© Coe.int

It was former US President Barrack Obama who said: “We have to uphold a free press and freedom of speech – because, in the end, lies and misinformation are no match for the truth.” No match, perhaps, in terms of what we have a right to expect, but it’s a position that’s surprisingly difficult to uphold. Bias has a habit of creeping in, for whatever reason. The Cambridge English Dictionary defines ‘bias’ as: “the action of supporting or opposing a particular person or thing in an unfair way, because of allowing personal opinions to influence your judgement”. In many fora, evidence of bias is clear. Most people prefer to buy newspapers (if they bother at all in these days of electronic communication) that reflect most closely their own political views.

It’s hard to imagine Leon Trotsky, for instance, buying Britain’s Daily Telegraph or Daily Mail, nor Donald Trump bothering to read the Morning Star, although I’m sure that these publications have their virtues and their ardent readers, who believe their conflicting versions of events in full confidence of their veracity. However, with printed news, everyone knows where they stand. With social media it’s not always quite so clear. As the 16th to 17th century English philosopher and member of parliament Francis Bacon wrote in one of his essays: “What is truth? said jesting Pilate; and would not stay for an answer.” He was clearly aware that there were politicians around back in New Testament times, too. I should think the Stone Age had a few as well.

Many of us these days get much of our information about the world from social media platforms. It’s often quite hard to tell which way they lean politically, although Britain’s Sun newspaper, itself fairly far to the right, has accused Google of having a pro-left-wing bias. This apparently comes from research conducted at two US universities, Columbia and Northwestern, which claims to prove that Google’s list of top stories contains disproportionately few items from right-wing websites, such as Fox News.

In other words, the news it shows is seldom favourable to Donald Trump and his supporters or of Britain’s departure from the European Union. The newspaper alleges that Google prefers to direct people to left-wing news sources. Mind you, these supposedly left-wing sources are hardly radically Trotskyite either. They are, in fact, CNN, The New York Times and The Washington Post, not exactly beacons of Socialist revolution. The Sun, however, is undeniably (and unashamedly) right-wing in its political bias.

A London School of Economics report into how the media treated a far-left challenger for leadership of the Labour Party, Jeremy Corbyn, when he was seeking selection concluded that he had received unfairly negative coverage.

“Hate speech in some traditional media, particularly tabloid newspapers, continues to be a problem,” it concluded, “with biased or ill-founded information disseminated about vulnerable groups, which may contribute to perpetuating stereotypes.” The report singled out an article by Sun columnist Katie Hopkins about the continuing influx of migrants trying to cross the English Channel. In an article headed “Rescue boats? I’d use gunships to stop migrants”, Hopkins went on to describe migrants as “cockroaches” and “feral humans” and proposed that gunboats should be dispatched to prevent further arrivals by sinking the craft in which they are trying to arrive. She is not the only public figure (if a columnist can be described as a ‘public figure’) to have suggested such a drastic solution. When the far-right British National Party (BNP) won two seats in the European Parliament in 2009, its leader, Nick Griffin, was interviewed on BBC television, where he recommended that the EU should “get tough” with asylum seekers, sinking their boats in the Mediterranean. The interviewer, Shirin Wheeler, said she could not believe the Union would engage in murder at sea. In response, Griffin replied: “I didn’t say anyone should be murdered at sea – I say boats should be sunk, they can throw them a life raft and they can go back to Libya.” It’s certainly a controversial point of view, if not totally without its supporters.

He continued: “But Europe has sooner or later to close its borders or it’s simply going to be swamped by the Third World.” No other political group, including far-right parties such as Geert Wilders’ Dutch-based ‘Freedom Party’ would sit with them in the European Parliament chamber. Wilders described the BNP’s immigration policies as ‘disgusting’. In a BBC interview recorded inside the European Parliament building in Brussels, Griffin said he was “disappointed but not surprised.” When asked about Wilders’ comments he told the BBC’s Shirin Wheeler: “I’ve no doubt at all that he is responding to things that he’s heard that we’re supposed to have said or alleged to have done, which is very often liberal-left media propaganda, and which simply isn’t true.” Griffin and his BNP colleague, Andrew Brons, lost their seats in the next European election and Griffin was subsequently expelled from the party he’d led, accused of trying to ‘destabilise’ it.

