“We must learn to live together as brothers or perish together as fools,” said civil rights leader Martin Luther King in a speech he gave in St. Louis in March 1964, two years before he was murdered by a white supremacist. It’s very sound advice but not easy to take because of the risks involved. That’s why it helps to have some sort of guarantor to make certain that if and when you lay down your weapons in a gesture of peace and good will, the other side won’t simply pick up theirs and shoot you. But given its record, who in their right mind would choose Vladimir Putin’s Russia to fulfil that rôle? It would be like the Senate of Ancient Rome inviting Hannibal and his Carthaginians to look after the Empire for them, while they pop out to the shops. Well, perhaps not. Azerbaijan and Armenia, still in dispute over Nagorno-Karabakh, should recall the words of the Prussian military commander, Helmuth von Moltke, who wrote in 1880, in a letter to a friend, “Everlasting peace is a dream, and not even a pleasant one; and war is a necessary part of God’s arrangement of the world…Without war the world would deteriorate into materialism.” Sorry, Helmuth, but I think that particular ship sailed long, long ago. We live in a world of so-called realpolitik, defined in my Chambers Dictionary as “practical politics based on the realities and necessities of life, rather than moral or ethical ideas”. Or to put it another way, “Every man for himself, and the Devil take the hindmost,” in the words of the Victorian writer and poet, Dinah Maria Craik. Certainly, in foreign policy terms, Putin and his foreign minister, Sergey Lavrov, seem to be adhering to Craik’s concept. As to underwriting a peace between Azerbaijan and Armenia, the neighbours might have chosen almost any other country in the world, one might think, with greater confidence in a peaceful outcome. But instead Armenia chose Russia. But it wouldn’t do to ignore Azerbaijan. Bakü, the world’s 20th largest oil producer, has reserves of 7,000,000,000 barrels, or in other words enough to last for another 200 years.

Given Russia’s recent history of intervening wherever it fancies (and especially where it will most annoy the West), it might seem an odd choice to many, except that both countries were once part of the Soviet Union’s mighty empire. It would seem to be that Putin and Lavrov want to restore that glory, ruling an empire the size of the Soviet Union’s but without resorting to Communism in any way. Indeed, their reign has been described as a “kleptocracy” or an “oligarchy”, a country ruled by its richest elite with the aim of their further enrichment. The Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, analysing Russia’s contributions at the United Nations, concludes that it really comes down to definitions. What the West defines as ‘international law’ is not at all how the same words are defined in Moscow. “In analyzing how Russia goes about promoting its status as a global power at the UN,” says the Endowment, “the concept of international law stands out as Russia’s most important battle line. In speech after speech, both Putin and Lavrov have stressed the importance of upholding international law. Lavrov often contrasts this law with an alternative that he maintains the West is promoting to expand Western interests and values; in a 2018 address, for example, he argued: ‘Today we can trace a tendency to substitute for international law, as we all know it, some kind of ‘rules-based order.’” Based on this unfamiliar (to us in the West) interpretation, his support for President Bashar al-Assad appears logical. However awful a government may be, however corrupt, acquisitive, murderous and cruel its leader, by Putin’s logic it deserves to retain power at any cost. No-one must be allowed to threaten that. That’s why Putin supported (and continues to support) al-Assad’s use of military force against his own civilians and even helped him to impose it.

In addition, of course, al-Assad is now somewhat in his debt, giving Russia access to strategic ports in the Mediterranean. But all of this is, supposedly, secondary: “In Russian practice,” write the Carnegie Endowment, “the legitimacy of recognized governments is absolute regardless of their origins, governance, human rights record, or any other external norm. This concept echoes Russian domestic preoccupations in the era of colour revolutions, the Arab Spring, and domestic unrest.”

