Given its location, an outcrop at the tip of the Iberian Peninsula, just where the Mediterranean meets the Atlantic Ocean, Gibraltar was always certain to be strategically important. In fact, its importance and its significance to national pride in Britain far outweigh its modest size. It is just 5 kilometres from north to south and roughly 1.2 kilometres across at its widest point. Its most famous residents are a tribe of Barbary macaques, the only wild monkeys to live in Europe. They may have been introduced by the Moors who lived there from 700 until nearly 1500, and they were presumably brought there as pets, although there are also claims that they only appeared in the 17th or 18th centuries. Recent DNA analysis shows them to be of Moroccan and Algerian origin genetically, proving that they are not, as some have claimed, remnants of a population that existed in Europe before the last ice age. They’re not apes, either: despite the lack of a visible tail (their tails are almost vestigial, or at least very small) they are, in fact, monkeys. It’s stated, although it remains unproven, that it was the monkeys that saved the territory from a combined attack by Spain and France during the “Great Siege”, that lasted from 1779 to 1783. It’s said the monkeys heard the attackers approaching and kicked up such a racket that they woke up the British forces (why were they asleep during a siege?), causing the attack to be abandoned.

As a result, it’s said that Gibraltar will stay British as long as the macaques remain there, snatching sandwiches, sweets and other goodies from tourists too busy saying “Oh! Aren’t they sweet?” to notice their concerted efforts at petty larceny, a pastime at which they are said to excel, especially with regard to food.

Britain’s wartime leader, Sir Winston Churchill, considered the macaques so vital to British interests in terms of self-confidence and prestige that he ordered the then colonial secretary to find ways to increase their numbers and maintain them thereafter. The order was duly obeyed, the macaques multiplied and they now number just over 300, divided into seven separate troops, which do not have to suffer, shivering through the winter in Morocco and Algeria when snow coats the Middle Atlas mountains, but live as much-loved assets to the population and to the summer visitors, often climbing on them. As to their diet, quite apart from the tourists’ sandwiches, often purloined, there is an ample supply of wild food for the discerning monkey. According to the Discover Wildlife website, “Their varied plant diet ranges from olive leaves and fruits to the roots of introduced Bermuda buttercups, and this is supplemented with live prey, such as small lizards and numerous invertebrates.”

But while the combined forces of pre-revolutionary France and the Spain of King Carlos III failed to prise Gibraltar from Britannia’s grasp, it seems as if the jingoistic (if seemingly ill-informed) patriotism of the Brexit campaigners may have driven the territory partially into the arms of Madrid and its (and until lately Britain’s) trading partners in the European Union. I’m sure that obliging the Gibraltarians to seek comfort within the Schengen group was the very last thing the enthusiasts for Britain leaving the EU had in mind. However, unintended consequences seem to have come into play, with Britain’s notoriously right-wing and largely anti-European press having failed to inform their readers of this possibility. There again, Gibraltar is quite a long way away, so perhaps they didn’t really care much, either. As the great Scottish poet Robert Burns put it in his poem ‘To a Mouse’, “The best laid schemes o’ mice an’ men / Gang aft a-gley.” In other words, however hard you plan, things can still go wrong in a way you hadn’t anticipated. If it all happens, it will mean that Spanish citizens can enter and leave Gibraltar without stopping at the border, as will citizens of all the other Schengen member states, but anyone from the UK will still have to carry a passport, as they do now. This is unlikely to please Britain’s neo-nationalists (or its bombastic, bellowing mainstream media). So far, then, in terms of patriotic fervour for Gibraltar, the score is Barbary macaques 1, Brexiteers 0. It was the Arabs who first named it, at least on the public record. After all, it has been inhabited consistently for almost 3,000 years and was at one time home to a group of Neanderthals who lived there more than 50,000 years ago. Who knows what they called it, other than by whatever their word was for ‘home’? We don’t know what the Phoenicians called it, either, during their stay. They arrived there in around 950 BC. The Carthaginians visited it, too, as did the Romans, building shrines to Hercules on the famous Rock of Gibraltar. The Romans did give it a name: Mons Calpe, which means Hollow Mountain. The Arabs, though, called the place Jabal Ṭāriq, which means the Mount of Tarik, in honour of Ṭāriq ibn Ziyād, who captured Gibraltar for them in 711 CE. He turned it into a fortress and its successive rulers have followed suit. It was the name Jabal Ṭāriq, of course, that evolved into Gibraltar.

