President of Cyprus Nikos Christodoulides in June 2023 in Strasbourg, France © European Union

The Republic of Cyprus has a new president: Nikos Christodoulides, the former foreign minister who won the election on 12 February 2023. At 49, he is the youngest head of state ever to lead the divided island nation in the Mediterranean. He narrowly defeated Andreas Mavroyiannis, a Communist-backed diplomat, with 51.92 per cent of the vote in a second round of voting.

His victory, however, was not without drama and uncertainty. Christodoulides, who ran as an independent, was supported by centrist parties skeptical of the UN-led efforts to reunify the island, which has been divided along ethnic lines since 1974.

That year, Turkey invaded Cyprus after an Athens-backed coup attempted to unite the island with Greece. Turkish and Greek Cypriots now live on opposite sides of a buffer zone controlled by UN.

Many feared that Christodoulides’ tough stance may complicate a lasting solution to the long-running conflict that has bitterly divided Cyprus, the EU’s easternmost member. However, Christodoulides has already met with Ersin Tatar, the Turkish Cypriot leader and has announced that a solution to the ‘Cyprus problem’ is his top priority. He has also promised to crack down on corruption as the island faces the fallout from a scandal involving the sale of passports for cash and serious allegations of money laundering involving Russian oligarchs that have somewhat tarnished the country’s image.

Cyprus’s geographic position and cultural closeness to Greece accounts for why 77% of the country’s population are Greek. This connection however became a problem for the country when Greek sovereign bonds were downgraded by credit rating agency Standard and Poor’s to junk status in 2010. The Cypriot government and banking institutions suffered a big loss because of their large exposures to Greek debt.

Like most countries, Greece had to resort to debt to finance its spending. However, low government revenues due to rampant tax evasion, generous social security and pension payments, and unrestrained spending finally backfired when the global financial crisis erupted in 2007-2008. The problem-laden Greek economy was further impacted when tourism and shipping, the country’s primary industries, suffered greatly due to the economic downturn. Over in Cyprus, despite austerity measures, the country also plunged further into recession. In 2012, the country’s GDP shrank by 2.3%. To cover its budget deficit, Cyprus asked for help from Russia and was granted a €2.5 billion emergency loan, subject to a 4.5% interest per year.

But the Russian support barely had an impact to improve the country’s declining economy. Consequently, credit rating agencies also downgraded Cypriot sovereign rating to junk status. This further increased the country’s borrowing cost, leaving the government with no choice but to seek a bailout from the European Union. During the latter part of 2012, multiple discussions took place regarding the conditions of the bailout. The European Union required strict austerity measures, such as reductions in civil service pay, social benefits, and raised taxes on tobacco, alcohol, fuel, property, and lottery winnings, as well as increased charges for public healthcare, in exchange for financial support. It was not surprising then, that the Cypriot population did not easily agree to these terms, and protests arose in opposition to the proposed plan.

Although the European Union and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) eventually approved the Cyprus bailout plan in March 2013, the vulnerabilities caused by the financial crisis exposed the country to other dangers.

| Russia steps in

Russia has often been accused of using illicit financial transfers, corruption and other organised criminal activities as instruments of economic influence. Although it is generally not easy to link these alleged financial transfers directly to the Russian government, in many cases they can be traced to Russian-owned individuals, companies and other networks with links to the Russian state.