HISTORICAL CONFLICT

Russia, of course, famously annexed Crimea, hitherto a part of Ukraine, and has since built a bridge across the strait that prevents large vessels from reaching a number of important Ukrainian Black Sea ports, such as Odessa and Chornomorsk. Russia has recently been accused of reinforcing its troops along the Ukraine border while flagrantly giving support to pro-Russian rebels in Donetsk and Luhansk. It seems that Lavrov’s much-vaunted belief in ‘international law’ is somewhat open to interpretation. Existing governments must be defended against rebellion unless Russia doesn’t like the government concerned and instead supports the rebels, as is the case in Donetsk and Luhansk. So where does Nagorno-Karabakh fit into this? It is described in the Encyclopaedia Britannica as “an autonomous oblast of the former Azerbaijan Soviet Socialist Republic” and as a self-declared country whose independence is not internationally recognised. The oblast covered some 4,4002 kilometres, but the Republic of Nagorno-Karabakh, as it has determinedly called itself since 1992, lays claim to a much larger 7,0002 kilometres.

It includes the north-eastern elevation of the Karabakh range of the Lesser Caucasus, its territory varying from flat and empty steppe to dense forest. The encyclopaedia defines it as a “region of Azerbaijan”, incidentally, not of Armenia, which will no-doubt annoy the Armenians, not to mention the citizens of Nagorno-Karabakh itself, most of whom are ethnically Armenian.

The entire area has been subject to wars of possession for centuries, perhaps millennia, so in some ways this disagreement over what and where Nagorno Karabakh can be said to be should come as no surprise. Not far away, Urartu had, by 900 BCE, evolved into a civilisation whose subsequent destruction is mentioned by the ancient Greek historian, Herodotus, although there’s some disagreement over who or what destroyed it. Was it the Cimmerians? Or could it have been the warlike Scythians? Or was it even, as the poet Lord Byron put it, “The Assyrian (who) came down like a wolf on the fold, / And his cohorts were gleaming in purple and gold.” Byron was writing about a different war, though, involving Babylon. If you’re interested, it’s mentioned in the Christian Bible, (II Kings, 18:13 and after), where Sennacherib’s Assyrian forces came up against “all the fenced cities of Judah, and took them”, as the Bible puts it. Sennacherib “came down” on quite a lot of cities “like a wolf on the fold”. Indeed, he was famous for it. What’s more, it’s believed that King Sennacherib (or Senecherib) was the first ruler of the Kingdom of Artsakh, which seems to have been in what is now Nagorno-Karabakh. It gets very complicated if one starts to base present-day policies on the polities of ancient history.

