© Edm

“This ain’t no place for me,” sang blues singer Lightnin’ Hopkins in a country and western song, after first asking his listener to unlock the door and let him out. That must surely be the wish of everyone who ends up behind bars, having fallen foul of the law in some way. As Sonny Curtis sang: “I fought the law and the law won”. Several other performers have also sung it. It’s a good song. The fact is that Europe’s prisons “ain’t no place” for anyone by choice either. We cannot return to the barbarous practices of a century or so ago, with chain gangs and whips, but neither can we allow those with criminal tendencies free range to commit whatever crimes they want. There has to be law and order to keep the rest of us safe and relatively happy and secure. Many people don’t seem to care much what sort of treatment is handed out to felons who have been condemned by the courts, however. Some seem to think that corporal punishment is a good idea. It would certainly discourage re-offending, although some criminologists have argued that ill treatment of offenders encourages them to be more violent towards their victims, next time. Assuming there is a next time.

“We have to break with what must be broken with once and for all,” wrote Fedor Dostoesky in his novel ‘Crime and Punishment’, “and we have to take the suffering upon ourselves…freedom and power – power above all.

Power over all the tumbling vermin and over all the ant-hill!” Some bibliophiles consider Crime and Punishment to be one of the greatest books ever written. It is about a small and insignificant man who commits a crime out of desperation but who is then wracked with guilt because of it, meeting along the way some of the poorest and most pitiful citizens of St. Petersburg who are always shown according to the author’s own sympathetic viewpoint. The punishment suffered by Radion Romanovich Raskolnikov is uniquely his own: to be tortured by his own sense of guilt for killing a pawnbroker. His name is derived from the Russian word ‘raskolnik’, which means divided, as Raskolnikov clearly is. He is inclined towards confession, but his self-important intellectualism makes him suspect that he is not like other men and that his crime may be justifiable because it kept him alive. The book is still on the compulsory reading list in Russian schools. Its main theme remains as much an issue now as when Dostoevsky wrote it. Whether or not real criminals feel as divided and ambivalent about their crimes in real life I do not know. No judge is likely to view a guilty conscience as sufficient punishment for criminal wrongdoing (especially for murder, as in Rakolnikov’s case). But getting the balance right is never easy. As the American film-maker, actor and comedian Woody Allen wrote: “Human beings are divided into mind and body. The mind embraces all the nobler aspirations, like poetry and philosophy, but the body has all the fun.” It also commits most of the punishable crimes (who knows what terrible crimes are committed in the human imagination?).

According to research by both the EU and the Council of Europe, the biggest problem facing Europe’s prisons is overcrowding, although there is also the issue of underfunding. In a report prepared for the European Parliament, the researchers wrote that: “Recent empirical research shows that, in general, EU countries with the highest prison populations (Germany, France, Italy and Spain) allocate a substantial budget to the prison administration, with the exception of Poland. It is further noted that Eastern European countries spend less resources (most of them less than €50,00 per detainee per day) while Western European countries (Italy, France, Germany, and Austria) spend over €100,00, which is still below the costs incurred by northern European countries such as Ireland, the Netherlands or Sweden (between €180,00 and €380,00).” Furthermore, economic restrictions have led to reductions in the budgets allocated to prisons and prisoner welfare in some countries. Portugal is singled out in the report as having that particular problem quite badly. Overcrowding, which is a widespread problem, is cited as being of particular concern. “because of the adverse consequences for the fundamental rights of prisoners which are likely to result, in the most serious cases, in inhuman and degrading treatment.”

| HOW SMALL IS TOO SMALL?

European standards set the minimum amount of space to be granted to each prisoner, and it’s this data that is used to assess what counts as “overcrowding”. The rules establish the reference criterion for assessing what counts as overcrowding. According to the established European rules for a minimal standard of personal living space in prison, each prisoner should have 6 metres of living space in a single occupancy cell and 4 metres in a multi-occupancy cell. In either case, there must be fully-partitioned toilet facilities. There must be at least 2 metres between the walls of a cell and 2.5 metres between floor and ceiling. It sounds quite reasonable, but it cannot be assumed that failure to meet these standards counts as being incompatible with fundamental rights.

It’s a complicated set of recommendations (not exactly rules) that leave much of the interpretation to the people running the prison. In a significant number of complaints alleging insufficient living space being available to an inmate, the European Court of Human Rights considers that when a detainee has less than 3 metres of floor space in multi-occupancy accommodation, there is a strong presumption that the conditions of detention constitute ‘degrading treatment in breach of Article 3’. The EU itself lacks standards to be applied in detention facilities and therefore defines minimum standards of cell space according to case law established by the European Court of Human Rights, which is not an EU body but part of the Council of Europe.

