© Oxford University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust

How did this come about? Britain’s flagship National Health Service (NHS) is very ill and getting worse. We haveseen ambulances queuing up outside Accident and Emergency (A&E) departments with their patients inside because the A&E department itself is full to overflowing and has no beds available. In other instances, we have had the unedifying sight of patients being admitted to hospital but then being left on trolleys in corridors for hours because no beds are free for them in the relevant wards. It gets worse as patients get older, too: more than 100,000 elderly patients are ready to be discharged but there is nowhere for them to go, so they remain, taking up space that could be needed for real emergencies. It’s known as “bed-blocking” and it happens a lot. It’s one of the reasons why surgical operations that have been scheduled are often cancelled, quite frequently at the very last minute, because there are no operating theatres available and too few surgical staff. It’s not always like this, of course. When, on separate occasions, my wife and I needed emergency help an ambulance was at our door within fifteen minutes and we were driven to hospital, receiving treatment in A&E immediately, despite living in a village some distance from the nearest town. When it works, it works extremely well.

I have a deep affection for Britain’s ground-breaking National Health Service, which is just three months younger than I am. It came into being on 5 July 1948. It was a concept of Britain’s post-war Labour government and the nation’s doctors – general practitioners – were totally opposed to it from the start. The British Medical Association, which in the UK is the doctors’ trade union, opposed the plan and in the early days its secretary, Dr. Charles Hill, was accused of attempting to strangle it at birth with a campaign of sabotage, although even right-leaning newspapers and periodicals did not support him.

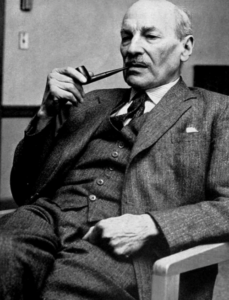

Much of the hard spadework in setting up the system fell to Aneurin “Nye” Bevan, a Welsh Labour MP, serving as Britain’s Minister of Health. He was a tough-talking man from the Welsh valleys, the son of a coal miner, and he had played a part in Britain’s General Strike in 1926. In setting up the NHS, he often complained that he didn’t get as much support as he would have liked from either his cabinet colleagues or from the prime minister at the time, Clement (Clem) Attlee. Bevan’s determination saw it through, however. The doctors, according to John Bew in his fascinating biography of Attlee, “Citizen Clem”, were not on Bevan’s side. “A majority of GPs,” he wrote, “refused to cooperate with the scheme – demanding freedom to practise in the area of their own choosing, more control over their salaries, and other employment rights – until the last few months before it came into being.” Bew wrote that Attlee admired “Bevan’s idealism and force of character and the crucial role he played in the formation of the National Health Service.” Bevan had created something that won worldwide admiration and became a model that some other countries copied.

Bevan warned the British people that they would not see overnight improvements. There were no additional resources available so soon after the Second World War, and no additional doctors or nurses queuing to get involved. It did change the way people paid for their health care: instead of paying for their treatment at the point of delivery, fees were paid by taxpayers, making treatment free for the patient. In that way, accessibility was immediately and enormously improved. The Times newspaper wrote at the time that “the masses” had joined the middle class. It meant rich and poor alike were treated in the same way.

Of course, the existence of the NHS did not prevent terrible diseases from occurring. Poliomyelitis, for instance, normally referred to simply as polio, became a terrifying reality in the 1950s. Strangely, it spread quickly because of improved hygiene. It’s a viral infection and is passed on by infected water, among other things. It had become so common in previous centuries that mothers developed a kind of immunity which they passed on to their children. But polio has two stages, and without maternally inherited immunity, it can move on from having the mild influenza-like symptoms of stage 1 to a much more aggressive stage with an agonising headache, nausea, fever and muscle ache that can turn in 48 hours into paralysis. I remember children at my school with elder siblings who were forced to use a wheelchair.

