Outgoing prime minister, Mariano Rajoy (right), congratulating incoming prime minister, Pedro Sánchez (left), upon losing the no confidence vote on 1 June 2018 © Pool Moncloa/Diego Crespo

Spain has long been a place of legends and proverbs, not all of them especially encouraging. “Thou shalt make castels thane in Spayne, and dreme of joye, all but in vayne’” wrote Jean de Meun and Guillaume de Lorris in their two-handed 13th century story in verse, Roman de la Rose, “And thee deliten of right nought, / While thou so slombrest in that thought” At least, that is the wording in Geoffrey Chaucer’s 15th century translation. The original poem goes as follows: “Lors feras chastiaus en Espaigne /E avras joie de neient /Tant con tu iras foleiant /En la pensee delitable /Ou il n’a que mençonge e fable.” Mediaeval French was slightly different from what you’ll hear today on the Paris Metro or read in Le Figaro or Libération (or in La Libre Belgique, for that matter). It meant having unrealisable ambitions and dreams, hopeless hopes that could never be fulfilled. By the 15th century, the reference to “castles in Spain”, whilst remaining in currency in France, had long been replaced in everyday English by the expression “castles in the air”, which means the same thing. Where the expression comes from is a matter of some debate, although most people think it dates back to the time when much of the Iberian Peninsula was under the control of the Moors, who invaded in 711 and remained in charge until 1492. Back then, any castles a Christian leader (such as a French knight, perhaps?) might build in Moorish territory were quickly knocked down, which may be why it was considered an impossible goal. Running this difficult and multi-faceted country has been proving difficult for Spain’s Prime Minister[1], Pedro Sánchez, but not yet impossible. His difficulties are far from over, however.

Actually trying to run Spain has long been a difficult job. After all, it had a dreadful civil war that ran from 1936 to 1939 and completely divided Spanish society. It had been caused by the failure of democracy and an uprising by right-wing generals. Altogether, some 500,000 people lost their lives in the conflict, of whom about 200,000 died as the result of systematic killings, mob violence, torture, or other brutalities. It was a ghastly time for the country with both sides guilty of committing atrocities and it was won, eventually, by Frederico Franco’s ultra-nationalists, aided by Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy.

The German airforce attacked known Republican positions and completely obliterated the Basque town of Guernica, which shocked the world and inspired Pablo Picasso’s famous and brilliant painting. Such an attack is reported in detail by the Anglo-French writer, Robert Payne. He was visiting the battlefield with the Republican Spanish poet, Vicente Campos. After hiding among vines, Campos was exuberantly celebrating the Germans’ poor marksmanship, having missed all their visible targets, when Payne noticed they’d had at least some success. “Half an hour later, when we were on our way to Mora de Ebro, I realised that I was stuck to the bench in the back of the truck,” he wrote in his book, Eyewitness. “A bomb splinter had caught me in the buttock and the blood acted as a glue. There was also a trickle of blood from my right ear, and I was to learn later that the explosion of the bomb had cracked the eardrum.” He remained deaf in that ear for the rest of his life. When he and his little group reached Mora de Ebro, they found that the village had been turned to rubble with not a single house left standing. Even today, many Catalans would like their particular part of Spain to be independent. Flying Catalan flags is, strictly speaking, illegal (a law ‘more honoured in the breach than the observance’[2]) but they are all over the place in Barcelona, or they were the last time I was there.

The separatists even had a stall selling Catalan t-shirts, mugs and other such items at the annual (and wonderful) festival of books and flowers. Given that linking of the two things should make the verse-book ‘Romance of the Rose’ popular in Catalonia.

It doesn’t seem to have swayed Sánchez’s opinion, apparently happily condemning the promotors of a referendum on independence to 100 years in prison.

He does not seem to have worked out yet that you cannot imprison an idea, even if you can scare people into denying that they support it.