The Arabs lost the place to the Crown of Castile in 1309, since when it has remained Christian, except for a break between 1333 and 1462, when the Moors seized it and made it Muslim again. Spain then took it back, but during the War of Spanish Succession it was captured by an Anglo-Dutch fleet in the name of one of the contenders for the Spanish throne, the Habsburg Charles VI of Austria. When the war ended, Spain ceded Gibraltar to Britain in 1713 under the Treaty of Utrecht, although, as the incident with the apes proved, Madrid wasn’t entirely happy about parting with it, hoping to take it back later. In that sense, nothing much has changed; Spain would still like to regain the territory. It has been symbolic of British naval strength since the 18th century, however, and it has remained the guardian of the Straits of Gibraltar.

Its strategic importance was especially noticeable during the Second World War, when control of the Mediterranean was vital to all sides. It came under sustained and repeated attack from Germany, Italy and even from Vichy France which staged a number of bombing raids, although relatively little damage was inflicted. A British naval trawler, the HMT Lady Shirley, was sunk by a torpedo, however, with the loss of all hands, but not before she herself had sunk U-111, capturing her 44 crew.

Nazi Germany tried to get the Spanish dictator, Francisco Franco, to help it by occupying Gibraltar but, somewhat surprisingly, he declined, although he did renew his claim to the territory when the war was over. However, he closed his country’s border with Gibraltar from 1969 until 1985, during which time there was virtually no communication. Britain, along with the Gibraltarians themselves, stuck to the claim of self-determination, rejecting Spain’s ambitions. Negotiations about the place between Madrid and London have continued, on and off, ever since. Who would ever have imagined that the most eagerly flag-waving English nationalists would have chosen, without realising it, to jeopardise its status as a British territory?

It remains British, however, as UK Foreign Secretary Dominic Raab assured the media. “We remain steadfast in our support for Gibraltar,” he said at a press conference after agreement was reached, “and its sovereignty is safeguarded.” The deal is a temporary one, just for the next four years, and its details remain shrouded in mystery. The nub of it is, though, that the border between Gibraltar and Spain remains open, as it is now. Chief Minister Fabian Picardo assured citizens that Gibraltar’s “red lines” remain unbroken but that its relations with its nearest neighbour were being “reset”. “There are no aspects of the framework that has been agreed that in any way transgress Gibraltar’s positions on sovereignty, jurisdiction or control,” he said.

SMALL PLACE, BIG PROBLEM

With a total area of around 6.72 kilometres, which makes it 15 times the size of Vatican City, 3.4 times the size of Monaco but less than 24% the size of Liechtenstein, it’s pretty small, by any standards. Its population is also an unremarkable 33,686 at last count, making it just 0.00043% of the world population. It is also deeply undercut by about 16 kilometres of tunnels, mainly dug for defensive purposes over the years. In 1967, Gibraltarians voted overwhelmingly to remain British, and in 2002 they voted not to share sovereignty with Spain.

However, in the 2016 referendum on Britain’s continued membership of the European Union, they voted by 95.91% for Britain to remain in the EU. At present, some 15,000 European – mainly Spanish – citizens commute every day to Gibraltar for work and even if no deal is worked out between Madrid and London, provisions were in place to allow those who had registered their situation before 1 January 2021 to cross, using a document being provided especially for them (where none was needed previously). Negotiations on how to police the border were continuing even after the UK’s EU membership ended, which was essential because the supposed ‘trade deal’ agreed at the last minute made no mention of Gibraltar, which is classed as a ‘British Overseas Territory’. Picardo assured Spanish broadcaster TVE that both sides were working hard to make sure workers remain able to cross easily, with membership of the Schengen area still on the table for Gibraltar, but he warned that “the clock is ticking”. It looks as if travellers from outside the Schengen area wanting to cross the border will need to carry passports to get from Spain to Gibraltar or vice versa.

Gibraltar also depends on tourism, attracting some ten million visitors every year. Their spending accounts for about a quarter of Gibraltar’s economy. Gibraltar will now be regarded as being within the Schengen area, its many British tourists will have to show their passports (as they have done for years), while travellers from within the Schengen countries will not. One assumes this is not the outcome the Brexit supporters would welcome.

“We do not have much time, and the chaotic scenes from the UK must remind us that we need to keep working to reach a deal on Gibraltar,” warned Arancha González Laya, the Spanish foreign minister, just days before the UK’s ‘transition period’ with the EU ended.