Eventually a vaccine was developed and in the UK’s case administered by the NHS. Other diseases that were horribly common back then included scarlet fever and diphtheria. Scarlet fever was most common among children under the age of 10. It was highly infectious, and it was caused by bacterium called Streptococcus pyogenes, the same virus that can also cause impetigo. Its symptoms include a sore throat and a rash, and it can sometimes be confused with measles. Then there’s diphtheria, which is mercifully rare in the UK these days because children have been routinely vaccinated against it since the 1940s. Diphtheria is a highly contagious bacterial infection, spread through contact with an infected person and by coughs and sneezes. Outbreaks of all three – polio, scarlet fever and diphtheria – were a challenge to the new NHS back then. We have, however, had the arrival of coronavirus disease, 2019, normally shortened to COVID 19, a virus which causes severe acute respiratory syndrome. Supposedly originating in China , in our closely-connected world, it quickly spread across borders. It is spread when someone with the virus breathes, speaks, coughs or sneezes. They release small droplets containing the virus. With care, and with sensible people taking sensible precautions the pandemic is being mainly contained. Even so, not everyone in British politics is convinced, with Jeremy Hunt (currently the Chancellor of the Exchequer – finance minister – but previously Secretary of State for Health and Social Care) describing the response to the pandemic as “one of the worst public health failures in UK history”.

| THE FUNDING ILLNESS

These days, the biggest problem facing the NHS is funding. According to the Department for Health and Social Care in Britain, the planned spending for 2021-22 is £190.3-billion (€219.06-billion). In England, most of it is passed on to NHS England to cover the cost of improving health services.

In the same period, £33.8-billion (€38.91-billion) was to cover the cost of responding to the COVID-19 pandemic, including personal protective equipment (PPE) for staff, as well as vaccine and test-and-trace measures. The delivery of PPE equipment has not been without controversy, with massive contacts going to friends of government ministers. Experts have already warned that the extra money pledged is only around 50% of what is actually needed. There is never quite enough in the kitty. That’s why there is still an issue with health inequality, obesity, addiction and a workforce that is not in the most robust good health, despite all the television advertisements for devices “guaranteed to make you healthier”. A body called The King’s Fund monitors the NHS and reports on its success or otherwise. In one recent report it said: “The NHS will only be able to clear elective backlogs, deliver the NHS Long Term Plan and fight Covid-19 if it has the workforce it needs” (a workforce that is far broader than the tightly prescribed workforce commitments in the government’s manifesto). A recent international poll asked the public for the biggest problems facing their health care systems. The answer most frequently selected in Great Britain was ‘not enough staff’. The public aren’t wrong. The problem is finding enough money to bridge the shortfall. For instance, the NHS is not able to fund a drug that would help to protect some half a million people suffering from immunosuppression, when their bodies’ natural protective measures are ineffective and they are therefore vulnerable to COVID-19.

According to Jeremy Hunt, in his final report as chair of the Health and Social Care Committee, things are looking far from rosy. “Currently the profession is demoralised,” he warned. “GPs (general practitioners) are leaving almost as fast as they can be recruited, and patients are increasingly dissatisfied with level of access they receive.” He blames this situation on a simple shortage of GPs. He points out that in May of 2022, there were 27.5-million appointments in general practice, more than in 2019, but at the same time, the number of fully qualified, full-time GPs has dropped by almost 500. The result is that the GPs who remain are being forced to work harder, often dealing with a tangled mass of complicated cases. Hunt has come up with a range of possible measures to address the problems, such as limiting patient lists to, say, 2,500 people, reducing over the next 5 years; government action that would allow senior doctors to carry on working without attracting massive tax bills; better ways to fund deprived areas; and changing how general practice is managed, with less official interference. Now he’s become Chancellor, the answer to the question of whether or not these ideas can be funded will be down to him.

When the NHS was first set up its structure was three-fold: firstly, there were hospital services, organised into regional hospital boards, which took care of administration. Then came primary care, with doctors, dentists and opticians working as independent contractors, their fees paid by the government whilst not being on the government payroll. Finally came the community services, which included maternity, child welfare, vaccinations, and the ambulance service. A report prepared in 1980, rather appropriately called ‘the Black Report’, showed that despite the NHS being for everybody, poorer people had a shorter life expectancy and higher infant mortality rates. Clearly this was not the intention when Bevan set up the NHS. The NHS was always difficult to fund but never more so than now, with new and ever-more-expensive treatments for which the money must be found by the government, not the patient. And yet, with a shortage of nurses, the NHS has had to fall back on hiring “agency nurses” to bridge the gap. They stand in for the non-existent staff nurses, but are, of course, much more expensive. One Member of Parliament, who chairs the Conservative Policy Forum, has written to the Times newspaper to raise what are much the same policy issues as outlined in the Black Report more than 40 years ago: health inequality, poor housing standards, an unhealthy workforce, very long waiting lists for treatment, the low level of recruitment…the list goes on. The letter asks why these problems are being routinely and consistently ignored. Nothing much seems to have changed, although costs are, of course, rising. Britain’s nurses are proposing strike action in a bid to achieve the sorts of pay rise that the government says cannot be afforded. Recruiting agency nurses, however, inevitably costs more. It’s a conundrum.