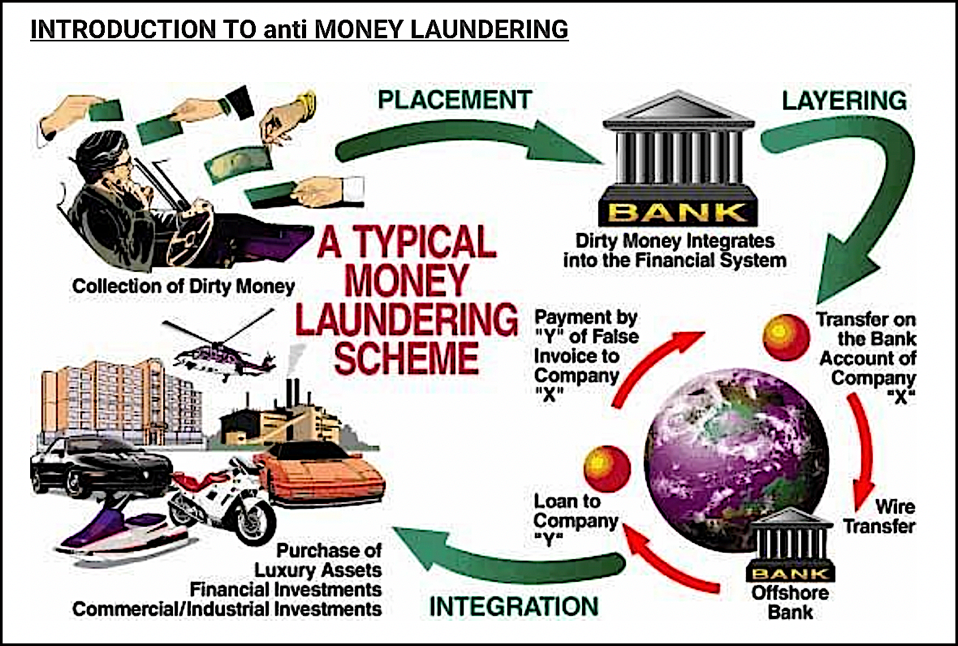

Money laundering schemes can be used to move funds illegally acquired in Russia out of the country and then used to purchase real estate or other legal goods and services, transforming them into seemingly legal assets. Such ‘dirty’, or even ‘clean’ money, transferred abroad can be used to finance corruption or other illicit business in the destination country that furthers Russia’s geopolitical interests.

In the Mediterranean, there are numerous examples of allegedly illicit Russian money flowing to both legitimate and illicit businesses, particularly along the northern littoral states. However, Russian money had, until recently, no larger destination in the Mediterranean than Cyprus.

At the time of the country’s financial crisis in 2013, there was an estimated $32 billion in Russian cash in Cypriot banks, more than the country’s annual gross domestic product (GDP) at the time. Russian bank loans to Russian-owned companies registered in Cyprus totaled another $30–$40 billion. The Carnegie Endowment for International Peace is renowned for its independent analysis of major global events and understanding of regional contexts. Joanna Pritchett, a former visiting scholar at the organisation estimated Russia was the source of 25 percent of inward and outward foreign direct investment (FDI) flows in Cyprus at the time, as Russians “roundtripped” their money between the two countries.

Russians lost billions of euros in the bailout of Cyprus that followed the 2013 financial crisis, but the EU’s bailout conditions converted some of those losses into shares in Cypriot banks, unintentionally giving some control over these banks to the Russians the EU had been trying to force out. But Even after the large losses from the 2013 financial crisis, Russian money continued to flow to Cyprus.

However, the situation changed drastically following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The US and its allies, imposed sanctions on companies, oligarchs and officials linked to President Vladimir Putin. Media reports highlighted the assets of Russian oligarchs that were seized across Europe, such as yachts in Italy, villas in the south of France and priceless works of art in Germany. But these are relatively easy to find. The real challenge is to track down the billions of dollars that the oligarchs have hidden around the world.

And this challenge led investigators to Cyprus, among a number of other strategic locations around the world. This small Mediterranean island at the crossroads of Europe, Asia and the Middle East that was a holiday hot spot, became the centre of an international game of hide and seek.

Leonidas Malenis, the renowned Cypriot writer and poet who passed away in December 2022, famously called Cyprus “a golden green leaf, thrown into the sea”.

The island, with its beautiful sandy beaches, has a very rich history. According to one legend, it was here that Aphrodite, the ancient Greek goddess of love, beauty and passion, emerged from the blue waters of the sea. But today, the island of the gods has become a stomping ground for wealthy Russians.