As Picardo said at a press conference: “This is a moment where we have the choice to make for our people, of whether we ensure that none of us loses at this table even if none of us wins, or we ensure that all of us wins to ensure that none of us loses. It’s that clear. I’m optimistic that we can get there.” And they did, sort of.

There was a real fear that a failure to find a deal would have turned Gibraltar into a giant truck park, much as it has done with Britain’s south-east county of Kent and other parts of Britain that have major ports.

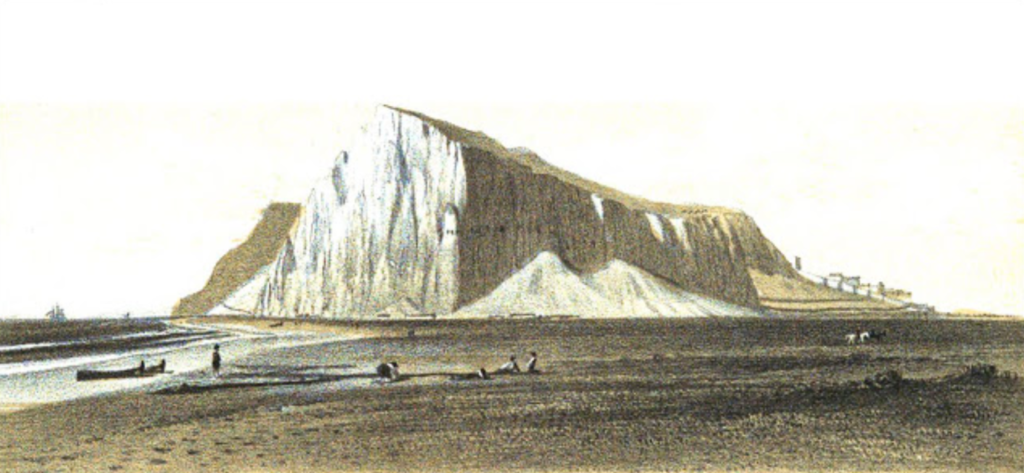

It’s unclear from some government statements if ministers were even aware of the continuing chaos. In one Downing Street briefing, Secretary of State for Transport Grant Shapps assured viewers that the numbers of trucks queuing on the approach to Dover had been reduced from 500 to 130, while a news report later that same evening gave the actual number as “around 1,500”. Shapps clearly hadn’t got anyone to count them. To end up as a truck park would have been unfortunate after the place’s formidable past. The Rock of Gibraltar, for which it is famous, is a promontory rising to a ridge more than 400 metres high. It was formed during the Jurassic era, when the Atlantic Ocean was much narrower and still widening. It is made up mostly of the shells of dead marine creatures, mainly terebratulæ, living at the time in warm, shallow seas. The terebratula is described as having had an elongated biconvex shell, to have been vaguely egg-shaped but small with a “large ventral umbo (the raised pimple in the centre) with pedicle (or stalk) opening, curved hinge line, anterior margin of both the valves with two folds, ornamented with fine concentric growth lines”. So you’ll know one if you ever come across it, although that seems unlikely. They died out in the late Mesozoic era. The shells collected on the sea floor when the animals died and gathered into a pile that turned gradually into limestone. This in turn was lifted up by pressure between the African plate and the European plate coming together, the Rock itself being the highly eroded part of an overturned crustal fold. In other words, it is effectively upside down, with older rock lying above younger, rather as you might get if you pushed a tablecloth from each side until it buckled.

James Smith, writing in the Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society in February 1846, expressed the opinion that Gibraltar should really be classed as “belonging to the coal measures” in view of the organic remains there being indicative of the Jurassic era. He admits to being uncertain, though, because of the lack of clear evidence. “Fossils are of such rare occurrence and in such an imperfect state,” he wrote, “that no certain inference can, in the present state of our knowledge of its organic remains, be drawn from them.” There are coal measures just to the north, too, but of small size and poor quality, more like shale than burnable deposits.

WHAT, NO RIVIERA?

