© EDM

Launching a war of aggression is one of the riskiest steps any political leader can take. Sixteen months after Russia’s brutal invasion of Ukraine, President Vladimir Putin is facing the consequences of his reckless gamble. The war has exhausted the power and stability of his regime, and Russia’s repeated military failures on the ground, as well as the high number of casualties and increasing economic hardship, have put his regime in grave danger.

The Russian invasion has also exposed the Kremlin’s incompetence, corruption and poor governance. The war threatens to undermine Putin’s legitimacy itself. The Kremlin has spent more than two decades modernising its military with huge investments and under the supervision of the president, but the performance of the Russian military has been disappointing.

Prigozhin’s uprising – or coup attempt – is a real turning point for Russia and its president. It poses an unprecedented threat to Putin’s power and, more importantly, to Putinism – Putin’s personal system of semi-totalitarian state control. The consequences of recent events will be felt across Russia in the months and years to come, whatever the outcome.

Russia’s enemies were to be found in the West. Now the greatest danger to Russia and Putin comes from Russians within. The narrative justifying the war against Ukraine is coming apart at the seams.

On Friday, 23 June, armed paramilitaries under the leadership of Yevgeny Prigozhin — the former convict cum caterer, turned commander of the Wagner Group — launched what very much looked like a coup against Putin’s regime. At the height of the action, troops under Prigozhin’s command first captured the strategic city of Rostov-on-Don and then barreled towards Moscow.

His men had fought the toughest battles of the 16-month Ukrainian war, including for the eastern city of Bakhmut. For months, he had railed against the military’s top leadership, especially Defence Minister Sergei Shoigu and Chief of Staff Valery Gerasimov, accusing them of incompetence and withholding ammunition for his fighters.

In June he resisted orders to sign a treaty placing his troops under the command of the Defence Ministry.

He began the apparent mutiny on Friday, 23 June, after claiming the military had killed many of his fighters in an air strike. The defence ministry promptly denied this accusation.

He said he had taken control of the headquarters of the southern Russian military district in Rostov, which serves as the logistical centre for the entire Russian invasion force in Ukraine, without firing a shot. The nearby area is also a major oil, gas and grain region.

Residents of the town had been calmly walking around filming with their mobile phones while Wagner fighters in armoured vehicles and battle tanks occupied positions.

Wagner’s rapid insurgency seemed to proceed without significant resistance from the regular Russian armed forces, casting doubt on Putin’s grip on power in the nuclear-armed country, even after Wagner’s advance came to a sudden halt.

Only after Wagner motorised columns reached the city of Voronezh, about 500 kilometres from Moscow did a Russian helicopter gunship attempt to attack them with rockets. According to some reports, a fuel depot exploded in a fireball and one of the helicopters was shot down.

Earlier, Prigozhin had called for a “march for justice” to depose corrupt and incompetent Russian commanders whom he blames for the failure of the war in Ukraine.

