Lines of cocaine © Wikimedia

You may not know what it means to have a woolie or a lucy or to be offered a wrap. If, however, you were in the chokey, it would soon become clear. Of course, you could be taking a bang with a booshwa. It’s all prison slang, as used in UK prisons, at least, especially in the area surrounding Birmingham in the British West Midlands. Most countries have their own versions. In the UK, a ‘bang’ is an injection and a ‘booshwa’ is a syringe. ‘Rails’ are lines of cocaine, ‘woollies’ are marijuana cigarettes laced with cocaine, while a ‘lucy’ is LSD (presumably from the old Beatles song about the drug, Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds). A ‘wrap’ is the sort of small quantity of drugs sold by street dealers in small paper or foil packets, often bought by youngsters, some of them not yet in their teens.

Heroin, also known as ‘smack’ is made from morphine, derived from the opium poppy. The ‘slammer’, of course, is the prison itself, but it could also be called the ‘chokey’ (from an early 17th century Anglo-Hindi word, caukī), while serving time there is ‘doing bird’. There are many other expressions in use by the prison’s inmates but quite a few of them don’t really bear repetition in a respectable journal. There’s also the ever-present risk that you may suffer ‘kwef’ (violence), possibly a ‘bagging’ (stabbing in the lower body) which could turn into a ‘dupying’ (killing) if you’re not careful. And if you turn out to be a ‘snitch’ (informer), somebody may ‘nank’ (stab) you. Not pleasant places, prisons, according to a few old gaolbirds I’ve met, none of whom seemed keen to go back ‘inside’, although few of whom took the logical step of ‘going straight’ (staying within the law) in order to avoid the risk of a penal sentence. On one of my reporting jobs, I was hosted for tea and biscuits, along with my cameraman and sound recordist, in the Turkish prison of Nevşehir, in the picturesque and very historic region of Cappadocia.

In one large cell, there were three prisoners acting as our hosts. One of them was clearly the ‘leader’. He had been a major drugs dealer in the Netherlands. The youngest of the three went down to an underground kitchen to fetch our refreshments, which we drank and ate in cheerful conversation with the prisoners, via an interpreter. Later, I asked the prison governor what crimes had got them into prison and it turned out that the one who had made our tea and brought our biscuits was a notorious poisoner, doing time for murder.

According to the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA), on any normal day in Europe there are some 856,000 people serving prison sentences. Across the globe in 2019, the figure rose to 11-million people, but I’m going to concentrate on Europe. In this context, Europe includes the 27 member states of the European Union plus Norway, Turkey and the UK. Most of them have experienced higher levels of drug abuse before they were caught and sentenced, mainly heroin, cocaine and amphetamines. Prison doesn’t stop them from taking drugs, although it very often stops them from taking precautions. For instance, people who would never choose to share a hypodermic needle under normal circumstances may find they have little choice if they want to ‘shoot up’ with something chemical (also dangerous and highly illegal) in prison. As a result, the spread of infectious diseases is likely to increase.

The EMCDDA report points out that: “The lifetime prevalence of substance use before and during imprisonment varies by country and is influenced by differences in prison organisation, drug policy and drug use prevalence in the community, as well as differences in survey methodology. Women in prison are reported to be particularly vulnerable and at risk of problematic drug use.” In fact, according to research by Medcraveonline.com, more than 40% of women admitted to prison already had a drugs problem, compared with only around 26% of men. A relatively smaller proportion of both genders developed their addiction inside prison. The EMCDDA report highlights a particular challenge in recent years: the increasing use of new psychoactive substances in prison, particularly synthetic cannabinoids. “The initial undetectability of these substances in routine urine testing is thought to be a main contributing factor”, it says.

A wide variety of methods have been tried in a bid to cut down on drug use and drug availability in prisons. Expert groups have examined the scale of the problem, assessing the scale of the problem within the prison population, giving advice and health warnings to prisoners, pharmacological treatments, making opioid substitutes available (it’s called opioid substitution treatment or OST), as well as tackling infectious diseases spread through drug use. It’s an uphill struggle. You would be excused for believing that a prison is such a tightly controlled environment that it would be difficult to smuggle things in, but the dealers, pushers and friends of inmates can be very creative.

