A convoy of funeral hearses carrying the remains of the victims of the MH17 plane crash from the airbase in Eindhoven to Hilversum, the Netherlands © Dutch Safety Board

The Schiphol Judicial Complex at Badhoevedorp, near Amsterdam was abuzz with activity once again on 1 February 2021. After a nearly three month adjournment due to the Covid-19 pandemic, the relatives of those killed in the downing of Malaysian Airlines flight MH17 feared that justice would be delayed, perhaps indefinitely. But the trial that had begun on 9 March 2020 has now resumed – albeit with no public – in this courtroom which is nearest to the point of departure of the doomed flight.

Departed, but by no means ended. The flight took off from Schiphol Airport in Amsterdam on the 17 July, 2014, carrying 283 passengers and 15 crew, bound for Kuala Lumpur.

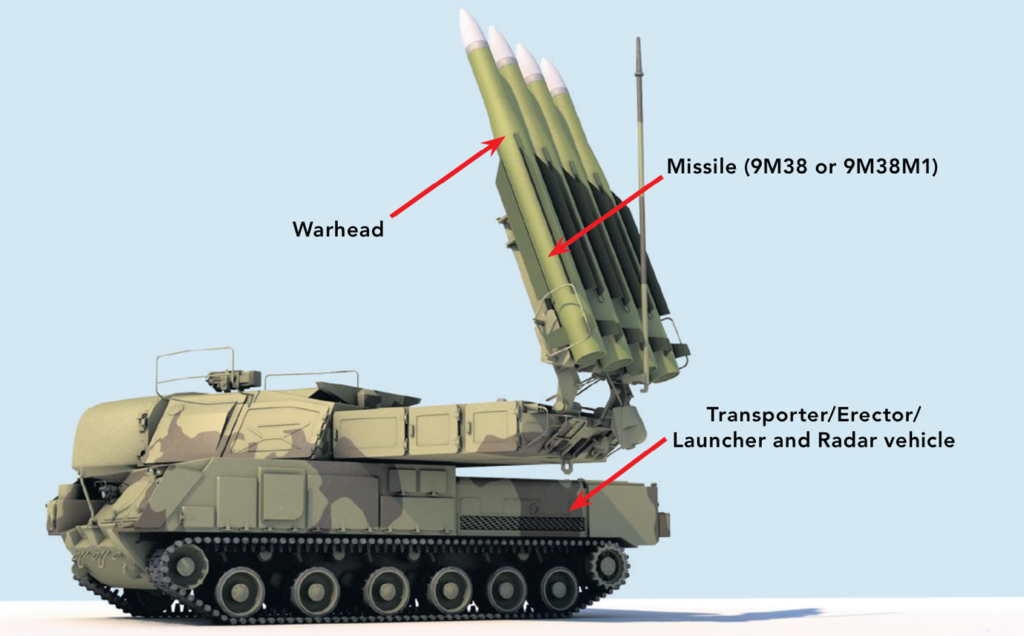

Whilst flying over Eastern Ukraine, where pro-Russian separatists were fighting Ukrainian government forces, a Russian missile destroyed it in mid-air, killing everyone on board. Contact with the aircraft, a Boeing 777-200ER, was lost some 50 kilometres from the Ukraine-Russia border and its wreckage showered down over the contested Donetsk region. It broke up into six parts, the remains of which landed across six separate sites. The Dutch Safety Board and a Dutch-led Joint Investigation Team (JIT) investigated the tangled parts scattered over the ground and concluded that it had been brought down by a Russian Soviet-era Buk surface-to-air missile, launched from rebel-controlled territory. Other members of the JIT are Australia, Belgium, Malaysia and Ukraine. The JIT’s researchers suggested that the missile, belonging to the 53rd Anti-Aircraft Missile Brigade of the Russian Federation, had only arrived from Russia on the day it was fired.

A transporter was allegedly seen by a journalist just 16 kilometres from the crash site later the same day. Other international journalists reported seeing the Buk and that it was operated by a man with a Russian accent wearing an unknown uniform. The JIT announced that Russia was primarily responsible for the attack on MH17 and for the loss of the 298 people on board at the time. The crew had all been Malaysian but just over two-thirds of the passengers had been Dutch, the rest being Malaysian, Belgian and Australian. Even on the eve of the trial opening, a spokesperson for the Russian Foreign Ministry, Maria Zakharova, dismissed the suggestion of Russian involvement as “propaganda”.