The total refusal to negotiate with the separatists was the policy of previous prime minister Mariano Rajoy, but Sánchez has been blindly following the same path. In the UK, when nationalist and separatist ideas started to gain traction in Scotland and Wales, the UK government of the time reached an accommodation with the leaders of the states that make up the UK which may or may not last. Under it, both were granted a degree of self-rule, which the overall UK government hoped would suffice. In Scotland’s case, it may not survive another referendum, which is why the overall government is refusing to allow one. The last time one was held, the argument for remaining part of the UK was that it was the only way Scotland could stay in the EU, which it needs for its exports (whisky is popular everywhere). That, of course, no longer applies; an independent Scotland, where a considerable majority voted against Brexit (in the referendum to decide if the UK would leave the EU), would presumably apply to re-join. Things may be changing, however: Sánchez told the Spanish parliament in May that his government was considering possible pardons for the separatist politicians “for the benefit of co-existence among Spaniards”.

The separatists were sentenced in October 2019 for sedition, misuse of public funds and disobedience but the government has the power to overturn that decision if it wishes. Furthermore, in the touchy partnership of El Partido Socialista Obrero Español (PSOE), headed by Sánchez, of course, with the similarly left-wing Podemos, Sánchez relies upon the support of the Republican Left of Catalonia. Sánchez knows, however, that a move to pardon the separatists would be opposed by the moderately right-wing Partido Popular and their supporters.

WE DON’T TALK ANYMORE

Sánchez sometimes seems to find negotiation difficult. He is sharing power with fairly like-minded politicians, after all, but they disagree on several things. The website of International Socialist Review explains the problem of having two main parties backed by smaller groups, not only in terms of negotiations (or the lack of them) but in the wider terms of governance and policy: “The Socialist Party introduced neoliberalism into Spain.

It is responsible for much of the devastation caused to ordinary Spaniards by the Great Recession. The Popular Party matched the Socialist Party in wreaking economic mayhem. It negotiated the austerity agreement imposed on the Spanish state by Europe’s ‘troika’ (the European Commission, the European Central Bank, and the International Monetary Fund). Both parties are profoundly tainted by corruption.” The website seems to argue that the Socialist Workers Party is as much to blame as its centre-right rival for the chaos of Spain’s economy. “The PSOE and the PP—like their counterparts in Portugal and Greece—treated Spain’s public patrimony as the occasion to hold a gigantic garage sale. Together they relentlessly privatized state enterprises in the energy, transportation, and communication sectors. Sadly, the traditional left parties proved incapable of organizing resistance to the neoliberal onslaught. In a number of cases, they simply acquiesced to both neoliberalism and austerity.” It’s not a great end-of-term report, but then Spain only returned to democracy in 1978. Furthermore, the PSOE has suffered as other social democratic parties in Europe have from dwindling support. They fought through the post-war years to build a more equal society through modernisation but now it has been delivered, more or less, many voters are looking to see if they can find something new and more interesting. As a result, PSOE’s share of the vote has dwindled, down to just 90 seats out of 350 in 2015 and then to 85 in 2016.

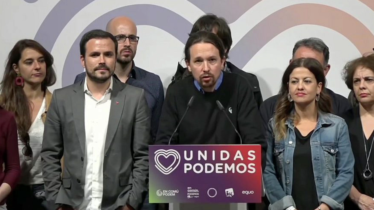

Much of the problem seems to stem from the fact that Sánchez simply doesn’t seem to talk much to other political leaders. That is a serious handicap in a coalition government. However, they did negotiate in November 2019 after a second election, only months after another general election had brought no clear winner. “As I said on election night after hearing the results, what was a historical opportunity in April has become a historical necessity,” said the Unidas Podemos leader, who had refused high office after the indecisive first vote. “I’m pleased to announce today, together with Pedro Sánchez, that we have reached a preliminary agreement to create a progressive coalition government that combines the experience of the PSOE with the courage of Unidas Podemos.” It was an almost desperate bid, in reality, to halt the growth of the far-right party, Vox, which had gained the most votes since the earlier election, although nowhere near enough to get into government.