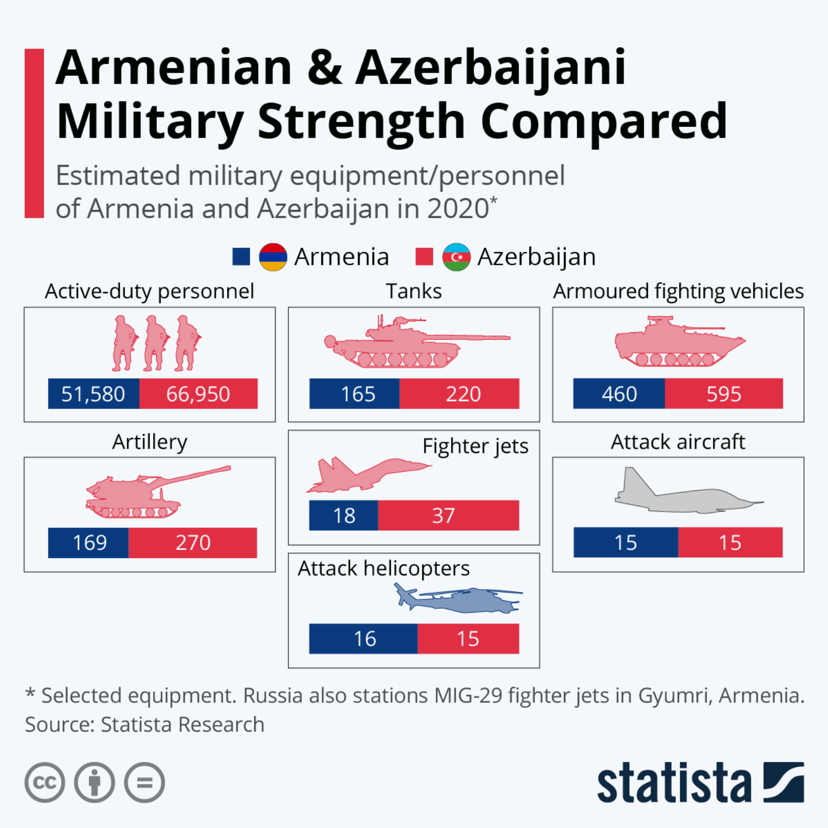

The forces of Azerbaijan and Armenia may wish to emulate Sennacherib in their method of approach, but both sides have found only inconclusive outcomes to their endeavours. During 2020, Armenia and Azerbaijan fought a six-week war over Nagorno-Karabakh. Once again, the outcome was inconclusive and the fighting didn’t stop, despite the deaths of more than a thousand soldiers and civilians. Not that such considerations seem to influence rival leaders; their citizens are dispensable; mere pawns. After all, during the Second World War, the Nazi High Command determined to seize Azerbaijan in order to gain its valuable oilfields, upon which the Soviet Union depended. Not to mention its natural gas and (more important for Russia than for the Third Reich) tea.

Despite an enormous effort, Germany’s Operation Fall Bleu (Case Blue) never quite reached the border, coming up against a Soviet force of up to 800,000 Azerbaijanis, of whom perhaps 50% were killed defending their country’s frontiers. Looking back to the more recent 2020 skirmishes, both sides, in Bakü and Yerevan, rejected attempts by the United Nations, the United States and Russia to get them to stop fighting and talk peace. Russia succeeded in getting a ceasefire in early October 2020, but it broke down, as did further ceasefires negotiated by France, Russia and the United States acting together and then by the US alone. Each side accused the other of breaching the terms of the ceasefire. To be fair, Russia appears to have done its best to stop the fighting; it negotiated the 1994 ceasefire which is still in place, although periodically ignored on the ground. Russia, for its part, is pledged to defending Armenia, while Turkey has pledged to support Azerbaijan, while neighbouring Iran is home to a large number of ethnic Azeris, which could lead to further complications and create a pretext for further confrontation.

INVITING A PEACEKEEPER

Armenia’s Prime Minister, Nikol Pashinyan, has proposed that Russian armed forces should be stationed along his country’s border with Azerbaijan (and certainly around the disputed borders of Nagorno-Karabakh) to discourage incursions by Azeri forces, although both sides would appear to be equally guilty.

Both, of course, accuse their opponents of flouting the Russian ceasefire whilst protesting their innocence. Sensible proposals are hard to spot from either Yerevan or Bakü (and certainly not from Stepanakert, the de facto capital of the disputed region, which the Azeris call Xankändi). One of the many obstacles to a lasting peace is the close proximity to one another of the soldiers of both sides, while communications between them are virtually non-existent. As a result, we see the sort of situation that arose in July this year, in which Armenia claimed that Azeri forces had opened fire on Armenian positions at the Gegharkunik section of the border, compelling Armenian forces to return fire. You will not be surprised to hear that Azerbaijan’s Ministry of Defence later claimed that it was Armenian forces that had opened fire with automatic weapons and grenade launchers towards a village in the Kelbajar region, as well as throwing hand grenades, so the Azeri forces ‘had no choice’ but to return fire. I can recall similar excuses being given, and with equal conviction, when teachers separated disputatious gangs of children in my school playground. It was a school in a fairly poor area of North East England, and disputes were rare but vicious. When they arose, they were mainly between Catholic and Protestant children, who appeared to dislike each other without quite understanding why. It’s something they had caught from their parents. Opponents invariably defended themselves with that well-worn old expression, “they started it”. My teachers never believed them, and ringleaders were usually punished. Not surprisingly, these days, diplomacy forbids the use of the cane on politicians, however blatant the lies and however troublesome the protagonists.

