Riad Salameh © Banque du Liban

My favourite press photo of Riad Salame, Governor of the Lebanese Central Bank, comes from the L’Orient Today newspaper and shows him smiling among the country’s more-than-adequate bullion reserves in a Beirut strongroom. Surrounded by so much gold it would be very tempting to slip just one gold bar into one’s pocket, wouldn’t it? Surely, they’d never miss it? Well, they might, actually, especially with bankers from France, Germany and Luxembourg, plus one French judge, going through the books (and presumably counting those gold bars). The man at the centre of their probe is, as I mentioned, Riad Salameh, and what these scrutinizers are scrutinizing is what is most commonly labelled as ‘embezzlement’. Riad Salame and his brother both deny taking more than $300-million (€276-million) from public funds. A Lebanese judge has charged Riad Salameh with what the charge sheet rather quaintly called “illicit enrichment” last March in a separate but related investigation.

The team now investigating this alleged misappropriation of funds apparently suspect that the money was taken in order to buy real estate in France and across Europe. According to Le Monde, “Anti-corruption lawyers in Lebanon and Europe are convinced that the opening of a money laundering trial against Banque du Liban (BDL) Governor Riad Salameh in several European countries, including France, is inevitable.” But of course, that doesn’t mean that either of the two brothers is guilty. Only a court of law can decide that. At the time of writing no formal charges have been filed and the two have challenged the seizure of assets in France, according to their lawyers. Now the visiting European prosecutors are closely examining bank records that list money transfers made by Raja Salameh – Riad’s brother, you may recall – using Lebanese banks as the vehicle. The aim is to track the flow of money. Lebanese prosecutors are also looking into the same issue but have declined to share the data they have amassed; at least, up to now.

The Salameh brothers claim that they’re the victims of a coordinated campaign to blame Riad for Lebanon’s financial collapse in 2019. Salameh has been governor of Lebanon’s central bank, the Banque du Liban, for more than thirty years but the financial collapse of 2019 caused huge problems for the country’s economy, with banks paralysed and the entire country impoverished following the civil war of 1975 – 1990. Huge debts were racked up, although it’s hard to see how Salameh was responsible for all of them. His French lawyer has said that the entire case has been “politicised”, which looks very possible. The brothers argue that it’s a set-up job. “In the case file I have access to,” the lawyer told the newspaper Al Arabiya, “there is no diagram of financial flows that would directly implicate Riad Salameh through a confusion of his assets and accounts, and those of the central bank.”

72-year-old Riad Salameh has claimed in the past that his wealth was built up through his earnings at Merrill Lynch, prior to him taking on the governorship in 1993. The investigating team were also scheduled to question various witnesses and former central bank employees. The Lebanese prosecutors who earlier gained access to banking records said they were prevented from sharing the data with the visiting investigators because Riad Salameh had mounted a legal challenge against the magistrate conducting the investigation, although he has since been removed from the inquiry with a new judge being appointed to take his place, so co-operation with the visiting European team can be resumed.

