuinness, a Sinn Féin politician and former commander of the Provisional IRA, introducing him to me in Brussels in friendly terms. They seemed to get on very well.

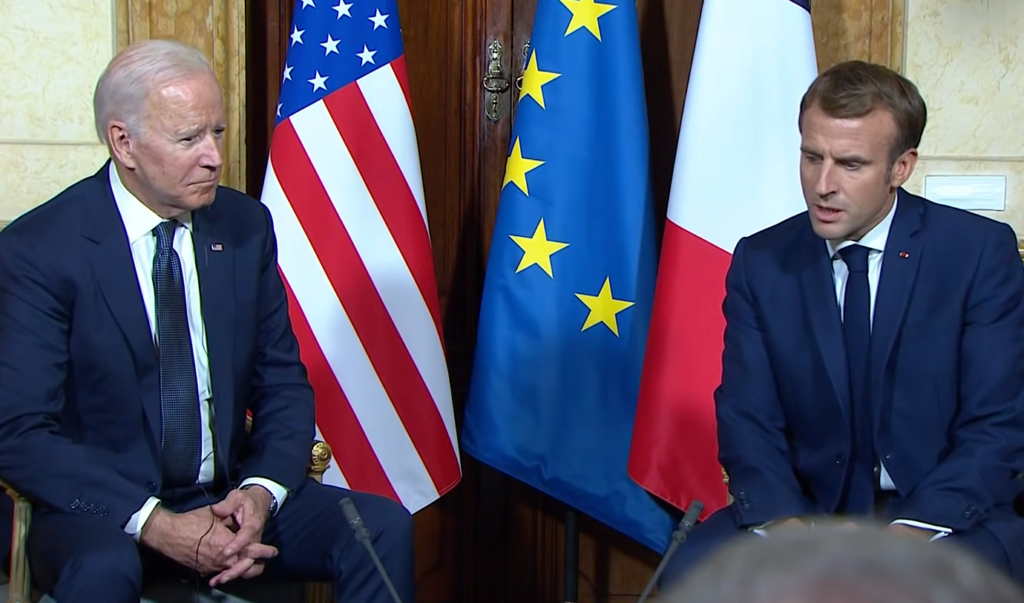

The Office for Budget Responsibility is now forecasting that the economic damage caused by Brexit will be twice as serious as that inflicted by Covid-19. It is difficult to believe that the signing of marginally beneficial trade deals with far-away countries like Australia and New Zealand will do much to convince British public opinion that Brexit is going well. The Australia deal, known as AUKUS (Australia, UK and US) is arguably the most controversial, involving Australia and the United States in an agreement that provides Australia with nuclear-powered submarines which use American technology. The problem is that Australia already had a deal with France for twelve conventional submarines. Quite apart from the EU, France is supposed to be a close defence ally under the Lancaster House Treaties, agreed in 2010. Britain only told Paris that Canberra was reneging on its deal with France two hours before the AUKUS agreement was formally announced. France withdrew its ambassadors to the United States and Australia but not Britain, which the French believed had merely seized an existing opportunity. It is, however, a clear breach of confidence with a long-time partner and ally. Britain doesn’t even get much out of it since the technology involved is American. It does demonstrate, however, how much Britain’s defence policy is now dictated from Washington. This will not have gone unnoticed in the EU.

Britain looks set to lose out in other ways, too. Before Brexit, getting close to the UK was seen by India as a good way of cosying up to the EU. New Delhi now sees Britain as a less important ally in that regard, especially as the EU now views the Indo-Pacific region as strategically more important, even appointing its own envoy for the region. Dr. Karine de Vergeron, Associate Director and Head of the Europe Programme at the Global Policy Institute (GPI) in London, stresses the changed geopolitical reality and why it matters. “The Indo-Pacific creates 60% of global GDP, two thirds of global growth and 30% of trade to the EU passes through the region.” She also makes an interesting prediction: “After Brexit, the forthcoming French presidency of the EU starting next January will no doubt seek to bolster European defence as a priority. It will be an interesting test of the EU’s capacity, freed from British restraint, now to engage in significant new steps towards further integration.” It would seem unlikely that a France that leads the EU and whose big Australian contract was scuttled with British efforts will look with friendly eyes across the Channel.