French President Emmanuel Macron and Federal Chancellor of Germany Angela Merkel © consilium.europa.eu

Cartoon of the month : https://europe-diplomatic.eu/society/november-cartoon-of-the-month/

It may be only 60 to 120 nanometres (nm) from side to side but you’d be amazed how much can be hidden behind a SARS-CoV-2 virus (it stands for Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Corona Virus 2, as you know). The virus in question here is, of course, the one that causes COVID-19, not to mention panic, mask-wearing, public misbehaviour, stockpiling, stupid ‘freedom’ demonstrations and, sadly, far too much illness and death. For the mathematically minded, that means this particular virus can range in size from just 6×10-8 metres up to a presumed maximum of around 120×10-7 metres, around the same size as an HIV virus. You can also express the size of the virus as being between 0.06 and 0.12 microns. In any case, extremely small, even if quite large by virus standards (the porcine circovirus measures a measly 17 nanometres, or 0.017 microns; less than a third the size). There is still some debate as to whether or not a virus is ‘alive’ in the normal sense, since an individual virus cannot ‘live’ – reproduce, in other words – without a host. Furthermore, viruses lack a cellular structure and cannot metabolize.

However, there is no dispute that they are the most numerous biological entities on Earth. It’s reckoned that we have some 1031 (that a 1 followed by 31 zeroes) virus particles in Earth’s biosphere, outnumbering all those prokaryotes that make up the bacteria and archaea, if actually weighing far less. We, of course, like our animal neighbours and co-habitants, are made up of eukaryotes, rather than prokaryotes. In many ways, a virus is a bit like some political leaders: wanting to make a bigger impact than its mere size and physical structure might suggest is possible and, certainly in this case, succeeding.

Despite its meagre proportions, though, the SARS-CoV-2 virus has been providing ample cover for some political leaders who want to clamp down on personal freedoms. We have all seen news reports of anti-masking demonstrations, mainly in America where a lot of people still blame the 5G mobile phone network for COVID-19. I’ve never been sure if they believe the radio-magnetic waves actually create a real virus or merely cause the symptoms; perhaps they’re not sure. Human scientists have been trying to recreate life in the laboratory for many, many years without success, so it’s hard to believe that people who are effectively telephone engineers have done it accidentally. The idea is simple nonsense born of scientific ignorance. It seems to be more a case of “I don’t want to face restrictions just to protect my neighbours, so I’ll just say it isn’t happening”. Ostriches have a similar panic response, I’m told. Naomi Oreskes, a professor of the history of science at Harvard University, writing in Scientific American, points out that the people denying that COVID-19 exists are often the same people who deny climate change and evolution. It is, she says, what psychologists called “implicatory denial”. She sums up the surprisingly similar arguments like this: “Climate change: I reject the suggestion that the ‘magic of the market’ has failed and that we need government intervention to remedy the market failure. Evolutionary theory: I am offended by the suggestion that life is random and meaningless and there is no God. COVID-19: I resent staying at home, losing income, or being told by the government what to do.” Basically, it means ‘believe what you like if the obvious truth is unpalatable’. Oreskes sums up, however, with an interesting conclusion. “Sooner or later, denial crashes on the rocks of reality. The only question is whether it crashes before or after we get out of the way.”

While for most of us COVID-19 has been an unmitigated disaster, for some leaders it has been an opportunity, and one which they have seized eagerly. If you’re in charge of a country and would like tighter controls over what the people get up to, what they say and what they think, then measures to combat the virus give you a golden opportunity. Who is going to question tough new restrictions when they’re imposed “for the public good”? It has meant setting aside some of the rights people have enjoyed for years or even centuries. It has meant allowing authorities enhanced rights to probe into privacy. Elections have been postponed ‘so as to prevent the need for groups to gather at polling stations’ (and incidentally to change the people in power, of course). The virus has even allowed some countries to gain a derogation from the provisions of the European Convention on Human Rights. Of course, the Convention also obliges governments to take whatever measures may be needed to protect the lives and health of the population. It does not, however, give states a free hand to, as one report puts it, “trample on rights, suppress freedoms, dismantle democracy or violate the rule of law.” Even under a ‘state of emergency’ the European Convention sets limits to protect fundamental standards.