It matters a great deal. A recent report by the United Nations says that a third of prisoners held in detention in European prisons suffer mental health problems. Suicide rates are also high. “Prisons are embedded in communities and investments made in the health of people in prison becomes a community dividend,” according to Doctor Hans Henri P. Kluge, the regional director of the World Health Organisation (WHO) at its regional office for Europe. “Incarceration should never become a sentence to poorer health,” he said. “All citizens are entitled to good-quality health care regardless of their legal status.” Taking care of the inmates is a challenge. “The second status report on prison health in the WHO European region provides an overview of the performance of prisons in the region based on survey data from 36 countries, where more than 600,000 people are incarcerated.

Research has revealed that the commonest ailment among people in prison was a mental health disorder, which affects some 32.8 per cent of the prison population. The WHO had previously raised concern about the shortage of mental health facilities in Europe’s prisons, which may go some way towards explaining why the commonest cause of death in European prisons is suicide. One in five European countries has reported serious overcrowding, which can have bad implications for the health of prisoners. The WHO has recommended that legal authorities look at alternatives to incarceration as a punishment.

Overcrowding can also help some prisoners to escape from custody. In a case in the UK, a suspected terrorist escaped from Wandsworth Prison in London by hiding under a delivery truck. He has since been recaptured but it has raised questions about his imprisonment: why was he being held in a relatively low-security facility, for instance? In the UK’s case, the Covid pandemic has led to an increase in crime, longer sentences being handed out and a backlog in cases reaching court. It has also led to an increase in the numbers of female prisoners. Although prisoner numbers have been falling in Britain for five years, the Ministry of Justice now anticipates the numbers of female prisoners reaching 4,300 by July 2025, an increase of nearly 30% from today’s figure.

| FITTING EVERYONE IN

As the Council of Europe points out, by and large, the public takes little interest in prison matters. In many Council of Europe member States, the prevailing attitude is: we need more security against crime and therefore offenders should be kept off the streets. It’s an understandable attitude among law-abiding citizens. The job of the police, courts and prison service is to protect them from criminals. Most people don’t want to be involved with criminals in their everyday lives. As a Council of Europe report put it: “we do not want to meet recidivists hardened by inhuman and degrading treatment in overcrowded prisons run by criminal gangs. We want to meet people in good physical and psychological health, people who have made their decision and have the attitude to keep it – people who have acquired the skills needed to reintegrate, re-socialise and live the normal

life of law-abiding citizens.”

The report, by Ivan Koedjikov, head of the Council’s Action Against Crime Department, said that the purpose of prison should be to help prisoners to rebuild their lives in a more positive way, rejecting crime as a means of gaining their daily bread.

Looking around Europe it would seem that there are just too many prisoners for the accommodation available. Since the start of 2023 and month by month, France has been breaking records. As France 24 reports, “prison populations hit an all-time high on July 1, according to the justice ministry, continuing to rise after reaching 120 percent capacity in April.” On 1 July, the prison population hit 74,000 for the first time. Some prisoners are now sleeping on mattresses on the floors of cells already holding two inmates. Occupancy rates have surged alarmingly in some areas, reaching a staggering 212 percent in the Perpignan prison. Things are no less worrying in Belgium. “As of February 15, there were 11,326 inmates in Belgian prisons for 9,752 available places, an overcrowding rate of 16%,” reported Le Monde. The response to this catastrophe is a plan to build four new prisons by 2030, one in Antwerp, which will be a high security facility and promised to be completed by 2025, and three in Wallonia. Together, they will provide 900 new places.

Luxembourg has an unenviable reputation: more of its prisoners escaped in 2020 than from any of the other 45 nations of the Council of Europe. In 2020, it also had the 4th highest suicide rate among prisoners. In the same year, it also had the fifth highest percentage of pre-trial detainees, 43% of them waiting to appear before a judge. 73% of them were not natives of Luxembourg, the highest proportion of foreign prisoners of the countries surveyed. Prisons in Germany have a different ethos from those elsewhere, being very much focussed on encouraging inmates to lead a life of social responsibility, free of crime, upon their release. They also have more freedom inside prison that those being held in most other countries.

