Nuuk, capital of Greenland ©Wikimedia

Greenland—what a curious name! It sounds like it should be a lush, green paradise, but in reality, much of it is frozen and covered in ice. This remote land, situated at the extreme north of our planet, was once thought of as the legendary Hyperborea during the Renaissance—a harsh and mysterious place known for its lost Viking explorers, icy landscapes, and roaming polar bears. Until very recently, Greenland didn’t pop into the minds of most Europeans or Americans, except perhaps when President Donald Trump yet again showed interest in purchasing it from Denmark. This raises an intriguing question: how did a region so close to North America, where the inhabitants speak a language closely related to the Inuit languages of Canada and Alaska, come to be ruled by Denmark?

Greenland may have a tough climate, but it has an incredibly captivating history. It served as the first meeting point between the Old World and the New, where Inuit and Scandinavian cultures have blended since the Viking era. This vibrant story is still evolving as Greenland works toward greater autonomy and seeks to carve out its role in an ever-more connected world.

| VIKING BEGINNINGS

Before going into Greenland’s history, it is necessary to clear up a number of points that seem to have created some confusion as to who actually owns the territory. Greenland isn’t exactly a colony of Denmark, but more like a self-governing territory within the Kingdom of Denmark. Imagine it like a country within the United Kingdom – it has its own leadership, with a prime minister and parliament, and manages many of its own affairs.

The confusion arises from the nature of Denmark itself, which is a country in its own right but is also a larger entity that includes Greenland and the Faroe Islands; a kind of federation, with a shared monarch, Queen Margrethe II. This arrangement gives Greenland a degree of autonomy similar to that of the Channel Islands or the Isle of Man within the United Kingdom. This unique set-up allows Greenland to maintain a distinct identity, with its official language, Kalaallisut — the Inuit language — and its culture significantly different from that of Denmark. While Greenland has been part of the Danish Realm since 1814, Denmark has always recognised the importance of Greenland’s autonomy.

Figuring out who really owns Greenland is like trying to untangle a really complicated piece of yarn. There are three different groups that claim a right to it: the Danes, the Norwegians, and the Inuit people who live there. While the Inuit are undeniably Greenland’s indigenous people today, their arrival is a relatively recent chapter in the island’s story. Archaeological evidence suggests that the Dorset culture, an ancient Paleo-Eskimo society that existed in the Canadian Arctic and Greenland from around 500 BCE to 1500 CE and pushed out by the Inuit around 1200 AD, were the first human inhabitants. This pushes the potential window for Scandinavian claims back to the Viking Age, a period rich with tales of exploration and intrepid adventurers.

The Nordic claim to Greenland hinges on the establishment of Norse settlements in the 10th century. Erik the Red, a legendary Viking chieftain and explorer, is said to have landed in Greenland after Icelandic exile for murder, according to the epic saga named after him. Norse settlers, driven by a pioneering spirit, established three main settlements in Greenland, the communities surviving on livestock farming and hunting seals and walruses. Their reach extended beyond the southern tip, with Norse hunters advancing as far north as Disko Bay in pursuit of valuable walrus ivory. Between the 10th and 15th centuries, these Norse settlements flourished under Norwegian rule, solidifying a trade route for Greenlandic ivory into Europe.

| PROSPERITY UNDER NORWEGIAN RULE

These early Norse settlements in Greenland weren’t exactly self-made. For the first few hundred years, they were actually managed by Iceland, but as these Greenlandic communities prospered, they started to turn heads. The Kingdom of Norway saw a chance to expand its reach, as King Haakon IV wasn’t one to miss a good deal. Through clever negotiations, he managed to bring Greenland under the Norwegian crown in 1261.