As the Spanish newspaper El País reported it at the time: ““The agreement wasn’t possible,” said Sánchez, in reference to the parties’ failure to do a deal after the April polls. “We are aware of the disappointment. It will be a progressive government whatever the case. A progressive government made up of progressive forces that are going to work for progress. There is no room for hatred between Spaniards.”” That last comment was almost certainly a reference to Vox, whose number of MPs soared from 24 to 52, making it the third biggest party in the Cortes Generales, as the parliament is called. Such was the fear among the journalists covering the event of the need for a third election that when Sánchez embraced the leader of Podemos, Pablo Iglesias, there was an audible sigh of relief.

LOOK RIGHT

Politics is a dangerous profession in Spain. Iglesias has received death threats from the far right. At any political rally held there, it’s easy to spot the Vox supporters (or at least the male ones): they tend to have very short hair or shaved heads and quite a lot of tattoos, much the same as far-right supporters (and football hooligans) in other countries.

They have been much in evidence in the lead up to regional elections that saw a right-wing member of Partido Popular win Madrid. Her campaign platform was against lock-downs and restrictions on movement to curb the pandemic; Isabel Díaz Ayuso says her campaign slogan is “freedom”. One has to hope that the SARS-CoV-2 virus doesn’t adopt the slogan, too.

The country does not seem to be able to flatten the curve of infections, despite efforts to curb the spread by barring the population from all social interaction. The confirmed number of cases of the coronavirus disease in Spain reached more than 3.5 million as of May 6, 2021. The virus has spread to every region in Spain, with Madrid suffering the highest number of cases: more than 600,000 people. Ayuso’s policy of loosening the restrictions seems to have played well with the voters but we have yet to see the results in health terms. Ayuso has said she will not go into coalition with Vox, which still has a toxic reputation for a large part of the electorate, but there are many others who still look favourably on the far right. When Catalonia illegally issued its ‘declaration of independence’, Vox’s membership rose by 20% in just 40 days.

Vox came in for criticism during the campaign for claiming that underage immigrant are ‘a burden on regional finances’, but a poll of PP supporters found 78% in favour of their party forming a coalition with Vox. Vox would clearly back some of her other policies, such as lowering taxes, encouraging bullfights and having fewer controls to combat the pandemic because they endanger the economy. Vox is an authoritarian party, opposed to what it calls “radical left-wing feminism”, favouring traditional gender rôles for people, with men at the top, of course. It goes without saying, I imagine, that its economic viewpoint is ‘neoliberal’.

It’s a problem for Pedro Sánchez. He is, by nature, an internationalist. Unlike the supporters of Franco (and they haven’t all gone away) he believes in countries cooperating with one another to tackle problems that – in today’s connected world – tend to themselves to be international. Even Franco’s government, of course, was happy to cooperate with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy. In a German symposium held every year at the London School of Economics, Sánchez spoke to the assembled German students about the future of a post-Covid Europe, relations between Spain and the EU and about the European Union’s relationship with the UK after Brexit. He called for “multilateralism and international solidarity” to tackle the crisis. “I continue to trust in this pandemic leading to a fundamental leap towards international cooperation that lasts for generations,” he told his audience. He furthermore declared that Europe should continue to lead the response to the major challenges of our time, and he underlined what he called the “decisive” rôle of the EU in fighting the pandemic and in mitigating its socio-economic impact. He used his speech earlier this year to call on the EU to “step up” its collaboration to guarantee affordable and fair access to the available vaccines. “No-one will be safe until we are all safe,” he said. “This not only means ensuring that everyone is vaccinated in Spain, but also in the rest of the world.”