A HOLIDAY FROM HUMAN RIGHTS?

The Convention allows for derogations in times of emergency, but “The main problem is, how far are we going to go with the limitation of certain human rights?” asks Vladimir Vardanyan, a member of the Armenian parliament. “How far are we going with the limitation of certain human rights?” We are in strange time, Vardanyan accepts, and that will inevitably mean some changes that can include limitations being imposed on the rights normally enjoyed. However, “this limitation should be proportionate, it should be lawful, it should be non-discriminatory and so on,” argues Vardanyan. There are worrying signs that the norms of civilised, democratic society are being quietly laid aside by rulers more interested in naked power than in the rights of man (and woman). The European Convention on Human Rights requires states to take whatever measures may be necessary to protect the life and health of the population. But there are limits.

What exactly have states been doing? Many of their actions are understandable, even laudable, under the present unprecedented circumstances: restrictions on the freedom of movement and assembly, the closures of educational facilities and those premises used for commercial, recreational, sporting, cultural or religious purposes. However, measures that restrict freedom of expression, access to information or freedom of the media are not. “Restricting the public flow of information,” wrote Vardanyan, “is detrimental to an effective public health response that attracts the informed and sustainable support of the public based on trust in public institutions.” Journalists, whistle-blowers and human rights defenders are key assets in preventing further damage by disclosing bad practices in good time for corrective measures to be taken. The actions of various governments have been kept under scrutiny by the European Commission for Democracy Through Law, otherwise known as the Venice Commission, which has expressed its public concern. “On numerous occasions, the Venice Commission examined the limits of such emergency powers,” it declared. “The Commission has consistently underlined that State security and public safety can only be effectively guaranteed in a democracy which fully respects the rule of law. Even in genuine cases of emergency situations, the rule of law must prevail.”

We have to remember that the Venice Commission set out its checklist of what is and is not acceptable in an emergency back in 2011, long before the SARS-CoV-02 virus turned up to rock the boat, but following bouts of less widespread epidemics. It gives little room for letting countries off the hook, however. “The security of the State and its democratic institutions, and the safety of its officials and population, are vital public and private interests that deserve protection and may lead to a temporary derogation from certain human rights and to an extraordinary division of powers. However, emergency powers have been abused by authoritarian governments to stay in power, to silence the opposition and to restrict human rights in general. Strict limits on the duration, circumstance and scope of such powers is therefore essential. State security and public safety can only be effectively secured in a democracy which fully respects the Rule of Law.”

It’s an issue that is worrying the European Parliament. Members of the Civil Liberties Committee (LIBE) concluded at a meeting at the end of October that “national emergency measures pose a ‘risk of abuse of power’ and stressed that any measure affecting democracy, the rule of law, and fundamental rights must be necessary, proportional and time-limited.

They call on governments to consider terminating their ‘state of emergency’ or at least to clearly define the delegation of powers to their executives, and to ensure that appropriate parliamentary and judicial checks and balances are in place.” The problem is that however influential the European Parliament may be, there is a distinct tendency for member state governments to ignore it. Things have moved on since Britain’s then Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher, allegedly dismissed it as “a Mickey Mouse parliament” (there is no proof that she actually said that), with MEPs gaining more powers over a wide variety of legislative areas. As a row continues at present between MEPs and the European Council, representing governments, over funding, their demands were considered irrelevant by the advisor on European affairs to the German Chancellor, who commented that “In the end, none of that is relevant”. Perhaps, but EU observers believe that in closed-door sessions, the parliamentarians may be able to squeeze from the fractious budget negotiations rather stricter rules and conditions for those countries that abuse the pandemic emergency to strengthen their own powers for purely selfish reasons.