This event proved to be a game-changer; Greenland suddenly had a direct connection to the rest of Europe, and things really boomed for the settlements. Greenland became a major supplier of walrus ivory, which was a hot commodity in Europe back then. Norway’s coastal cities and the British Isles became the main hubs for shipping this valuable treasure. Fuelled by the lucrative ivory trade, the Greenland Norse went on a building spree. Churches and convents popped up thanks to this newfound wealth. The St. Nicholas Cathedral, built in 1126 at Igaliku, in southern Greenland, and dedicated to the patron of seafarers is the oldest building of its kind in the entire Western Hemisphere. Archaeologists began digging up the site in 1926, and what they found was pretty fascinating. The oldest parts of the cathedral were built right on top of an ancient pagan shrine; they found 25 walrus skulls and 5 narwhal tusks buried there.

| DENMARK ENTERS THE FRAY

Greenland had a long history with Norway and Iceland, going way back to the days of Erik the Red. Denmark and Sweden were more focussed on expanding their power in the Baltic and Eastern Europe. So, neither country really paid much attention to Greenland for a long time. Then, in 1397, things changed. Queen Margarethe I of Denmark, a really powerful woman, managed to unite Denmark, Norway, and Sweden under one ruler – her grand-nephew. They called it the Union of Kalmar. This wasn’t like a single country, though. It was more like all three kingdoms having the same king, but still keeping their own governments and laws.

Greenland, which was part of Norway at the time, stayed that way under this union. The idea was that if Denmark and Norway ever split, Greenland would go with Norway. But then, a couple of big things happened between the 16th and 19th centuries that left Greenland under Danish control. It wasn’t until the 20th century that things really got sorted out.

Beginning in the 14th century and for the next 200 years, the Norse settlements gradually diminished until they were totally abandoned. Historians have speculated that one important factor was probably the Black Death, which swept through Europe and killed millions of people. The plague probably hit Greenland too, and with a smaller population already, it could have been very difficult to recover.

Then, things got even harsher with the “Little Ice Age”. According to researchers from NASA, this cooling period made it even harder to survive in the Arctic, and Greenland got cut off from Europe by all the extra ice. What’s more, the Vikings weren’t the only ones in Greenland anymore; newcomers called the Inuit arrived from Canada. Scholars generally agree that the decline in the demand for walrus ivory was a significant factor in the abandonment of the Greenlandic Norse settlements. Walrus ivory was a crucial trade commodity for the Norse, providing them with access to essential goods from Europe. However, as the market for ivory weakened, the economic viability of the settlements diminished, and the Norse gradually returned to Iceland.

The Inuit effectively governed Greenland, and European interest in the region waned until the voyages of Iberian nations to the Americas and Asia ignited a fervour for exploration, as European powers vied to establish colonies in the New World and locate the elusive Northwest Passage. Scandinavia, including Greenland, was swept up in this fervent exploration era, known as The Age of Discovery.

The Treaty of Tordesillas in 1494, designated Greenland as the exclusive domain of Portugal by papal decree, prohibiting other Catholic nations from colonising the island. With the rise of the Protestant Reformation, England disregarded papal pronouncements and expressed interest in the polar regions as a potential gateway to North America.

In the early 17th century, King Christian IV of Denmark-Norway, motivated by a desire to reassert Scandinavian control over Greenland before England or another European power could lay claim to it, commissioned three expeditions led by English captain James Hall. These expeditions aimed to locate any remaining Norse Greenlanders so as to establish Danish rule. While the search for the Eastern Settlement, the largest of the three Norse settlements, proved unsuccessful, the explorers’ accounts provided valuable cartographic data on Greenland, which would later prove instrumental in facilitating Danish colonisation efforts in the 18th century.