So, what exactly does Nagorno-Karabakh have to offer? It has vineyards and also groves of mulberry trees, where silkworms have been encouraged to breed and grow to feed the more exclusive parts of the textile and fashion industries. In addition, the region grows cereals and raises cattle, sheep, and pigs, as well as playing host to some light industry, especially in the field of food processing. It doesn’t sound like something worth dying for, although as somebody’s birthplace, it has immeasurable value, “an ill-favoured thing, sir, but mine own”, as Shakespeare put it in As You Like It. Since Moscow has succeeded in negotiating ceasefires along the Nagorno-Karabakh border, why not trust it to be an ‘honest broker’, you may wonder. The problem is that its record is hardly unblemished. After all, after Soviet forces intervened in Bakü in 1990, it led two years later to Armenian forces carrying out what has been described as one of the worst atrocities of modern times: the slaughter of 613 people in Khojaly, according to Azeri sources. They included 106 women and 63 children. Speaking to Turkey’s Anadolu Agency on the 28th anniversary of the atrocity, Khazar Ibrahim, formerly Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary of the Republic of Azerbaijan to the Republic of Turkey, said that the tragedy happened during the military aggression of Armenia against Azerbaijan, which started in the late 1980s in the dying days of the USSR. “And then it turned into the very hot period, and in 1992 Khojaly genocide was committed against Azerbaijani civilians. Elderly people, women, kids, babies were killed, maimed and taken hostage, and the fate of most of them are still not known until today,” he said. Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Armenian forces took over the town of Khojaly in Karabakh on Feb. 26, 1992, after battering it with heavy artillery and tanks, backed up by an infantry regiment.

GOING OFF BANG – OR PHUT?

Now Yerevan seems to have embraced shared security as well as political and economic integration with Russia.

It rejected the offer of an Association Agreement with the European Union in 2013 (Russia doesn’t like the EU and misses no opportunity to criticise it). Furthermore, Russia continues to supply up-to-date military equipment to Armenia, which Yerevan used during the Second Karabakh War, thus making Azerbaijan understandably nervous. There is concern, too, about the firing of Iskander missiles, which are Russian-produced mobile short-range (supposedly) ballistic missiles, targeted at Shusha, a leading Azeri cultural centre, shortly after Azeri troops had liberated it from twenty years of Armenian occupation. The Kremlin initially dismissed the claim that it was their missiles that had been used, but this was undermined by the Armenian prime minister, Nikol Pashinyan (yes, the same chap now requesting Russian troops to be stationed along the border) who said that only 10% of the missiles fired into Azerbaijan had exploded. The President of Azerbaijan had previously said he had no data to back up the claim that Iskanders had been used, so Pashinyan managed to undermine Moscow’s denials, call the Kremlin a liar and to suggest its latest short-range missiles weren’t quite up to scratch. The Armenian military were miffed, too, and there have been dark rumours about a possible coup d’état. After all, Moscow has never liked Pashinyan much anyway.

As if that were not enough, Azeri mine clearance engineers found parts of the missiles, only to discover that they were not Iskander-E missiles, which have approval for export, but were, in fact, Iskander-M types, which have a range of up to 620 kilometres. Exporting them contravenes the Missile Technology Control Regime (MTCR), under which exporting any missile with a range in excess of 300 kilometres is banned. The MTCR, created originally by the G-7 group, now includes 35 countries and is aimed at preventing the spread of weapons of mass destruction. In this case, either Russia ignored it or chose to flaunt its ability to worry the world. It certainly makes a nonsense of Moscow’s strong denials: “It wasn’t me, ‘guv, honest.” It also tends to support the perhaps somewhat unwise claims of Pashinyan that Russia’s celebrated new missile is a dud, whether or not that’s true. That won’t help Moscow to sell it around the world. Who wants to buy something that has earned a reputation as a ‘weapon of mass embarrassment’ with which to defend their interests. Russia’s involvement in the region is not, of course, to cement peace but rather to ensure that the tensions and uncertainties remain, thus ensuring Russia’s long-term rôle as the one and only power broker. Russian peace-keeping forces are garrisoned in Nagorno-Karabakh and Russia also has a military base in Armenia itself. It all helps to keep the pot simmering to Russia’s advantage, although rumours of a possible Turkish base in Azerbaijan have drawn warnings from the Kremlin. Russia may expand its interests without criticism but others (including Turkey, it seems) may not.