However, the lifting of the Rock through continental drift not only had the effect of lifting and turning that crustal fold but also of sealing off the entrance to the Mediterranean. It happened around 6-million years ago, and for the next one-and-a-half million years the Mediterranean dried up completely, partly because an ice age froze so much of the sea. Then, around four-and-a-half million years ago, the ice caps started to melt and sea level eventually rose high enough for waters from the Atlantic to roar back through the widening gap. This created an area of sea in which Greeks, Romans and Barbary pirates could sail and across which the various forces called to help Menelaus and Agamemnon to besiege the city of Troy would row their warlike boats, full of warriors. It also became, of course, Homer’s “wine-dark sea” (οἶνοψ πόντος), in which Odysseus and his unfortunate crew got lost on their way home to Ithaca (although his seven years as a prisoner of the beautiful Calypso on the island of Ogygia, during which time he fathered two sons with her, Nausithous and Nausinous, must have had its more enjoyable side. As Calypso was supposed to be the goddess of silence it would have been fairly quiet, too. What a hard life these classical heroes had). Eventually, of course, the sea would also provide soft beaches, swept by balmy breezes and flanked by palm trees and expensive hotels, upon whose sands, starlets could gain a tan while being photographed, reluctantly-on-purpose, by the paparazzi and where luxury yachts could bob gently by piers, hosting cocktail parties for the well-heeled glitterati without ever having to put to sea.

FORTRESS GIBRALTAR

Although Spain will continue to argue for taking complete control of Gibraltar, the territory’s official language remains English, although most citizens are at least bilingual, speaking Spanish as fluently as they do English. Locally, many people speak Yanito, an Andalusian-based creole language with many English, Italian, Hebrew, and Maltese words. The territory also boasts shops familiar to a British high street, such as Marks and Spencer, Morrison’s supermarket and others, although with so many familiar shops in the UK closing forever because of restrictions imposed over the Covid-19 virus, the future cannot be certain for many of them.

It cannot be certain, either, for the Gibraltarians. Few in number though they be, they presumably matter to the British government and its baying nationalist media. Unlike his hero, Churchill and his bid to increase the number of macaques, however, British Prime Minister Boris Johnson has not ordered anyone, ministerial or otherwise (Britain no longer has a Secretary of State for the Colonies, of course) to encourage human Gibraltarians to increase their numbers through a breeding policy. He hasn’t even visited himself to see if anything can be done to boost the numbers.

During the war, the Gibraltarians themselves were evacuated, initially to Casablanca, which at that time seems to have been a very far cry from the place where Humphrey Bogart met his former screen lover, Ingrid Bergman, at Rick’s Bar and where the policeman played by Paul Henreid served a useful turn, aiding their sad separate getaways. The French, who had surrendered to Nazi Germany in 1940, were not happy at being saddled with refugees. In fact the Vichy French, sympathising with Berlin, were minded to get rid of them. This proved possible when fifteen British cargo ships arrived carrying French forces evacuated from Dunkirk. The French seized the vessels and refused to release them until their captains agreed to carry away the unwanted refugees, something forbidden by the British Admiralty, although the commander in charge relaxed the rule when he saw them being herded through the dockyard gates at bayonet point by French soldiers. They were allowed to take on board only what they could carry and no supplies, largely because the French were still angry at the attack by the British Mediterranean Fleet on Mers-el-Kébir, on the coast of French Algeria, to stop France’s warships from falling into German hands. Unfortunately, the British attack also killed over a thousand French sailors, so there was a lot of understandable bad feeling. The Gibraltar refugees were taken home but were only allowed to stay briefly while an alternative destination was found.

Inevitably, many ended up in Britain, but with accommodation limited, some 2,000 were moved on to the Portuguese island of Madeira. Those that remained in the UK were mainly housed around Kensington in London under the care of the Ministry of Health, from where they sent harrowing reports about the nightly bombing raids on London to relatives still living in Gibraltar. Some groups were also moved to refugee camps in Scotland and Northern Ireland. In 1940, a majority of the Madeira refugees were shipped home to Gibraltar, only to be evacuated again later in the same year, this time to Jamaica. Once Italy surrendered in 1943, objections to repatriation lessened and the long business of getting people home began, although there were inevitable delays and some did not get home until 1951, having been absent for around 10 years. In Jamaica, more than a hundred babies were born to the Gibraltarians during their exile there and parts of the special camp in which they were housed were converted into the University of the West Indies.

The real reason for the evacuation was not just to save the locals from enemy action but to create space for British and allied forces. Gibraltar played a key part in the Battle of the Atlantic and in the Mediterranean and Middle East Theatre. It was from Gibraltar that the British Navy provided escorts to vessels carrying supplies to the besieged island of Malta. During the war Gibraltar was bombed by the Vichy French and by the Italians. It also suffered underwater attacks by Italian commandoes. Inside the Rock itself, more caverns were excavated to make room for barracks, offices and a fully equipped hospital. German plans to invade Gibraltar were delayed until after the defeat of the Soviet Union, which never happened, of course.