Limassol, a city on the southern coast of the island, was a popular destination for sun-seeking Russians before Vladimir Putin launched his full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Just a three-hour flight from Moscow, Limassol’s combination of designer shops, fur stores, Cyrillic signs, and caviar-serving restaurants earned it the nickname “Moscow on the Med.” It was in fact after the collapse of the Soviet Union that oligarchs first began flocking to the island. However, it was neither the beaches nor the historical monuments that attracted them.

Alexandra Attalides, a Cypriot activist and MP, was one of 12 individuals worldwide recognised by the US State Department for their efforts to fight corruption. In May 2021, she was elected to the House of Representatives as a member of the Greens and was named an Anticorruption Champion by US Secretary of State Antony Blinken, along with activists from Bulgaria, Malawi, and Thailand.

Attalides explains, “After 1989, when oligarchs seized the property of the Russian people and began building their empires, they may have feared that something might happen someday. So, they sought to safeguard their assets outside of Russia by looking for tax havens. At the time, we had a very low tax rate.”

A service industry that gradually prospered was established, specifically to draw in investors from abroad, and companies with ties to Russia.

Maira Martini, an analyst for Transparency International, a global non-profit organisation that monitors money laundering and works to end corruption in over 100 countries, says that for decades, Cyprus was hard to beat for oligarchs or other shady individuals looking to hide their rubles. She explains, “Cyprus historically built a financial system to attract foreign wealth. It offers both secrecy and security, which is what criminals and corrupt individuals usually seek. For many years in Cyprus, you could open a bank account or found a company without facing many questions, meaning you could deposit money without having to disclose your identity or the source of the funds.”

Cyprus became as famous for its opaque banking system as for its beaches and turquoise waters. Like sun-seeking tourists, foreign money soon flooded the island. By 2012, the country had amassed nearly €72 billion in bank deposits, with about 30% of those deposits coming from Russian nationals.

In 2013, however, the situation changed. The debt crisis in neighbouring Greece threatened to destroy the Cypriot economy. To prevent the loss of all Russian capital, legislators promoted a ‘citizenship by investment’ programme, a system used by other countries to attract wealth.

The programme worked as follows: any foreigner who invested more than 2 million euros in the country, usually by purchasing real estate, could obtain a Cypriot passport. This was a highly sought-after possession because Cyprus is of course, a member of the European Union.

From 2013 to 2020, Cyprus issued nearly 7,000 so-called ‘golden passports’, with almost half going to Russians. The Limassol skyline was suddenly dotted with high-rise luxury apartments, its port filled with mega yachts, and its stores frequented by ultra-wealthy Russians. However, in 2020, an undercover investigation by Al Jazeera revealed high-level corruption in the passport programme.

Cyprus had illegally issued hundreds of these ‘golden passports’ to criminals and fugitives. Following protests and pressure from the EU, the Cypriot government was forced to shut down the programme weeks later. However, the passports were still in circulation, and by issuing these documents to criminals, Cyprus had opened the door to Europe. However, these passports also provided access to Russian elites. At least a dozen now-sanctioned Russian oligarchs were issued these passports.

Among the recipients of a ‘golden passport’ was Igor Kesaev, a Russian billionaire and businessman. He is the owner and president of the Merkur Group, which includes the Megapolis Group, Russia’s leading tobacco retailer. Kesaev also owns arms manufacturers and a chain of retail stores. He is said to have close links to the Russian government and security forces such as the FSB and the GRU.

Another recipient of the passport was billionaire Alexander Ponomarenko, who served as the chairman of the board of Russia’s largest airport. The US government describes him as one of Putin’s ‘enablers’.

The list also includes aluminium magnate Oleg Deripaska, a member of Putin’s inner circle. According to the US Treasury Department, he has been under international investigation for money laundering, illegal wiretapping and extortion, among other things. However, like most other oligarchs involved in these affairs, he denies the charges.

