I can remember reading to my daughter from Hilda Boswell’s Treasuries of Poetry. They were children’s poems, and most are credited to particular writers, but not ‘The Wraggle-Taggle Gypsies’, which is clearly meant to be a song, although I don’t know the tune. It’s all about a high-born lady in a castle who, her new husband being absent, falls for the music of a group of gypsies. So entranced is she that she takes off her costly clothes and jewels and, barefoot, goes to join the gypsies. When hubby returns, he rides off in pursuit, but meets with no success. She replies to his entreaties:

“What care I for my house and land?

What care I for money, O?

What care I for my new-wedded lord?

I’m off with the wraggle-taggle gypsies, O!”

The accompanying illustration shows the runaway bride among happy groups of rustically dressed people, smiling and dancing in what seems to be perpetual sunshine. If only that were the case.

The children’s rhymes never touch on the reality of life for Roma people. Poetry and song make them romantic figures, living on the fringe of society and off the fruit of the land. In other words, songs and poems celebrate the sort of way of life that in reality leads to violence and the tendency to drive gypsies from their property. But even when they are gone from the land, they remain in the public imagination through popular songs like “Gypsy Queen” and “It’s just the Gypsy in my soul”. Reality for most Roma people is far from idyllic or romantic. Perhaps Cher’s song, ‘Gypsies, Tramps and Thieves’ comes closest to reality, but then Cher claims to be descended from Roma people. The people themselves are often despised but it doesn’t stop the local men from turning up to watch a woman dance, and maybe, it’s darkly hinted, a little more. In that song, the family are running a travelling show, living in a wagon or caravan, and it comes as no surprise that at the 1971 World Romani Congress it was agreed to adopt a flag designed in 1933: a stylised red waggon-wheel on a background of blue over green – the sky and the grass.

Kenneth Grahame’s ‘Wind in the Willows’, a children’s book, also looks romantically at the Romani caravan: it’s the second obsession of the foolish but likeable Toad of Toad Hall (we are told his first passion was boating) who takes Ratty and Mole for a ride in one but, dislikes the work involved in camp life and so becomes obsessed with cars instead. Again, though, in this idealised view of life in Edwardian England, the Roma caravan and its associated lifestyle are seen as romantic. Incidentally, the actor Sir Christopher Lee, most famous, perhaps, for playing Dracula in the eponymous Hammer horror film, claims a Roma ancestry, too; he says ‘Lee’ is a Roma surname.

The word ‘Gypsy’ is seen as pejorative and therefore an insult; they are the Roma people, or Romani, if you (or they) prefer. Ironically, although already rejected by settled populations, the Nazis further saw them as an ‘inferior race’ and murdered them in their thousands in their extermination camps.

The Live Science website numbers the Nazis’ Roma victims at around two million. If you think such numbers could be an exaggeration, I recommend a visit to Auschwitz; it is still a ghastly place today.

We tend to imagine that Jews were the only victims of Nazi hatred (and they certainly were the main target) but there were many others: the Roma, of course, but also people with physical disabilities, gay people, even Jehovah’s Witnesses, who were compelled to wear purple triangles instead of yellow Stars of David to mark them out as ‘different’ before being condemned to the camps. For the Roma, who had been mistreated and enslaved in Europe and generally kept out of life’s mainstream for centuries, it was one more intolerable burden to bear.

