“In the centre of our movement stands the idea of a Charter of Human Rights, guarded by freedom and sustained by law.” Those words were spoken in 1948 by Winston Churchill, Britain’s wartime leader but by then no longer prime minister.

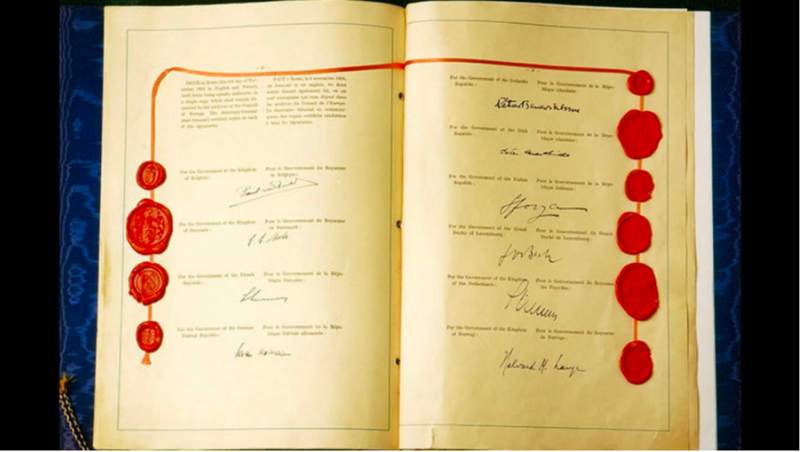

Signatories to the European Convention on Human Rights

Signatories to the European Convention on Human Rights

The occasion was a gathering of more than 750 delegates from civil society organisations, business, academia, religious groups, trades unions and leading politicians from all over Europe. They met in the Hall of Knights at the Europa Congress in The Hague in May 1948. There had been discussions about a legal commitment to protect people’s rights since the early years of the Second World War, when it was clear that a great many people’s rights were being trampled on. The idea throughout had been to prevent governments from dehumanising people and abusing their rights. The situation that led to the war must never be allowed to arise again. Apart from Churchill, the event was also attended by, among others, the young François Mitterrand and the German Chancellor, Konrad Adenauer.

Konrad Adenauer © Wikipedia

Konrad Adenauer © Wikipedia

It was at that gathering that a list of the rights to be protected was drawn up, including some articles taken from the United Nations’ own Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Throughout the summer of 1949 more than a hundred parliamentarians came together to draft the charter. Britain was the first country to ratify it in March 1951. That makes it somewhat ironic that the UK’s present Conservative government has been talking about withdrawing from it. Michael Gove, the UK government’s Minister for the Cabinet Office, has said he favours a national bill of rights instead, in a concern over sovereignty. The idea was first raised in 2016 by former prime minister Theresa May when she was Home Secretary. Well, I suppose 1951 is a long time ago – before most members of today’s parliament were born – and memories can fade. Still, the idea that an international treaty can be ‘too international’ seems somewhat bizarre, especially when your country helped draft it in the first place.

It’s a clear fact that rights, if they’re to be protected, need to be established in law. The 18th to 19th century English philosopher and jurist Jeremy Bentham wrote that “right is a child of law”. He had no time for the idea of natural rights that stem from us simply being human. “From real laws come real rights,” he wrote. “But from imaginary laws, from laws of nature, fancied and invented by poets, rhetoricians and dealers in moral and intellectual poisons, come imaginary rights, a bastard brood of monsters.” It was something of a hobby-horse with Bentham. “Natural rights is simple nonsense,” he also wrote, “Natural and imprescriptible rights, rhetorical nonsense – nonsense upon stilts.” The trick for those politicians meeting in 1949 was to encode the rights that mattered within an enforceable legal framework. They succeeded, and the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) came into effect on the 3rd September 1953.

“It was intended to be a simple, flexible roundup of universal rights, whose meaning could grow and adapt to society’s changing needs over time,” says Amnesty International, a campaign organisation for human rights. “Not only were ordinary people to be protected from abuse by the state, but duties were to be placed on those states to protect individuals. It has been hugely important in raising standards and increasing awareness of human rights across CoE (Council of Europe) member states, and beyond.” But if you want to have legal judgements on rights issues, you need not only the necessary laws but also a court in which to enforce them and judges to adjudicate. That came in 1959 when the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) was set up in Strasbourg. The court is there not only to safeguard the ECHR but to create the required case law and also to allow people who believe their rights have been denied to have their cases heard in a neutral setting. Judgements made by the court are legally binding and countries against which successful cases have been brought are legally obliged to abide by them.