Maira Martini says that a Cypriot passport could make it easier for sanctioned oligarchs to purchase property and move assets. She also expressed concern about the close relationship between wealthy Russians and Cyprus, which is raising alarm internationally.

Martini adds, “If you are a small country that is very dependent on foreign money from a single country, this could even lead to conflict, right? Sanctions are only as strong as the weakest link, and I think Cyprus is one of the weakest links”.

In September 2022, then-Minister of Finance Constantinos Petrides announced that the passports of sanctioned oligarchs were being revoked and that Cyprus had seized 105 million euros of Russian deposits. While this is a significant amount, it represents only a small fraction of the estimated 5.6 billion euros in Russian deposits made in Cyprus in 2021 and 2022. He also added that the numerous properties and active shell companies that had been traced back to sanctioned Russians had been placed under increased scrutiny.

However, more often than not, Russian oligarchs do not list their names in connection with their assets. For

example, according to US investigators, Roman Abramovich’s planes were hidden under five shell companies, stacked like Russian nesting dolls, with addresses in the British Virgin Islands and the island of Jersey, all leading to an anonymous trust in Cyprus. However, it was not Cypriot authorities who ultimately moved to seize the planes; it was prosecutors from the US Department of Justice.

Data released by the Bank of Russia in 2019 showed that Russia’s foreign direct investment (FDI) in Cyprus accounted for 50 per cent of all FDI positions worldwide. Some of this investment was subsequently transferred to other parts of the European Union, making it difficult to trace back to Russia.

Money flowing from Russia into and out of Cyprus included both legitimate transfers and those used to finance criminal activities. For example, funds stolen from the Russian treasury were channeled through the now defunct Federal Bank of the Middle East (FBME) in Cyprus, and then used to manufacture chemical weapons in Syria.

For a long time, analysts had expressed concern regarding the influence that Russia exerted on Cyprus’s policymaking and politicians through the significant inflows of money and people. The inclusion of Russian citizens in the country’s voter rolls could undeniably have impacted future elections and decision-making processes within the government.

And to pursue this goal, Russian emigrants had even established a political party in Cyprus.

In September 2017, the announcement of the formation of ‘I, the Citizen’, created by Russian expatriates holding Cypriot passports was seen as one of the most contentious political movements in the island’s history. After months of review, the Interior Ministry granted approval of the new party. Its leader was announced as Alexey Voloboyev, a businessman who operated a restaurant in Limassol and had previously funded a Russian radio station in Cyprus.

A case that highlights the influence of Russian money in Cyprus involves William Bowder, an American-born British financier and anti-corruption activist. He is the CEO of Hermitage Capital Management, the investment advisor to the Hermitage Fund, which at one time was the largest foreign portfolio investor in Russia. Bowder accused a Cypriot government official of aiding a Russian mobster in laundering money through a property purchase in Cyprus.

In a more significant example, no arrests have been made in the FBME bank case. While Cyprus did not obstruct the EU’s semi-annual renewal of sanctions on Russia for its aggression in Ukraine, which some had feared, decisions such as the 2015 agreement allowing Russian naval ships to access the country’s ports demonstrated the extent to which Russian money could have an impact.

US Deputy Attorney General, Lisa Monaco is responsible for the Department of Justice’s ‘KleptoCapture Unit’, which is tasked with locating the assets of sanctioned oligarchs hidden around the world. She acknowledges that hidden wealth is no longer whisked away by people fleeing with suitcases full of banknotes. It is rather consists of cryptocurrency, hidden planes and yachts, and highly layered assets. However, she is certain of one thing: “Even for the most notorious actors, whether it’s the mafia or rogue regimes, the best tool we have is following the money.”

The money trail has led Department of Justice investigators around the world and closer to home. Like the tourists who visit Cyprus, dirty money doesn’t remain on the island forever. It is typically ‘laundered’ and invested in other Western economies. Investigators say this is one way Oleg Deripaska has been able to evade sanctions. Lisa Monaco adds, “what the task force exposed was the network of enablers and money launderers, as well as facilitators who helped him hide his wealth in real estate here in Washington D.C., in Manhattan and other places in the United States…in works of art, in vanity businesses, including a music studio in Beverly Hills”.