| NORWAY APPOINTS AN ENVOY

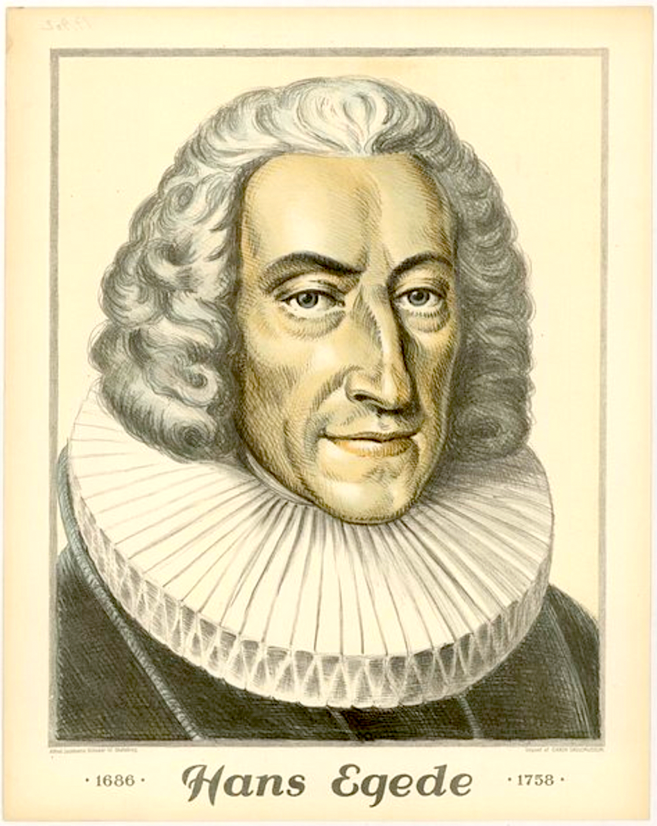

Navigational challenges in the icy waters of the North Atlantic and uncertainty regarding the location of the Eastern Settlement hampered Danish efforts to re-establish contact with Greenland until 1721. But, as the grip of the Little Ice Age loosened, Norwegian Lutheran missionary Hans Egede renewed the crown’s mission to locate any surviving Norse inhabitants.

Egede believed that some Norse might have persisted in Greenland, either maintaining their Catholic faith despite the Reformation or having abandoned Christianity entirely. After months of fruitless searching for Norse survivors, Egede encountered only Inuit populations. He then dedicated himself to learning the local dialect and introducing Christianity to the Inuit, laying the groundwork for subsequent Danish colonisation efforts.

The establishment of Godt-Haab (present-day Nuuk) on Greenland’s western coast by a group of Moravian missionaries injected new life into the colonial endeavour. Dutch whalers, Danish-Norwegian hunters, and Inuit converts soon followed, and the Danish settlements in Greenland began to expand, despite a devastating smallpox outbreak that claimed many lives, including that of Egede’s wife.

| DENMARK FINALISES GREENLAND’S INTEGRATION

Formal recognition of Danish control over Greenland and its de jure possession of the island would not occur until 1814. Ironically, this shift in Greenland’s status arose from a Danish defeat at the hands of Sweden during the Napoleonic Wars. Napoleon’s aggressive expansion across Europe compelled many smaller nations to choose sides in the numerous conflicts between the French emperor and the opposing coalitions. Denmark initially pursued neutrality, but a violent British attempt to preempt a potential French capture of the Danish merchant fleet ultimately forced the Danes to align with Napoleon.

Coincidentally, Napoleon’s general, Jean-Baptiste Bernadotte, ascended to the position of Swedish crown prince through marriage in 1810, and he would subsequently become king. However, following Napoleon’s decisive defeat at Leipzig in 1813, Swedish troops, with British endorsement, occupied Danish territory, prompting a swift surrender by King Frederick VI of Denmark. The resulting Treaty of Kiel in 1814 awarded Denmark control over the settled regions of Greenland, but the sovereignty of the entire island remained a contentious issue. Denmark had not undertaken any significant exploration or settlement efforts in the vast, uninhabited expanses of Greenland. This lack of comprehensive control left the island vulnerable to claims by other nations under the principle of terra nullius (nobody’s land), that has been used to justify claims that territory may be acquired simply by a state’s occupation of it.

The emergence of Norwegian claims in 1931, following the country’s regaining of independence in 1905, ignited a minor international dispute that was brought before the Hague tribunal, which ultimately ruled in favour of Denmark. These historically Norwegian territories remained under Danish control, establishing the geopolitical landscape that persists to this day.

| THE U.S. STEPS IN

While the symbolic Norwegian occupation of Greenland might have appeared inconsequential, Denmark’s anxieties stemmed from a very real threat posed by a far more powerful nation: the United States. This rising American power had ambitions to expand its influence into Greenland, either through diplomatic negotiations or, potentially, through the annexation of Arctic territories.