The European Court of Human Rights is an international court established in 1959 by the Council of Europe © Council of Europe

MANY ACHIEVEMENTS

So what has the ECHR achieved? It has led to the decriminalisation of male homosexual acts, for one thing. Jeff Dudgeon, a shipping clerk in Northern Ireland who was gay, was arrested and questioned for several hours by the Royal Ulster Constabulary in 1975 for an act that was legal in England and Wales (and soon would be in Scotland) but not in Northern Ireland at that time. The case was admitted for a hearing at the Strasbourg court in 1981 and Dudgeon won. It led to a change in the law in Northern Ireland in 1982 and the verdict was cited as an example in a similar case brought by David Norris against the government of the Republic of Ireland in 1988. Again, the law was changed. Dudgeon’s case against the United Kingdom was also used by Justice Anthony Kennedy in a case brought in 2003 in the United States: Lawrence v. Texas. The US Supreme Court decision found that anti-sodomy laws in the remaining 14 states were unconstitutional, while Alexandros Modinos successfully brought a case against the government of Cyprus, again citing the Dudgeon case. And all because one mistreated gay man had the courage to enlist the help of the European Court to uphold his rights.

Jeff Dudgeon © Queerarchive.net

Jeff Dudgeon © Queerarchive.net

According to the blog of the European Journal of International Law, the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) has had an influence for good far outside Europe’s borders. “The innovative doctrines and principles pioneered by judges in Strasbourg are alive and well in other human rights systems. Interpretive tools such as the evolutionary nature of human rights, the presumption that rights must be practical and effective, the creative and strategic approach to remedies, and cross-fertilization of legal norms are commonplace in the case law of all regional and sub-regional courts. For example, Inter-American judges have applied these doctrines in several types of cases, including the obligation to investigate, prosecute and punish the perpetrators of past human rights violations, the prohibition of amnesty for such violations, the rights of LGBT persons, and affirmative measures to combat violence against women.” So writes Laurence R. Helfer, a Professor of Law and Co-director of the Center for International and Comparative Law at Duke University. Professor Helfer admits though that while most western and developed world jurisdictions follow ECtHR judgements fairly closely, safe in the knowledge that the Convention has widespread popular support, courts in Africa and other developing countries are sometimes more circumspect to reflect widely-held moral and religious beliefs in the country concerned. It’s also worth noting that notwithstanding the protection afforded to women by the Istanbul Convention, Poland is on the verge of withdrawing from it, so, ironically, is Turkey, having never fully implemented it.

Pınar Gültekin © milliyet.com

Pınar Gültekin © milliyet.com

This follows the after the brutal murder of 27 year old Pınar Gültekin, which has prompted protests across Turkey, demanding better protection for women. Slovakian parliamentarians refused to ratify the Convention, stating that “It’s in conflict with the constitutional definition of marriage, which is worded as a union between a man and a woman.” It sounds as if they believe a man has a right to beat his wife. I have seen the dreadful effect gender violence has and interviewed several of its many, many victims. One woman I spoke to tried to leave her violent husband several times, but he dragged her back, on one occasion by her hair, saying she belonged to him; she was his possession. Eventually, the police intervened, and he was sent to prison, apparently still not understanding why he wasn’t allowed to beat her. “Lots of women are frightened that they’ll not be believed, and lots of women who come through our door feel it’s their fault,” I was told by Julie Robinson, who runs the Options Programme for victims of domestic violence on Tyneside, in the North East of England. Why do men do it? “Power and control,” she explained. “He was a perfect gentleman when I met him,” one victim told me. But then after she had put up with him controlling her and his regular bouts of violence, one day he punched her in the head very hard. “Then he punched me from the kitchen, from the dining room, and all the way back, in front of his friend, and I was unrecognisable.” There is no moral case whatsoever, however dressed up, that excuses withdrawal from the Istanbul Convention, nor a refusal to sign up to it, unless you believe that men have a right to beat up their female partners. Sadly, some men do, and it seems some politicians agree with them.

How does the Convention work? First of all, the applicant has to have exhausted all the channels provided by their own country’s legal system. When the case reaches the ECtHR, the court first contacts the government concerned and tries to arrange a ‘friendly’ settlement. If that fails, the government concerned is given twelve weeks to respond to the allegation. The applicant is then given time to respond to whatever the government says. The admissibility of the case is then decided by a single judge, a committee of three judges or a chamber of seven judges before it’s deemed ready to go to a Grand Chamber of seventeen judges.