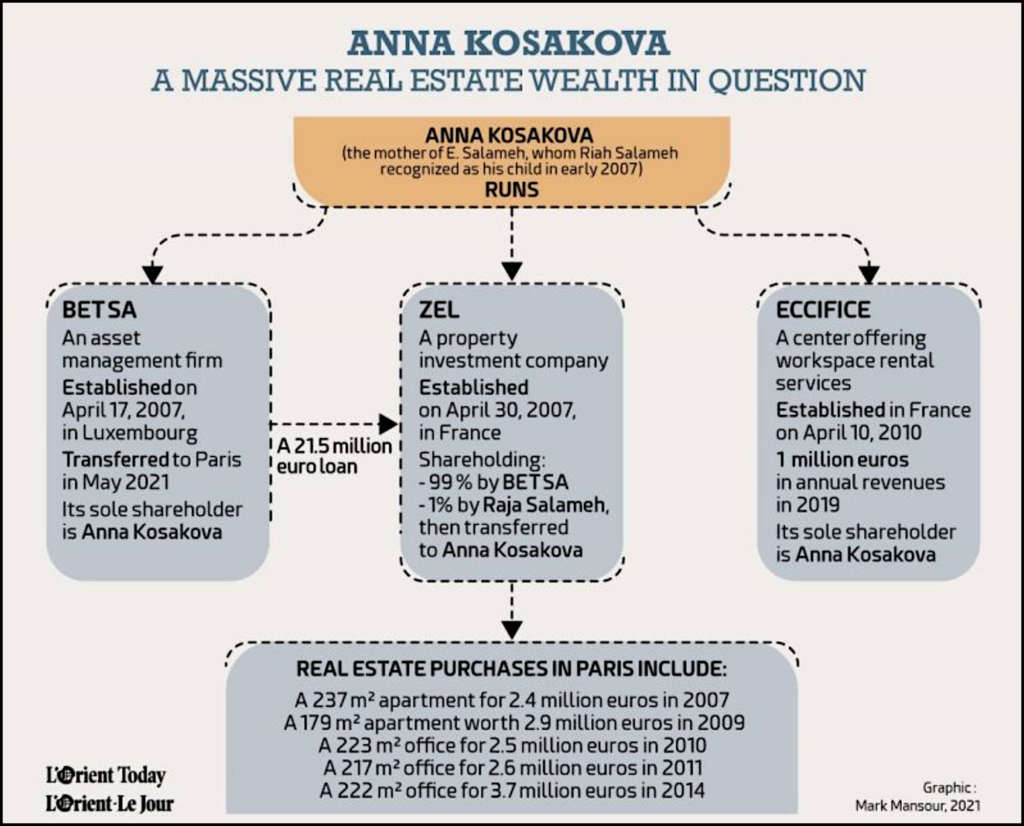

Salameh has (or had?) a Ukrainian mistress, named as Anna Kosakova, who was reported in the French journal Médiapart as having repeatedly referred investigators to Salameh during questioning. They had a child together in 2005, it was revealed, although Salameh wouldn’t recognise it as his until two years later. L’Orient Today reports that the French judge Aude Buresi indicted Kosakova in June 2022 for “criminal conspiracy”, “laundering in an organised gang” and the “laundering of aggravated tax fraud” in the case dealing with allegations of embezzlement by the Banque du Liban to the detriment of the Lebanese state.

It’s being alleged that almost €226.61-million was transferred to personal accounts belonging to Raja Salameh, the governor’s brother. He was arrested last spring, then released on bail of €3.4-million. 46-year-old Kosakova referred to Riad Salameh as “the man of (her) life”, according to the report in Médiapart. She is the first person to be prosecuted by the French national prosecutor’s office, which took over the case in July 2021 over complaints lodged last April by “the Group of Victims of Fraudulent and Criminal Practices in Lebanon” and by the French NGO Sherpa, which defends victims of economic crimes. According to the magazine Le Commerce du Levant, complaints against Kosakova included “money laundering”, “concealment”, “swindling”, “deceptive commercial practices”, “criminal association” and “lack of justification of resources” with aggravating circumstances. That’s quite a list. Unsurprisingly, it has led to Kosakova being placed under “judicial supervision” and forbidden from leaving French territory. She was also suspended temporarily from the management of the companies BET, ZEL and Eciffice, which prosecutors claim were used for money laundering. I wonder if any of their former clients have now resorted to using piggy banks instead?

| THE MORE THE MERRIER?

It’s now considered inevitable that Riad Salameh will face money laundering trials in a number of European countries, including France. But Lebanon is a financial oligarchy, which means it is effectively run by a very small number of extremely rich and powerful men. Forget democracy; in Lebanon it doesn’t appear to exist, whatever its most senior oligarchs claim.

That’s why judges from Germany, France and Luxembourg travelled to Beirut together, gathering information and talking to all those involved. The existence of the oligarchy has hindered cooperation among interested authorities, according to the Swiss foundation Accountability Now, which has filed complaints against Salameh all over Europe. According to one of the organisation’s lawyers, Zena Wakim, “Civil society and whistle blowers are getting involved like never before. The political class understands that despite their obstructions, there will always be ways to obtain information.” It has been especially difficult in this case, however, and Wakim believes the willingness of those involved to come forward and reveal details weakens Salameh’s chances of emerging from it with a clean pair of hands. “This undermines Riad Salameh’s defence that the file is empty,” she said. Certainly, the list of possible (I could say “probable”) charges he may face encourages those with inside knowledge to share it. Meanwhile, is the EU doing anything to alleviate the pain? Well, yes; quite a lot, according to L’Orient: “The European Union has allocated €229 million to “reinforce much needed reforms and economic development” in Lebanon this year, according to an EU. Total aid, according to SyriaConf2021, comes to €240-billion since 2011. There is, in addition, an assurance that the EU “continues to support Lebanon and its people during challenging socio-economic conditions” and notes that “several priorities were identified for this new financial package.” It certainly needs assurances; the statement went on to say that the first priority is to “enhance good governance and support reform,” meaning that the EU will assist Lebanon in implementing “reforms related to public administration focusing on integrity, transparency, and accountability, in line with the opportunities identified by the recent IMF Staff-Level Agreement.” Some might say: “not before time!”. They may also ask, quite reasonably, where all this aid is going.