It’s arguable that the aircraft should not have chosen that route. Eastern Ukraine was a war zone where military aircraft were deployed and where some had been shot down in the preceding weeks. The International Civil Aviation Organisation had issued a warning to airlines that there was a degree of risk for commercial flights. Three days before MH17 was brought down, a Ukrainian Air Force Ilyushin Il-76 military aircraft, carrying nine crew and forty soldiers had been shot out of the sky as it approached Luhansk Airport. On that same day, a Ukrainian Air Force An-26 transport flying at 6,500 m (21,300 ft) was also shot down. American experts gave the opinion that it, too, had been brought down by a Buk, and that it had been fired from Russian territory. Russia denied it, but the day before the Malaysia Airlines tragedy, a Ukrainian Sukhoi Su-25 close air support aircraft was shot down, too, also supposedly from Russian-controlled territory.

WHO HAS THE MISSILE?

Later that same month, Russian news agencies reported that a Buk had been seized by rebels from a Ukraine military facility they had overrun. On that same day, rebels of the Donetsk People’s Republic claimed in a Tweet that they had obtained a Buk missile system; they deleted the Tweet just hours later, once it was clear that a civilian passenger jet had been downed. Indeed, just after the missile struck, the separatists boasted that they had brought down a Ukrainian military aircraft, but that claim was also promptly withdrawn when the truth emerged. Some 37 international airlines were still flying over the area when MH17 went down, despite a warning from the Ukrainian government, issued just three days before the attack, to all European countries.

The warning was reported in the Dutch newspaper, De Telegraaf. On the day of the attack, however, it was reported that a Ukrainian Antonov An-26 had been due to carry paratroopers along more or less the same route, if at a lower altitude, on their way to the battlefield. It seems possible that the rebels’ radar mistook the Boeing for the anticipated military flight. The mists of battle, though, have been deliberately fogged by those not wanting the truth to be exposed. And an attack on civilians, even in a state-to-state war is illegal. An attack by rebel groups is murder.

Which brings us to the trial, which began only on 9 March. You may not have heard much about it; news in every medium at the moment seems to have been completely taken over by the corona virus. Covid-19 is all anyone wants to talk about. On trial, but not actually present in the Dutch courtroom, are Vsevolodovich Girkin, Sergey Nikolayevich Dubinskiy, Oleg Yuldashevich Pulatov (all Russians) and Leonid Volodymyrovych Kharchenko, a Ukrainian.

They stand accused of having obtained and subsequently deployed the Buk TELAR (transport erector launcher and radar) system with the intention of shooting down an aircraft. Their guilt or otherwise is what the court has to decide. They are not accused of having deliberately targeted a passenger jet, but for rebel forces to deliberately bring down any aircraft is an offence under international law. Girkin is the former ‘defence minister’ of the self-declared ‘People’s Republic of Donetsk’. The war was not official, between two sovereign nations, and ‘combatant immunity’ cannot apply to acts of wilful murder. The Netherlands Chief Prosecutor, Fred Westerbeke, says he will summon all four to face two specific charges. Firstly they’re accused of “causing the crash of flight MH17, resulting in the death of all persons on board, punishable pursuant to Article 168 of the Dutch Criminal Code”. Secondly, the charge lists “the murder of 298 persons on board MH17, punishable pursuant to Article 289 of the Dutch Criminal Code”. So, the four are accused of deliberately bringing down the aircraft and of the culpable homicide of all those on board. None of the accused is expected to attend the court, although Pulatov is represented by his lawyer, and it’s unlikely that the court’s eventual judgement will lead to punishment for anyone found guilty.