The ECHR Grand Chamber of seventeen judges © echr.coe.int

The ECHR Grand Chamber of seventeen judges © echr.coe.int

Not all cases get that far, and many are settled earlier and more quickly. But if the small committee, the chamber or the Grand Chamber agree that there is a case to answer, their verdict is referred to the Committee of Ministers (CoM). The CoM is made up of representatives of the governments of the 47 Member States, assisted by the Department for the Execution of Judgments of the Court. It’s their job to carry out the judgement. It’s not always easy: some governments occasionally insist that they are right, and the Court is wrong. However, the states have a legal obligation to remedy the violations found but enjoy a ‘margin of appreciation’ as regards the means to be used. The measures to be taken are, in principle, identified by the state concerned, under the supervision of the Committee of Ministers. The Court can assist the execution process, in particular through the pilot-judgment procedure (used in case of major structural problems). Examples of the general measures that have been agreed include the introduction of effective remedies against excessive length of court proceedings; the removal of discrimination against children born out of wedlock (such as in inheritance matters); the adoption of legislation to prevent arbitrary recourse to telephone-tapping; and the lifting of undue restrictions on journalists’ freedom of expression.

STILL WORKING AFTER 70 YEARS

The Convention is still regularly raised at the meetings of the Council of Europe’s Parliamentary Assembly (PACE). The Assembly is made up of elected parliamentarians from all of the Council’s 47 member states. Nobody has a veto and any relevant topic can be raised. These meetings are normally held four times a year, but the COVID-19 pandemic has thrown that schedule into disarray. For instance, at the last session before the coronavirus made travel all but impossible, in January 2020, a resolution was adopted to try to oblige countries whose citizens had gone to fight for ISIS to allow the children of those people to travel home, while retaining their citizenship.

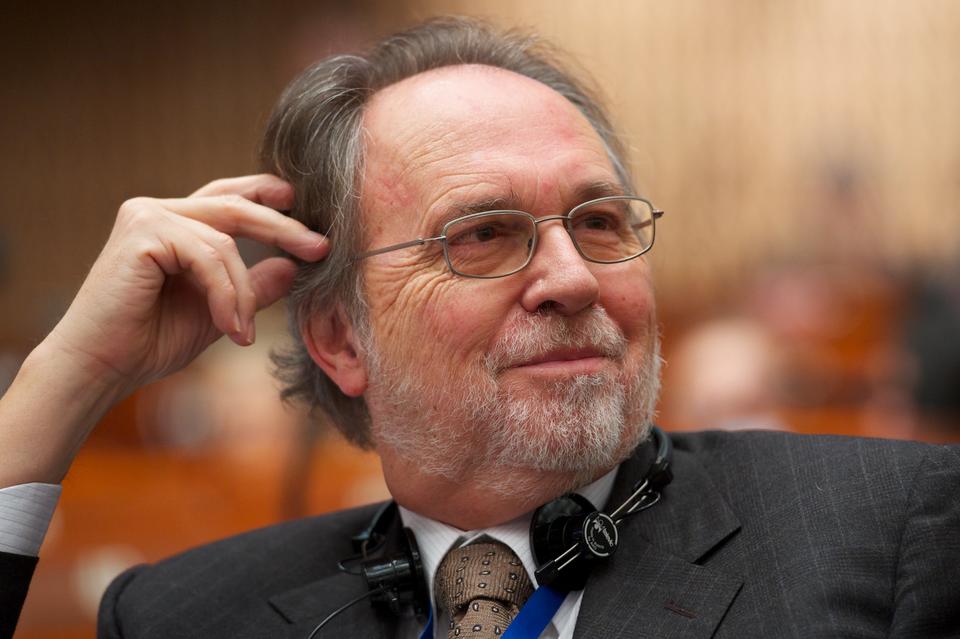

Stefan Schennach © Wikicommons

Stefan Schennach © Wikicommons

The report, by Austrian Socialist, was passed overwhelmingly, based on Article 8 of the ECHR, which states that “Everyone Stefan Schennach has the right to respect for his private and family life, his home and his correspondence”. Schennach told the Assembly that “most of these children have European parents. Young girls, who went there the age of 15 or 16, have ended up there. We don’t know why. We don’t know what was happening in the social lives, how modern it was, and not all were Islamic, by the way. And then they got babies, sometimes from different men.” The assembly agreed and it’s possible that the issue could end up at the ECtHR, if one of the young women or their children brings a case. Ironically, ISIS – or Daesh to use its other name – had no respect at all for human rights or even human lives, but that doesn’t alter the protection provided by the ECHR to its fighters’ offspring. Babies and children have no control over where they were born or their parents’ beliefs.