FREEDOM OF THOUGHT?

We are wandering away from the problems of policing social media sites, although the issues are closely linked. According to the Council of Europe, freedom of expression and freedom of the media – including social media – are protected under Article 10 of the European Convention of Human Rights. It is supposed to guarantee freedom of expression, “underpinned by legal guarantees for independence and diversity of media and safety of journalists and other media actors”.

Try telling that to the journalists of Belarus, where Alexander Lukashenko still insists that he was fairly-elected as leader, with an amazing 80% of the popular vote. Most Belarussians appear to disagree on the ‘fairness’ point (not to mention the 80% claim). Several foreign journalists have since been deported while others, including native Belarussian journalists, have had their media accreditation withdrawn. Among them were a video journalist and a photographer from Reuters news agency, two from the BBC and four from Radio Liberty. Many others have been ordered to leave, with Lukashenko accusing them of being part of a Western plot to get rid of him. Perhaps most significantly, Lukashenko still enjoys the support of Russian President Vladimir Putin, whose interest in personal power seems to far outstrip his commitment to democracy.

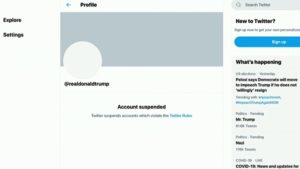

It would be wrong and inconsistent to ignore some of the allegations concerning social media and its misuse, however. There would certainly appear to be some examples of uneven treatment by and of social media platforms. As Al Arabiya reported in July 2020, Twitter had come under fire over a decision that seemed to permit Iran’s Supreme Leader, Ali Khamenei, to call for genocide in Israel and the deaths of Jewish people on its platform, whilst simultaneously censoring Tweets by the then President, Donald Trump, for writing that looters rioting in Minneapolis would be shot. Not surprisingly, Trump and his many supporters considered this to be a mite unfair.

The issue was even raised at a hearing held in the Israeli parliament, the Knesset, attended by a Twitter official. Human rights lawyer Arsen Ostrovsky asked why Twitter had begun to flag up tweets by Trump, but not those of Iran’s Khamenei who, Ostrovsky pointed out, “has literally called for the genocide of Israel and the Jewish people” on its platform. Twitter’s Head of Policy for the Nordic Countries and Israel (an odd grouping, I’d have thought), Ylwa Petterson, appearing by video link, explained that “Foreign policy sabre-rattling on political or economic issues are generally not in violation of our Twitter rules.” Again, this comes from Al Arabiya’s remarkably balanced coverage: Petterson faced a question from Israeli parliamentarian Michal Cotler-Wunsh, double-checking that from Twitter’s perspective it’s OK to call for genocide but not to comment on a domestic political situation, even if some of the Minneapolis rioters were also said to be looting.

Trump’s Tweet, Petterson explained, was “violating our policies regarding the glorification of violence” and could therefore cause harm. Twitter had not, at the time of the hearing, added any warnings about Khamenei calling for “armed resistance”, describing the destruction of Israel as the removal of a “cancerous tumour” and Zionism as in need of being uprooted. The encounter angered US Republican Senator Ted Cruz, who pointed out that while Twitter chooses to censor “free speech of many conservatives – including the President – the Ayatollah Khamenei’s account remains active and is still posting anti-Semitic Tweets”. Perhaps Twitter has never read the views of the great French painter, Henri Matisse, who wrote: “Ce que je rêve, c’est un art d’équilibre, de pureté, de tranquillité, sans sujet inquiétant ou préoccupant, qui soit…un lénifiant, un calmant cérébral, quelque chose d’analogue à un bon fauteuil qui délasse de ses fatigues physiques.” (What I dream of is an art of balance, of purity and serenity devoid of troubling or depressing subject matter…a soothing, calming influence on the mind, rather like a good armchair which provides relaxation from physical fatigue). Twitter should, perhaps, take up painting.

EVEN-HANDED?