Armenia, then, seems to be sidling ever closer to Russia. Azerbaijan, on the other hand, has been earning itself a reputation for corruption, graft and excessive censorship. When I was in Bakü a few years ago, my guide was not keen on letting me film for more than a few seconds “in case we’re seen”. She had a palpable fear of anyone in uniform, not without good reason. I was stopped by a policeman and questioned while I was filming Bakü’s magnificent “flame towers” and their reflections in the waters of the Caspian Sea. He didn’t speak English, I don’t speak Azeri, and my interpreter had not yet arrived, so the exchange was conducted in grunts with much pointing at my passport, my camera and by showing him some of what I had shot. Later, with the interpreter in tow, I stopped to film in a market, and was constantly urged by her to get the filming finished quickly, which could involve being physically urged towards the car. The same thing happened in the street or near any of Bakü’s most popular monuments. Despite her obvious nervousness, I managed to complete my mission without further police involvement (albeit with some blurred footage).

I was conscious, however, of a certain degree of caution being exercised over exactly whom I could interview and under what circumstances. In the police control room, where I was allowed to film, a photograph of President Ilham Aliyev gazed down from the wall. Aliyev seems to be everywhere. He is always keen to stress his country’s close links with Turkey: “Many factors bind us together,” he said, when he and Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan signed the so-called Susha Declaration in June. “First of all, it is about history, culture, common ethnic roots, language, religion, national values, national interests and brotherhood of our peoples. Today, we are setting a unique example of cooperation and alliance on a global scale.” The signing will have worried Armenia and angered Russia.

KEEP IT IN THE FAMILY

Ilham Aliyev has built himself a reputation for brutality. He seems to hate much of the media, routinely refusing accreditation to foreign journalists, while imprisoning home-grown ones. Critical articles can result in a beating, with the victim being prosecuted for “disturbing public order” (and, perhaps, damaging police truncheons?). One Azeri journalist, Khadija Ismayilova, was secretly videoed with her boyfriend in an intimate moment and threatened with public humiliation unless she gave up journalism. Others, having fled the country, have subsequently been kidnapped and brought back for trial on trumped up charges.

In an interview with the BBC in November 2020, Aliyev denied many of the allegations. “We have free media, we have free Internet,” he told the interviewer. “Now, due to the martial law we have some restrictions but before there have been no restrictions.” That’s not been the experience of journalists based there. But don’t look for change any time soon: Aliyev’s success in Nagorno-Karabakh has won him support he’s never known before. “Azerbaijan’s victory in the war over Nagorno-Karabakh has transformed President Ilham Aliyev’s political stature,” reports Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, “boosting his popularity to levels he never experienced during his 17 years of authoritarian rule. The return of parts of Nagorno-Karabakh to Azerbaijan’s control, along with all seven occupied districts around the breakaway region, has changed the way many in the country view Aliyev’s leadership.” In any case, running Azerbaijan has become a family business. He married Mehriban Aliyeva in 1983 and she is now First Vice President of the country.

They have three children and five grandchildren, so there will be no shortage of descendants to assume his mantle one day. According to the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ), Aliyev and his entire family have been enjoying the country’s oil wealth. “Using a network of secretive companies in offshore tax havens,” says the ICIJ, “his family, advisers and allies set about acquiring expensive overseas homes and positions in the country’s valuable industries and natural resources, including the family’s majority control of a major gold mine that has been unknown until now.” It would explain everything for the Roman poet, Virgil, who wrote in the Aeneid: “Quid non mortalia pectora cogis, / Auri sacra fames!” (To what do you not drive human hearts, cursed craving for gold!)

Azerbaijan’s journalists are, of course, very nervous. It’s all because of the media’s rôle in uncovering what became known as the Azerbaijan Laundromat, a massive money-laundering scheme set up to enable Bakü to bribe foreign politicians to help whitewash Azerbaijan’s somewhat tarnished reputation over things like corruption and human rights abuses. During the period 2012 to 2014, several members of the country’s elite had access to a secret slush fund of some €2.5-billion with which to bribe leading European politicians, buy expensive luxury goods for themselves and ‘friends’, to launder dirty money and so on. Some of those politicians subsequently gave speeches in defence of Aliyev’s regime at the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe, although those found to have done so for money were subsequently barred from the building. The leaked banking records were revealed by the Danish newspaper Berlingske, which passed them on to the global anti-corruption body, the OCCRP. The origins of the money had been hidden through shell companies, mainly based in the United Kingdom. As the OCCRP pointed out, “Among other things, the money bought silence.