In the UK, drones are a popular method. In 2016, seven people were charged with smuggling drugs with a street value of £500,000 (more than €580,000) into prisons all over the UK. The gang had made some 55 deliveries using drones in what police described as the biggest drone delivery system they had ever uncovered in Britain. The seven involved are now serving prison time themselves. Less technically creative gangs have been known to use large catapults to get their contraband over the wall. Drones have the advantage, however, because gangs can use them to ship not only drugs but also mobile phones and other items to their friends inside. In New Zealand, drugs were discovered inside the bodies of dead birds that friends of certain inmates had thrown over the prison yard wall. In the United States, with its religiously-inclined population, one inmate was sent a bible, which may or may not have aided his devotions.

The bible’s pages had been soaked in sufficient heroin for up to 40 ‘hits’. Prison guards spotted that the pages were stained and thus uncovered the subterfuge. The man would presumably pray for a mild punishment.

NO HIDING PLACE?

What about ‘all-white bricks’, ‘nose whiskey’ or ‘white chalk’? They’re all slang terms for cocaine and demand for it is high inside It can involve different words and phrases, according to The Children’s Society in the UK, who asked youngsters from the Birmingham Disrupting Exploitation Programme (BDEP) to bring them up to date on currently popular drugs slang, and I should mention that words well understood in Birmingham, Wolverhampton and Coventry may be quite different from those used in, say, Glasgow, London or Newcastle, and certainly different from similar terms in Chicago, Paris or Bratislava. However, cocaine (and other substances forbidden to prisoners) can also be called ‘chicken’, which strictly speaking means a kilo of cocaine.

In some places, it means a kilo of crack cocaine, with a kilo of ordinary raw powdered cocaine being known as a ‘bird’. Elsewhere, ‘flippin a chicken’ means buying a kilo of ordinary cocaine and cooking it up to turn it into crack, which also increases its weight and volume. So how do you get that inside? One solution is known as ‘bottling’: hiding the drug in a container which is then concealed up the carrier’s vagina or anus (although drugs hidden in one’s anus are known in the UK’s West Midlands as ‘kester plant’. It’s done in the United States, too, where a Michigan woman was found to have 80 prescription drugs hidden in her vagina. The person doing the carrying is usually called a ‘mule’. Back in the US, the very helpful website ‘DrugAbuse.com’ cites the case of three New Jersey prisoners who dissolved Suboxone, which is a strong analgesic used as an opioid substitute by addicts, into a paste they subsequently painted into a colouring book with “to Daddy” written on the cover. Prison authorities recognised what it was straight away and confiscated it. Not all of these tricks work in the prisoners’ favour, either. In Kentucky, one prisoner who was out on remand, returned to custody with underpants soaked in methadone. He overdosed on it and died. However, prison visits are still the source of many of the drugs smuggled inside to inmates.

In a report prepared for the Medcrave website (Medcraveonline.com), Andrew O’Hagan and Rachel Hardwick of the Department of Science and Technology at Nottingham Trent University in the UK, point out that the trade is not exactly altruistic. Some people may try to help a friend or relative inside but the main motive, as in so many things, is money. “A good example is the case of Charlotte Millward, a 35-year-old mother of two,” O’Hagan and Hardwick write, “who was seen reaching inside her undergarments and handing 10 tablets to her boyfriend during a visit at Holme House Prison in 2014. The tablets, worth around £2 each (€2.33) outside of prison, were worth £40 (€46.7) inside the prison. For this offence, Charlotte received a six-month suspended prison sentence.” Of course, prisons do use sniffer dogs to detect suspicious packages, but drugs that give off an odour are often smothered in Marmite, the yeast-based vegetarian food spread popular with vegetarians but hated by some. It has a strong smell that can cover the smell of some drugs. The ingenuity of the smugglers is impressive. For instance, report O’Hagan and Hardwick, drugs can be sprayed onto otherwise innocent-looking paper, such as children’s drawings. “In a Scottish Prison, inmates are no longer allowed to receive their children’s artwork or drawings,” reads their report, “after an incidence when powdered Valium was found in the paint. Staff at HMP Shotts in Lanarkshire found the Valium had been painted onto the artwork which inmates would cut up and eat.” The drug known as ‘spice’, which is synthetic cannabis, can be sprayed on to children’s drawings and then smoked. It is not detectable by X-ray, nor by smell. Inside prison, one sheet changes hands for approximately £50 (€58.3).