The social media giants stand accused of trying to exert undue influence over people who perhaps presume the content they read is checked for its veracity and fairness. It isn’t always, at least not in the way you might expect. Take this article from Gulf News, based in the United Arab Emirates: “Most mass media the world over practise some kind of tyranny, even if it looks less flagrant than political despotism. Doesn’t the media usually manipulate the minds of people almost everywhere in the world? Doesn’t it form their likes and dislikes? Isn’t it the media that sets cultural, social, artistic and political norms whether you like them or not?” It’s true, of course, but the question here is not so much whether or not it influences our decision-making as whether or not it does so in a fair and balanced way. No, according to Gulf News. “Media dictatorship, in actual fact, is more difficult to combat than political dictatorship. Whereas the latter is as clear and noticeable as a boil on the face, the former is like cancerous cells which can hardly be noticed or identified by the ordinary man.” Of course, the reader can always go to a different post on another platform that complies more closely with his or her views.

Early in January, the National Review, a conservative publication, drew attention to an example (by no means the first) of double standards being applied with regards to the national origins of a particular story. “Twitter’s decision last week to permanently suspend Representative Marjorie Taylor Greene’s account calls attention to the company’s permissive attitude toward accounts operated by foreign authoritarian regimes,” says the article. She had contravened Twitter’s Covid Misinformation Policy by casting doubt on the efficacy of vaccines.

However, they did nothing about similar anti-vaccine campaigns on Twitter by accounts affiliated to the Russian and Chinese governments. Take for example the death of Carlos Tejada, the Pulitzer Prize-winning Foreign Editor of the New York Times, who died one day after receiving a Moderna booster shot. The jab and the death, according to doctors, were not connected (Tejada is said to have suffered a heart attack) but Global Times, a media source linked to the Chinese government, not only suggested otherwise but went on to gloat about the death as if in celebration. “Looking forward to more details by the NYT. It’ll be a good commemoration of Tejada, who won a Pulitzer for slamming China’s COVID-19 performance,” said its Tweet. The Global Times continued to suggest, unhindered by Twitter, that the Moderna jab is dangerous. It also routinely verifies Chinese government-backed sites that deny Chinese atrocities. Russia also regularly suggests that the Pfizer vaccine is less effective than its own Sputnik V version, even though tests in the West suggest Sputnik V has little or no effect on the Omicron variant. Not being either a biochemist or a virologist, I cannot honestly comment on the issue, nor gauge who (if anyone) is telling the truth here. Public perception and national pride seem more important to the Russian and Chinese authorities than human life. However, it would seem that posts by potentially hostile governments are exempt from any form of control, however dangerous they may be.

There have been some whistle-blowers who have revealed things about social media platforms their owners would have preferred to remain hidden. Take the case of Frances Haugen, a former product manager with Facebook. When she left her post, she took with her copies of certain documents that she subsequently shared with the Wall Street Journal, showing that the company had long prioritised “growth over safety”, as she put it. Among the revelations, the papers seemed to show that Facebook treated celebrities, important politicians and other influential people differently from the general public by not checking what they were posting. The leak also revealed that a group of Facebook shareholders were bringing a lawsuit against the company, alleging that the $5-billion (€4.4-billion) payment it made to the US Federal Trade Commission to settle the Cambridge Analytica data scandal was set so high in order to save Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg from personal liability. The scandal erupted after executives from the UK election monitoring company, Cambridge Analytica, had been recorded boasting about how they had harvested data from Facebook to help secure electoral victory for Donald Trump and also the UK vote to leave the EU. Haugen’s revelations included the fact that Facebook’s research had revealed the negative impact of its subsidiary, Instagram, on teenagers, with some 32% of teenage girls saying that if they had felt bad about their bodies, Instagram had made them feel worse. The report was suppressed, and Facebook had claimed that Haugen’s revelations ignored the positive effects of Instagram. She was unmoved. “There were conflicts of interest between what was good for the public and what was good for Facebook,” she said. “Facebook over and over again chose to optimise for its own interests, like making more money.” Zuckerberg has also been accused of harvesting personal data and using it to influence world politics. It seems to be widely accepted, however, that the algorithms exploit users’ data for advertising and marketing purposes.