Following the successful purchase of Alaska from Russia for $7,2 million in 1867, the U.S. attempted to acquire both Iceland and Greenland from Denmark in 1868. The motivation stemmed from a U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey and Department of State report that catalogued the resources and economic potential of both islands. However, Denmark’s refusal to sell, thwarted American territorial ambitions in the Arctic until the early 20th century.

The late 19th and early 20th centuries witnessed a surge in polar expeditions, as explorers ventured into the Arctic to map and explore the region, setting the stage for a future race for territorial control. American explorers were among the first to chart Greenland’s interior, with some even attempting to claim portions of the island for the United States under the auspices of the Monroe Doctrine. To preempt a potential American takeover, Denmark strategically made recognition of Danish sovereignty over Greenland a condition for the sale of the U.S. Virgin Islands which had become Danish colonies in 1754, and were known as the Danish West Indian Islands. The United States accepted this demand in 1917.

| THE ROAD TO INDEPENDENCE

The United States renewed its efforts to acquire Greenland in 1947, offering Denmark a sum of $100 million in gold. However, Denmark once again declined the offer. As the Cold War tensions extended to the Arctic region, Denmark took steps to solidify its control over Greenland, and in 1953, the territory was formally incorporated as a Danish province by the Naalakkersuisut, the island’s executive cabinet. This decision integrated Greenland fully into the Danish national territory, but the German occupation during World War II forced Greenland to operate independently for the duration of the war. This wartime experience contributed to the rise of an autonomist movement, eventually evolving into a push for full independence.

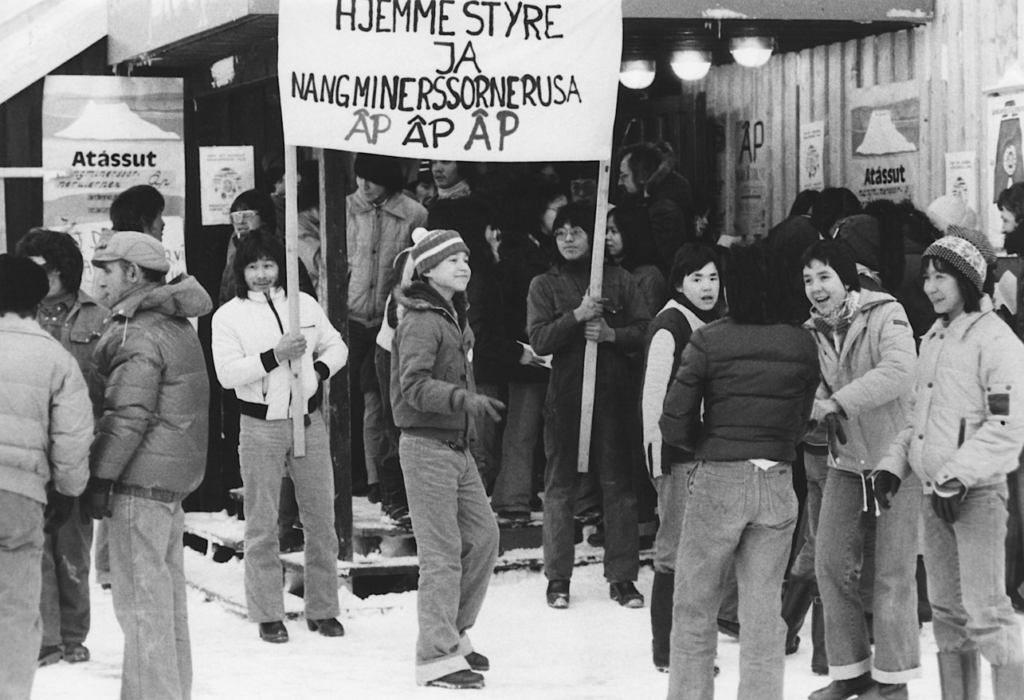

Greenland’s status transitioned from a Danish province in 1979 to that of a self-governing territory, following a public vote in favour of home rule. The significant cultural distinctions between Greenland and Denmark, with over 90% of Greenland’s population being Inuit, fuel strong sentiments in favour of independence. However, these aspirations are tempered by Greenland’s economic dependence on Denmark.