Prison staff are not above suspicion, either. One officer was given £1,000 (almost €1170) for slipping an ounce of crack cocaine past his fellow-guards, whilst another received £500 (almost €584) for bringing in a package that contained whatever the recipient had ordered from outside, including drugs and mobile phones.

Staff have even helped prisoners to run a £30-million (€35-million) drug dealing operation from inside their cells. In Wandsworth Prison, in South West London, prisoners made use of computers provided by Britain’s Ministry of Justice, linking them to internet sites, along with mobile phones provided by guards, and put £30-million (€35-million) of illicit drugs onto the streets of London between 2010 and 2013. Rehabilitation of offenders is made harder by their dependence on drugs.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) in Europe reminds us that: “According to data from the Council of Europe, about 635,000 people were estimated to be in penal institutions in the 28 EU member states and Norway on 1 September 2010.” Its website explains the figures and what they mean in terms of actual people: an average of 135 prisoners for every 100,000 population in European states. The rates are different, though, in different countries. “It ranges from 60–70 per 100,000 population in Denmark, the Netherlands, Norway, Slovenia and Sweden to over 200 in the Czech Republic, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and Poland. This figure is lower than in some large countries, for example 620 in the Russian Federation and 740 in the United States.” It explains why Johnnie Cash got the blues in Fulsome Prison, anyway.

Cannabis is still the commonest drug of choice among life-long users who have ever taken an illicit drug, ranging from 12% to 70% of prisoners who’ve tried it. It’s also still the most popular drug among the public at large, although rates are lower than those that pertain in prisons, with 1.6% to 33% among people aged 15 to 64. The popularity of cocaine depends on the country where it’s used: 6% in Romania to 53% in Spain. Among the wider public, cocaine use ranges f rom 0.3% in Malta to 10% in Spain. According to EMCDDA data, “Lifetime prevalence of heroin use among the prisoners who have ever used any illicit drugs ranges from 8 to 39%, with 8 out of 13 countries that were able to provide information reporting levels in the range 15 to 39%.

Amphetamine experience among prisoners ranges from 1% to 45%, whereas among the general population, the range is from 0% to 12%.” The EMCDDA also gives us a timely reminder of a societal fact in its report that we would do well to bear in mind: “Drug users form a large part of the overall prison population, with studies showing that a majority of prisoners have used illicit drugs at some point in their lives and many have chronic and problematic drug use patterns. Because of the illegality of the drugs market and high cost of drug use, which is often funded by criminal activity, the more problematic forms of drug use are accompanied by an increased risk of imprisonment.”

HELP NO-ONE ASKS FOR BUT GETS ANYWAY

Many countries have run schemes aimed at weaning the prison population off narcotics and the Pompidou Group of the Council of Europe has seen some positive results, one of which is quoted on the Group’s website: “Since I turned 13 years old, I used to turn off my feelings by using drugs, I turned off my fears. I was just taking drugs and living in my own world. Now I feel very well, I started feeling emotions that bring me joy and make me happier.” So said a resident at the in-prison Therapeutic Community in the Republic of Moldova.