In 2021, most members of the Royal College of Nursing – effectively the nurses’ trade union voted to reject a 3% pay rise. 89% said they’d be prepared to take action that falls short of a strike, but 54% expressed a willingness to go out on a real strike. Understandably, perhaps, nurses feel they cannot accept the government line that a pay increase for nurses is not affordable, when the agency nurses they’ve been hiring cost so much more. The spending of the Department for Health and Social Care in England (the four countries that make up the United Kingdom are assessed separately) is £33.8-billion (€38.97-billion) in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, that money including the cost of providing PPE equipment for staff, test and trace systems, programmes of vaccination and improving the process for the discharge of hospital patients. The vaccination system worked extremely efficiently; I have experienced it, of course, and was very impressed with the efficiency and kindliness of those involved.

The money also includes funding for delivering the government’s manifesto commitments. Making people healthier has never been a cheap option. There is even talk now of scrapping some of the targets imposed on health workers. In an interview for Sky Television, Health Secretary Steve Barclay spoke of “scaling back” some of those targets. Currently, hospital trusts can be penalised if diagnoses and referrals are not completed within certain time frames, which Mr. Barclay thinks may be too optimistic. “There is a place for targets,” he told his interviewer, “But if everything is a priority, nothing is.” He admitted the health service “is under huge pressure” but he placed the blame squarely on the COVID-19 pandemic. The National Schedule of NHS Costs suggests things are rather more complicated than that with community health care in England priced at £6,401,520,524 (€7,375,254,389) while accidents and emergencies cost £15,387,524 (€17,730,361). Planned spending in England for 2021-22 comes to £190.3-billion (€221.66-billion) in 2021/22, according to analysis of UK Treasury data by The King’s Fund. Keeping a country’s people well and treating them when they’re not is an expensive business. For the pen-pushers and bean-counters of Whitehall it means a massive headache. Aspirin, anyone (if we can afford one)

| CREAKING JOINTS

Some senior figures in government and the NHS are starting to raise questions about its sustainability. Certainly, keeping it in existence at all is a joint responsibility. After all, just as Nye Bevan intended, it belongs to every citizen of Britain. As Douglas Fraser, the Business and Economy Editor for BBC’s Scotland website wrote, “International comparison shows the NHS has relatively low management costs, but at a price of less flexibility, and some worse outcomes than comparable countries,” going on to add a truth that may not prove popular: “Not many in Britain admit it, but perhaps there are lessons to be learned from the way other systems are funded.” Fraser makes the point that the current system is “creaking”, as he puts it, and that: “there’s frustration within the top echelons of management that political leadership is not addressing the seriousness of the NHS’s problems.” Fraser argues that the spread of “radical ideas for reform” into the public domain shows that there’s a growing awareness of problems, for which, he says, “money can only be part of the solution.” In February 2022, Audit Scotland, a governmental body, reported that: “The NHS in Scotland is operating on an emergency footing and remains under severe pressure.” In this instance, most of the blame does rest with the infamous SARS-CoV-2 virus, the cause of the COVID-19 pandemic. There are still backlogs to address while budgets get ever tighter.

The economist Sir Andrew Dilnot said that pulling back on the promised reforms would be “deeply regrettable”, because urgent change is needed. Sir Andrew headed a review into the future funding of social care and proposed a cap on care funding – limiting how much can be paid for treatment, in other words. He says the government’s proposed reforms, while less generous than he had originally proposed, must go ahead as scheduled. These reforms are meant to include an £86,000 (€100,173.66) cap on personal care cost contributions, and “an expanded means test that is more generous than the existing one, to come into effect from October 2023.” Good health costs money. Lots of it. The UK’s Health and Care Levy is now estimated to raise £13-billion (€15-billion) a year on a UK-wide basis (rather than the £12-billion (€13.8-billion) a year as proposed in the Build Back Better project). This, plus updated forecasts of inflation, cost pressures and compensation for the NHS from additional employer costs of the levy, mean NHS England’s budget is now £2.5-billion (€2.88-billion) a year higher over the 2021 spending Review period (in cash terms) than was indicated in the Build Back Better announcements. This means that over this Spending Review period, NHS England’s resource spending will now rise by an average 3.8% every year. This projection includes the pre-announced £8-billion (€9.21-billion) to tackle elective backlogs over the next three years and a 30% increase in activity by 2024/25.