TRAVELLING MUST START SOMEWHERE

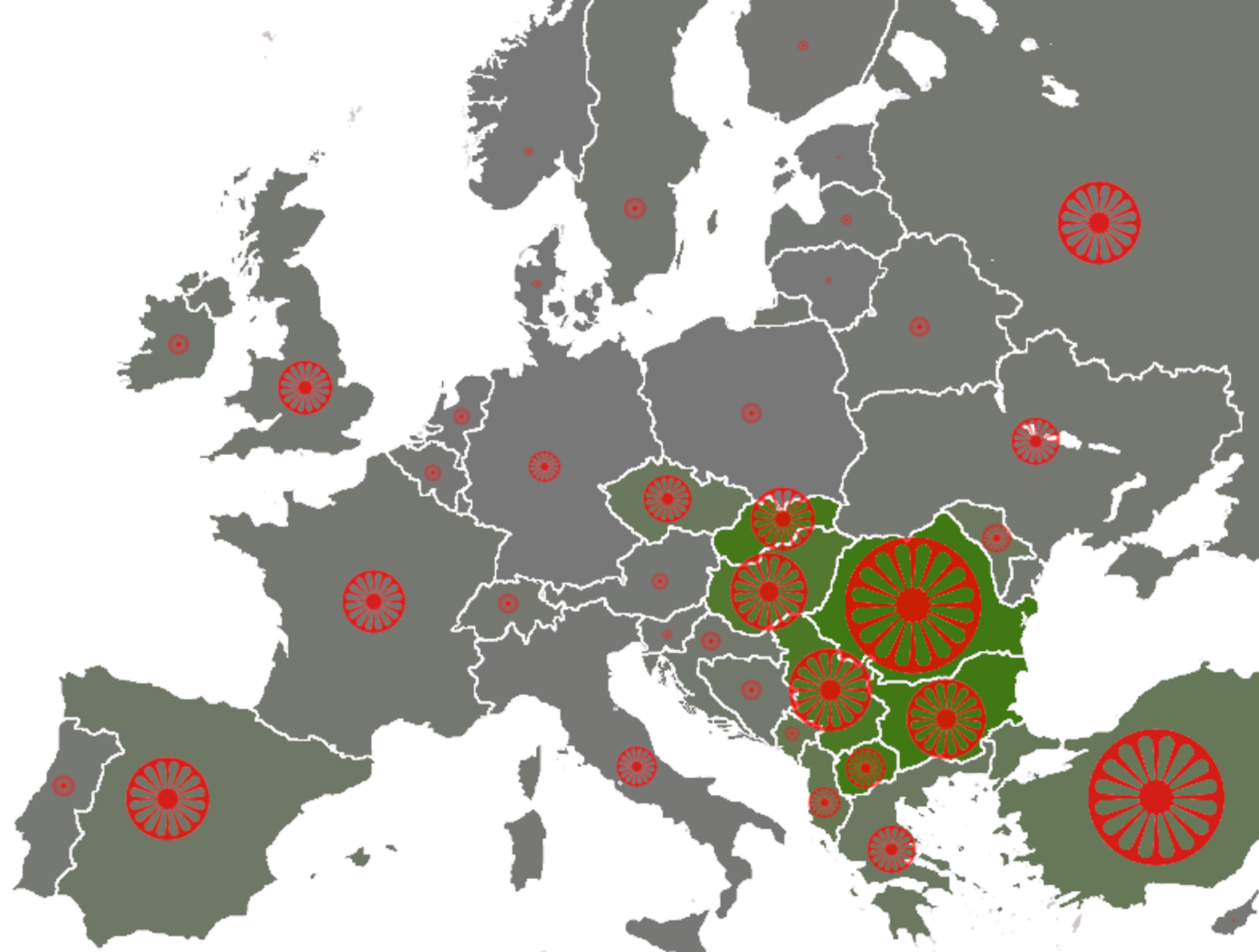

The Roma people are thought to have come originally from northern India around the 5th century, spreading across Europe from the 9th century onwards. Linguistic analysis suggests they were a Hindi people. They were seldom given much of a welcome in Europe. “There is no official or reliable count of Romani populations worldwide,” says Amnesty International. “In Europe, there are between 10 and 12 million Roma. Most of them – around two thirds – live in central and eastern European countries, where they make up between 5 and 10 per cent of the population. There are also sizeable Romani minorities in western Europe, especially in Italy (around 150,000 Roma and Travellers), Spain (600,000-800,000), France and the UK (up to 300,000 in each country).” Some estimates are far lower, anything from four to seven million in total, and one of them suggests there are only 12 million worldwide, but they are likely to be incorrect.