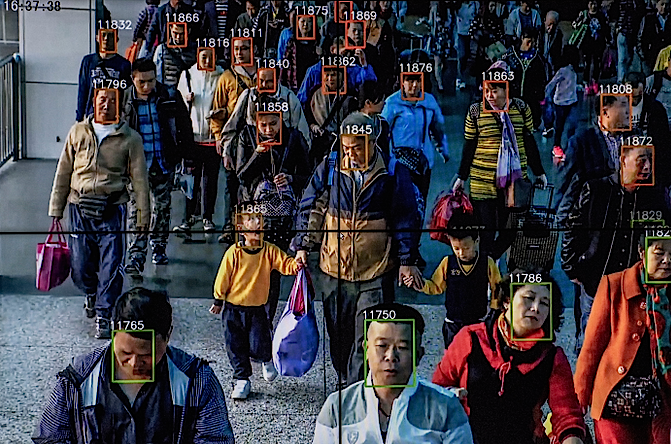

“The virus is destroying many lives and much else of what is very dear to us. We should not let it destroy our core values and free societies,” commented the Council of Europe’s Secretary General, Marija Pejčinović Burić. She warned back at the beginning of the pandemic that COVID-19 restrictions must be balanced with human rights. In some places, such as France, abuses of power have been reined in. The French police, for example, had deployed some twenty drones for surveillance of the public in Paris.

The drones were put under the control of the Prefecture of Police, whose controversial head is a renowned disciplinarian, Didier Lallement. Lallement had been specially recruited by President Macron during the Gilet jaunes protests. He made himself unpopular by claiming that COVID victims in hospital resuscitation wards were people who had disobeyed lockdown rules. This was demonstrably nonsense. The drones, though, were a step too far. France’s Human Rights League took their case to the country’s highest court, the Conseil d’État, which has imposed a ban. The French police are allowed to use drones to, for instance, follow a demonstration and identify troublemakers, which means their task is to enforce criminal law. Ensuring the enforcement of lockdown is seen as a matter of administrative rules and public health. So drones are out, at least until there is a full consultation with the Commission nationale de l’informatique et des libertés (CNIL) and a Ministerial Decree is granted, and even then only if the cameras are modified so that they cannot identify individuals.

STOP THE PRESS!

It’s not just the freedom of individuals that has come under threat – something that may be seen as vaguely understandable – but the freedom to report it. The International Press Institute reported back in April that “an alarming number of European governments, especially in eastern and central Europe, have used the ongoing health crisis as a pretext to restrict the free flow of information and clamp down on independent media. The most serious threats have so far been observed in states with authoritarian tendencies such as Hungary and Russia, where the pandemic has been exploited to grab more powers and tighten control over information.” And it’s not just the traditionally authoritarian governments, says the IPI. “Other governments with poor records on media freedom, such as Bulgaria and Romania, have also moved to introduce excessive criminal penalties for ‘fake news’ about the virus, which risk misuse and interference with the media’s ability to inform the public. Elsewhere, countries such as Serbia and Moldova have moved to control reporting, impose restrictions on journalist’s access to information, and even try to ban opinion articles.” It’s worth recalling that wartime censorship imposed early in the 1918 influenza outbreak almost certainly prevented people from taking sensible precautions and extended the duration of the pandemic.

It will come as no surprise to many that the worst offender, in terms of restricting press freedom, is Hungary, where the government passed legislation to give Prime Minister Viktor Orbàn wide new powers to rule by decree.

Orbàn’s Fidesz party voted by a two-thirds majority to give him what amount to dictatorial powers to bypass parliament for an indefinite period, despite criticism from the Council of Europe, the OSCE and a wide range of international human rights groups. Now anyone spreading what Fidesz considers ‘false’ or ‘distorted’ information – basically any view that varies from that of Orbàn – can be fined or sent to prison for up to five years. Power-grabbing is not, arguably, the best response to a deadly virus. Dealing with the infection itself would seem to be a wiser course than forming an alliance with it merely to increase a leader’s power. At the time of writing, there are some 46,000,000 confirmed cases worldwide. Despite the dismissals of its seriousness, by such leaders as Donald Trump and Jair Bolsonaro, well over 20,000,000 of those cases are in the Americas (more than 9,000,000 in the US, 5,500,000 in Brazil) and more than 11,000,000 in Europe. At one point, while Trump was playing down the significance of the disease, the United States, with 4% of the world population, hosted 20% of global COVID-19 cases. Trump’s endorsement of a remedy known not to work slowed attempts by the US health community to try to stem the spread.

Quite a few countries have discovered that a SARS-CoV-2 virus is quite big enough to conceal naked ambition, as long as news about the abuse of power doesn’t get out. That means controlling the media, and if they cannot control the message, the only answer for some is to shoot the messenger. The pressure group Reporters Without Borders has warned the United Nations Human Rights Council about widespread attempts to suppress the news, with violations of media rights in more than a third of all UN member states over the current pandemic.