The Group also reminds us that: “People who are incarcerated often come from poor and deprived segments of the population and include migrants, ethnic minorities, people without employment, people with substance use disorders or sex workers. Many diseases concentrate in these vulnerable and underserved groups.” I could point out another disadvantage that too many of them suffer: they get very little sympathy from the wider public, making medical and psychological interventions harder to apply. “People who are detained are often subject to stigmatisation due to their dependence. The fear of being caught for drug possession, as well as backlash from other inmates often prevents drug-dependent detainees from seeking help or complying with their drug treatment.” Progress may be relatively slow but it is still progress. “The first in-prison Therapeutic Community in the Republic of Moldova was officially opened in Pruncul prison in November 2018. Today, “Catharsis” is home to 25 residents coping with drug problems, who are learning skills there that will help them to live a healthy and stable life after release from prison.”

Europol, the EU’s cross-border law enforcement agency, has reported that the drugs market in Europe as a whole has been changing and not just in its prisons. “Organised crime benefits significantly from the drug trade,” reads a Europol report on the issue, “but more worryingly, these criminals have shown determination and ruthlessness in trying to grow their market share. The direct impact of these developments is to be found in the number of fatal drug overdoses, of which there were 8,238 in the EU in 2017, and individuals seeking help from treatment providers or emergency services.” Research suggests that the issue of drug addiction is getting worse. “In Germany, prison sentences for drug offences rose from 10.8 percent in 1971 to 31.5 percent in 1976,” wrote Sonja Snacken and Kristel Beyens in the European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research back in 1994; “in the Netherlands the proportion of prison sentences for drug offences is six times higher than the average.”

The scientific skills of the drug criminals has been becoming more sophisticated, too. In Hungary, there has been a large increase in the numbers injecting new psychoactive substances (NPS), according to a 2016 report in Science Direct. This coincided with decreasing efforts at harm reduction and rising cases of HIV infection. The article concludes: “NPS injectors in Hungary are at severe risk of blood-borne infections due to high levels of injecting and sexual risk behaviours within a high-risk environment.” The EU has funded projects aimed at reducing the damage done through taking drugs, often including drugs of dubious provenance and purity, for several years.

“The Joint Action on HIV and co-infection prevention and harm reduction (HA-REACT) project, which took place between 2015 and 2019, addressed existing gaps in the prevention of HIV and other co-infections, especially TB and viral hepatitis, among people who inject drug,” the EMCDDA explains in its report on the latest drug reduction programme.

“Among the areas covered by the project, prison health is central. One of the HA-REACT project’s outputs, a toolbox on how to advance harm reduction in prison settings, is available on a dedicated web platform (hareact.eu). Among the tools available are information, education and practical implementation materials targeting healthcare professionals operating in prison settings, prison administration and other relevant stakeholders (e.g. community-based organisations): materials are oriented towards implementing interventions such as OST and prison needle and syringe programmes, condom distribution and provision of take-home naloxone.” Whilst addressing the issue of drug taking inside prisons, nobody seriously imagines a route out of the problem that will ever eradicate it altogether. In any normal society, money is the most effective motive, but when prisoners are prepared to pay many times the street price for narcotics, (remember prisoners paying almost €47 for drugs selling outside for €2.33?) it doesn’t seem to work in this case. It all comes down to supply and demand. In prisons, the demand is huge, while the supply, despite the efforts of gangsters, family members and corrupt guards (known as ‘screws’ in UK slang) is limited, and the toughest prisoners, by and large, control access.

KNOW YOUR OFFENDER

The actual prison population varies across Europe, although there are some common factors. Women represent around 5% of the prison population (around 41,000), varying from 3% in Bulgaria to 5% in Cyprus. According to the EMCDDA, the prison population has an estimated mean age of 37 years, ranging from 33.6 years in Denmark to 41 in Italy. “An estimated 11% of people in prison in Europe are foreign nationals, with considerable national variation — from 0.2% in Germany to 74% in Luxembourg,” says the report. “Around one fifth of people in prison have not received a final sentence, ranging from 8.4% in Czechia to 48% in Luxembourg.” The report also explains other essential facts about the European prison population. “More than half (52%) of people in prison are sentenced to 5 years or more, with 37% sentenced to between 1 and 5 years and 11% sentenced to less than one year. The main offences for which people are given prison sentences are property crimes such as theft and robbery (32%), drug offences such as possession and trafficking (18%) and homicides (12%).”