During this period, the Azerbaijani government threw more than 90 human rights activists, opposition politicians, and journalists (including the OCCRP journalist Khadija Ismayilova) into prison on politically motivated charges. The human rights crackdown was roundly condemned by international human rights groups.” Meanwhile, at least three European politicians, a journalist who wrote stories friendly to the regime, and businessmen who praised the government were among the beneficiaries of Azerbaijan’s dirty money. “Reporters for OCCRP, the Danish newspaper Berlingske, and their partners found two separate sets of documents for each of the four British companies that make up the core of the Azerbaijani Laundromat,” said the OCCRP website, which explained what the two separate sets of documents represent, “Paperwork they filed with the Companies House, where British company registration records are kept; and the filings they made when they opened accounts at Danske Bank in Tallinn, Estonia. The two sets tell different stories but have one main thing in common: The beneficial owners and directors listed in both cases are not real.” What the whole sordid affair seems to reveal, over and above the corruption at the heart of Azerbaijan’s government, is the willingness of so many seemingly respectable financial institutions in supposedly ‘enlightened’ countries to avoid looking too closely at a company’s bona fides when there’s a smell of money in the air. The French playwright Jean Anouilh wrote in “’Alouette in 1953: “Dieu est avec tout le monde…et, en fin de compte, il est toujours avec ceux qui ont beaucoup d’argent et de grosse armées” (God is on everyone’s side…and in the last analysis, he is on the side of those with plenty of money and big armies). It has always been like that since people had evolved sufficiently to stand upright and hold a spear. Or even a large rock. What it means in practice for Azeri critics of President Ilham Aliyev has been long prison sentences in appalling conditions. When Amnesty International looked at what was happening on the ground in 2017, they found that 150 people remained locked up on politically motivated charges. Even some who had fled the country have been rounded up and brought back to pay for daring to suggest Aliyev could be corrupt. The OCCRP investigation further implicated several other countries, including Armenia (surprise, surprise), Monaco, Russia, Turkey, and Ukraine, although the allegations were not immediately pursued.

PROTECTING AZERBAIJAN’S WOMEN

For the Council of Europe, committed as it to defending human rights, the way of life in Azerbaijan is embarrassing. Azerbaijan became the 43rd member state of the Council in 2001 but its record on human rights has not been exactly exemplary. Council experts are now cooperating closely with Azerbaijani authorities who are working in the field of women’s rights and the protection of women from violence, including respect for the Istanbul Convention on domestic violence. Ironically, Turkey is now seeking to abandon it, having bravely pushed it through to its widespread acceptance and adoption. The debates will lead to 16 days of activism against gender-based violence, due to be put into place in November. The scheme is to involve representatives of the State Committee on Family, Women and Children Affairs, the State Committee on the work with Religious Organisations (Azerbaijan, like Iran, is a follower of Shia Islam), the Ministry of Education, the Ministry of Health, the Ministry of Labour and Social Protection of the Population, the Commissioner for Human Rights and the various civil society organisations involved in delivering such campaigns under the Azerbaijani National Action Plan to combat domestic violence for 2020-2023. It’s a very big ‘ask’ for Azerbaijan: on the one hand, campaigning for women’s rights and freedom from violence while also trying to deal with missile attacks, Armenian and Russian territorial ambitions, and the country’s poor reputation abroad.

The plan is all very encouraging – until you look carefully at the President and his rôle in the continuing conflict. In a letter to Aliyev, the Council of Europe’s Commissioner for Human Rights, Dunja Mijatović is outspoken in her concerns, urging him not to “perpetuate and multiply the already deeply-running grievances between the communities affected by the conflict in and around Nagorno-Karabakh.” In this context, the Commissioner expresses concern at the recent inauguration of the ‘Trophy Park’ in Bakü, which reportedly displays Armenian military equipment taken as trophies during the war and shows dehumanising scenes, including wax mannequins depicting dead and dying Armenian soldiers. “I consider such images highly disturbing and humiliating,” said the Commissioner. “This kind of display can only further intensify and strengthen long-standing hostile sentiments and hate speech, and multiply and promote manifestations of intolerance.” I remember something similar in Afghanistan, where supporters of the Mujahideen (not the Taliban, you’ll note; they are very different) were selling off Russian military supplies (bits of uniform and badges, not weapons) to raise money for their cause. Whether these came from intercepted supply lines or were taken from the bodies of dead Russians I do not know, and I’m not sure I want to.