He would not be impressed by the debate in the European Parliament over a proposal to waive the patent on the vaccines to speed up their use, especially in the Developing World. The left supported the idea, while the centre and right expressed fear that by denying pharmaceutical companies the vast profits a successful vaccine could provide would rather stifle innovation. MEPs on both sides criticised the US and the UK for hoarding too many doses at a time when poorer countries have little or no access to jabs. The only organisation to have tried to overcome the difficulties has been the EU, which has exported roughly half of its production to countries in need. However, while India and South Africa proposed an official patent waiver to the World Trade Organisation (WTO), a cautious (some might argue ‘reactionary’) EU put forward a counter proposal in response to pressure from the lobbyists of large pharmaceutical companies (sometimes referred to, somewhat insultingly, as ‘Big Pharma’), who want to hang on to the patents resulting from the hard work of their researchers. Surprisingly, the US threw its weight behind the waiver idea (although at the time of writing it had yet to implement it), but the EU, Japan, the UK and Switzerland blocked its adoption. The left argues that in this instance, profits are being shown to be more important than people.

The EU’s proposal, quoted in The Times of India, is to “facilitate the use of compulsory licensing within the trade-related aspects of intellectual property rights (TRIPS). The agreement already provides this flexibility, which is a legitimate tool during the pandemic that can be used swiftly where needed.

” Although it hasn’t, so far. It sounds to many like a rather feeble cop-out. Incidentally, Bill Gates also spoke out against the waiver, despite his work for the under-privileged around the world. The pandemic is still raging in a number of poor countries such as India, Brazil, Iran and Nepal but the better-off countries still seem reluctant to share. “It did not have to be this way,” says the professional periodical for doctors and surgeons, the British Medical Journal (BMJ), which is clearly aware of the UK’s part in blocking the plan. “We have multiple safe, highly efficacious vaccines that we should be deploying worldwide to end the pandemic.

And yet only 0.3% of total doses have gone to low-income countries, a grotesque inequity that Winnie Byanyima, executive director of UNAIDS, calls ‘vaccine apartheid’.”

The disparity in access to Covid-19 vaccines between rich and low-income countries – the very thing Sánchez opposes – has become impossible to ignore. According to data from UNICEF, 86% of all doses given worldwide up to the end of March were administered to those in high- and upper-middle-income countries, while just 1% of jabs have been given to those in the world’s poorest places. In the face of well-funded lobbyists, there’s not a lot that Sánchez can do about it, however disturbing it may seem. Other voices have also been raised without affecting the attitudes of Big Pharma, such as Dutch member of the European Parliament, Guy Verhofstadt.

“It is for the upcoming authorisations of vaccines from, for example, Johnson & Johnson and CureVac,” he wrote, “that the European Medicines Agency must follow a fast-track procedure, putting aside the question of liabilities towards third parties. And in the longer term, a real health union must be established with a real budget so that we can match the US in supporting the development and production of new medicines and treatments by the pharmaceutical industry. Part of this union must also be a dedicated agency responsible for the European-wide acquisition of medicines to avoid the errors made during this pandemic. And finally, also, the question of patent rights needs to be openly discussed and addressed.” He’d get no argument from Spain’s leader. Sánchez has been a long-term advocate of equality, which seems to be in even shorter supply than a Covid vaccine in a poor country. He has promised that by the end of August, 70% of the Spanish people will have been vaccinated.

Catalan News reported this public commitment: “In a press conference held on Tuesday, he pledged to reach some vaccine rollout landmarks including having fully inoculated 5 million Spaniards by the week beginning on May 3, 10 million by the first week of June, 15 million by the week beginning on June 14, 25 million by the week beginning on July 19, and 33 million residents by the end of August.” It’s a bold move, because failure to reach the targets would be seriously damaging to his prospects of re-election.

IS SUPPORT FLAGGING?

The Covid-19 pandemic, however, is not the only problem Sánchez has. According to the State of the Left website, he faces a number of challenges. Firstly, says the article, he must “facilitate the regeneration of the party internally and externally”. His fellow-members are a disputatious lot, it seems. Spain has also developed what the media call a ‘war of the flags’, with the Spanish flag being looked at as a symbol of the far right, something of which Sánchez firmly disapproves. He told the media that the flag “is a fabric that symbolises a nation woven by 47-million threads, one that represents everyone, with the will to live together, create a project for a common country, and that no-one has the right to use it against others”.