Westerbeke warned the court in his opening statement that this is likely to be a long trial, possibly lasting five or six years, and it opened more than five years after the aircraft was shot down, so ‘justice delayed’ is inevitable, and ‘justice denied’ is highly probable; investigations into the tragedy are continuing and all four of the accused may be cleared. He also spoke of “the Russian Federation’s active efforts to obstruct the investigation” and the risks of retaliation faced by local witnesses. The JIT looked at other possible causes of the crash, such as that MH17 crashed because of an unexplained onboard explosion, that it was shot down by fighter aircraft and even that it was shot down by Ukrainian armed forces. The evidence to be presented at the trial includes documents provided by the Russian Federation. But the JIT investigators reached certain firm conclusions, according to Westerbeke “that flight MH17 was not shot down during a military exercise or by armed forces who believed that they were defending their country from a perceived attack,” he told the court in his opening statement, “The Buk-TELAR that downed flight MH17 should never have been in Ukraine, and no-one should have fired a missile there, whether aimed at a civilian or military aircraft. This makes the assessment of this case fundamentally different from cases where errors of judgment during a legitimate military operation result in the loss of civilian life. Second, the parties responsible for downing flight MH17 have taken no responsibility whatsoever for their actions.”

And, to be honest, nor are they likely to, although, as Westerbeke said, an effective investigation, openness about the findings and, where possible, the punishment of those responsible, are not merely a moral obligation. “They are also a legal obligation under international human rights conventions.” But that is not all; the Public Prosecution Service admits that many people have questioned the point of holding a trial at which the accused are unlikely to appear and when it’s questionable that the defendants, if found guilty, would face punishment. “The possibility that the defendants in this case may not face punishment, even if convicted,” the Prosecutor told the court, “is not, in our view, a reason to forego a trial.”

SNAPSHOT OF A DISASTER

In the end, it all comes back to what actually happened on that fateful day. The flight plan showed that MH17 was due to fly over Ukraine at 33,000 feet (10,060 metres), then change course and altitude to fly over the city of Dnipropetrovsk on a flight path called Airway Lima 980, flying over the city itself at 15:53 local time. Dnipropetrovsk Air Traffic Control asked MH17 to climb to a higher flightpath to avoid possible conflict with a Singapore Airlines flight, but the crew declined and the Singapore Airlines flight changed altitude instead. At 16:00 local time, the crew asked to deviate 20 nautical miles (37 kilometres) to the north because of thunder storms in the area, which was approved. At 16:19, Dnipropetrovsk ATC noticed the flight was 6.7 kilometres north of the approved flight path and instructed the crew to correct this before asking the Russian ATC at Rostov-on-Don to take over responsibility. The Russians agreed but when Dnipropetrovsk ATC tried to notify MH17 there was no response. The flight had simply vanished from the radar.

There have been many claims of intercepted calls between various suspects that suggest complicity, but the JIT fears some have been tampered with or else took place too close to the event to have any significance. As the Prosecutor said, the case must be completely watertight, without any room for question or doubt.

Meanwhile, the JIT investigation continues and is still investigating other individuals who may have played a part. Some have blamed the authorities for not doing enough, but as the Prosecutor said, “the question of whether public authorities could have done more to prevent a murder can never absolve the murderer”. It was only following an extensive investigation over an extended time period that the JIT was able to conclude that “ flight MH17 was shot down by a Buk-missile launched from a farm field near the town of Pervomaiskyi, to the south of the town of Snizhne; that a Buk-TELAR of the 53rd Anti-Aircraft Missile Brigade of the Russian army had been used for this purpose; and that this Buk-TELAR system was transported from the Russian Federation on the night of 16-17 July 2014 and the remaining three missiles on the launcher were transported back to the Russian Federation shortly after the downing of flight MH17.”

Russia has not been at all helpful to the investigation; there have even been allegations that Russia manipulated images to obscure the truth. In July 2015, Malaysia proposed that the United Nations Security Council set up an international tribunal to prosecute those found responsible for shooting down the aircraft. The Malaysian resolution gained a majority on the Security Council, but it was vetoed by Russia, which then proposed its own rival draft resolution, pushing for a greater U.N. role in an investigation into what caused the crash and demanded justice, but the proposal stopped short of setting up a tribunal: no trial, no verdict, no punishment. Russia’s lack of cooperation prompted Tony Abbott, the Prime Minister of Australia at the time of the incident, to say that “With MH17, Russia has demonstrated that there’s a touch of evil at the heart of their government.”