In late July, another flare-up in Nagorno-Karabakh led to the deaths of three Armenian soldiers. It was followed by an acceptance of yet another Russian ceasefire proposal “to calm tensions”. The Armenians said their forces had come under attack by Azeri forces, an incident in which four other Armenian servicemen were injured. Two Azeri soldiers were also injured by shelling, according to Azerbaijan’s defence ministry. In a statement, it accused Armenian forces of what it called “provocations” in the Kalbajar district and said its army would ‘continue to retaliate’.

It later said it had accepted a Russian proposal to enforce a ceasefire in the area, but also accused Armenia of continuing to shell Azeri positions. Armenia’s defence ministry said it, too, had accepted the ceasefire. The incident was, according to a report on Al Jazeera, “one of the deadliest since a six-week war between ethnic Armenian forces and Bakü over the Nagorno-Karabakh region and surrounding areas ended last year.” As The Halo Trust reports on its website, “However, its people have been haunted by the presence of landmines for more than two decades as a result of the 1988-94 Nagorno Karabakh War. In fact, there have been more landmine accidents per capita in Karabakh than anywhere else in the world. A quarter of the victims were children.

HISTORY REPEATS ITSELF

The whole idea of Russia playing the role of “peacekeeper” between Azerbaijan and Armenia in the Nagorno-Karabakh region is comical (or would be, were it not tragic). When in recent memory has the presence of Russian troops led to peace? Russia relies on coercive action and manipulation of the participants in any conflict into which they insert themselves. This has been no different in the late 2020 conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh. The deployment of peacekeepers to a conflict zone by any other country besides Russia would generally be seen as a step in the right direction. But when Russian troops are involved, beware. This could always be a mere Trojan Horse. Russian troops arriving for peacekeeping in the South Caucasus region is a way for Putin to reassert control over his instrument of regional manipulation – the frozen conflict between two post-Soviet states in Nagorno-Karabakh. Putin wants to be seen on both sides of the conflict as the guarantor of peace. He does this by freezing conflicts in place with no solution in sight, and not by “peacekeeping”.

For Russia, the peace agreement here was not about a cessation of hostilities, merely a means to reinsert itself into a dispute that will persist into the future, whether frozen or hot, and regardless of which ethnic group or state occupies the disputed territories. Turkey’s arrival on the scene in Azerbaijan simply gives Putin one more reason to intervene. Russia took advantage of the conflict to regain influence for itself in Azerbaijan’s internal politics. They now have their own troops installed in the region which can be used for future leverage against any move by Azerbaijan of which the Kremlin doesn’t approve. The troops could even be used as leverage in the case of open hostilities between Turkey and Russia.

Lastly, we must also remember that Putin has his secret weapon — The Wagner Group., a ‘private military company’ (PMC) We may yet see Russian PMCs like Wagner arrive in the region as a separate – and deniable – way for Russia to reassert its malign influence over the conflict. Claims of sightings of Wagner mercenaries in the region have already appeared openly in the press. As in Africa and Syria, PMC’s often take security roles and may well move into the region to give Putin a way to manipulate things behind the scenes.

Russia is also one of Azerbaijan’s main suppliers of arms. “As of today, military and technical cooperation with Russia is measured at $4-billion (€3.41-billion) and it tends to grow further,” President Ilham Aliyev said after meeting with Putin in Baku in 2013

It’s easy to get the impression that the only things to have changed since Urartu’s struggles against Cimmerians, Scythians and the seemingly wolf-like Assyrians is the size and type of the weapons used. Today we see automatic weapons, grenades and missiles being employed in the destruction of human beings, rather than Sennacherib’s “cohorts gleaming in purple and gold” with their bronze-tipped spears and swords. The end result is much the same for the victims. Nagorno-Karabakh gets its earliest historical mention in inscriptions dedicated to Sardur II, King of Urartu from 763 BCE to 734 BCE. The document was uncovered in the Armenian village of Tsovk. While I was filming in Armenia, my interpreter and guide was very keen to point out Mount Ararat, a popular place on the tourist trail, especially for Bible-minded Americans, as the place where Noah’s aek finally landed, and it’s very hard to miss. Local traditions hold that the area around Nagorno-Karabakh was the first to be settled by the descendants of Noah. The name Ararat is a Hebrew version of the name Urartu and the two volcanic mountains, Ararat and Little Ararat, are strictly speaking in Turkey, although they’re on the border. Mount Ararat is the symbol of Armenia and is clearly visible, even dominant on the horizon, when viewed from the Armenian capital, Yerevan.