Many of them have access to television and have posters on their walls. Austria has similarly good conditions for prisoners. The Leoben Justice Centre, in the south-eastern state of Styria, consistently ranks as one of the best prisons in the world, to the extent that some prisoners reportedly told Swiss tabloid Blick that “you’d stay here voluntarily – nobody will break out” when asked about the conditions.

In the Netherlands, the problem is very different. In fact, it would seem to be the reverse of what other countries are experiencing: it has too few prisoners. But it still has other issues that should be addressed urgently, according to the Council of Europe. A tour of Dutch prisons by the Council’s anti-torture committee (CPT) reported excessive security measures and verbal and racist abuse. It also reported that prisoners being held on remand often spent up to 21 hours each day locked in their cells. “While the CPT acknowledges the need for adequate security measures for those who pose an enhanced security risk,” said the report, “the highly restrictive regimes and various security measures applied in the units appeared to be excessively restrictive. There can be no justification for the routine handcuffing of persons held in these units.” The committee was also concerned about the use of force at the Rotterdam immigration detention centre, which the CPT found to be excessive. It was also worried about examples of racism there and what it considered to be the overuse of solitary confinement. The committee said that there should be “better safeguards and conditions” at the facility.

| GETTING BETTER?

Some experts have said that the UK could learn from the rest of Europe in order to improve its prison conditions. It ‘s recorded that Britain’s prisons were worse than those in several other European countries, a fact noted by the prison reformer John Howard who made a point of visiting prisons all over Europe during the late 18th century. He wrote that those in Britain were full of sick, emaciated and suffering prisoners living in “stinking hell holes”, infected with what was known at the time as “jail fever”, now known as typhus. The disease may have gone but conditions in British prisons are still awful, with prison budgets cut in the name of austerity and the numbers of frontline staff reduced by some 26%. Assaults have increased, rising by 21% in the year ending September 2022. British prisons are clearly unsafe for prisoners and staff and the number of prison officers leaving the service is on the increase. Inspections have revealed British prisons to be filthy and in no way likely to achieve the aim of rehabilitation. A recent report by the official prison inspectorate referred to one prison as “unsafe” and issued an urgent notification to the government minister responsible about high rates of self-harm and drug use within structures that were themselves very run down. In response to complaints, following an investigation by the Observer newspaper, Andrea Albutt, President of the Prison Governors Association, said “we are doing little more than warehousing people”. She also said: “With too many prisoners and too few staff, it is difficult to keep order in prison.”

So, can prisons be successful, or even admirable? Yes; we’ve already noted how Austria’s prisons are highly regarded. Norway and other Nordic countries also come high on the list of countries with good prisons. They tend to be smaller with more informal interactions between prisoners and staff, while the food is better and there are meaningful activities. The staff are better paid, too. In Iceland, inspectors saw prisoners cooking their own food, taking part in classes, and carrying out paid work, such as tending animals. It’s an object lesson in how good prisons can be if properly funded and run. They also serve the useful social function of making reoffending less likely, which is presumably the overall aim.

The organisation Penal Reform International believes that much more remains to be done concerning Europe’s penal system. “Some of the key challenges in the region include prison overcrowding, delays in the trial process, poor treatment of people in vulnerable situations and in some areas poor coordination between criminal justice agencies, lack of resources and political will to make significant reforms.” Matters were undoubtedly made worse by the COVID pandemic, which led to prisoners being locked up more and with reduced opportunities for interaction with others. Effectively, it enforced a form of solitary confinement, which is bad for discipline and which causes distress among inmates. The question now arises: how do we move forward? As the organisation writes in its annual report for 2022: “Over 11-million men, women and children are in prison around the world, a large proportion of them for minor and non-violent offences. Over 3-million people in detention are awaiting trial. Overall, crime is not rising; however, the number pf people in contact with criminal justice systems across the globe, and significantly the number of people in detention, is rising.”

There is also the additional problem of justice for women and for children. There are more than 740,000 women in prisons around the world, even though they account for 3% or fewer of the overall prison population. When women are imprisoned, of course, it also affects any children they may have. For the most part, their crimes are non-violent. The numbers of female prisoners is rising and at a faster rate than the rise in the numbers of male prisoners. In the United States, for instance, the number of women serving sentences of more than one year grew by 757% between 1977 and 2004, which is roughly twice the rate of the rise in male prisoner numbers, which comes to some 388%. Women normally constitute between 2 and 9% of the prison population, but the effect on their families – especially young children – is disproportionately greater than the imprisonment of male parents.