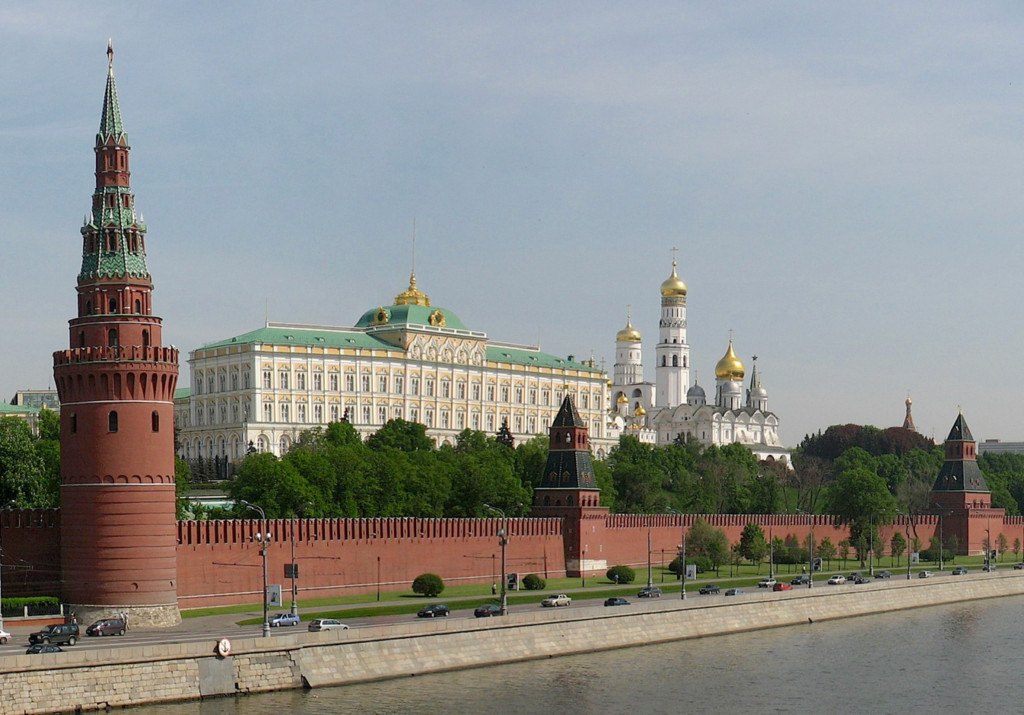

In a televised address from the Kremlin, Putin had earlier said that the Wagner uprising was endangering the very existence of Russia.

“We are fighting for the life and security of our people, for our sovereignty and independence, for the right to remain Russia, a state with a thousand years of history,” Putin said, promising punishment for those who “planned an armed uprising”.

But in an extraordinary turn of events, Prigozhin reportedly turned his troops around late on Saturday, 24 June, following a negotiated settlement, but it was the first major crack in the president’s armour.

A notable feature of the rebellion and the ensuing chaos was the apparent peacemaking role of Belarusian leader Alexander Lukashenko. The Kremlin claims that Yevgeny Prigozhin surrendered, that his troops stopped their advance on Moscow, and that he agreed to relocate to Belarus after speaking directly with Lukashenko. However, welcoming the renegade commander into Belarus could be dangerous for Lukashenko.

Although Belarus was one of the bases for Putin’s war in Ukraine, and Russian missiles were launched from Belarusian airspace, Lukashenko managed to avoid sending Belarusian troops to fight in Ukraine. Now it may become more difficult for Lukashenko to stay out of the war or out of the political crisis in Russia.

By relocating to Belarus, Prigozhin will effectively be based abroad, but easily accessible to Russia. So, this can also be seen as an act of revenge by the Kremlin. Putin’s promise to strengthen the police, helped secure Lukashenko’s power in 2020, when massive protests against his re-election – widely condemned as rigged – threatened to topple him.

Lukashenko’s fate thus seems closely tied to Putin’s – he is one of the few foreign leaders Putin can trust, and Belarus, like Russia, is subject to extensive Western sanctions. Lukashenko’s harsh, decades-long authoritarian rule is similar to that of Putin. Both follow the intolerant conservatism and militarism of the Soviet era. But the fact that it was the Belarusian “little brother” who stood by his Russian “big brother” in his time of need looks embarrassing to Putin.

Belarusian opposition leader in exile, Svetlana Tikhanovskaya, called Prigozhin a “war criminal” and said that his move to Belarus would “increase instability” in the country. Tikhanovskaya, in remarks quoted by the independent Belarusian news website Zerkalo, said her country did not need “more criminals and thugs” and added that Belarusian leader Alexander Lukashenko was ‘not a mediator but a courier” when he arranged a deal between Moscow and Prigozhin. “He was Putin’s emissary” she said, arguing that this was to avoid embarrassing the Russian president. “The world has seen that Putin is not invincible ,and not that strong. A weak Putin means a weak Lukashenko” she added.

She further accused Alexander Lukashenko of making Belarus a “pawn in other people’s games and wars”. Tikhanovskaya left Belarus in 2020 after challenging Lukashenko in an election that she was widely seen to have won. She was later sentenced in absentia to 15 years in prison by a Belarusian court.

| The end of Wagner?

Yevgeny Prigozhin said in an audio message released on his Telegram channel on 26 June that Wagner’s aim was not to overthrow the Russian government but to protest against the abolition of the private military company and to draw attention to the failures of the Russian military leadership in Ukraine.

The mercenary group had not wanted to fight the Russian military and had only fired on Russian troops and a helicopter after they had attacked the Wagner fighters from the air.

Prigozhin also pointed to the fact that Wagner columns advanced to around 200 kilometres of Moscow without any military resistance, highlighting the disarray in the defence ministry.

According to Prigozhin, his troops had held a “master class” in how Russian forces should have taken Ukraine when they invaded in February 2022. He said that he ordered his troops back only so that no Russian soldiers would be killed or injured.