In 2008, Greenland enacted legislation granting itself greater autonomy from Denmark. Notably, Chapter 8, Section 21 of this law enshrines the right to self-determination through a referendum process. Public opinion on independence remains divided. While a majority of Greenlanders favour the theoretical concept of independence from Denmark, Danish newspaper DR reported that 78% would oppose independence if it resulted in a decline in living standards and the cessation of Danish subsidies.

In a 2020 interview with High North News, an online news outlet based in Norway, the then- Prime Minister of Greenland, Kim Kielsen, emphasised the need to diversify Greenland’s economy to prepare the country for potential independence, particularly in light of increasing efforts by the United States and China to expand their influence in the Arctic : ”The mandate we have from our people says that we must work towards independence. There should be no doubt that everything we do is part of this preparatory process. More than 70 percent of our population want us to move towards independence, and it is stipulated in the law on Greenland’s Self Rule how this must happen. That is the mandate we have been given and it has been with us for a very long time,”

| LOOKING TO THE FUTURE

The sudden resurgence of significant U.S. interest in Greenland, culminating in August 2019 with the confirmation by Donald Trump, during his first presidency, of his desire to purchase Greenland, including its 57,000 inhabitants, did not alter Greenland’s trajectory towards independence from Denmark, which retains sovereign authority over the island. Trump’s proposal was met with immediate criticism and confusion, both domestically and internationally, and his remarks were viewed as impulsive and lacking an understanding of the complexities involved in acquiring a territory where independence is an increasingly likely prospect, and which operates under its own government, independent of Danish involvement.

The Arctic Institute, a think tank headquartered in Washington D.C. has documented Greenland’s emergence as a focal point in international geopolitics in the growing rivalry between the United States and China. Chinese investments in the island’s hydrocarbon and mineral resources have become a source of concern for the U.S. due to Greenland’s strategic location near North America.

This explains why the longstanding dialogue with Denmark regarding lease agreements for specific parcels of Greenland, has turned into discussions about the acquisition of the entire territory.

Greenland plays host to Pituffik Space Base, which was formerly known as Thule Air Base. It was renamed in 2023 in recognition of Greenlandic cultural heritage and better reflect its role in the U.S. Space Force. The base holds the distinction of being the United States military’s northernmost installation, 1,210 km north of the Arctic Circle and 1,524 km from the North Pole.

This strategic location which was established during the Cold War is equipped with a radar and listening post that includes a Ballistic Missile Early Warning System, capable of detecting and providing advance warning of incoming intercontinental ballistic missiles. The threat of nuclear war was seemingly ever-present during this 45-year period.

Moreover, its surveillance reach extends thousands of miles into Russian territory, underscoring its critical role in global security and defence monitoring.

The world’s largest island possesses huge reserves of rare-earth metals used for a variety of high-tec applications, including electronics, electric vehicles, catalysts, medical applications and aerospace and defence. The receding Arctic ice cover also presents strategic opportunities for expanded trade via new sea routes, energy extraction and transportation within a region increasingly characterised by geopolitical competition among rival powers, China and Russia.

In January, the Wall Street Journal reported heightened U.S. interest in Greenland, with President Donald Trump again expressing an urgent desire to acquire the territory. This situation is probably best understood within the context of U.S. efforts to counter China’s influence and reduce reliance on Chinese technology components.

Be that as it may, President Trump proposed that Denmark should transfer its autonomous territory to the United States, arguing, “for purposes of national security and freedom throughout the world, the United States of America feels that the ownership and control of Greenland is an absolute necessity.”

Such statements naturally alarmed European allies and sent shockwaves through diplomatic circles, claiming that the idea that he might using military means to assert control over a territory belonging to a NATO ally contradicted the principles of collective security and mutual respect that underpin the alliance.