Funding overall for health services in England totals £190.3-billion ((€221.66-billion) in 2021-22, according to the Department of Health and Social Care, of which £136.1-billion (€156.67-billion) will be going to NHS England and NHS Improvement for spending on health services. What’s left is allocated to other national bodies to spend on things like public health (this includes grants given to local authorities), training and development of staff, and regulating the quality of care. It includes the £33.8-billion (€38.91-billion) for the COVID-19 pandemic. The funds come from general taxation. Unfortunately, the number of hospital beds available to patients has been steadily declining over the last three decades as an increasing proportion of treatment and care now takes place outside hospital. According to The King’s Fund, of the Health and Care Levy, roughly 18% of the budget for the next 3 years will be directed towards adult social care, to support reforms and how people in England pay for their care services. This leaves £24.9-billion (€29-billion) of funding for health services over the three years. That may be optimistic: health spending tends to rise by 3.6% above inflation. However, the spending review proposal is now estimated to raise £13-billion (€15.14-billion) a year across the period in view. This, plus updated forecasts of inflation, cost pressures and compensation for the NHS from additional employer costs of the levy, mean NHS England’s budget is now £2.5-billion (€2.88-billion) a year higher over the 2021 spending Review period (in cash terms) than was indicated in the Build Back Better announcements.

Over this Spending Review period, NHS England’s resource spending will now rise by 3.8 per cent each year on average. This includes the pre-announced £8-billion (€9.21-billion) to tackle elective backlogs over the next three years and increase activity by 30 per cent by 2024/25. “Build Back Better” was the name given to a project, overseen by the UK Treasury, to get the economy moving after a series of unanticipated disasters, including the pandemic. The measures proposed include stimulating short-term economic activity and enhancing long-term productivity through enhanced investment in infrastructure, including broadband, roads, rail networks and cities as part of the Treasury’s capital spending plans, amounting to £100-billion (€115.11-billion) in 2022.

| NOTHING TO BOAST ABOUT (OR SPEND)

Back in the early part of the 20th century, according to the Bagehot column in The Economist magazine, the five giants that had to be slain in those distant days were want, ignorance, squalor, idleness and disease. Bagehot is not impressed with our progress since then. He (or it could be ‘she’ under such a pseudonym) claims that Britain is now in the worst of all possible worlds; “a libertarian’s nightmare”, says the columnist, “with the state expanding to 45% of GDP” and the tax burden “likely to creep towards levels not seen since Clement Attlee,” the Labour prime minister who put Beveridge’s and Bevan’s plans into practice. Bagehot points to what now exists as a sort of minimalist welfare state, doing the least it can get away with.

Unemployment benefit, the column points out, is set at £80 (€92.09) a week, which is around 14% of average earnings. It’s roughly half what it used to be in equivalence terms in the 1970s. The column points out that unemployment benefit in the Netherlands begins at 50% of whatever the last payslip shows. You won’t get rich on it, but neither will you starve to death. Bagehot writes that “the NHS is the only adequately-funded part of the British state, and then barely.” The message is: don’t get ill in Britain. By the way, current waiting lists have reached the historic peak of around 7.1-million, according to the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS). The NHS target for maximum waiting time is 18 weeks, but the actual figure is beyond that and still rising. Now the nurses are planning to go on strike for the first time in the history of the NHS and it’s for more pay.

The NHS was facing pressures and strains that were hard to manage or control even before the arrival of the COVID-19 pandemic. According to the IFS: “The waiting list for elective treatment (non-urgent treatment) had grown by 50% since 2015; just 83% of A&E patients were seen within four hours in February 2020 (down from 92% in February 2015); and the estimated cost of eradicating the ‘high-risk’ maintenance backlog had quadrupled since 2010.” After ten years of annual budget increases, health spending grew in real terms by just 1.6% per year, lower than in any decade since the NHS began. The NHS couldn’t afford to grow. When the pandemic began, there were 39,000 vacancies for nurses in England. There were also fewer doctors, fewer hospital beds and fewer CT scanners per person than in many similar countries, while public pay restraint meant pay cuts for a lot of NHS staff.