Russia proved a much tougher nut to crack than Adolf Hitler had ever imagined. The arrival of the victorious Red Army in Berlin must have come as a bit of a shock for all those who had supported the Nazi party. After what the Russian troops had seen done by the Nazis as they progressed through Russia, their savagery when they reached Germany will come as no surprise.

Franco had assured Berlin that he had a force ready to take Gibraltar, but when his agents reported on how well it was defended and he realised the damage that could be done to Spain’s economy by a blockade of Spanish ports, he changed his mind. Hitler was not pleased, so his plan to take Gibraltar would have involved German forces ignoring Spanish sovereignty.

But it never happened, although the attacks on Gibraltar continued, and it remained the staging point for further attacks on Nazi positions. It was from Gibraltar that Lieutenant General Dwight D. Eisenhower travelled to North Africa to lead Operation Torch, devised to neutralise Italy by taking over the French colonies of Morocco, Algeria and Tunisia, from where attacks on Benito Mussolini’s forces could be staged, as well as to reach and take control of the Suez Canal.

In 1942, after his victory at El Alamein, British Lieutenant-General Bernard Montgomery became ground commander of the Anglo-American forces under Eisenhower. The two men never really got on, partly because a wound to his lung during World War One left Montgomery with a hatred of smoking, while Eisenhower smoked all the time.

Montgomery’s only connection with Gibraltar, however, is that it was where the Australian actor Meyrick Clifton James, acting as his double, was flown to fool German spies into believing an attack on the European mainland would start well away from Normandy. Germany knew that Montgomery – described by one colleague as “unbeatable and unbearable” because of his prickly personality – would be at the forefront of any allied invasion. After having breakfast with the Governor of Gibraltar, watched by a known Spanish spy for Germany, Clifton James was flown to Algiers and a very public tour of the airport, before being hidden in Cairo until the real Montgomery turned up in France, immediately after D-Day.

WHERE TO NEXT?

This, of course, is all history. Gibraltar played a huge part in the defeat of Nazi Germany and its citizens paid a very high price for that victory. The people of the United Kingdom should be grateful; they probably were, but as the American journalist Joseph Alsop wrote in an article for The Observer newspaper in 1952, “Gratitude, like love, is never a dependable international emotion.” Just as UK citizens are suddenly finding that the departure from the EU for which they voted (albeit by a fairly narrow majority) now means customs forms to send parcels into the EU, along with health certificates for animal products and other bureaucratic obstacles for exporters, it’s all beginning to look rather more complicated than the government politicians and the bulk of the media had promised.

The Gibraltarians did not want to see huge queues of trucks blocking the access route from Spain, nor did they want to see their airport converted into a parking lot for trucks. Being promised something by a government insisting on radical change at all levels is all very reassuring but the devil, as they say, is in the detail. You may recall a song by the Rolling Stones, which was issued as the ‘B’ side to Honky Tonk Women. Written, of course, by the inimitable Mick Jagger and Keith Richard, the chorus ran:

“You can’t always get what you want

You can’t always get what you want

You can’t always get what you want

But if you try sometimes you just might find

You get what you need”

That, of course, is what the people of Gibraltar have been hoping for and have probably got, although it may not be quite what the Brexit campaigners expected. After all, Chief Minister Picardo had said that a borderless arrangement with Gibraltar joining the Schengen area “would be most positive” for his territory. It is already clear that Gibraltar’s citizens will not share in any advantages arising from the trade deal between the UK and the EU. However, Picardo said, “We anticipate that those who are residents of Gibraltar, of whatever nationality, will have the ability to enter and exit Schengen like Schengen nationals, and those who are not resident in Gibraltar or the rest of the Schengen area, will then have to go through the third country national check.” That, of course, includes citizens of the UK.