If the higher estimate is right, it means they number roughly the same as the population of Belgium and more than the populations of the Czech Republic or Greece or Portugal or Sweden. The populations of Hungary, Belarus, Austria, Serbia, Denmark, Finland and so on are also lower in number. They are by far and away Europe’s largest minority. In other words, in the European population league table, the Roma would come 11th or 12th out of 48. We don’t think of them like that because they have no country of their own. They’ve never been given the chance. It’s believed that there are about a million Roma in the United States, too, and almost as many in Brazil.

A Roma Project has been started at Columbia University in New York, where most American Roma live. On the project’s website, its founder, Cristiana Grigore, writes: “Even after generations-long residence, Roma are almost never considered true citizens of their countries. Regardless of their professional or economic status, Roma are often treated as the ‘unwelcome guests’ in someone else’s country. Although Roma have made significant cultural contributions to world music, dance, and literature, they remain largely under-recognized for these achievements. Moreover, Roma professionals, who practice in fields such as arts, science, medicine, mathematics, and engineering, often prefer to keep their ethnic identity hidden for fear of discrimination.” I first met Cristiana Grigore in Romania, where I was making a video report about Roma people. She was a Romanian who gained a Fulbright Scholarship to study in the US where she graduated from Vanderbilt University with an MA in International Education Policy and Management in December 2012. I had met her on a rare visit home from the States where she was studying. She had earned her BA in Psychology from the University of Bucharest in 2007 but she told me that at school she had hidden her ethnicity, fearing the reaction of her fellow students if they discovered she was Roma. Now she celebrates it and helps others to do the same. But her precocious intelligence at school earned her few friends, and angered other parents and grandparents, who complained to the teachers about her success. “How can you give the highest award to a Gypsy girl?” one mother demanded.

The history of the Roma people is not an enviable one, however romantically they are depicted in poetry and song. In Mediaeval England, Switzerland and Denmark they could be put to death, in other countries their children were often taken from them, and adults could have their ears cut off or be branded. Whatever gave Mr. Toad the idea that the travellers’ life could be fun? I have seen for myself the often-appalling conditions in which the Roma are expected to live in parts of Europe. In Romania, I visited a married couple – Eugene, his wife and two small children – who were being thrown out of their fourth-floor slum flat in the most broken-down high-rise block you can imagine. The handrails guarding its stairs were unsafe, the concrete walls were cracked and broken, the stolen electricity was arriving along bare wires dangling down the stairwell, held together with electrician’s tape. The view from the window was of more such decrepit blocks and a large area covered in foul garbage which at night became a playground for thousands of rats, moving like waves over the stinking rubbish. It was awful, but the couple couldn’t pay the rent. Yes, even such a disgusting hovel cost money.

This was not in some remote backwater, either. This was in Bucharest, the capital city of Romania, a European Union member state. In another part of the city I saw Roma people living in what would count as a slum in any language: ramshackle shacks, stretched along unmade roads with children playing in the muddy puddles.

I was told by one resident that the only future for teenage Roma girls is prostitution; a bus collected the girls from the various Roma communities around the city and took them to their ‘pitches’ on the ring road. The 17-year-old daughter of one Roma woman had been murdered, presumably by a client; her mother told me the police seemed reluctant to investigate, saying they lacked the resources to bother with the murder of a prostitute. The mother was living in a tarpaper shack, condemned to be bulldozed by police within days (they had the resources for that, at least). It was clean and immaculate, however, despite being sited under a flyover. “The EU has to do more to ensure the social inclusion of Romani people,” said Romeo Franz, the German Green Party rapporteur for a new European Parliament report aimed at improving the lives of the Roma in Europe. “For too many years, policies regarding Romani people were not binding and this has to change. We call on EU member states to officially recognise anti-gypsyism, which is the main cause of social exclusion of Romani people, and take legislative measures to combat it.”