We should bear in mind that Salameh is the longest-serving central bank governor in the world and has been credited with maintaining the stability of the Lebanese pound from his initial appointment until 2019, even if it doesn’t look very stable today! He now stands accused of corruption, money laundering and also running the biggest Ponzi scheme the world has ever seen. In a Ponzi scheme, investors are lured in and rewarded generously at first, using money from more recent investors to fund the pay-out. Although the system – which is a form of fraud, of course – is named after the Boston-based Italian businessman Charles Ponzi, who was running such a scheme in the 1920s, it’s a very old type of fraud, forming a big part of the plot in two of Charles Dickens’ novels: Martin Chuzzlewit in 1844 and Little Dorrit in 1857. Who was it who wrote: “There’s nothing new under the sun”? Oh, yes: it comes from Ecclesiastes in the Bible. It’s true, too. Anyone offered an investment that claims to be completely safe (there is no such thing as a “completely safe” investment, after all) and which offers strangely generous returns through its agents should suspect that it’s a con, with a Ponzi scheme being the most likely explanation. Just ask Martin Chuzzlewit.

| A TANGLED WEB

Riad Salameh is still denying his involvement in dishonest money-making schemes, although the evidence against him continues to build up. He is a key member of a Lebanese government team that has been in talks with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in a bid to work out a rescue deal for the country’s battered economy. A Lebanese judge has charged him with “illicit enrichment”, the first charge to be brought against the country’s central bank governor.

The judge, Ghada Aoun told Reuters that the case relates to the purchase and subsequent rental of Paris apartments, some of them to the Banque Du Liban. Salameh still denies the accusations and told Reuters that he has ordered an audit which shows categorically that his wealth didn’t come from public funds, but more and more questions seem to be arising since the 2019 collapse of the financial system. The new charge would appear to exacerbate the tensions among Salameh’s assorted backers and supporters. Judge Aoun said she had issued the charge after Salameh failed to attend a hearing.

At the time of writing, no arrest warrant for Riad had been issued, but the same judge ordered the arrest of Riad’s brother, Raja, although Raja’s lawyer dismissed the charge as “media speculation”. Riad has been banned from travelling, too, although security forces sent to bring him in failed to locate him. Like one of the country’s coins, perhaps he’s fallen down the side of a sofa? The same judge has expressed interest in a Paris office building on the Champs Elysees, apparently rented by the Lebanese Central Bank since 2010. Interestingly, the building appears to be managed by Anna Kosakova, who has now been charged with complicity in “illicit enrichment”, the same charge faced by Raja Salameh. Separately, the judge has frozen the assets of six banks while their links with the central bank are probed. It seems that negotiations for a rescue deal for Lebanon have got nowhere. It was Sir Walter Scott in his play “Marmion” who first coined the phrase: “Oh what a tangled web we weave, when first we practice to deceive.” Certainly, in the case revolving around the Salameh brothers the web would now seem to be very tangled indeed, with Salameh’s wealth being investigated by the authorities of at least five countries, although that is not proof of guilt, of course.

The ordinary citizens of the Lebanon are far from happy. The Lebanese pound has lost more than 95% of its value, leaving the majority of people in serious poverty. There are also shortages of basic goods, including medicines, despite the country having been considered “middle income” by the standards of the time. According to the Deputy Prime Minister, Saade Chami, speaking in a television interview last year, any sort of rescue seems unlikely. “Unfortunately, the state is bankrupt, as is the central bank, so we have a problem … the loss has occurred,” he said. Meanwhile, the central bank at the centre of this storm had been attempting to maintain an exchange rate of 1,500 Lebanese pounds to the dollar, until the summer of 2019, when it allowed the currency to fluctuate to whatever it seemed to be worth in terms of real buying power, having accumulated billions of dollars in losses. The World Bank has estimated that Lebanon’s economy contracted by almost 60% between 2019 and 2021. It has been described as one of the worst financial crises in modern times; the collapse of the Lebanese pound is very uncomfortable for the Lebanese people who are struggling to get by.

The effective exchange rate changes quite frequently but Lebanon’s central bank has recently set a new official rate of 15,000 Lebanese pounds to the US dollar, also allowing funds to be accessed in local currency. It was previously set at 8,000 pounds. The bank also set a limit on cash withdrawals of $1,600 for those holding accounts, the sums being withdrawn in the local currency. Depositors have been unable to access their savings since the financial collapse of 2019. Officially – and incredibly – the central bank has been maintaining an official exchange rate, but goods invariably trade at the market rate, which is very different. At the time of writing, the Lebanese pound is trading at 54,000 to the dollar.