“Following a decade of big budget increases, between 2009−10 and 2019−20 UK,” reports the IFS, “government health spending grew at an average real-terms rate of 1.6% per year – lower than any previous decade in NHS history.” The average pay for consultants in 2021 was 9% lower in real terms than it was in 2011. What’s more, it’s 4% lower for junior doctors and 5% lower for nurses. The IFS says that: “In our central scenario, we estimate that the English NHS will need £9-billion (€10.36-billion) in 2022−23 (an increase of 6.4% relative to pre-pandemic plans), £6-billion (€6.91-billion) in 2023−24 (4.1% on pre-existing plans) and £5-billion (€5.76-billion) in 2024−25 to deal with pandemic-related pressures. These are substantial, but manageable, sums. These estimates are highly uncertain and sensitive to assumptions about the future course of the pandemic but are broadly similar to those reached by other organisations.”

There is, clearly, no shortage of people requiring treatment for various illnesses There is a relatively severe shortage, however, of money with which to do it. The new Health and Social Care settlement announced in September 2021 provides an additional £11.2-billion (€12.89-billion) for the Department of Health and Social Care in the period 2022-23 and £9-billion for 2023-24, of which £1.8-billion (€2.07-billion) is set aside each year for social care, leaving some £9-billion (€12.89- billion) of additional funding in 2022-23 and £7-billion (€8.06-billion) in 2023-24 to cope with health-related pressures connected with COVID-19. The IFS thinks that should be enough for the following two years, but not enough in the medium term.

The IFS has calculated that the combined cost of meeting the COVID-related direct pressures could be around £5.2-billion (€5.99-billion) in 2022−23, falling to £2.0-billion (€2.3-billion) in 2023−24 and £0.9-billion (€1.04-billion) in 2024−25. However, the indirect costs and pressures associated with the pandemic could be greater and more persistent than the estimates to date suggest. “Millions of people missed out on NHS care during the pandemic,” reports the IFS. “Much of this care will need to be delivered eventually and waiting lists are likely to rise rapidly as these ‘missing’ patients come forward. We estimate that the NHS could need £2.5 billion (€2.88-billion) per year between 2022−23 and 2024−25 if it is to catch up on missed activity.” It is not a pretty picture and so far nobody is suggesting a way to get over the many, many issues.

The University of East London held an inquiry into the problems facing the NHS in the hope of coming up with possible solutions. Previous evidence to the group of MPs involved in the project mentioned poor workforce planning, weak policies and fragmented responsibilities contributing to “a workforce crisis, exacerbated by the lack of a national NHS workforce strategy”. It has been estimated that by 2030-31, up to almost half a million extra health care staff would be needed to meet the pressures of demand and to enable the NHS to recover from the COVID-19 pandemic. That is equivalent to a 40 per cent increase in the workforce. What’s more, only a quarter of nursing shifts have the planned number of registered nurses on duty, according to a new survey of more than 20,000 frontline staff. The Royal College of Nursing (RCN), representing nurses, reports that most nurses have warned that staffing levels on their last shift were not sufficient to meet the needs of patients. Some nurses are now quitting their jobs as a result.

No serious British politician would suggest scaling back the NHS; it is still the “jewel in the crown” for a caring society. Can it be saved? The question is not relevant; it WILL be saved because it HAS TO be saved, by some means. There is an old Jewish proverb: “When you have no choice, mobilise the spirit of courage.” The question is: does any current British politician have that courage? There is very little sign of it. The NHS is in a mess, but it remains an essential element of life in the UK. It can’t be abandoned but nobody can afford to fix it. It will take a huge leap of imagination to come up with a working solution, and none has been suggested – at least, not seriously – by any of the current crop of British MPs, nor by the newspapers, even though they’re not bound by promises they cannot afford to break. Britain’s NHS is going to need much more than a shot in the arm to save it, and amputation is not an option. A vast amount of that “spirit of courage” is going to be needed, whoever provides it and in whatever form.