TOO MANY PROBLEMS

The plight of the Romani people has also been drawn to the attention of the Council of Europe, and over many years it has tried to take action against the injustice and mistreatment they suffer. “The results of the monitoring activities of the Council of Europe, in particular those of the Commissioner for Human Rights and the European Committee against Racism and Intolerance (ECRI), and evidence from other sources, show that Roma and Travellers in Europe still suffer from widespread and persisting anti-Gypsyism – recognized as a specific form of racism fuelled by prejudice and stereotypes – and they are still the victims of various forms of discrimination, including school segregation and forced sedentarisation, hate speech and, sometimes, hate crimes in many Council of Europe member states.” One young mother in a Bulgarian ghetto told me how she had taken her small child to see a doctor. Lacking national insurance documents, she was asked for cash and rather more than she could afford. She explained that she could not pay and was ordered (she said very rudely) out of the surgery, still carrying her untreated sick child. I thought the oath devised by Hippocrates was supposed to prevent such things, but there again the doctor didn’t actually damage the child, thus not offending against the principal “primum non nocere”: first, do no harm. Maybe she thought it meant “first, do nothing at all.” Things are much the same in Romania.

In one camp, set up in a disused army barracks near the Romanian town of Craiova, only three outside toilets had been provided for 700 people; they had to dig new facilities. Houses looked temporary, many had leaking roofs and garbage was piled up in alleyways. The water supply, from a standpipe near the toilets, was believed to be contaminated.

Many non-Roma want the Roma people to effectively stop being Roma, to assimilate, and in Romania many of them have become one with the ethnic Romanians. But that way the Roma themselves get lost, according to Vassily Velcu, the closest thing to a leader the Roma have around the Romanian town of Craiova. Some call him the ‘King of the Gypsies’, and despite the pejorative nature of the word ‘Gypsy’ he doesn’t seem to mind. In his large house he is still amassing a vast collection of Romani memorabilia and teaching local children the Romani tongue. That can’t be easy: there are at least five distinct dialects. He believes preserving his people’s traditions and culture is important. “I was born into a family of thieves,” he told me. “I swear it’s true.

My mother was one of the best thieves. I’m not ashamed about it. You never know what might happen. From the best you get the worst and from the worst you can get the best. It’s nothing to be ashamed of. If we lose our identity, we are nothing.” The most successful way out – apart from the thieving of people like Velcu’s mother – is through education, and there are several examples of Roma children winning scholarships and studying abroad. However, in the case of the old army barracks, Roma Children were barred from the nearest school. If they wanted an education, the nearest school that would accept them was ten kilometres away: a long walk, especially during sub-zero winters through deep snow. The European Parliament resolution is determined to put an end to discriminatory practices such as that. “Providing Romani children with an equal start in life is essential to breaking the poverty cycle, say MEPs,” according to press release following the vote, “who want to end all forms of school or class segregation experienced by these pupils.

They condemn the discriminatory practice of placing them in schools for children with mental disabilities, still in place in some EU countries, and call on the Commission to continue pressing member states to desegregate, taking cases to the European Court of Justice if needed.” The latest report shows that the situation with regard to education is little changed. “Only two out of three Roma and Traveller children between the age of four and the start of compulsory schooling participate in early childhood education, the results of the survey show” it reads, rather depressingly. “School attendance for compulsory schooling reaches on average 91 %, without gender differences. However, two thirds of Roma and Travellers aged 18–24 years have completed only lower secondary education. The number of Roma and Travellers surveyed who completed tertiary education is extremely small and statistically invisible.” Grigore is not convinced the new approach will make much difference, either. “Policies for Roma regarding education, housing and health can say all the right things and have all the best intentions on paper,” she told me, “but very rarely translate into good results on the ground.”

I have to say I get a sense of déja-vu about this: I have made so many media reports and written so many articles over the last four decades or so about the mistreatment of the Roma, the expulsions, the relegating of Roma people to unsanitary ghettos among the poorest parts of towns and cities. I have welcomed the angry-sounding reports full of good intentions and well-meaning promises. And then I have returned to a Roma ghetto and witnessed open sewers where children play, dilapidated slum buildings, food shortages, a lack of proper documentation, children denied education, leaking roofs, the assumption that all Roma girls must become prostitutes and that all Roma men are crooks. Good intentions only get you so far; good deeds get you further.

SOME THINGS NEVER CHANGE

A report for the European Parliament by Professor Michael O’Flaherty, Director of the European Union’s Fundamental Rights Agency (FRA), paints a grim picture of reality for Europe’s Roma people.