In fact, it is a reflection of a trend that has been seen across much of Europe, with far-right parties conflating neo-nationalism with national pride and a developing hatred for others, especially those of different faith or colour. It’s a form of tribalism that our mammoth-hunting ancestors would have appreciated, right before they struck you on the head with a stone axe. “The poison of hate is the most damaging,” said Sánchez. “Let us say no to the poison of hate, no to verbal and physical violence, no to insults and provocations. Our parents did not sacrifice themselves for this.”

Flag-waving nationalists have become surprisingly common across much of Europe and the world and flags are very emotive. Those campaigning in favour of Brexit in the UK were inclined to carry the Union flag (often incorrectly called the Union Jack and sometimes unwittingly held upside down) to demonstrate their belief in separatism and national isolation. The pro-Trump rioters who invaded the Capitol in Washington were not only carrying guns but also brandishing Confederate flags, which is against the law. NBC News reported that: “The sale or display of Confederate flags, swastikas and other ‘symbols of hate’ on state property is banned in New York under a law signed by Gov. Andrew Cuomo,” despite concerns that it may violate free speech protection under the U.S. Constitution. “This country faces a pervasive, growing attitude of intolerance and hate — what I have referred to in the body politic as an American cancer,” Cuomo said in his bill-signing memo. The Confederate flag has come to represent not so much the states that broke away in 1861 as simple white supremacy and a belief in segregation.

Meanwhile, relations with Morocco have worsened. The problem has its roots deep in Spain’s colonial past. Five small areas, on or very near the coast of Morocco, remain in Spanish hands. They are Alhucemas, Ceuta, the Chafarinas Islands, Melilla and Peñón de Vélez de la Gomera, totalling altogether almost 32 square kilometres. Ceuta is administered as part of Cádiz province, the rest as part of Málaga province. The current war of words is to do with the conflict in the Western Sahara, which began with an insurgency against Spanish colonial rule by the Polisario Front. Once Spain withdrew from what had been called the Spanish Sahara, the Polisario Front began what turned into a 16-year independence war against Mauritania and Morocco, aimed at establishing the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR). More recently it’s been called an intifada against Morocco, with Algeria and Libya on the side of the Polisario Front.

The current row concerns Spain’s decision to admit the rebel leader, Brahim Ghali, for medical treatment without informing the Moroccan government first.

Morocco promptly said it would open its borders to let some 10,000 migrants enter the enclave of Ceuta. Most migrants who make the crossing are rounded up and returned to Morocco, but Spanish law forbids the deportation of minors, so Spain suddenly found itself responsible for a large number of children.

Sánchez described Morocco’s action as unacceptable while Morocco said that by admitting Ghali for treatment, Spain violated ‘good neighbourliness’. Ghali has been hospitalised, suffering from COVID-19. Morocco has withdrawn its ambassador and has threatened to sever diplomatic links with Spain if Ghali is allowed to leave without facing trial.

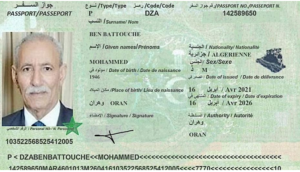

Ghali, along with his lieutenants, stands accused of genocide, murder, terrorism, torture and the “disappearances” of rivals. Morocco regards the Western Sahara as part of its own territory. Sánchez reminded Rabat that Spain is Morocco’s best friend inside the EU. It has served a court summons on Ghali, too, but at the time of writing it is unclear whether or not he holds an Algerian diplomatic passport, which would rule out the chance of a trial. Sánchez said that admitting Ghali for medical treatment had been a “humanitarian gesture”, although it looks like being one that could plague him for some time.

WALKING INTO A GREENER FUTURE

Sánchez seems determined to make Spain a more ambulatory country. Back in May, he announced his plans for reform over the next thirty years. His “España 2050” plan is certainly radical, which means it may be hard to deliver.