In their case, the Department of Justice alleges that in 2020, Oleg Deripaska spent hundreds of thousands of dollars to arrange for one of his children to be born in the United States, even though he was under U.S. sanctions. As a result, that child is now a US citizen. Deripaska tried to do the same thing a second time, but US Customs managed to prevent that attempt.

The government case details how, as the war in Ukraine intensified, Deripaska used a Cypriot company to arrange travel on a private jet from Russia to Los Angeles for his pregnant girlfriend Ekaterina Voronina, moving money to rent a home for her in Beverly Hills. But when she landed in Los Angeles in the summer of 2022, she was stopped by customs officers. Voronina had lied to the Department of Homeland Security to conceal her ties to the Russian oligarch.

Announcing the indictment in September 2022, Lisa Monaco said, “Derpaska sought to evade sanctions through lies and deceit to cash in on and benefit from the American way of life. But shell companies and webs of lies will not shield Deripaska and his cronies from American law enforcement, nor will they protect others who support the Putin regime. The Department of justice remains dedicated to the global fight against those who aid and abet the Russian war machine”.

Deripaska, his girlfriend and the U.S. resident who helped him are now charged with sanctions evasion. They are not in custody, but the Department of Justice has announced plans to seize his U.S. properties worth an estimated $70 million.

Back in Cyprus, investigators found a luxury villa in Paphos, west of Limassol, as well as more than a dozen active shell companies linked to him.

| Credibility must be safeguarded

In April 2023, just one month after newly-elected president Nikos Christodoulides assumed office, Cyprus faced another Russia-linked crisis, as policymakers tried to contain the damage, panic was palpable, and meetings followed one after another. Christodoulides talked with real urgency about the need to clamp down on sanctions violations if Cyprus is to protect its credibility as a business hub.

Following a series of reports that raised concerns about sanctions enforcement in Cyprus, UK and US authorities issued lists that contained 13 Cypriot entities and individuals who purportedly aided Russian oligarchs. The measures aimed to disrupt the financial networks of Vladimir Putin’s close allies, Roman Abramovich and Alisher Usmanov. Their ‘financial fixers’ had their bank accounts and other assets frozen overnight. The people named included two dual Uznek-Cypriot nationals, three Russian Cypriots and a Russian man with dual Israeli-Cypriot citizenship.

Following the publication of The Oligarch Files – a series of reports that raised doubts about sanctions compliance in Cyprus – by the Guardian newspaper, the Foreign Office took action.

The British government said Cypriot companies, including a prominent law firm, had helped Uzbek-born Usmanov, who is on both UK and US sanctions lists, manage ownership of a 16th-century Tudor manor in Surrey, England. According to a spokesperson for Usmanov, ownership of the property was long ago transferred to an irrevocable trust, and beneficial rights given up to the trust, donating them to family members.

The allegations have been very embarrassing for the new government in Cyprus with well-informed sources talking of panic in the island’s financial services sector.

Soon after this, hundreds of firms reportedly hurried to distance themselves from sanctioned Russians amid media reports that Kremin-linked businesses also began to seek refuge from possible restrictions, in the island’s separatist Turkish-controlled north. Unlike the internationally recognized south, the de facto mini-state in the north is outside EU jurisdiction.

But the British and American sanctions also conveyed another message: that the issue at hand was “Cyprus’ name as a reliable, financial and business centre”, as the Greek Cypriot government spokesperson, Konstantinos Letymbiotis put it. The country’s financial integrity seemed to be in jeopardy again, a decade after it barely escaped economic ruin in a banking crisis that revealed its dependence on Russian money, as the EU’s easternmost member.