They also pointed out that these violations could put everyone’s health in danger. After all, someone has to counter the falsehoods distributed by social media platforms that have been used to spread disinformation and to promote quack remedies (one suggested drinking bleach, a somewhat terminal solution). However, quite apart from the abuse and restriction of journalists and the media in general, not all of the measures introduced by heads of government can be justified as part of a defence against infection. Furthermore, reliable information is a vital weapon in combating the virus. It has been claimed that if the Chinese authorities had not censored information about the virus early on, it might have been easier to contain and its spread at least slowed.

“Some countries have taken more draconian measures than others,” said Ian Liddell-Grainger, a British member of parliament. “My own country, the United Kingdom, has put elections back. Many have changed the election process. Some have actually brought in laws and – dare I say it? – rules which do make one question whether democracy is being served?” Liddell-Grainger is very doubtful of the justifications being made for all these changes, which he insists must be temporary in any case. It’s something he made clear in his report on the crisis, adopted by Standing Committee of the Council of Europe’s Parliamentary Assembly in October, 2020, which “stresses that no public health emergency may be used as a pretext to destroy the democratic acquis and warns governments against abusing emergency powers to silence opposition or restrict human rights. Parliaments must continue to play their role of representation, legislation and oversight”. The report, among other proposals, says that “as cornerstone institutions of democracy, parliaments must continue to play their triple rôle of representation, legislation and oversight, (my emphasis) the latter being even more essential in times of emergency where the executive acquires additional powers.” “Democracy cannot be tinkered with,” Liddell-Grainger told me, “We are in a state of enormous flux and we accept that, but we have to go back to normal as soon as possible.”

He agrees that this is an almost unique set of circumstances, not seen since the deadly Spanish ‘flu epidemic of 1918-1920 that infected some 500-million people, a third of the global population at the time, and killed more than 50-million. That was an H1N1 virus, spread into the human population from birds. It was also, of course, as with the common cold, a type of coronavirus. In the United States, where around 675,000 people were killed by the virus, the Centre for Disease Control has tried to track it down and find out more about just how and why it was so deadly. Then, as now, control measures came down to hygiene, quarantine and isolation, stopping large groups from getting together and the use of disinfectants. However, now, as then, it’s necessary to hear the voices of the sufferers and those at risk. “The most important thing,” says Liddell-Grainger, referring to his report, “is that people that are in every country, every one of our forty-seven countries, need to be listened to, and they need to be listened to openly and sensibly.” At a time of national emergency, governments can assume the right to act without consultation, which he says is wrong. “Governments need to understand that they have a moral and a legal responsibility, through the Convention and through their own domestic laws, to be able to handle this in a sensible, and dare I say, responsible way.” One very practical reason for that is that for controls to be obeyed, the people have to have faith in the rules themselves and believe that their leaders are also following them. This was severely weakened in the UK when Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s advisor, Dominic Cummings, drove his family 435 kilometres to his parents’ home in County Durham while his wife was supposedly showing symptoms of the virus. It caused a furore he was not expecting and has made it much harder for Johnson to retain control. Cummings, a man who tries to avoid the media, was forced to face a hostile press conference where he performed poorly.