On the issue of employment, he admitted that full time contracts may no longer be an option and that Spain’s focus will be on retraining its workforce. It’s an ambitious scheme: he foresees having to retrain some 90% of the population, after which employment will involve a simplified work contract. It could mean the end of ‘jobs for life’. Sánchez also promised to overhaul the taxation system by increasing taxes and introducing a tax on wealth, inheritance and goods. He wants to modernise education and increase the numbers of students going on to higher education from an already impressive 70% to 93%. He also plans to incentivise women to have more children – like Italy, Spain has a falling birth rate – with financial aid for mothers. He has said he wants to reduce Spain’s reliance on cars and air travel to reduce pollution, putting the country’s focus on rail travel. That means scrapping short haul domestic flights that would take less than 2 hours 30 minutes by train. If people must have personal transport, he wants it to be electric. Otherwise, he wants to see more people walking.

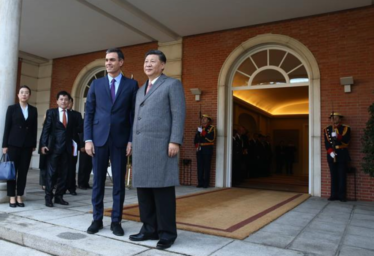

Altogether, the plan has not been very well received. Nor has his telephone conversation with China’s President, Xi Jinping, in which they discussed the possibilities for China to co-invest in projects being part-funded with EU recovery funds. Brussels, like Washington, is wary of China gaining increased power and influence in Europe, especially where it involves funding crucial infrastructure projects. But the Spanish government said in a statement that Sánchez had told President Xi that he was sure they could reach some sort of ‘common ground’, with Spain playing an important rôle in improving Sino-European relations. Spain is anticipating receiving around €140-billion in pandemic recovery funds from the EU in the near future and Sánchez reminded Xi of the huge investment opportunities in “the green transition, electric mobility, circular economy and digitalisation”. Overall, it would mean fewer cars, higher taxes on more things, less job security and – the sweetener – shorter working days. Some have dismissed the whole scheme as unrealistic; ‘castles in Spain’, you might say.

Sánchez has been energetic in his search for an acceptable compromise with the separatists of Catalonia. In a speech during a ceremony in Barcelona in June of this year, he called for the recovery of lost coexistence. “Let us commit ourselves to harmony and reunion as weapons of progress,” he said, “and let us get to work.” The ceremony was to present a medal commemorating the 250th anniversary of Foment del Treball to the publisher and president of the Godó Group, Javier Godó.

Foment del Treball is a federation that has represented entrepreneurs and Catalan industry since its foundation in 1771. In front of a Catalan audience, Sánchez appealed to “every woman and every man in our society, whatever their profession and condition; wherever they live” to have courage and what he called a ‘sense of exemplariness’. He asked his audience to advance the search for “a new ‘us’”, as he put it.

“Let’s exchange threats for proposals, wherever they come from,” he said. “And let us not look for justifications or revenge, but for solutions: with pragmatism, with honesty and with common sense,” adding that in his view “this new ‘we’ will be our greatest success as a society.”

Sánchez also had a message for the Catalan business forum, urging them to take part in the ‘transformation programme’ set out in his ‘Recovery, Transformation and Resilience Plan’. “You are indispensable,” he told them. “Catalonia is essential; we need the best version of Catalonia to lead, as it has always done, the economic and social modernisation of Spain.” He reminded them that May saw a fall in unemployment of 130,000 people and that job creation has reached the same level as before the pandemic, even before the first EU funds arrive in July. No-one could accuse Pedro Sánchez of a lack of ambition. He has many ideas to bring Spain up to date and make it greener and more pleasant, even if not all of them may prove workable. In one recent Tweet, Sánchez said: “Becoming a greener and more sustainable country is one of our aims. We are working on this, in legislating to build a society that cares for its environment, that cares about the present and the future, that is committed to a more ecological and fair system.” Castles in Spain? Well, possibly. But you cannot blame a man for dreaming. And his “dreme of joye,” may not, after all. Be “but in vayne”.