President Christodoulides was irritated by the new sanctions that named the 13 individuals, which underlined his country’s firm Western alignment amid Russia’s war in Ukraine. Christodoulides said that he was “sending out the clear message that our country’s credibility must be protected and we must in no way allow or enable anyone to tarnish the name of our country”. Shortly later, a national unit for implementing sanctions was declared, and the government spokesperson stressed that “no violation of EU sanctions will be tolerated”. The UK is to provide technical support for the new unit.

On 21 April, the country’s largest lender, the Bank of Cyprus, declared that about 10,000 accounts in the names of 4,000 Russian depositors would be shut down, amid rumours of more sanctions lists from London and Washington against Cypriots and Cyprus-based companies, to further sanction Russia for its war in Ukraine.

The depositors who hold Russian passports and are not residents of an EU country were informed by the Bank of Cyprus that their accounts will be shut down. The bank added that this action followed the suspension of Russia’s membership by the Financial Action Task Force and the identification of Russia as a non-cooperative tax jurisdiction by the EU.

The account closures were viewed as going “further than” restrictions on Russian bank holders in other EU countries, where depositors have had their transfers restricted – with transactions over €100,000 prohibited – but have not been obliged to close down accounts. The Russians were granted two months – a notice period known as standard bank procedure -to seek other alternatives.

Financial analysts in Nicosia are of the opinion that the bank’s concern of being regarded as violating sanctions – and possibly ending up on the US Department of the Treasury’s list of specially designated nationals and blocked persons – had certainly affected its decision.

Fiona Mullen, the director of Sapienta Economics, a consultancy firm in Nicosia said, “if the US stops a bank’s ability to trade in dollars, that bank cannot survive”. She further added, “I have been saying for a long time that the Republic of Cyprus needs to treat its reputation for international honesty as an existential issue just as it does the Cyprus problem”, referring to talks aimed at reuniting Europe’s only divided state.

Negotiations with the rebel Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus have been frozen since 2017. “I think the lesson has finally sunk in,” she said.

| Into the new era

Few countries have so deftly exploited geopolitical turmoil as Cyprus. After Turkey’s 1974 invasion following a coup aimed at union with Greece, the country’s ruined economy recovered amazingly after thousands of Lebanese, fleeing civil war, sought shelter in the internationally recognised south. During the Yugoslav wars, the island, by then a notorious tax haven – a status lost in 2019, when the corporate tax rate was raised to 12.5% – became the favoured place for the Milošević regime to launder money.

But following Cyprus’ endeavours in recent years to curb its reliance on Russian money – under pressure from US regulators who seek to not only curb Russian investment but the country’s influence in the region – bank accounts belonging to Russians have plummeted drastically. Only 2.2% of all bank deposits are held by Russians, a far cry from the tens of billions deposited in Cypriot bank accounts before the 2013 financial crisis. Cypriot authorities have not only closed 123,000 suspicious bank accounts but also about 43,000 shell companies.

As the country’s leader Nikos Christodoulides vowed to push ahead with the prosecution of law and audit firms that had aided Russian oligarchs, Washington released documents that amounted to a toolkit to facilitate the process. At least two other dossiers were expected to follow. Acknowledging receipt of the so-called “data package” on 9 May, President Christodoulides affirmed a new era had commenced in the EU member state long known as “Moscow on the Med” due to its financial ties with Russia, and reputation for slack regulations. “It’s essential we approach this issue with the appropriate seriousness and do what we can so as not to allow anyone to smear the country’s name,” he told a key economic forum in Nicosia. “And I am certain that you who represent our economy realise and share the need to conclude this matter and move into the new era.”

And the new era will demand a new statecraft. There may be some stormy waters ahead as President Christodoulides guides Cyprus into this new era.

This will by no means be an easy task. But the Cypriot people have inherited a legacy of courage and achievement from their Greek ancestors, and they need a leader who can harness their potential to solve the problems they face. President Christodoulides has promised to be that leader, and to work for the interest of all Cypriots, regardless of their ethnicity, religion, or political orientation.