PACE also debated the secret transfers and illegal detentions involved in what were called ‘extraordinary renditions’. As explained by the Open Society Justice Initiative, Extraordinary rendition is the transfer – without legal process – of a detainee to the custody of a foreign government for purposes of detention and interrogation. People – many of them totally innocent and seized by mistake – were snatched from the street and taken off to secret detention camps in Poland, Estonia and Romania, among other places, where they were subjected to what the Americans called ‘enhanced interrogation’ – that’s torture, to you and me. The initiative was begun after the 9-11 attacks on the United States, but a lot of mistakes of identification were made, with people totally unconnected from terrorism caught up because they looked similar or shared a common name.

Swiss Senator Dick Marty © Amicale-coe

That’s why a resolution was drawn up by Swiss Liberal Senator Dick Marty, under Article 5 of the Convention, the Right to Liberty and Security, in June 2007. “To begin with,” Senator Marty told me, “it’s worth noting that an enormous majority of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe adopted the resolution. We should also recall that the resolution was based on a number of judgements by the European Court of Human Rights, which had passed judgements condemning quite a few member states of the Council of Europe for violations of the European Convention on Human Rights.” Those the CIA judged to have been involved in terrorism were eventually transferred to Guantanamo Bay. Five of those accused of involvement in the 9-11 attacks have been put on trial in the prison camp, although their lawyers can only contact them by video link and hardly at all during the COVID-19 pandemic. Dutch member René van der Linden, a member of the centre-right EPP/CD group, who was President of the Assembly at the time, told me “I believe the Marty Report is one of the most important we have had in the last 20 or 25 years because it was paying attention to all the countries of Parliamentary Assembly and also in the United States it got a lot of publicity.” Not always favorable publicity in that case, but it opened people’s eyes. In the Assembly itself, some countries’ delegates opposed it, but Marty was not surprised by that. “They were against it (the report) because they wanted to cover up their activities that were against the law and were therefore criminal activities.” He also thinks that extraordinary renditions may still take place. “It’s hard to be definitive, but I think the secret detentions continue, but that the detained are no longer held in Europe.” It’s a victory of sorts and it shook the world at the time.

SINKING IN DISINTEREST

Then there was the issue of refugees crossing the Mediterranean from the Libyan coast in inadequate boats and not receiving help from other vessels. In April 2012, it was the subject of a resolution passed overwhelmingly by the Parliamentary Assembly under Article 2, the Right to Life.

Refugees crossing the Mediterranean from the Libyan coast © Massimo Sestini

Refugees crossing the Mediterranean from the Libyan coast © Massimo Sestini

Then there was the issue of refugees crossing the Mediterranean from the Libyan coast in inadequate boats and not receiving help from other vessels. In April 2012, it was the subject of a resolution passed overwhelmingly by the Parliamentary Assembly under Article 2, the Right to Life. The member who drafted it was a Dutch Socialist Tineke Strik (now a senator for the Green Links party), who was alarmed by a story about 72 people who had been in a rubber dinghy in the Mediterranean for fifteen days. “They had cried out for help to many vessels, people that they saw around,” she told me, “and no-one came to the rescue in order to help them, in order to survive, and take them on board or disembark them in a country.” It’s worth remembering that the sea off Libya was considered a war zone at the time, but that doesn’t alter the law of the sea nor the obligation of a ship’s master to aid vessels in distress and their passengers. “So, for 15 days they drifted in the Mediterranean Sea,” Strik told me, “and during those 15 days, sixty-three of them died. “They died of starvation and did not manage to survive. Only eleven of them managed, by drifting back to the Libyan coast, because they departed from Libya, a Libya that was at war at that time. There were bombardments from NATO and they really had to flee the country in the end. Because no-one helped them, they found themselves back at the Libyan coast, by the shore, where they were immediately taken into detention again and two of them died, because they were completely weak.” They were eventually released several months later after someone on the outside paid a bribe, and the survivors managed to escape from Libya again.