Some of those who have climbed Ararat claim to have seen the remains of a ship of some sort up there, most others do not, and given the wood-and-reed shipbuilding techniques of the time, it seems extremely unlikely that much of such a vessel would remain extant. Irving Finkel, Assistant Keeper at the Department of the Middle East in the British Museum, in his book “The Ark Before Noah”, relates a Babylonian version of the story that predates the Biblical account. The Ark was, he explains, built using “quantities of palm-fibre rope, wooden ribs and bathfuls of hot bitumen to waterproof the finished vessel”. It doesn’t sound like the sort of construction likely to survive for several millennia. After all, it only had to stay afloat for six days. What’s more, in Finkel’s version, taken from a cuneiform tablet handed in to him at the British Museum, the Ark was round, like a giant coracle, but huge, extending to an impressive 3,6002 metres. I attended a lecture by Finkel, who explained his unravelling of this extraordinary document. It was fascinating. The Biblical version of the Noah story is just one of several ancient tales about a vast flood and a virtuous man who saved animals, along with his family, in what amounted to a large, round lifeboat. The version of the flood story that appears in Gilgamesh not only predates the Biblical version but also predates Homer, being at least 4,000 years old.

Ancient Urartu suffered incursions because it was in the way of migratory routes for Cimmerian nomads heading northwards and for Scythians going in the opposite direction. We know the Urartu town of Teishebaini was abandoned in around 590 BCE, after its granaries were set on fire and the whole place burned down. By 585 BCE Urartu was being controlled by the Orontid dynasty, probably ethnic Armenians, allied with the Medes, who came from Iran. As always, the local people suffered because of the ambitions of others. Will the presence of yet more soldiers, even if they’re designated “peacekeepers”, make things better? History suggests probably not, especially as they seem to include the so-called Wagner Group, a shadowy mercenary group waging unattributable wars on the Kremlin’s behalf. The group was reportedly founded by Dmitriy Utkin and it allows Putin to insert himself into bloody conflicts without apparently getting his hands dirty. They were active in the war against Ukraine in Donbass and have been reported to have been present in Donetsk and Luhansk.

The Wagner Group is now owned, it’s claimed, by Sergei Prigozhin. Incidentally, the name ‘Wagner’ had supposedly been Utkin’s call-sign, chosen because of his admiration for the Third Reich, which seems unlikely, given how bitterly Soviet Russia suffered at the hands of the Nazis before defeating them. After all, one can enjoy listening to Der fliegende Holländer without feeling obliged to raise one’s right arm in salute to a dead racist megalomaniac.

A friend of mine, the former British MEP Saj Karim, now a consultant with Haider Global, has been in Bakü, seeing for himself what’s been going on there. He served on the European Parliament’s South Caucasus Delegation for 5 years, and knows something about the long conflict. He feels the blame lies away from both Bakü and Yerevan. “I have for a long time taken the view that both Azerbaijan and Armenia are victims of Foreign policy choices made elsewhere, most notably in Moscow by President Putin. Of course no one in the region can say that but it’s a fact,” he told me. “With the changed ground realities a huge development agenda is now required. Mine clearance, resettlement of IDP’s (internally displaced persons), reconstruction, ecological challenges to name but a few. The International community has a real rôle to play. This is a time to win the peace and heal through progress for all – genuinely excluding no one in the prosperity just waiting to be seized.” I hope he gets what he has wished for. Of course, the Kremlin sells arms to both Armenia and Azerbaijan. One might well imagine that Putin doesn’t want this conflict to end, along with his malign influence in the region. Where there’s a war there’s a way, seems to be his motto. Historians may still be writing about a conflict continuing over control of Nagorno-Karabakh in another 4,000 years from now.