Whatever the crime, though, prisoners are supposed to be treated alike. According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), the health of prisoners is an important matter. “In 1995 the WHO Regional Office for Europe set up the Health in Prisons Programme (HIPP) to encourage and support WHO Europe countries to address the higher prevalence of health problems in prison. Since its inception HIPP has developed to become a crucial international movement to promote health in prison settings. HIPP’s main activity is to give technical advice to member states on the development of prison health systems and their links with public health systems and on technical issues related to communicable diseases (especially HIV/AIDS, hepatitis and tuberculosis), illicit drug use (including substitution therapy and harm reduction) and mental health.”

The EMCDDA admits that data on access to drugs in prison are scarce and frequently based on anecdotal information. This lack of factual data, now and in the past, means it’s virtually impossible to track trends in drug use among prisoners. It’s worth remembering, however, that many of the crimes that landed people in prison were to fund a pre-existing drug habit or else were committed while under the influence of drugs. People in prison are far more likely to have used drugs and to have to used them regularly, including suffering drug-related problems, than other people in the community. Worldwide, it has been estimated that 30% of male prisoners and 51% of women have some sort drug use disorder. At European level, studies have shown that between 30% and 75% of people with problematic drug use have been in prison at some time in their life. The high prevalence of drug use among people in prison reflects, and is reflected in, a number of social factors. For one thing, nobody likes or wants to be in prison and if they cannot get out any other way, at least drugs allow them to escape in their minds.