Denmark, as a member of both the EU and NATO, found itself navigating a challenging diplomatic landscape as the threats from the U.S. president created tensions not just between the U.S. and Denmark, but also within the broader context of U.S.-European relations.

Denmark’s government rejected Trump’s proposal, emphasising Greenland’s status as a self-governing territory, with its own parliament and exercising considerable autonomy over its affairs, although Denmark retains control over foreign policy and defence. The Danish Prime Minister, Mette Frederiksen, characterised the idea of selling Greenland as “absurd,” reinforcing the notion that Greenland’s sovereignty could not be negotiated like a real estate deal. While Greenland is not officially a member of the European Union, its designation as an overseas EU territory affords it unique advantages. This status allows Greenland to tap into EU funding opportunities and grants its citizens the rights associated with EU citizenship.

In response to the brewing tensions, Denmark sought to strengthen its ties with other European nations and reaffirm its commitment to NATO. The Danish government emphasised the importance of collaborative security in the Arctic, particularly in the face of increasing Russian military activity in the region.

| THE BIGGER PICTURE

Mikkel Runge Olesen, a senior researcher at the Danish Institute for International Studies highlighted Greenland’s escalating strategic significance amid the backdrop of geopolitical instability during an interview with Euronews: “If relations between world powers are good, in the Arctic specifically, then Greenland becomes less strategically valuable. So, as the U.S. gears up for more confrontation with Russia and China, Greenland’s presence becomes more important.” He then added, “American strategic interest in Greenland is as much about their own presence as it is about denying their rivals’ presence”.

Mikkel Runge Olesen, a senior researcher at the Danish Institute for International Studies highlighted Greenland’s escalating strategic significance amid the backdrop of geopolitical instability during an interview with Euronews: “If relations between world powers are good, in the Arctic specifically, then Greenland becomes less strategically valuable. So, as the U.S. gears up for more confrontation with Russia and China, Greenland’s presence becomes more important.” He then added, “American strategic interest in Greenland is as much about their own presence as it is about denying their rivals’ presence”.

As for Greenlandic Prime Minister, Mute Egede, he emphasised that the territory was not for sale and repeated again the fact that Greenlanders want to be neither Danes nor Americans. He insisted, “Greenland’s future is decided in Greenland, and by the citizens of Greenland”.

However, adopting a pragmatic perspective, the prime minister conveyed an optimistic outlook at a press conference held on 10 January. He expressed Greenland’s eagerness to enhance its partnership with the United Staes. He underlined the importance of upgrading cooperation in defence matters as well as delving into the rich mining resources that Greenland has to offer. This commitment reflects a more thoughtful approach to fostering closer ties and collaboration in the current global landscape.

In the meantime, Denmark’s Foreign Minister addressed President Trump’s renewed interest in Greenland during a press conference held in Jerusalem. Lars Lokke Rasmussen remarked, “I don’t want to engage in any disputes with President Trump.” He noted the U.S. President has a distinctive approach when it comes to articulating his requests, and emphasised that Denmark is currently entering a more in-depth dialogue with him.

Rasmussen acknowledged shared concerns regarding the security situation in the Arctic, stating, “We agree that the Americans have certain concerns about the security situation in the Arctic, which we share.” He further assured that Denmark, in close collaboration with Greenland, is prepared to continue discussions with Trump to safeguard and address “legitimate American interests.”

In conclusion to this exploration of Greenland, we find ourselves at a juncture where a rich history meets the urgent realities of today’s geopolitical landscape. The recent American interest—marked by both friendly overtures and pointed threats—has thrust this vast, icy territory into the global spotlight. With its immense natural resources and strategic significance, Greenland has silently witnessed the shifting tides of power for centuries. Now, as its people grapple with the challenge of maintaining their unique identity amidst external pressures, their future hangs in a delicate balance.

This story is not just about Greenland; it is about so much more. It touches on bigger themes like sovereignty, ambition, and the way different cultures interact. As we follow this narrative, it really hits home how history and our hopes and dreams can come together to shape not just a place, but entire regions and even the world at large. It is a powerful reminder of how interconnected we all are in this journey.

hossein.sadre@europe-diplomatic.eu