Dutch member of the Senate for GreenLeft Tineke Strik © groenlinks.nl

Strik’s report centred on the failure of other countries and vessels to come to their aid at a time when the Mediterranean was full of military vessels. Strik carried out an investigation and interviewed the survivors. “I found out that in those few weeks there were military vessels in the neighbourhood. There was also a helicopter, a military helicopter, that flew very low above them. They gave them some water and some biscuits, but then they went away and never came back. In the end, even when almost everyone was dead, when they held up a baby who had died and showed they didn’t have any water, there was still a very big military vessel coming in their vicinity. The sailors had binoculars, so they really were looking at them, with cameras, and in the end they still sailed away.” In fact, ships’ masters face a difficulty when they come across migrants in distress. “Unseaworthy boats are often encountered, heavily overloaded, in serious peril and in need of rescue,” says the legal firm Norton Rose Fulbright. “Most mariners will not hesitate to ‘do the right thing’ and conduct a rescue. Indeed, the law of the sea requires them to do so (my emphasis). However, it is once the rescue is conducted and migrants are onboard that issues might arise. In the face of unprecedented levels of migration, EU states are becoming less welcoming.” Some are sending migrants back to their port of origin, which is called refoulment and is, again, against international law.

Strik never found out to which country the helicopter and large naval vessels had belonged; those responsible for the deaths of the migrants remain unpunished, but as she says of her report “nevertheless it raised a very lively and urgent debate on how to act in these types of situation.” “Our great regret,” said Jean-Claude Mignon, a French EPP/CD member who was president of the Assembly at the time, “is that the European Union did not quickly respond. It’s true that the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe did not have the same powers as the European Union to take action about it.” No-one did, of course, and migration remains a divisive issue. Strik admitted it was a ‘who-dunnit’ without the guilty party ever being identified. I was once told by the French politician and physician Bernard Kouchner, co-founder of Médicines sans Frontières, that the only way to stop unwanted migration into Europe is to raise living standards in the countries from which the refugees come. That would remove the incentive to risk life and limb to get to what they hope will be a better life for them and their families.

NON-DISCRIMINATION: VIOLENCE IS VIOLENCE

The rights conferred by the ECHR are, of course, universal, and not dependant on age, gender or ethnicity. That is confirmed in Article 14: “The enjoyment of the rights and freedoms set forth in this Convention shall be secured without discrimination on any ground such as sex, race, colour, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, association with a national minority, property, birth or other status.”

Fatima, 7, sits on a bed in her home in Afar region, Ethiopia. She was subjected to FGM/C when she was 1 year old © Unicef / Holt

Fatima, 7, sits on a bed in her home in Afar region, Ethiopia. She was subjected to FGM/C when she was 1 year old © Unicef / Holt

That’s why, in October 2016, a resolution was adopted on female genital mutilation (FGM), which is much more common than most of us would choose to believe. It’s been estimated that 500,000 women and girls are living in the European Union who have undergone FGM, and a further estimated 180,000 are at risk of it, the figure is thought to be 200-million. FGM is a terrible example of violence against women and a very serious violation of human rights. Béatrice Fresko-Rolfo, a Liberal member the Monaco Parliament, was General Rapporteur on violence against women in the Parliamentary Assembly, and she was the author of the report on “Female Genital Mutilation in Europe”. “The figures are alarming,” she said, “and reveal, if indeed evidence were necessary, that we are directly affected. We must acknowledge that this practice takes place worldwide and must take action to ensure prevention, protection and appropriate punishment, and to remedy and deal effectively with the long-term consequences on the lives of these women.”

Béatrice Fresko-Rolfo, a Liberal member the Monaco Parliament © Wikipedia

Before anyone raises the notion that it’s a practice required by religion, that is not true, although the practice is deeply rooted in tradition. “FGM is one of the harmful traditional practices that is widely practiced in at least 28 African countries, parts of the Middle East, pockets of some communities in Australia, the Far East and the immigrant population in Europe and the Americas originating from FGM practising countries,” writes Dr. Ashenafi Moges on the African-Women.org website. “The FGM operation which is painful by itself has immediate and long-term consequences on the health and psychology of women and girl-children. Despite all the negative consequences of FGM, at least 2 million infants, girl-children and women undergo the operation every year (that is about 6,000 per day or one in every 15 seconds).” The Council of Europe cannot prevent the practice worldwide – it is almost universal in sub-Saharan Africa – but it can try to clamp down on FGM in Europe itself. “I hope the report will have an impact,” Mme. Fresko-Rolfo told me. “I hope the report will convince people that it exists.” She says: “it may not be the requirement of any religion, but the practice is rooted in the culture and beliefs of the local community.” Fresko-Rolfo’s resolution stresses that FGM is an act of violence against women and children and a flagrant violation of human rights. It also points out that as most of the victims are extremely young (from a matter of a few days old to 7 or 8 years of age) the practice also constitutes a violation of children’s rights. The report states that prevention must lie at the heart of attempts at eradication and it must involve all those involved, whether practising communities, social and educational services, the police, the justice system or health care professionals. Recognising the practice as violence against women and children and running public awareness campaigns is about as much as the European nations can do and to change hearts and minds takes time.