In the meantime, it is uncertain whether the Wagner Group will be disbanded and what impact such a move might have in Ukraine and other places where Wagner mercenaries have operated. Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov has since announced that authorities would drop charges of “inciting armed insurrection” against Prigozhin and that Wagner forces who joined the march would also not be prosecuted. The Kremlin added that Wagner fighters who did not join would be able to sign contracts with the Russian defence ministry.

But whether Russia can afford to dissolve the Wagner Group was not immediately clear. The mercenary group did after all, help the country make profits in its war against Ukraine and was responsible for the much-publicised capture of the Ukrainian town of Bakhmut in May 2023. There are also those who believe that the Wagner Group allows Putin and other officials to deny the mercenaries’ losses, and that by hiding them Russia can hide the true cost of the war. In fact, since 2014 they have remained Russia’s weapon of choice.

Prigozhin, however, differs from other political rivals of Putin who have criticised the country’s leadership, because he has a powerful army at his back and it is not uncommon for mercenaries to incite rebellions against the governments that have hired them.

Prigozhin is something of a Frankenstein monster that Putin has created for himself, with the Wagner Group that acted as a de facto force of the Russian state, but which was more independent than the military.

The Russian president may, at first, have thought that it may not be easy to disarm and disband the Wagner Group. The question would always remain: Will they cooperate and act in concert with the Russian military leadership to pursue Putin’s military objectives in Ukraine?

Prigozhin and Wagner have not completely disappeared, but in an important development on June 27, the defence ministry announced that preparations were under way for the Wagner Group to be disarmed, handing over their heavy weapons to the Russian armed forces.

The FSB security forces also said that the case against the Wagner fighters – who were accused of armed insurrection – was now closed, as the rebels had not broken the law.

They can either join the regular army, return home or go to Belarus, President Putin said. He said the fighters were mostly “patriots” who had been led on a criminal adventure.

President Putin said this after an angry speech on Monday night in which he accused the rebel leaders of wanting to “make Russia suffer in a bloody conflict”.

The Wagner militia’s revolt has also created a diplomatic dilemma for Mali, Central African Republic (CAR), Mozambique and Madagascar among others, where the mercenary group’s forces have been crucial in their internal conflicts.

If Wagner stops its operations in Africa, it would certainly hurt the group’s finances.

The United States said in October 2022 that the mercenaries were using natural resources in CAR, Mali and other places to pay for fighting in Ukraine – a claim Russia denied at the time.

| The past catching up

Putin, who has presented himself as the successor to past Russian imperial glory, may end up with the fate of many tsars before him: a military revolt against his own rule, driven by the backlash of a failed war.

“This is a betrayal of our country and our people. This is exactly what happened in 1917 when the country was in World War I and victory was snatched away,” Putin said in a speech on the evening of Friday, 23 June, comparing the revolt to the uprising that destroyed Tsarist Russia during the First World War. “The intrigues and quarrels behind the army’s back have proved to be the biggest disaster: Destruction of the army and the state, loss of vast territories, leading to tragedy and civil war”

The far-right Wagner group has little in common with the left-wing Bolsheviks who seized power in the revolution that overthrew Tsar Nicholas and founded the Soviet Union. II But the background conditions of the uprising that threatened Putin’s regime – especially the discontent caused by a failed war – are nevertheless similar to those that triggered the revolt more than a century ago.

Although the tsar’s enemies were strongly driven by the ideology of revolutionary communism, the revolution could not have taken place without the immense bloodshed of the First World War; the suffering during the war was the spark that ignited the uprising.

Russians, fed up with being thrown into the slaughterhouse of trench warfare for reasons that had little to do with their own lives or interests, finally turned against the tsar and supported the movement that seemed most likely to bring a swift end to the conflict. The war eventually led to massive discontent with tsarist rule and gave impetus to the mix of angry populist movements that ultimately destroyed the regime of Nicholas II at the same time as convincing regular Russians that that they had little to advantage from protecting their monarch.

During this period, Russia was more unstable and had more serious internal problems than many other great powers, so the shock of war resulted in correspondingly greater chaos. But this description could also apply to modern Russia.

Putin’s dictatorship is also characterised by a combination of incompetence, corruption and disregard for the suffering of his own people. Russian society has been rapidly impoverished by the invasion of Ukraine that began in early 2022. While wealthy Russians have fled the country to countries such as Turkey and Dubai, tens of thousands, perhaps many more, have been forced to die on the grim battlefields of war-ravaged eastern Ukraine, including thousands of former prison inmates recruited as fighters for the Wagner Group.