INEXPLICABLE EVENTS

Since then, the Dutch Public Prosecutor’s office have sought the extradition of a Ukrainian, Volosdymyr Tsemakh from the Russian Federation, although it has not been decided if he will face prosecution. The evidence against him is not so strong as the evidence against the four accused. Even so, many feel it was odd that Ukraine, willingly or unwillingly, surrendered Tsemakh to Russia in a prisoner exchange in September last year at Russia’s insistence, especially as he was a key witness in the investigation and part of the legal proceedings. Australia expressed its deep concern about the prisoner exchange.

The Australian government wanted Tsemakh to be questioned by the JIT and for Australian federal police to be involved, while recognising the pressure Kyiv was in from Moscow to do the deal. Australia’s Foreign Minister, Marise Payne said “Australia is disappointed, however, that Mr. Vladimir Tsemakh, a person of interest in connection with the downing of MH17, was included in the exchange.” Payne believes that it will be harder to bring justice to Tsemakh if he lives in Russia.

Another colleague of the accused has also been mentioned, Igor Bezler, who, in an intercepted telephone conversation on the afternoon of 17 July, 2014, told the person to whom he was talking (not identified) that a ‘bird’ was coming his way.

This was just before MH17 was brought down, but investigators were unable to establish a definite connection. Two other suspects are only known by their codenames, ‘Orion’ and ‘Delfin’, both thought to be high-ranking Russian officers who were involved in the conflict in Eastern Ukraine. In an intercepted telephone conversation on 14 July, 2014, Orion was heard to say that ‘they’ now have a Buk and are going to shoot down aircraft. Investigations have shown, though, that in the days prior to 17 July, various people and groups were trying to obtain a Buk and Orion’s conversation may have referred to a Buk-TELAR brought across the border from Russian but which then caught fire accidentally before it could be used.

As to the actual impact, the Dutch Safety Board has made very clear the sequence of events as they believe it to have taken place. Forensic research has shown that a 9M38-series Buk missile was fired, carrying a 9n314M warhead, which was surrounded by 800 iron fragments, intended to spread very rapidly, even lethally, on detonation. The missile had a proximity fuse, designed to detonate when the distance to the target is less than a pre-set amount. It detonated just above and to the left of the cockpit, the fragments tearing through the cockpit and business class sections of the aircraft. Some of the fragments – mainly small metal cubes or what were described as ‘bow tie shaped’ pieces of metal – were found in the bodies of the cockpit crew. I have seen similarly-shaped fragments – shrapnel – that had been part of Russian anti-personnel mines dropped in Afghanistan during Russia’s war with the Mujahideen.

They are designed to do the maximum possible damage to human tissue. Coupled with the explosion, this shower of fragments sucked air out of the body of the plane, causing it to break up into six sections which all came down to earth separately. The JIT’s description of what happened is based on the accounts of eyewitnesses who claim to have seen the missile being fired, on remnants of the aircraft and of the Buk missile found at the crash sites, on satellite images and data from radar and even on photos and videos of the missile being transported to Donbas, which is held by pro-Russian separatists and from where it was fired.

The trial in Amsterdam is not the only legal case to be brought. Groups of relatives of the victims have brought two cases to the European Court of Human Rights. One of them, prepared by American lawyer Jerry Skinner, demands compensation of €6.4-million from Russia for each of the victims.

Advocate Skinner made a name for himself in the trial held in May 2000 over the downing of Pan Am flight 103 over the Scottish town of Lockerbie in December 1988. Skinner is acting on behalf of forty families of victims and he told the court: “Such a weapon as the Buk missile system, from which MH17 flight was downed, could not leave the territory of Russia without the permission of officials. Probably, we will hear the names of the advisors close to Putin who maintained close links with actors in the east of Ukraine. I believe we will hear about Putin.”

I’m sure we will, but the denials will continue: Russia’s new Tsar sees his own position as bomb-proof. It’s only his political rivals that have much to fear. The European Court called upon Russia to respond to the charges put but has not published what the Russians said. Additionally, four relatives have filed a separate suit at the ECHR, this time against Ukraine for not closing off the airspace over the conflict zone. They had closed it below 8,000 metres only. Strangely, Russia imposed its own ban up to an altitude of 16 kilometres shortly before MH17 was brought down, 16 km being the maximum altitude for a Buk missile.