Arancha Gonzàles Laya, Spain’s Foreign Minister, told journalists that Gibraltar will not be considered part of European air space and its inhabitants will no longer have access to Spanish social security funds. In addition, they will have to obtain special endorsements to their driving licences and pay extra for vehicle insurance. Another stalling point was the plan to allow the EU’s border agency, Frontex, to take over control of passengers passing in and out through Gibraltar’s ports and airport. Madrid still wants them to be answerable to Madrid, because Spain will be responsible for ensuring that Gibraltar continues to apply the rules required under the Schengen agreement, but no-one is saying if they will be or not. Picardo told journalists that there will be an increasing responsibility for Britain’s Borders and Coastguard Agency in Gibraltar once the Frontex teams are deployed, “not least because the agreement will open up opportunities for flights from the Rock to Schengen countries.”

The Government of Spain has agreed a temporary decree on the status of Gibraltar and its citizens, since they were deliberately omitted from the trade deal between the UK and EU, which will allow Gibraltarians to continue to hold jobs in Spain’s public sector, as well as to work in professions requiring EU residency and to study at Spanish universities. However, there had been a very real risk that without an agreement, Spain’s border with Gibraltar could have become an external EU border, with none of the (admittedly fairly scant) advantages that UK citizens will have. However, the temporary deal will have to be subject to a separate treaty between the UK and the EU. What has been agreed protects fluidity at the border, while Gibraltar, unlike the UK, will retain access to Europol databases and EU information systems. If the treaty is finalised the border fence will come down, according to Gonzàles Laya. The border will see other radical changes, too, once everything is agreed. Will it be safe? Picardo says it will be safer. “We will have more electronic surveillance than we do today,” he told journalists. Gibraltar’s airport and seaport will become external borders of the EU, although according to the Gibraltar Chronicle, none of the parties to the deal were prepared to say how Frontex will operate over the temporary period.

Picardo said that no Spanish officers would be present in Gibraltar.

WHAT’S THE BETTING?

As reported in the Gibraltar Chronicle at the end of December 2020, “Chief Minister Fabian Picardo had urged the UK and Spain to ‘defeat 300 years of history’ and seal a post-Brexit deal for Gibraltar that protects frontier fluidity in the interests of citizens on both sides of the border.” Picardo told the newspaper that a mutually accepted settlement would be important not just for Gibraltar but for the entire region. “It’s not just us that need a resolution to that issue,” the Chief Minister said. “Cross-frontier workers need a resolution to that issue as well, whether they are current cross-frontier workers or whether they are future cross-frontier workers. The whole region, if we are to create this area of shared prosperity, needs a deal to create that shared prosperity. In other words, we need the deal to go further, to do more, to provide more from the economic engine that is Gibraltar.” Gonzàles Laya stressed that the talking would go on to the very last moment, and it did. Before agreement was reached, she said “What is in play for this territory, which voted to remain within the EU, is that they could be the ones who the pay the price of the UK’s failure to reach a deal. They are going to end up outside, and it is very cold outside the EU.” Boris Johnson hailed the UK’s trade deal with the EU on Christmas Eve as “his Christmas present to the British people”; an odd present, perhaps, as it leaves them with less than they had inside the EU except for the right to wave a Union flag and sing “Rule Britannia” a little louder. The super-rich can also profit from doing business outside EU jurisdiction. In any case, Johnson’s largesse clearly didn’t extend to Gibraltar.

The Cross Frontier Group, made up of businesses and trades unions on both sides of the border, wrote to Picardo, Britain’s Boris Johnson and Spain’s Pedro Sánchez, urging them to find a solution. “As you will be aware,” they wrote in a letter since made public, “there is an interdependence not just only on the economic side, but also socially in this area, as can be expected of neighbouring populations that are forced to understand each other in order to live together. These ties that unite us make it necessary for pragmatism to reign in the negotiations and for the interests of citizens to be placed above any other issues.” Any agreement, of course, involves an element of compromise, something that was in short supply during London’s negotiations with Brussels. The letter reminds the leaders that “the main objective of a government is to respond to the demands and aspirations of its people, especially when these are legitimate and reasonable, such as those of the Gibraltarian and Campo-Gibraltarian citizens, reason why, [sic] we reiterate our call for an agreement that allows us a peaceful coexistence and common development between the communities that populate both territories.” That, it seems, is what they got, even if the details remain partially secret because negotiations will continue. And yet, with so much at stake for Gibraltar, there was always the glimmer of hope that common sense would prevail. One of the mainstays of Gibraltar’s economy is the on-line gambling industry. I wonder how much has been bet on obtaining an outcome favourable to Gibraltar? Unless they had failed to hit the jackpot with a workable deal the people of Gibraltar stood to lose more than their shirts. Perhaps the Barbary macaques should have warned them.