Just as the First World War was started in the interests of monarchs who cared little for the lives of those who fought, the reason for these deaths in Ukraine remains unclear to many Russians, while a resolution to the conflict remains elusive.

Instead of facing the harsh realities of war – such as military failures, sanctions, mobilisation, inflation and mass emigration – most Russians either blindly followed their government or looked the other way. The Kremlin’s reluctance to escalate the war and slow progress in gaining territory have drawn increasing criticism from Russia’s far-right bloggers, who are hugely influential on social media. This will lead to more people doubting and questioning the Russian authorities.

Prigozhin’s rebellion is more than an attack on the Russian army. It is an attack on Putin himself – the worst crime that can be committed in Russia. Putin, speaking to the nation on 24 June about the situation, called it “treason” and “high treason” It must have been hard for Putin to say these words publicly, because they show his personal failure. Putin has tried to avoid responsibility for the failure of the army, the Ukrainian drone attacks inside Russia and the invasion of the Belgorod region by blaming the military.

However, a rebellion on the Russian streets is not just about the war with Ukraine. It is about the entire system over which Putin rules. Prigozhin has long criticised the war, but when tanks move out and head for Moscow, it means Putin is no longer in charge. Even if Prigozhin’s rebellion is stopped soon, it will be too late. For Putin and his system, the damage has already been done.

Prigozhin, who claimed to have at least 25,000 men under his command when he rebelled, took advantage of this unfortunate situation. He had not hidden the impact of the badly fought war in Ukraine on his thinking. The catastrophic loss of life over a small piece of territory in Ukraine last year is eerily similar to the senseless battles and trench warfare of the First World War. In places like Bakhmut, towns were destroyed at the cost of thousands of casualties on all sides. The head of the Wagner Group has accused the Russian military leadership of concealing the true cost of the war with falsified casualty figures and exaggerating the threat that Ukraine and NATO posed to Russia before the war began.

“Huge numbers of our fighters, of our combat comrades, have been killed,” Prigozhin said in an audio message posted to Telegram. “The evil that the military leadership of the country bears must be stopped. They neglect the lives of soldiers. They forget the word ‘justice’ “.

Prigozhin called his revolt a “march of justice” rather than a coup d’état and promised to challenge Russia’s military leadership.

Although details are still vague, some reports suggested that the Wagner chief received concessions in return for the withdrawal of his troops, including a change in the military staff running the war. The mercenary leader has been a vocal critic of the Russian military leadership, particularly Defence Minister Sergei Shoigu, since the beginning of the war. The Russian military offered only limited resistance to his offensive and avoided fighting the Wagner group in Rostov-on-Don.

The Russian government nevertheless treated his uprising as a deadly threat, filed criminal charges against Prigozhin for “inciting an armed insurrection” and had military and police forces stationed throughout Moscow in preparation for the arrival of Wagner’s troops. The charges, brought by Russia’s Federal Security Service (FSB), can be punished with 12 to 20 years in prison. “Prigozhin’s statements and actions amount to calls for the start of an armed civil war on Russian territory and are a ‘betrayal’ of Russian soldiers fighting pro-fascist Ukrainian forces,” the FSB said in a statement circulated by state agencies. And Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov said President Putin was aware of the “developing situation” around Prigozhin and that “all necessary measures” would be taken.

If he had succeeded in taking power, Prigozhin would not have created a more liberal or progressive Russia. Given the terrible track record of his organisation, the opposite is more likely. Nor is there any evidence that he would have ended the war in Ukraine if he had had the chance.

Nevertheless, the leader of the Wagner Group posed the most serious challenge to Putin’s rule since he took power more than two decades ago. Prigozhin owes this chance, which may not be his last, to a failed war and its impact on an autocratic regime. “The war put Russian society in a state of extreme stress,” Vladimir Lenin noted with delight a century ago, reflecting on the impact of the First World War on his tsarist opponents. “The revolution drew its first breath from the war”.

| Implications for EU and US policy

Developments within Russia will, of course, be determined by Russians. However, the West is in a position to influence the opinions of elites and the public about what a post-Putin Russia might look like, which could both increase pressure on the regime and help shape the opinions and aspirations of those who come after it.

For this to happen, however, Russia would have to end the war in Ukraine, open up political space and engage constructively with the West and Ukraine again.