IF YOU THINK SOCIAL MEDIA IS BAD, GOING WITHOUT IT IS WORSE

While many of us moan about social media being biased or unfair, it remains an important tool. Otherwise, countries facing unrest, such as Kazakhstan, wouldn’t try to quell anti-government riots by closing the Internet. That is what they’ve done, however, and Al Jazeera quotes the internet monitoring group, Netblocks, as saying that connectivity levels plunged to zero as a consequence. “Kazakhstan is now in the midst of a nation-scale internet blackout after a day of mobile internet disruptions and partial restrictions,” the NetBlocks monitor tweeted. “The incident is likely to severely limit coverage of escalating anti-government protests.” We are left to wonder: if the internet had existed during the French Revolution, would Maximilien de Robespierre, strong opponent of slavery and imperialism, have retained his head? His social media postings would have been interesting.

Restrictions on social media don’t always feature in attempts to quash protests, according to Stanford University’s Spogli Institute for International Studies. Look at Belarus, still run by the man sometimes referred to as ‘Europe’s last dictator’, Alexander Lukashenko.

“Although the Belarusian government has placed significant restrictions on the media,” says a report conducted by academics, “Belarusian citizens enjoy somewhat untrammelled internet access. This has played a significant rôle in the protests, since online outlets are Belarusians’ main source of uncensored news.” The government did, however, cut off access to many of the social media sites. The questions remain, however, over the influence of social media. “These are complicated questions that will not be settled any time soon,” says the report. “But the Belarusian protests are a reminder that social media can be an important tool for pro-democracy activists, especially when authoritarian governments have monopolized other media. It also allows Western state media, such as Radio Liberty and the BBC, to reach receptive audiences.” The whole report is long and extremely interesting, and I recommend you to read it at the following web address: https://fsi.stanford.edu/news/no-modest-voices-social-media-and-protests-belarus

Don’t think for a moment that everything is hunky-dory in Belarusian social media circles, of course. Take the case of Yegor Dudnikov, a Russian citizen put on trial in Minsk for allegedly preparing materials that urged insurrection against Lukashenko. He claims he was beaten by police before receiving an eleven-year jail sentence, which sounds somewhat disproportionate.

According to Radio Free Europe, “Dudnikov placed at least 55 posts about the protests on the Telegram channel administered by the so-called Groups of Civic Self-Defense of Belarus (OGSB), an organization labelled as extremist and banned in Belarus in the aftermath of the protests.” Dudnikov is just one of many anti-Lukashenko protestors to have been jailed. One of Belarus’s oldest civil rights organisations has been declared “extremist” (anyone who is not an ardent admirer of Lukashenko is seen as dangerous). Of course vicious regimes centred on one tyrant never have difficulty recruiting thugs to beat up its opponents. Meanwhile, Radio Free Europe’s service has also now been given the ‘extremist’ label. Lukashenko is not averse to using social media himself in what has been called his “hybrid war” against the EU, apparently in revenge for sanctions against him and his despotic regime. It was how he urged tens of thousands of mainly Iraqi Kurd refugees to come to his country for an “easy” access into the EU by crossing, “unchallenged”, into Poland or Lithuania. The access proved far harder than Lukashenko had promised but Belarusian authorities confiscated the migrants’ mobile phones, leaving the media struggling to keep up.

Russia itself is a major user of social media, but by no means the biggest, ranking sixth in the world, behind China, India, the United States, Brazil and Japan. However, Russians may rank fairly low in terms of overall use but they spend a lot of time on-line. According to the Translate Media website, of the 3 hours and 34 minutes ordinary Russians spend on average online every day, most of the time is spent reading news. VKontakte (VK) is Russia’s biggest social media site, with Moi Mir and Odnoklassniki (OK.ru) not far behind. Twitter and YouTube are also popular, but LinkedIn is banned.

Freedom House reports on its own website that: “According to the Levada Center, a non-governmental research organization, the overall internet penetration rate reached 76 percent by the fourth quarter of 2019, when the proportion of Russians who used the internet daily or at least several times a week was about 65 percent.” The switch to 5G networks has proved difficult because the frequencies required for it to run are controlled and used by the Russian military.