KNOW YOUR ENEMY

What exactly is the SARS-CoV-2 virus and how do we fight it? Scientists throughout the world would love to know all the answers. “Like all viruses, coronaviruses are expert code-crackers,” wrote William A. Haseltine, a former Harvard Medical School professor and founder of the university’s cancer and HIV/AIDS research departments. Writing in Scientific American, he clearly has some respect for this latest threat to human life. “Think of this virus as an intelligent biological machine continuously running DNA experiments to adapt to the ecological niche it inhabits,” he wrote. Imagining it as an unthinking germ that simply passes from one victim to another would sell it short. “This virus has caused a pandemic in large part because it acted on three of our most human vulnerabilities: our biological defences, our clustering patterns of social behaviour and our simmering political divides.” Haseltine was deeply involved in the fight against HIV, the human immunodeficiency virus that causes AIDS. It hasn’t gone away, but it has been tamed, thanks largely to him and his team. By the end of 2019, AIDS had killed around 33-million people. Altogether, around 76-million people have been infected and a further 1.7-million acquire the virus every year. Like SARS-CoV-2, HIV is expert at cracking DNA codes, but Haseltine and his colleagues have changed the ground plan dramatically. Of the 38-million people currently living with HIV/AIDS, 25-million are receiving full anti-retroviral treatments that keep symptoms at bay and make it far less likely that the virus will be passed on. Even so, after more than 30 years, Haseltine admits that there is still no vaccine that can prevent HIV. What are the chances of developing one for COVID-19? Not great, it seems. “These coronaviruses,” Haseltine writes, “are not a hit-and-run virus like polio, or a catch-it-and-keep-it virus like HIV. I call them ‘get-it-and-forget-it’ viruses – once cleared, your body tends to forget it ever fought this foe. Early studies with SARS-CoV-2 suggest it might behave much like its cousins, raising transient immune protection.” That is not good news. It means any immunity you may gain from having caught the virus and survived, however damaged, is likely to be short-lived. Sadly, that means that any vaccine may similarly only work for a short period, if it works at all. “Vaccines act more like fire alarms,” says Haseltine, “rather than preventing fires from breaking out, they call the immune system for help once a fire has ignited.” If your immune system fails to recognise its attacker, it may not be able to react as effectively as it might to a familiar foe.

Perhaps that explains why things seem to be getting worse. According to the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC), throughout the European Union and European Economic Area, together with the UK, the virus seems to be winning the battle. “In most countries, notification rates have increased in certain regions,” says its website, “with extremely high levels in some areas. Moreover, in addition to the substantial increases seen in most countries among younger age groups, notification rates have also increased in older age groups. Reported test positivity has been steadily increasing since August and has shown a marked escalation in recent weeks, pointing to a real increase in rates of viral transmission, rather than just a rise in reported cases attributable to increased testing.” In early October 2020, the World Health Organisation (WHO) estimated that 10% of the world population had been infected with the COVID-19 virus, with ten countries accounting for 70% of the infections. The International Labour Organisation (ILO) was also reporting concerns. “A new ILO report warned that the COVID-19 pandemic had resulted in ‘government lockdowns, collapsed consumer demand, and disrupted imports of raw materials’,” reported the WHO. In Europe, it’s been recognised that while some leaders strive for personal power, rather than an effective clinical response, there has been all-round failure. As Bloomberg reports, German Chancellor Angela Merkel has told her fellow leaders in a private video conference call that they (and she) had all failed to intervene in an effective way. She said, it’s claimed, that they had been stopped from imposing restrictions earlier by what she called ‘political realities’, but they must all learn lessons so that such a slow reaction will not be repeated.

The prognosis, it seems, is not good. Imperial College London reports that tests on more than 365,000 people in England have shown that the antibody response to the virus that causes COVID-19 wanes over time. This is consistent with Haseltine’s findings: any immunity you may gain from surviving the virus or from a vaccine of some sort is likely to be short-lived. In tests carried out over a 3-month period, “There were 17,576 positive results across all three rounds,” the College website reports, “around 30% of whom did not report any COVID-19 symptoms. After accounting for the accuracy of the test, confirmed by laboratory evaluation, and the country’s population characteristics, the study found that antibody prevalence declined from 6.0% to 4.8% and then 4.4% over the three months.” One of the report’s lead authors, Professor Helen Ward, said: “This very large study has shown that the proportion of people with detectable antibodies is falling over time. We don’t yet know whether this will leave these people at risk of reinfection with the virus that causes COVID-19, but it is essential that everyone continues to follow guidance to reduce the risk to themselves and others.”

WHO’S WINNING? NOT US

It seems sometimes as if our governments don’t know what to do. That’s because they really don’t. None of them has faced a crisis like this before and, although virology has progressed hugely since 1918-1920, it hasn’t come up with a solution, other than to advise the wearing of face coverings, the avoidance of large gatherings, trying to isolate as far as is convenient and frequent hand washing. Meanwhile, the WHO has launched a ‘COVID-19 Law Lab’ so that changes to laws resulting from the pandemic can be clearly seen. “Strong legal frameworks are critical for national COVID-19 responses,” said Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, WHO Director-General.