WHO’S WHO

The problem with cover-ups is that they have to be cohesive, consistent and persuasive, and the JIT do not believe this to have been the case with the MH17 disaster. They have published material that was recorded with the participation of militants and a senior Russian official, made in July 2014. The official in question allegedly stated that “men are coming from Shoygu (Russian Defence Minister Sergey Shoygu) and that they “will kick the local warlords out of the units”.

The same official is claimed to have said to the person being quoted, “you will report to our Minister of Defence. Our Minister of Defence is Strelkov (the codename of Vsevolodovich Girkin), and our Commander-in-Chief, like any other President or Prime Minister, is Borodai.” (Aleksandr Borodai, a Russian) According to the investigators, a few former militants told them that the Russian Security Service (FSB) and the Military Intelligence Service (GRU) were deeply involved in running the so-called Donetsk People’s Republic (DPR), one of them reporting that the leaders of the DPR regularly travelled to Moscow to consult both the FSB and GRU.

JIT investigators remain convinced that at least some of the leaders of the DPR had been sent there by Moscow. Some witnesses had said that they came from inside the Russian Federation. Just after MH17 was brought down, Girkin announced to Borodai that he was leaving to “return to HQ”. In August that year, both Girkin and Borodai travelled to Moscow. In an interview in 2017, it’s claimed Girkin said “I was ordered to pass the command to Zakharchenko”. Germany has repeated a call for Russia to start getting involved in the investigation. “Those responsible for this crime, the destruction of MH17 flight aircraft,” said German Foreign Office spokesperson Maria Adebar, “must be identified and brought to justice, and, of course, Russia should co-operate constructively in the investigation of this crime.” That might seem like wishful thinking, with Russia appearing not to take the whole thing seriously, variously accusing Ukrainian ground troops, a Ukrainian fighter jet and even, on one bizarre occasion, suggesting that what had been brought down was an aeroplane full of dead bodies supplied by the United States and put aboard an otherwise empty flight just to blacken Russia’s name. Few outside Russia believe that, especially the relatives of the murdered passengers and crew.

So who allegedly is to blame? Prosecutor Westerbeke made that clear in his opening statement where he believes all the evidence points. “Among the DPR fighters,” he told the court, “we view Girkin, Dubinskiy, Pulatov and Kharchenko as leading players in the downing of flight MH17. Girkin and Dubinskiy were top military leaders of the DPR. Pilatov and Kharchenko were Dubinskiy’s direct subordinates. Together, these four men took delivery of the Buk-TELAR from the Russian Federation and deployed it as part of their own military operation, with the aim of shooting down an aircraft.” Others, Westerbeke said, may have played lesser rôles, instrumental in shooting down the aircraft, but the responsibility rests with the four accused. “The crew of the TELAR pressed the button,” said the Prosecutor, “but according to the indictment it was Girkin, Dubinskiy, Pulatov and Kharchenko who directed the employment of this weapon in order to serve their own interests. They were in command of others; they directed the Buk TELAR to the launch location; they talked during intercepted communications about the need for a Buk to serve their cause and whether ‘their’ Buk had done its job; they noted with delight that an aircraft had been shot down; they directed others in the delivery of the system to the launch site and they organise the removal of the Buk-TELAR to the Russian Federation. When it comes to evidence and responsibility, as of now no other suspects in the investigation are in the same position as Girkin, Dubinskiy, Pulatov and Kharchenko.” It is the wish of the JIT that the minor players who have been named – the alleged button-pressers, the guards who watched over the TELAR and others – should face justice in Ukraine itself.

Later in the speech, Westerbeke concedes that the murders of innocent foreign civilians may not have been the aim, although it was the effect. “It is perfectly conceivable that the true intention of these defendants was to shoot down an aircraft of the Ukrainian armed forces.” Bear in mind, they may be cleared of all charges, of course. In fact, he went on to say that some of the evidence uncovered by the JIT points towards what he called “this error scenario”. But that makes no difference under Dutch law. To clarify, he told the court that there is a guiding principle: “wars are fought between combatants, and that civilians are not involved in any way. When despite this principle civilians in Ukraine use violence against Dutch, Malaysian, Australian and Belgian citizens, this violence falls under the scope of the ordinary criminal laws of these countries.”