The United Nations wants to see greater use of alternative forms of punishment to prison, especially for female offenders. “Prisons have very serious health implications,” writes the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). “Prisoners are likely to have existing health problems on entry to prison, as they are predominantly from poorly educated and socio-economically deprived sectors of the general population, with minimal access to adequate health services. Their health conditions deteriorate in prisons which are overcrowded, where nutrition is poor, sanitation inadequate and access to fresh air and exercise often unavailable.” All in all, it is far better to keep an offender out of prison if possible, and that is especially true for women.

There is little global consistency in sentencing policies, and it means that what is seen as a major crime in one country may be viewed much more leniently in another, as Catherine Heard wrote in a blog for the Institute for Penal Reform International (PRI): “For a drug trafficking conviction you could be looking at life imprisonment and a hefty fine if you were sentenced in Thailand, but be home within months if you happened to be in the Netherlands,” she wrote. Furthermore, the number of women in prison has increased 33% over the past 20 years, compared with a 25% rise among men. Around 261,200 children worldwide are estimated to have been in detention on any given day in 2020 – up from previous estimates of 160,000–250,000 children in 2018. It’s not an encouraging sign, although offenders must receive some sort of punishment both as a discouragement to further offending and to satisfy the demands of honest citizens who demand some form of retribution, just to balance things up.

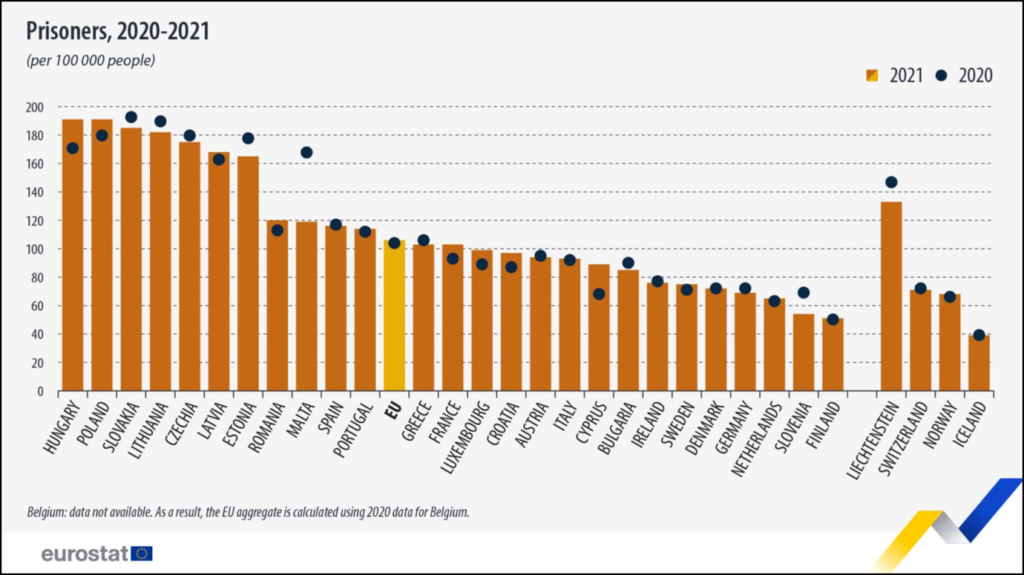

But prison is not an effective solution for the problems of law-breaking in our society. “With some research,” writes Britain’s Heywood Foundation, a public policy research body, “it is clear that, with a 65% to 77% reoffending rate and inmates facing diminished career prospects, more criminal connections, poor connection to social services, poor education opportunities – which do not link-up with other prisons or when outside of prison – and a higher chance of being introduced to substance abuse or addiction; our prisons represent extremely poor value for money.” As the World Economic Forum notes: “Most criminal justice systems around the world are increasingly reliant on prisons. Globally, the number of prisoners has grown by almost 20% since the turn of the millennium and continues to rise.” The United States has by far the highest incarceration rate with 698 out of 100,000, followed (a long way behind) by the UK with 139 out of 100,000 The lowest figure comes from Iceland with just 38. Is it worth it? The World Economic Forum says not. “In most countries, the evidence is clear that they are not. In the US, two in three (68%) of people released from prison are rearrested within three years of release. In England and Wales, two in three young people (66%) and nearly half of adults leaving prison will commit another crime within a year.” Finding an alternative form of punishment for criminals will not be an easy task, but the current system is clearly broken, so perhaps we should look hard at countries like Austria and Norway, which seem to do things better.