“Laws that impact health often fall outside the health sector. As health is global, legal frameworks should be aligned with international commitments to respond to current and emerging public health risks. A strong foundation of law for health is more important now than ever before.” The WHO also acknowledges, though, that badly designed laws that are badly implemented or enforced can be harmful, especially for marginalised populations. What’s more, they can entrench stigma and discrimination and hinder efforts to deal with the pandemic. According to Winnie Byanyima, Executive Director of UNAIDS, quoted on the WHO’s website, “Harmful laws can exacerbate stigma and discrimination, infringe on people’s rights and undermine public health responses,”. “To ensure responses to the pandemic are effective, humane and sustainable, governments must use the law as a tool to uphold the human rights and dignity of people affected by COVID-19.” It’s hoped that the COVID-19 Law Lab initiative will help people keep pace with the rapid and sometimes arbitrary way in which laws change in response to the disease. “We need to track and evaluate how laws and policies are being used during the Pandemic to understand what works,” said Dr. Matthew M. Kavanagh, Visiting Professor of Law, Assistant Professor of Global Health and Director of Global Health Policy & Politics Initiative at Georgetown University’s Department of International Health.

According to Amnesty International, plenty of governments are now hiding behind that handy virus. “Countries of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), specifically Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE),” it reports, “have used the COVID-19 pandemic as a pretext to continue pre-existing patterns of suppressing the right to freedom of expression in 2020.”

Many ordinary people, too, are only too willing to forgive their authoritarian governments and blame their fellow citizens. “Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, numerous forms of stigma and discrimination have been reported,” says UNAIDS, a joint UN programme on HIV/ AIDS, “including xenophobia directed at people thought to be responsible for bringing COVID-19 into countries, attacks on health-care workers and verbal and physical abuse towards people who have recovered from COVID-19. Attacks on populations facing pre-existing stigma and discrimination, including people living with HIV, people from gender and sexual minorities, sex workers and migrants, have also been reported.” The WHO has little time for those (some of them in positions of power and influence) who favour herd immunity as a response. As Doctor Ghebreyesus told a conference recently, “Herd immunity is a concept used for vaccination, in which a population can be protected from a certain virus if a threshold of vaccination is reached. For example, herd immunity against measles requires about 95% of a population to be vaccinated. The remaining 5% will be protected by the fact that measles will not spread among those who are vaccinated. For polio, the threshold is about 80%. In other words, herd immunity is achieved by protecting people from a virus, not by exposing them to it. Never in the history of public health has herd immunity been used as a strategy for responding to an outbreak, let alone a pandemic. It is scientifically and ethically problematic.” And, of course, it doesn’t work.

Donald Trump boasted of his immunity after recovering from the virus, but he may have spoken too soon. “In a telephone survey conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,” reported JAMA Open network, a monthly open access medical journal published by the American Medical Association, “among a random sample of 292 adults (≥18 years) who had a positive outpatient test result for SARS-CoV-2 by reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction, 35% of 274 symptomatic respondents reported not having returned to their usual state of health 2 weeks or more after testing, including 26% among those aged 18-34 years (n = 85), 32% among those aged 35-49 years (n = 96), and 47% among those aged 50 years or older (n = 89). Older than 50 years and the presence of 3 or more chronic medical conditions were associated with not returning to usual health within 14 to 21 days after receiving a positive test result.” So if you get it and get better, don’t count your chickens too early.

While ambitious leaders who are more interested in self-aggrandisement than public health draft restrictive new laws for their countries and rub their hands with glee, SARS-CoV-2 marches on, unabated. The 1918 pandemic surged in several waves over the course of two years, with many of the deaths attributed either to the virus provoking a cytokine storm, thus damaging the immune systems of young adults, or by the overcrowded and unhygienic conditions at hospital camps and in the poor housing in which many of the victims lived, and bacterial infections that took hold while patients were weakened. The war – the ‘war to end all wars’ as it was hopefully labelled – killed some 40-million people, mainly young men. The influenza pandemic killed up to 100-million of both sexes. Those tiny viruses may lack tanks, bombs and field-guns but they are even more deadly and totally indiscriminate.