He said it didn’t make any difference if the perpetrators used a rifle or an advanced rocket system and also regardless of whether the intended victims were civilians or combatants. “Our preliminary conclusion,” he said, “is therefore that the suspects were not entitled to claim combatant immunity in July 2014, and that they had no right or excuse to use violence in Eastern-Ukraine,”

THE STRONG LANCE OF JUSTICE

Judge Yolande Waynobel, responsible for liaising with the media in this case, spoke of the vast volume of evidence amassed by the JIT. “The prosecutor’s office has handed over a lot of materials to us,” she said, “Now the matter is much larger than it was in November. The question is whether these materials are complete. On Monday, the judge will answer this question. If he considers that the file is finished, he can decide to look into the case. But this does not mean that new materials cannot be added to the file.” It will be difficult to add much more material; many dozens of witnesses have spoken about what they claim they saw, what they think they knew and what they may or may not have heard, but in the Russian-controlled DPR and in the Russian Federation itself, they run a serious risk if their statements are seen as ‘traitorous’. For that reason, the identities of many of those witnesses are to remain secret. Moscow’s record for dealing with people who don’t toe the official line is not a happy one. Their defence against officialdom is not strong. “Place sin with gold,” says King Lear in the eponymous play by William Shakespeare, “and the strong lance of justice hurtless breaks. Arm it in rags, a pygmy’s straw does pierce it.”

The opening session of the court was held behind closed doors because of the corona virus scare, although that’s not the reason for the hearing to have been suspended. It’s the sheer volume of the evidence: 36,000 pages of files and other material; Pulatov’s lawyer, the only defence figure taking part in the proceedings, told the court he needs time to study everything. The judge agreed. “The court suspends the examination of the Pulatov case until June 8th, 10am,” said Presiding Judge Hendrik Steenhuis, “and the defence will be able to speak at that time.” Supporters of the victims’ families placed 298 empty chairs outside the Russian embassy in the Hague as a reminder of those who died, many bearing white roses and photographs of the dead. Embassy officials declined to comment but Putin, while saying he would await the outcome before giving his opinion, cast doubt on the likely objectivity of the trial, saying the evidence gathered is ‘biased and politically motivated’. Although none of the accused is expected to appear – Russia never extradites its citizens and even though Kharchenko is a Ukrainian citizen, it’s thought likely he now holds a Russian passport – relatives of the victims believe the trial could bring some comfort to them. Justice in this case is not only delayed but looks likely to be denied altogether. Those who lost loved ones, though, still see it as more than just symbolic. Meanwhile, Girkin and Kharchenko have been placed under a visa ban and had their assets frozen by the European Union, which has also imposed asset freezes on several Ukrainians who held positions under the pre-2014 regime and who stand accused of ‘looting the country’. Ukrainian investigators are still assembling cases against them. And of course, being accused and standing trial, even if in absentia, as in this case, is no proof of guilt.

So now the case is there but not there, like the missing dead who might have filled those chairs in The Hague. It will continue, but it may take years, and those who caused the disaster will doubtless walk free, untouched and untouchable. Westerbeke, in his opening speech, quoted the Russian writer Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, who once said “Violence has no way to conceal itself except by lies, and lies have no way to maintain themselves except through violence.” The war in the Donbass region goes on, despite a ceasefire and a ban on certain types of weapon. On one day, 8 April, the ceasefire was reportedly violated eight times and Ukrainian forces near the town of Maryikna and villages such as Pavlopil, Hnutove, and Novo-Oleksandrivka, came under attack from troops firing 120mm and 82mm mortars – both supposedly outlawed – as well as from heavy machine guns and small arms. So the conflict is not over, despite a peace conference in Paris last December, mediated by France and Germany, and despite new Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelensky agreeing to a 2016 formula that gives special status to the Donbas region.

Some 13,000 people have died in the conflict, not counting the passengers of Malaysian Airlines flight MH17. The Dutch court is determined to ensure that their deaths will count, or at least come under detailed scrutiny, however obliquely. It will focus attention, whether or not the accused are found guilty, but in view of the current media obsession with the corona virus, justice looks like being delayed, denied and, unfortunately, largely ignored.