A SLEEPING GIANT WAKES UP

If you’re looking for a fair and free internet for social media, you can forget China. Freedom House again reports that: “Conditions for internet users in China remained profoundly oppressive and confirmed the country’s status as the world’s worst abuser of internet freedom for the seventh consecutive year.” During the monitoring period, Freedom House found that: “authorities censored calls for an independent investigation into the origins of the COVID-19 pandemic and criticism of Chinese-produced vaccines. Ordinary users continued to face severe legal repercussions for activities like sharing news stories, talking about their religious beliefs, or communicating with family members and others overseas.” As Mao Zedong once said, “Communism is not love. It is a hammer which we use to crush the enemy.” It’s doubtful, of course, if he would recognise Xi Jinping’s regime as ‘Communist’ at all. He could be quite ambivalent, of course, even suggesting that variety of thinking could be useful, saying: “Letting a hundred flowers blossom and a hundred schools of thought contend is the policy for promoting progress in the arts and sciences and a flourishing Socialist culture in our land.” He did not really approve of artistic activities, though, and apparently hated his own poetry. When told by the journalist Robert Payne after a dinner during the Long March that students at one university knew his poem ‘The Snow’ by heart, he smiled in disbelief and said: “They have no business wasting their time with these poems.” He may have felt they shouldn’t waste their time on the internet either, but we’ll never know.

The United States may favour poetry more (perhaps not the poetry of Mao Zedong) but a lot of Americans have demonstrated over and over again that they favour wealth. As the American philosopher, historian and social critic Noam Chomsky wrote: “Concentration of wealth yields concentration of political power. And concentration of political power gives rise to legislation that increases and accelerates the cycle.” That certainly seems to form the basis of the business model most loved by the world’s social media companies. The New York Post reported, towards the end of last year, that Facebook had admitted that its “fact checks” on what its users can access are no more than “opinion”. In fact, on science issues such as Covid-19, climate change and air pollution, Facebook defers to Science Feedback, a worldwide group of scientists who check the supposed facts. Not all of those who have posted content that has been subsequently blocked agree with Science Feedback’s criteria or judgements, and some have complained to Facebook about not being allowed to post. Facebook, it seems, then refers them to Science Feedback, effectively hiding behind the independent fact-checkers. This has provoked complaints from those denied access to the web, especially over the issue of whether or not the SARS-CoV-2 virus had originally escaped from a laboratory in Wuhan. Science Feedback recommended blocking the article, but without pointing out that one of the contributing expert groups behind the judgement, EcoHealth, had funded the Wuhan lab. The deeper one digs into social media and its relative fairness, let alone its accuracy and reliability, the murkier it all becomes. As the New York Post put it: “The fact-check industry is funded by liberal moguls such as George Soros, government-funded non-profits and the tech giants themselves.

The checkers are not the unbiased arbiters of truth; they are useful distractions, groups Facebook can use to absolve itself of responsibility.” It also added, somewhat gratuitously, the expression: “Free speech be damned.” With all this talk of fairness and absence of bias, we should, perhaps, recall that since the NYPost was bought by Rupert Murdoch in 1976 it has become a paper of the somewhat illiberal right.

Worldwide, then, where do we stand with social media? According to the Surfshark website, last year was better than the one that preceded it. 2021 saw 19 social media shutdowns, down from 29 the previous year. Most cases of censorship happened during political events. Furthermore – and this may come as a surprise – Africa is the world’s most censored continent. At the beginning of that year, Uganda imposed an internet blackout to coincide with its presidential election. I must admit to disappointment with Uganda. Many years ago I was there with a camera crew to cover a conference under the Lomé Convention, which brought together the EU and the African, Caribbean and Pacific group of countries (ACP). While I was there I interviewed the President, Yoweri Museveni, in the garden of the presidential palace. He came across as a reasonable man, amiable, highly intelligent and keen to modernise his country. A month or so later, during an official visit to the European Parliament in Strasbourg, he recognised me in the corridor and stopped to greet me and have a chat. It seemed warm and genuine, and I believed in his good intentions for his very beautiful country. Since then, his apparent determination to cling to power at virtually any price has seen some very strange figures rise to positions of prominence and, indeed, influence in the country, which saddens me.