MURDER MOST FOUL

In June 2019, a report by Dutch EPP/CD member Pieter Omtzigt drew attention to the murder in Malta of the journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia, after she had exposed widespread corruption in government and elsewhere. Caruana Galizia was murdered with a car bomb just outside her Bidnija home on 16 October 2017. The report on it was brought to the Assembly under Article 10 of the Convention: “Everyone has the right to freedom of expression.

Daphne Caruana Galizia was killed in a car bomb in Bidnija © Malta Times

Daphne Caruana Galizia was killed in a car bomb in Bidnija © Malta Times

This right shall include freedom to hold opinions and to receive and impart information and ideas without interference by public authority and regardless of frontiers.” Caruana Galizia was the one who exposed the so-called Panama Papers, showing graft and corruption at the highest level, which drew vicious opposition that resulted in her bank account being frozen and several libel cases. The murder inquiry has always been a convoluted affair, as the latest report (at the time of writing) from the Malta Today newspaper reveals: “Three men, George Degiorgio, Alfred Degiorgio and Vince Muscat, have been charged with carrying out the assassination, while Yorgen Fenech is charged with masterminding the murder. Melvin Theuma, who acted as a middleman between Fenech and the three executors of the crime, was granted a presidential pardon last year to tell all. Theuma is currently being treated in hospital for serious wounds he sustained, which the police said were self-inflicted.” A man charged with murdering Daphne Caruana Galizia has accused government of sitting on his request for a presidential pardon in return for information on the assassination plot and several other unsolved crimes. Meanwhile Muscat, one of three men who planted and detonated the bomb, said he would reveal all and provide information on previously unmentioned parties in order to help investigators join the dots in the complex murder plot in return for a pardon. Under Maltese law, libel actions brought against Caruana Galizia were inherited by her surviving family. The Council of Europe’s Human Rights Ombudsman, Dunja Mijatović has requested that they should be dropped.

Omtzigt had a difficult task to get his resolution accepted, but it was. “It was one of the organs of change in Malta,” he told me. It didn’t make him a popular figure on the island. “The government of Malta and some of the Maltese press have not put forward a picture of me as being the most trustworthy person on Earth.”

Pieter Omtzigt © pace.coe.int

Pieter Omtzigt © pace.coe.int

The problems Omtzigt faced help to underline the courage of Caruana Galizia. The car in which she died was a rental; by freezing her bank account the government stopped her from accessing her own vehicle. “The first thing we asked for,” Omtzigt explained, “was that an independent inquiry be set up, and yes, it was a bit of a battle, but the independent inquiry was set up and of course there was a battle on its terms of references, but after that battle on the terms of references, it was pretty OK.” In his research before writing the report, Omtzigt also faced obstructions. “They tabled a motion of no confidence in me, which had never happened in the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe. Someone connected there changed my Wikipedia page and put some nonsense on that page. Oh, yeah! The pressure was applied.” Maltese members tried to prevent the report mentioning murder “as murder has not been proved”. Omtzigt pointed out that it’s hard to classify a car bomb as an accident or an act of God. It could be classed as an act of the ungodly, perhaps, I think. Omtzigt is not sure, of course, that all will turn out well, but at least for Malta the process of self-examination is underway, along with a growing realisation that the world is watching. The president of the Assembly at the time, Swiss Socialist Liliane Maury-Pasquier, believes that Omtzigt’s report was an important achievement. “The prime minister has been replaced, got rid of, and Malta now has an independent commission of inquiry.” She told me the procedure had been good for Malta and good for democracy.

And so the world changes, a little bit at a time and in baby-steps. Looking across Europe as a whole, it would be true to say that just as in some places there are signs of progress, elsewhere neo-nationalism and self-interest are becoming increasingly entrenched, with democracy itself being under threat here and there. Some you win, some you lose, as the saying goes. The trick is to win more than you lose, something at which the European Convention on Human Rights has proved very useful. After seven decades, it’s still possible for it to shake up undemocratic or corrupt governments. In Churchill’s words, we still need to be “guarded by freedom and sustained by law.”

Jim Gibbons

Click here to read the 2020 August edition of Europe Diplomatic Magazine