However, the hearings related to the trial that began on 9 March 2020 continued, and on 25 November of the same year, the District Court of The Hague made what is known as an interlocutory decision, which also marked the conclusion of the pre-trial stage in the proceedings.

The point of such a decision is generally to allow a case to progress unhindered by addressing, for example, an issue that otherwise would cause the case to stall.

In the case at hand, the interlocutory decision comprises rulings on all requests for investigation submitted by the defence as well as the Public Prosecution Service at previous hearings.

Consequently, Judge Hendrik Steenhuis rejected the request by the defence for more time to investigate alternative explanations for the shooting down of flight MH17. The defence repeated a previously submitted request to retrieve information from devices that may have recorded radar activity and also wanted to be given access to additional photographs of the wreckage. These were also rejected by Judge Steenhuis who said that a clear alternative scenario had not been presented. The Court also called for new questioning of the witnesses and reiterated its wish to hear the four suspects in person.

The three Russians, Pulatov, Girkin and Dubinsky as well as the Ukrainian suspect Kharchenko have not cooperated with the court so far. The case was then referred to the examining magistrate for additional investigation. Due to the numerous delays caused by the Covid-19 pandemic, the hearings only resumed on 1 February 2021. Among the issues addressed were the progress of the additional investigation, the damage claims submitted by the victims’ relatives and the official request by the Public Prosecution Service to inspect the reconstruction of the remains of the plane. At this hearing, Oleg Pulatov’s lawyer, Sabine Ten Doesschate requested that an expert from Almaz-Antey, the Russian state-owned arms manufacturer be also allowed to inspect the reconstituted wreckage of the plane.

The Court convened again one week later, on 8 February 2021. During this session, Judge Steenhuis announced that the Court did not believe it to be necessary to allow an expert from Almaz-Antey to inspect the debris, stating : “The court considers that enough consideration has been given to the usefulness and the need to establish the expertise of the witnesses or experts, and the understanding or assessment of those documents. Both requests from the defence, because of a lack of an established need, have been denied “. In addition, the defence’s request that two new witnesses be interviewed was rejected by the Public Prosecution Service on the grounds that the information available about these witnesses was insufficient.

The Court also confirmed that if the decision to allow an inspection of the wreckage is approved, the number of people able to attend will be limited, for two reasons. Firstly, the reconstructed remains of the plane are in a relatively small hangar situated on a secure, military site. And secondly, Covid-19 measures may still be in place at that point in time. In the event of an inspection, it has been decided that a livestream coverage will be provided by the Court. Regarding claims for damage compensation, the Court had, on 31 August 2020, determined that for the time being, such claims that are yet to be submitted by the victims’ relatives shall be subject to Ukrainian law. A law firm in Ukraine was asked by Counsel for the Relatives, to cooperate with a professor of Ukrainian law in providing adequate legal advice. Furthermore, it is expected that all claims for compensation will be submitted by 15 April 2021 at the latest. This is the date of the next hearing, during which it will be decided whether to allow the inspection of the wreckage. If the Court approves the application, this will be conducted in May 2021.

The date of 7 June 2021 has been set as the start of the hearing on the merits in the MH17 criminal trial, if the investigation by the examining magistrate proceeds as expected.

This is the main phase of the trial and as its name suggests, a hearing on the merits is one in which one side presents to the judge the facts which support their side of a case or ruling. Conversely, the other side will attempt to prove that the proponent’s case has no merit.

It is expected that the relatives of the victims of flight MH17 will be able to exercise their right to address the court sometime after the summer of 2021.

No definite date has been set for the conclusion of the criminal trial.

But it must not be forgotten that besides Pulatov, Girkin, Dubinsky and Kharchenko as the suspects, the Russian Federation as a state is also being prosecuted, in particular under the Terrorist Financing Convention, following Ukraine’s lawsuit against that country in the International Court of Justice.

The Joint Investigation Team (JIT) continues its work and additional charges cannot be ruled out, while at the hearings in the UN International Court of Justice, Russia has made attempts at delaying the transition to the consideration of merits, citing Covid-19 and other difficulties in formulating its legal position.

By all accounts, it is expected that the International Court of Justice will hand down a final ruling on the MH17 case by late 2023.