But the Kremlin seems to find the idea that Russia will inevitably come into conflict with the West useful in justifying its isolation from Europe. Putin has even tried to create a “Eurasian” identity for Russia, contrasting the increasing liberalism of the West with Russia’s traditional conservatism, for example on LGBTQ+ issues. The Kremlin’s rhetoric and propaganda has changed perceptions; as a Levada poll from 2021 found, fewer Russians consider Russia to be a European country than they did in 2019 or 2008.

However, Russia is a European country in that it has historically oriented itself towards the West and been a major player in European affairs. The pre-Soviet tsars were strongly oriented towards Europe, and Russia’s geopolitical, economic and cultural centre of gravity was also in Europe during the Soviet era, and even at the beginning of Putin’s rule.

In other words, Putin’s efforts to create a Eurasian identity, naturally in opposition to Europe, are on weak footing – even if his narrative has been strengthened by current tensions with the West.

It could be effective to reject the notion that the West and Russia are inevitably in conflict and to emphasise that Putin is the one isolating Russia and preventing it from having a European – and thus more prosperous – future.

Bringing such a message into Russian society and overcoming state propaganda is difficult, but not impossible. Messages and narratives can and will find a way to reach Russian elites and the well-connected public. Since the partial mobilisation in September, the broader Russian public is also looking for more reliable information about the war in Ukraine

| A liberal democratic Russia?

There are good reasons to doubt the possibility of a liberal democratic Russia that is not hostile to the West. Putin is essentially a mirrored image of the Russian public, and he is popular not least because hardline nationalism is popular in Russia. Democracy has been badly battered by the political chaos and economic collapse of the 1990s, which led to the development of patronage capitalism rather than a strong and dynamic market economy. Much of the Russian public has also been subjected to anti-Western propaganda for most of the last century. Therefore, any new leader or regime might resort to a hard line nationalist stance to gain public support.

Moreover, Russia couldn’t live on as a country without autocratic rule, because its multi-ethnic polity, built through imperial conquest, could fall apart without Moscow’s uncompromising authority. Even if the Russian leadership strives for a democratic future, the country could still fall apart. Russia could revert to the lawless chaos of the 1990s, when mafia groups, armed oligarchs and separatist movements exploited the weakened state.

This is undoubtedly a cause for concern, but today’s Russia is very different. In the early 1990s, it confronted a tough transition from a command economy to a free market economy, and the resulting economic collapse significantly weakened Russian state capacity.

In contrast, a departure from Putin could bring enormous economic benefits. A new, more liberal regime in Moscow would not face the same difficulties as in the 1990s. Moreover, while there is a real potential for a new wave of secessionist movements, this is offset by broader Russian patriotism, greater identity and stronger ties to the state.

The chances of Russia taking a liberal, democratic, pro-Western path are slim – even if the public had the opportunity to do so – but it is not impossible either. Although creating a multi-ethnic representative democracy in Russia, a country with an almost uninterrupted autocratic history, seems unrealistic, similar things were said about Germany after World War II. Europe, a continent that has been at war for most of its history, has united in a federal union. Even if Russian NATO or EU membership seems highly unlikely at the moment, the West should at least be open to this possibility, however small or distant.

Ultimately, Russia’s future will be decided by the Russians, not by the West. However, it costs nothing to let the Russians know that the West will welcome them if they seek democracy. Such an approach could affect how Russians feel about the Putin regime and their future. As much as the rhetoric of retaliation may feel justified, as it did towards Germany after World War I and II, the wiser path focuses on rehabilitation and integration.

The West offered this not out of generosity but because of geopolitical competition with the Soviet Union. Similarly, encouraging and prodding a post-Putin Russia to abandon its anti-Western attitudes and vicious revisionist approach to the international order would have a big geopolitical impact on US-China relations, European security and the liberal world order in general.

There are two striking examples here: the Soviet Union did not collapse when Ronald Reagan or the West had an iron fist, but when they had an outstretched arm. The Green Movement in Iran did not erupt when the United States threatened to bomb the country, but after the newly sworn-in President Barack Obama addressed the Iranian people in a New Year’s message offering a “new beginning” that became impossible when Mahmoud Ahmadinejad was re-elected president three months later, under highly dubious circumstances.

Correlation does not equal causation, but there is never just one factor that triggers a revolution. Providing a degree of hope for a better future, a more liberal future within even a small section of society can have the most powerful effect.