In his book “Speech Police – The Global Struggle to Govern the Internet”, author David Kaye points out how much social media has changed: “As Bill Clinton famously said about China’s hope to control the internet, ‘Good luck! That’s sort of like trying to nail Jell-O to the wall.’

But the contemporary internet is nothing like Jell-O. It facilitates control by companies and governments: censorship and abuse, representation and disinformation.” Kaye, who is the United Nations Special rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression, makes the point that the internet was designed to be a kind of free-speech paradise, but a lot of the material on it turned out to incite violence, spread untruth and promote hate. I’m not really sure that it was ‘designed’ to be anything other than a simple way to communicate and publicize people’s views. Napoleon Bonaparte famously said of China: “There lies a sleeping giant. Let him sleep! For when he wakes, he will shake the world.” Considering that was written in 1821, it shows amazing perspicacity on the part of the great French general. The world has certainly been shaken and now Xi Jinping is determined to ensure that his part of it isn’t shaken any further.

Closing the internet, for whatever reason and for however long, is not a cost-free exercise. Business Insider reports that, according to Top10VPN, in 2021 internet shutdowns cost the global economy $5.5-billion (€4.84-billion). Worst hit was Myanmar, which lost an estimated $2.8-billion (€2.46-billion) because of shut-downs. It’s not money this crisis-hit country can afford to lose. The Asian Development Bank expects last year to show an economic contraction for Myanmar of 18.4%. For authoritarian governments, retaining personal power remains of much greater importance than saving the population from poverty and hunger. With some countries resorting to draconian measures to clamp down on on-line dissent, there would seem to be a stark choice between an open and free internet where free speech reigns supreme and a heavily censored and closely-policed means of communication whose participants could end up in jail or worse if they post a derogatory comment. Interestingly, David Kaye quotes a European Commission official as being the man to ask the most vital question.

Robert Viola, who headed the Commission’s division responsible for communications networks, content, and technology (known in Brussels as DG-CONNECT, with DG standing for Directorate-General) met Kaye at his Brussels office in 2018 and started out with the most essential and obvious question: “Who is in charge?” It’s a fundamental question, but one to which there is no clear answer. As Kaye points out, it means asking such questions as “who ensures the protection of individual rights on the internet? Who makes the rules that govern online expression? Who enforces them? Who adjudicates disputes concerning their enforcement? The companies? National governments? The European Commission? Some combination of them?” Nobody has so far come up with an answer that meets with universal agreement. The media giants have shown they’re not to be trusted if it comes to a choice between responsibility and profit.

In this report, published by the European Commission, an international team of experts takes a behavioural science approach to investigate the impact of online platforms on political behaviour.

Governments are certainly not to be trusted when most politicians would say virtually anything to get re-elected, however untruthful. Not the Commission because a lot of citizens don’t trust the EU, either. Donald Trump’s most ardent supporters have used it to incite violence against an elected government because they didn’t like the result of an election. Unrest against various dictators has been urged and has caused violent clashes and deaths. Belarus has used it to lure unsuspecting migrants to an icy forest in winter, just to destabilise the EU. It is a huge reservoir of possibilities, good and bad. As Kaye points out, governments regulate internet content while tech companies moderate it. But if the websites themselves are the gatekeepers or frontier guards on the road to information, they have to be fully transparent and accountable. Is there a way to ensure that? Clearly not; at least, not yet. Even the more prudish governments have found it virtually impossible to curtail such activity as prostitution and on-line pornography, let alone political discontent. It’s especially difficult because we don’t all share the same values when it comes to decency and morality (which, perhaps, is just as well), let alone our political leanings. We just have to celebrate our differences and the wide range of the views we hold. Regardless of what we find on-line and whether or not others agree or disagree with us, I refer you to that old French saying: “Vive la Différence!”