In a report prepared in 2016, he wrote that: “Some 80% of Roma surveyed live below their country’s at-risk-of-poverty threshold; every third Roma lives in housing without tap water; every third Roma child lives in a household where someone went to bed hungry at least once in the previous month; and 50% of Roma between the ages of 6 and 24 do not attend school.” Bearing in mind the difficulties put in place by various local authorities (including in one case building a wall around a Roma ghetto to keep them in) the lack of schooling is not entirely their fault. A European Commission report claimed that one in four Europeans would not want a Roma neighbour. Forced to the edges of society, their sometime lack of social graces is not surprising. If a people are hated, they are inclined to hate right back. The foreword to O’Flaherty’s report also mentions that four out of ten Roma surveyed had felt discriminated against at least once in the last five years, yet only a fraction pursued the incident. “With most Roma unaware of laws prohibiting discrimination, or of organisations that could offer support, such realities are hardly surprising. But they do raise serious questions about the fulfilment of the right to non-discrimination guaranteed by the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union and the Racial Equality Directive.” O’Flaherty’s researchers, from the research company Ipsos MORI, carried out a comprehensive survey, collecting information from almost 34,000 people living in Roma households in nine European Union member states, and carrying out almost 8,000 face-to-face interviews.

The Roma are not a single group but comprise people of different ethnicity. As the report explains: “‘Roma’ and ‘Travellers’ are used as umbrella terms according to the definition of the Council of Europe. They encompass Roma, Sinti, Kale, Romanichals, Boyash/Rudari, Balkan Egyptians, Eastern groups (Dom, Lom and Abdal) and groups such as Travellers, Yenish and the populations designated under the administrative term Gens du voyage, as well as people who identify themselves as Gypsies. The agency, like the Council of Europe, adds the term ‘Travellers’ as necessary to highlight actions that specifically include them.” In the United Kingdom, there is also a group of travellers known, somewhat derisively, as Tinkers, who are generally Irish Travellers and may be unrelated to the Roma but who live a peripatetic life in much the same way. I once visited a Roma marketplace in Craiova, together with Valeriu Nicolae, who was at that time an advisor to the European Commission on Roma issues, based at the Roma and Minorities Center in Bucharest. He pointed out various small groups and identified their ethnicity by the clothes and other adornments they were wearing, although they looked very similar to my untutored eye. He also told me not to delve into where the vegetables on sale came from. He hinted that many would have been ‘liberated’ from fields the vendors had passed on their way into town. I bought a very nice cheese there which could hardly have been stolen from the roadside, but the majority of Roma have skills and try to earn their livings honestly, if they’re allowed to, even if too many only earn €2 a day. “We as Roma have a huge responsibility,” said Nicolae, “but the majority in the European Union also have a huge responsibility. At this moment we don’t have any coherent strategy towards solving Roma inclusion.”

Despite the attempts of some people who are genuinely concerned, the saga drags on: there was the European Commission’s 2011 ‘EU Framework for National Integration Strategies up to 2020’. Two years later came the Council of Europe’s ‘Recommendation on Effective Roma Integration Measures in the Member States’.

Two years later still, the United Nations produced a programme ‘Transforming Our World: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development’, which included an end to segregation for the Roma people. There will be many more, roughly every two years and accompanied by the normal publicity fanfare. And Roma children will still struggle to get educated while their parents struggle to earn enough to feed them. Discrimination against Roma people has been illegal in EU countries since the Racial Equality Directive of 2000, but the latest FRA report says it still goes on, at least in the countries surveyed: “In these six western current and former EU Member States, discrimination against Roma and Travellers is widespread, the survey results suggest. Almost half of the respondents (45 %) felt discriminated against in at least one area of life in the previous 12 months. Most frequently, respondents felt discriminated against in accessing goods and services – for example, when entering a shop (33 %) or a restaurant, night club or hotel (27 %) or when looking for a job (23 %).”

Perhaps the Roma seem so different, act so differently, because that’s the way the rest of us see them and treat them.