Politics in Lebanon is a long, slow, drawn-out game involving long negotiations among the various community parties to reach some sort of consensus, which isn’t always possible. Two of the country’s MPs are currently “occupying” the parliament building in Beirut. Najat Salioba and Melhem Khalef have spent the night there with no electricity or hot water after 3 o’clock in the afternoon. Some 30 sympathetic MPs came to show their support, bringing them meals and spending the night there. The idea is to shake up the political system, according to a report in Le Monde, which seems to cover events in Lebanon with more interest and dedication than other papers. “This currency collapse has had serious impacts on all aspects of life and the economy,” Khalef told the newspaper. “The people are suffering and no one is doing anything. Lebanon has no government, no president, and no parliament. Parliament’s only duty is to elect a president, but we have a group of politicians who are waiting to share power based on clientelist and communitarianist criteria.” That’s a fairly damning indictment from an elected member of that parliament. Khalef spoke to the media from inside the parliament building by telephone. The media were not allowed to enter.

| LITTLE HOPE OF CHANGE

No attempt to remove the two MPs has been made by Nabih Berri, who has been the parliament’s Speaker for three decades, although he shows no signs of conceding anything. He has said he’s not willing to call a new session in order to elect a president until, as Le Monde puts it, “a consensus is reached behind the scenes”. Decision-making in Lebanon among the political classes seems to be based on the principle of “you-scratch-my-back-and-I’ll-scratch-yours”. It sounds rather undemocratic. What’s more, the two MPs staging the sit-in protest are members of “Thawra”, very much a minority party – with only 12 out of Lebanon’s 129 elected MPs – and further weakened by internal squabbles. The group has been unable to agree on a presidential candidate and the two staging the protest don’t want to nominate anybody at all. Meanwhile, a former prime minister, Hassan Diab, has just been charged with homicide with probable intent, along with the former interior minister and the former public works minister, over the bomb blast at Beirut port in 2020. Judge Tarek Bitar resumed his investigation after it had been paused for more than a year because of political resistance and legal complaints filed by senior officials Judge Bitar had been hoping to question.

Lebanon may not sound like the sort of place you’d choose for a holiday, but the much-admired French economist Thomas Piketty writes that it’s a very interesting place for study. “First, there is a consensus about the fact that the level of wealth and income inequalities in Lebanon is high by both international and historical standards. However, there are few studies to establish it rigorously. As in the rest of the Arab world, there is a major lack of data on poverty in Lebanon, according to the UN-Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia (ESCWA), 2005, from both national and international sources.” According to Piketty, it’s hard to draw any conclusions from official reports because they are all out of date. “The first and only countrywide study on the Lebanese income distribution is dated 1960,” he wrote. He also pointed out that Lebanon’s economic performance is atypical and hard to define: “The mediocre performance of the economy since 1990, together with political instability and the 2006 war damages further accentuated the need to undertake profound reform.” Lebanon, however, is still waiting, and seems likely to go on doing so.

Meanwhile, income tax evasion continues to plague the country’s economic planners. “This problem is particularly acute in Lebanon,” writes Piketty. “Anecdotal evidence indeed suggests that consequent amounts of income or wealth continue to elude tax returns collection.” In Lebanon’s case, the government decided to relax exchange controls in 1948, opting for a “laissez-faire” system of foreign exchange transactions. That sounds very reliable, doesn’t it?

Writing in The Public Source, researcher Karim Merhej points out that corruption among the political and economic elites is still a huge problem in Lebanon. “Since the end of the civil war, corruption within the political elites – which have used the state as a vehicle for self-enrichment and patronage-distribution – has undermined the country’s recovery and development,” he writes. After protests in 2019, various anti-corruption laws were introduced, along with the National Anti-Corruption Strategy, largely to pacify an angry populace and also to make it easier to obtain international funding, but there is a lot of scepticism over whether or not it will lead to real anti-corruption action and more accountability. To win back the trust of its people and greater trust internationally, Lebanon still has a long way to go. Merhej points out that: “As Lebanon continues to endure a multifaceted collapse, with UN data indicating that more than half of the population had fallen below the poverty line by May 2020, and with COVID-19 infection rates rising sharply in January 2021 (and remaining high for several months thereafter), confronting corruption has become a matter of survival for the Republic of Lebanon.” The big question is: can any recovery measure come in time to save the country and its poor inhabitants?

Merhaj recommends that the Lebanese government should clearly demonstrate its commitment to anti-corruption measures, with a guarantee for freedom of expression and assembly. He writes that future funding must be transparent, with support for oversight agencies, the media, and watchdog groups. He also wants to see a civil society-led anti-corruption front and laws guaranteeing the right of access to information. It was Carl Sagan, the American astronomer, physicist and cosmologist, who wrote in his book ‘The Demon-haunted World – Science as a candle in the dark’: “One of the saddest lessons of history is this: If we’ve been bamboozled long enough, we tend to reject any evidence of the bamboozle. We’re no longer interested in finding out the truth. The bamboozle has captured us. It’s simply too painful to acknowledge, even to ourselves, that we’ve been taken. Once you give a charlatan power over you, you almost never get it back.” Let’s hope that doesn’t apply to Lebanon, or at least not for long.