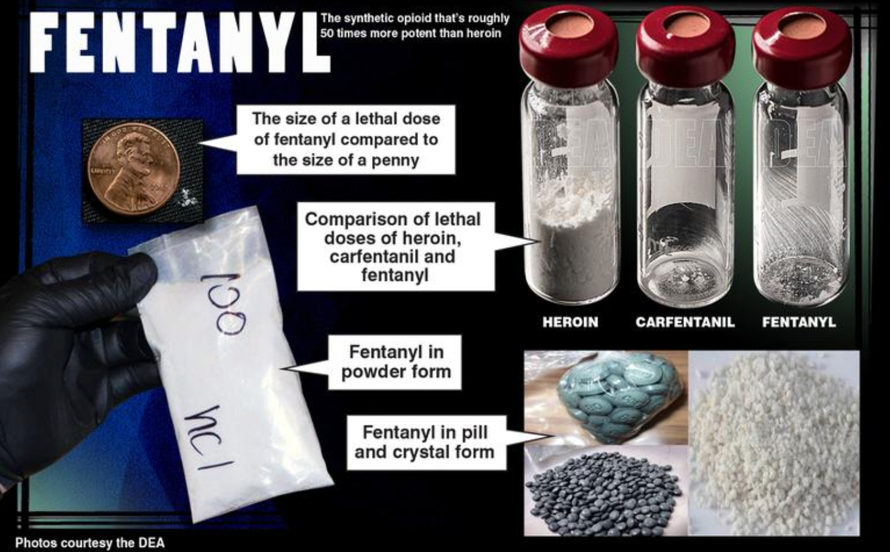

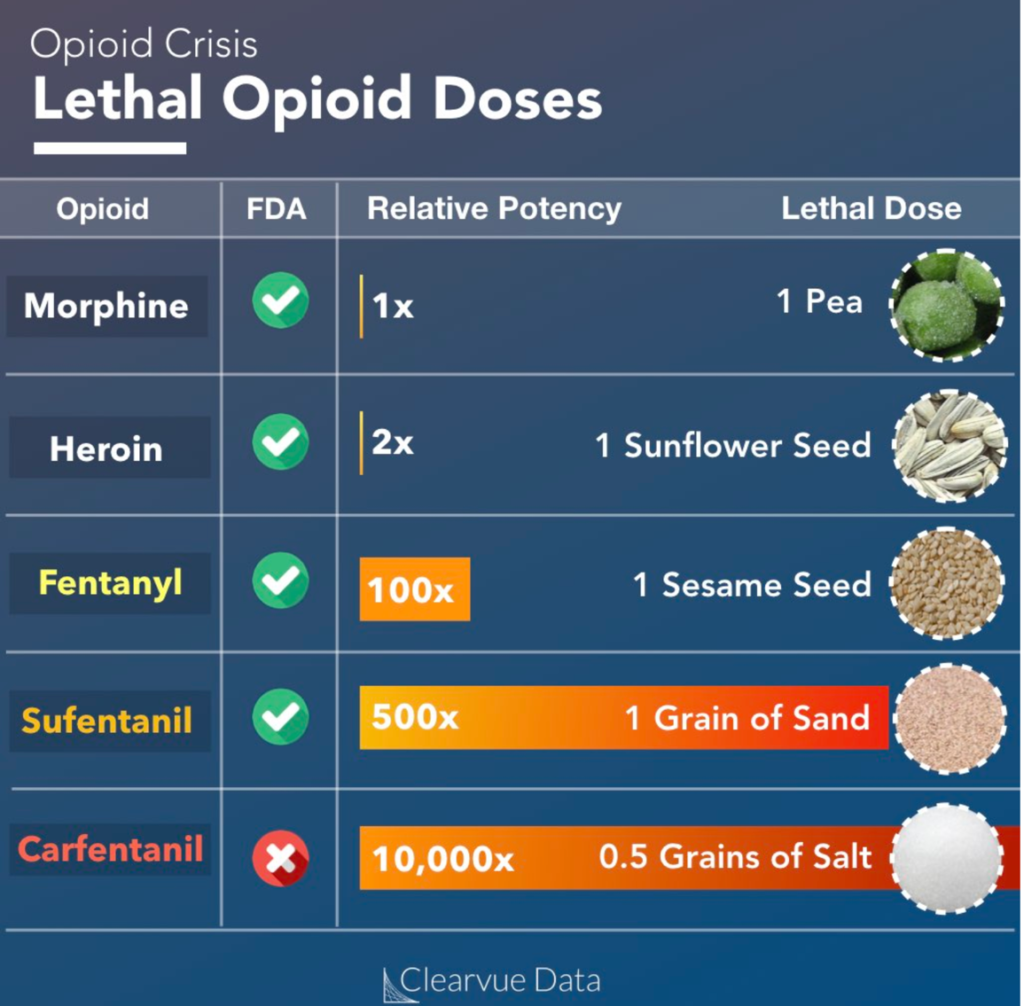

Sometimes, of course, it’s an escape route that can prove permanent: there were 8,238 fatal overdoses recorded in the EU in 2017, according to Europol. For Europol, the switch to the kinds of narcotics that can be cooked up in somebody’s basement laboratory is making the job of policing their use harder. “Problems attributable to synthetic cannabinoids appear to be growing,” says Europol’s 2019 report, “as their relatively low cost, easy availability and high potency are factors in increased use among marginalised groups, including the homeless and prison populations. In addition, new synthetic opioids are a growing cause for concern, with a rapid increase seen in the number of fentanyl derivatives, substances particularly associated with health problems, including fatal poisoning.” Fentanyl is a narcotic analgesic with a potency at least 50 to 100 times that of morphine. No wonder it’s popular, although despite its undoubted power, its effect is short-lived: just 15 minutes or so, compared with 45 minutes for morphine, although fentanyl’s effect on respiration can outlast its analgesic effects. With a little skilled tweaking of the fentanyl formula, it can be turned into carfentanyl, which is supposedly 10,000 times as potent as morphine. That might gain the user a considerable escape from reality.

The alteration to the drug would have to be carried out by a very skilled biochemist, however, although it seems that Europe’s drug gangs can easily afford such expertise.