It’s our apparent indifference to Roma issues that is singled out in the European Parliament report. “Parliament stresses that, due to persistent anti-gypsyism, Romani people in Europe suffer the highest rates of poverty and social exclusion,” runs the press release. “MEPs therefore call for inclusive education, early childhood development and an end to discrimination and segregation.” The Parliament blames a “lack of political will”, pointing out that “a significant number of Romani people in Europe live in ‘extremely precarious’ conditions, with most deprived of their fundamental human rights.” Grigore explains it slightly differently: “Among other things, even in the case of the most assimilated and educated Roma families, the racism in society is so deep, the need to keep Roma people in low-status positions, at the margins is so high…that it’s incredibly hard to break that cycle.” Things have got worse during the pandemic because the most vulnerable Roma families are even more scapegoated and excluded. The lack of access to basic care and services makes Roma people even more vulnerable to COVID-19 and other complications.

THE SEMANTICS OF RACISM

The European Commission in its latest report “Combatting Antigypsyism” makes the point that countries that are aware of their obligations not to espouse racist and segregationist policies don’t realise that the laws cover Roma people, as well as immigrants and asylum-seekers. “The first chapter notes that antigypsyism/anti-Roma racism is sometimes misunderstood,” it says, “and not well integrated into domestic legal systems and national policies of Member States despite its recognition in the 2013 Council Recommendation. Ensuring a shared common understanding of the content of antigypsyism/anti-Roma racism appears vital.” It does seem quite likely that in countries where the Roma have lived, even if outside mainstream society for centuries, the issue is not recognised as one of race. “We also propose that Member States could opt for an alternative terminology of antigypsyism/anti-Roma racism to suit diverse contexts, but clearly stipulate that diverse groups, including Travellers, Fairground people, Egyptians, Sinti or Manouches are covered by policies tackling this specific form of racism.”

It has cropped up during discussion of the plans that terms such as “Roma” and “anti-gypsyism” are seen by other groups, such as the Sinti and Travellers, as not applying to them. The choice of words has proved important. “In the focus group discussion, most of the participants agreed with the compromise term: anti-Roma racism/antigypsyism, also giving an option for a more liberal usage at Member State level that would reflect diversity of contexts.

Germany, argued ‘I would also go for a liberal way of using different terms at the same time. Because I see Romaphobia, anti-Roma racism and antigypsyism as terms that belong to the same so-called language game. They all in different ways address the similar phenomena. I think we should be liberal when we use the term, or both or three terms and do not exclusively deal with one of these terms,’ to ensure that we cover the experience of all diverse groups in different contexts.”

Of course, the European Commission’s 2011 ‘EU Framework for National Integration Strategies up to 2020’ is drawing to a close and attention is focusing on what will replace it. There must be something and it must never again permit the expulsions of Roma people as carried out by France and Italy in 2010. I was in Strasbourg at the time and Roma groups were being rounded up and expelled, but there was one small group of them living beside a backwater of the River Ile. I had arranged a studio interview with a local politician and MEP who was all in favour of the expulsions but before that, I went with a camera crew to visit the Roma, all of whom spoke French, to canvas their views. They were interesting people and tired of being constantly moved on. A couple of hours later I gathered that they had all been expelled at the express request of the woman I was due to interview, who turned up looking surprisingly smug. I hope their removal was not down to me and my camera team. The whole affair did, however, energise the European Commission to take action. “The EU Framework for National Roma Integration Strategies (NRIS) was adopted as the European Commission’s main response to the controversial and unlawful 2010 evictions and expulsions by France and Italy of EU Roma citizens originally from Bulgaria and Romania,” says the Commission’s website.

If you want a definition of anti-gypsyism, look no further than the Council of Europe. “The European Commission against Racism and Intolerance (ECRI) of the Council of Europe defined antigypsyism in 2011 as ‘a specific form of racism, an ideology founded on racial superiority, a form of dehumanisation and institutional racism nurtured by historical discrimination, which is expressed, among others, by violence, hate speech, exploitation, stigmatisation and the most blatant kind of discrimination’”. Whatever comes next must be legally binding; the latest report makes for depressing reading. “Three major large-scale surveys conducted by the EU’s Fundamental Rights Agency (FRA) between 2008 and 2016 – EU MIDIS I, 2008; Roma survey, 2012 and EU-MIDIS II, 2016 – confirm that levels of Roma discrimination in different areas of life remain worryingly high across the EU. This study calls for the post-2020 period to tackle barriers such as antigypsyism discrimination and the lack of Roma political participation.” That is certainly a major issue. Who represents the Roma? They are not concentrated in one place, so they do not form a constituency that elects representatives. Without political representation, how can the Roma fight for their rights to be respected?

In Bulgaria, I suddenly became unpopular because officials from the local authority (or from a particular political party, I wasn’t sure which) were gathering the men of the ghetto together to see how much it would cost to buy all their votes in a block. Whoever got elected was unlikely to champion the cause of the Roma, I fear. But the EU’s latest document on scaling up Roma inclusion strategies argues that this is something that must change. “Political participation and the right to participate in the political life of a country is not only a very important component of active citizenship, but also essential for enabling Roma civil societies to tackle antigypsyism and to build capacity and ownership of transitional justice-like tools aiming at building mutual trust. Particularly for minority communities, such as the Roma, ensuring effective and equal access to participation in political and public life is an essential stepping-stone towards trust state institutions.” In fact, Roma people have voted in local elections but less so in national ones, not really seeing any party as being ‘on their side’, perhaps. “Political participation has risen in the past in both formal political fora and civil society participation,” says the report, “including protests and demonstrations. As shown in the survey run by FRA in 2011, more than 70 % of Roma respondents from Bulgaria, Greece, Slovakia and Hungary, and over 80 % in Romania stated that they voted in previous elections. However, the data for western Member States shows much lower levels of participation, with for instance only 9 % having voted in the latest French national election.”

The latest proposal acknowledges that previous plans have failed and it blames that failure on the EU. “The EU Framework for National Roma Integration Strategies was a ‘soft’ policy instrument shifting the responsibility to Roma for their lack of integration. This limited approach has not captured institutional, systemic and historically rooted antigypsyism as a specific form of racism. Despite the efforts, policy tools and funding directed to integrating Roma, this socio-economic approach therefore had very little positive impact on housing, employment, education and health.” ‘Must do better’ is what the teacher writes in the end of term report of a disappointing student. The question is, will the new approach be an improvement? I would really love to go back to the Roma ghettos I’ve seen and find clean, metalled streets, busy schools, local shops open to all and clean, properly built houses. I have a fear, however, that very little will have changed. But it is not in the Roma psyche to give up. Cristiana Grigore’s Roma Project in America has high ambitions: “The Roma Peoples Project at Columbia University envisions a world where the Roma cultures have visibility and accurate representation in academia, the media, and society at large, and that acknowledges Roma contributions to the cultural heritage of the world, while providing Roma with the opportunity to expand and flourish; a world where the human rights of Roma people are acknowledged and respected, and where Roma peoples can fulfil their full potential and speak freely about their heritage without fearing social repercussions.” It must also overcome a sense of insecurity, even inferiority, brought about by a lifetime of bad treatment. “In addition to all the external barriers Roma people face in society,” Grigore told me, “the Roma also deal with enormous internalized invisible barriers when they think they are not good enough, worthy enough, beautiful and worthy of respect and dignity enough. This is the result of centuries of bullying, belittling and treating Roma as if their role is only at the bottom. It takes enormous work to undo that in an ethically responsibly way and not use the tools of the dominant group, such as exploiting others who are more vulnerable.”

The latest European Commission proposal is a good start. It acknowledges that previous efforts have failed. Vice-President for Values and Transparency, Věra Jourová, said: “Simply put, over the last ten years we have not done enough to support the Roma population in the EU. This is inexcusable.” At the same press conference, Commissioner for Equality, Helena Dalli, said: “For the European Union to become a true Union of Equality we need to ensure that millions of Roma are treated equally, socially included and able to participate in social and political life without exception.” It’s a 10-year plan, focusing on equality, inclusion, participation, education, employment, health, and housing. I would love it to work, but based on past experience I’m not holding my breath.

J.G.