A Fentanyl analogue known as “china white” (α-methylfentanyl) was first reported in California in 1979. In 1984, another illicit designer drug, 3-methylfentanyl, appeared as a street drug in the state, and it also became linked to fatal drug overdose. Three deadly poisoning cases involved 3-methylfentanyl. Fentanyl and its derivatives (Alfentanil, Sufentanil, Remifentanil and Carfentanil) are used as anaesthetics and analgesics in both human and veterinary medicine (Carfentanil). They are subject to international control as are a range of highly potent non-pharmaceutical fentanyl (NPF) derivatives, such as 3-methylfentanyl, synthesised illicitly and sold as ‘synthetic heroin’, or mixed with heroin. Mixing it with heroin would make it an extremely potent narcotic and hard to break from if ever a user should become addicted to the stuff.

The variants, like fentanyl itself, are usually administered intravenously in single doses. Originally, its short period of action on (and in) the body was thought to be the result of its rapid removal from the body. However, as clinical experience increased, it was realised that if multiple or larger than normal doses were used during narcotic-based anaesthesia, it sometimes led to delayed recovery and prolonged respiratory depression, suggesting that the action’s duration was limited by redistribution within the body rather than removal from it.

The National Library of Medicines writes that: “Renal excretion accounts for up to 10% of the dose; the remainder of the clearance would appear to be predominantly hepatic, but with contributions from other tissues. Continued clinical developments of narcotic-based anaesthetic techniques have resulted in high doses of narcotic being used, with oxygen, as the sole anaesthetic agents.” At present these techniques are usually based on fentanyl, and the technique is frequently called ‘stress-free anaesthesia’ because of the effects in reducing the sensitivity of tissues in the target area, the ‘stress response’ caused by surgery (elevation of plasma concentrations of cortisol, glucose, ADH, etc. in the intra- and post-operative period) and the lack of deleterious effects on the cardiovascular system.

ONE CRIME LEADS TO ANOTHER

As well as its effect on the health of inmates, criminals often use drugs to establish their authority within the prison system ‘pecking order’. This leads inevitably to assaults, blackmail and quite a lot of violence, not just between prisoners, but also against prison staff. The medcraveonline.com report points out that: “Violence protects the credibility, profits and reputation of their (the drug dealers’) business. Inmates are hired to accumulate payments and intimidate, threaten and be physically aggressive towards debtors.” The result is perhaps not so surprising: the most ruthless and violent prisoners rise to the top, to run certain prison ‘wings’ as their private fiefdoms, and to control their fellow inmates, organising riots, for instance, to help facilitate an escape. They have also been known to force weaker, more vulnerable prisoners to take drugs (and pay for them, of course) in order to create a drug dependency and hence a reliable source of future income.

Prison drug dealing is not without a financial cost for the authorities, too. “European countries have an estimated expenditure in the range of €3.7-billion to €3.9-billion on drug law offenders,” says Medcraveonline.com. “Drug related crime cost England and Wales £13.5-billion and the CJS (Criminal Justice System) budgeted over £300-million (€350-million) in 2006/07 for adult drug interventions. Specifically, prison treatment in England and Wales has increased from £7-million (€8.17-million) in 1997/98 to £80-million (€93.36-million) in 2007/08.” The violence is not confined to inter-prisoner relationships behind bars but it also extends to debts being enforced on the prisoner’s friends and families on the outside. Additionally, profits from drug supply in prison are often used to fund criminal activity out in the wider community. Even so, treatment programmes for prisoners’ drug problem only really started to be addressed as fears arose over HIV/AIDS, which are often spread by shared needles, as well as by sexual activity.

It all presents a massive problem for prison authorities. Mandatory testing would seem like a good idea, but it encourages a switch from soft drugs to harder ones. Heroin, for instance, only stays in the system for up to three days, whereas the use of cannabis can be detected for up to 14 days. It means that heroin is the safer choice, in terms of being caught out. Watch towers and a German-made drone detector are one solution that is attracting support, while a single sniffer dog at the UK’s Wandsworth Prison, near London, found concealed drugs with a street value of £300,000 (€350,000) in a single year. Working out how to reduce the ingress of drugs into prisons is one solution, but it involves having to stay constantly ahead of the gangsters and their associates on the inside; a kind of narcotic arms race, if you like. It seems unlikely to end any time soon, either.