Norway’s ambitious west coast road scheme

By any definition, Norway’s plan to develop a continuous Coastal Highway between Kristiansand in the south and Trondheim in the north is a massive undertaking. The route of the present E39 road is 1,100 kilometres long, and it currently uses seven different ferry connections. What the Stortinget – Norway’s parliament – has decided is to cut the current 21-hour journey time substantially. The current road is about as far from being an autobahn as it’s possible to be, running through several towns and cities, including Stavanger, Bergen, Ålesund and Molde. The goal is to cut journey time by half and to shave 50 kilometres off the distance. Norway’s famous historical kings, Harald Fairhair and Harald Hardrada, would have been astounded.

General Norwegian

Public Roads Administration

© Vegvesen

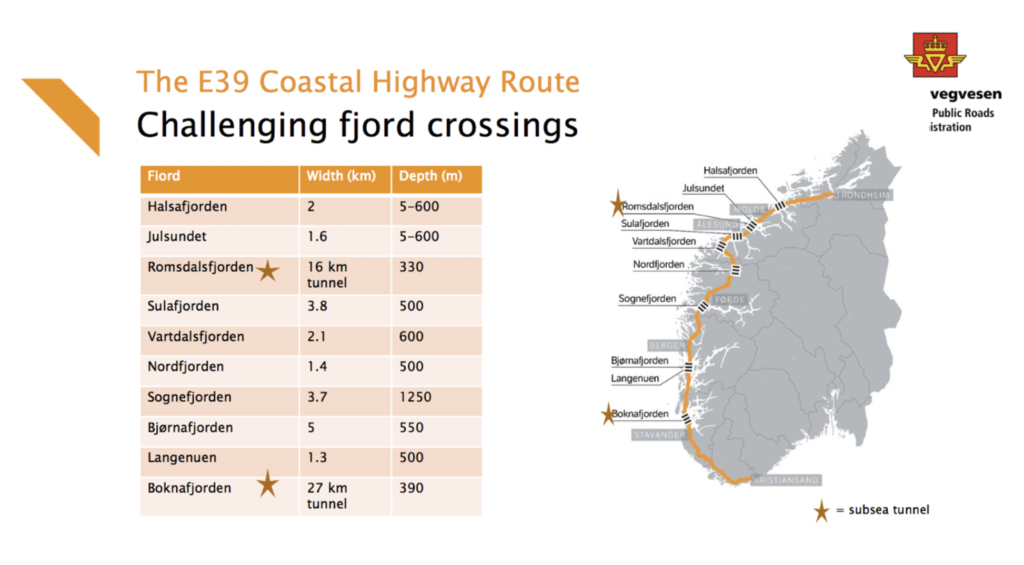

The plans to develop the route are part of the National Transport Plan for 2018-2029 – such an enormous project takes time – and should bring the people and businesses of Norway’s rugged west coast closer together and closer to the centres of manufacture, commerce and social infrastructure of the rest of the country. It’s hoped the development will have a very positive impact on businesses, industries and the workforce. In order to achieve that, the route will replace ferries with bridges and tunnels. The first such project is at Rogfast, with the construction of a 26.7-kilometre subsea road tunnel – longest and deepest sub-sea road tunnel in the world – that will obviate the need for a ferry. It is a massive project, the tunnel reaching a depth of 392 metres, and it’s cost-limited to NOK 16.8-billion (€1.7-billion). Work began in December 2017 and is scheduled for completion in 2025-2026. It should cut the journey time between Stavanger and Bergen by around 40 minutes. It’s hoped it will also facilitate an expansion in both the housing and labour markets in the area. Meanwhile, a new bridge that crosses the Hardangerfjord, south of Bergen, opened in 2013 and is already making journeys between Odda and Voss easier and faster, as well as between Bergen and Hardanger. It means journeying without the need for ferries over a popular and much-admired fjord; tourist coaches almost invariably stop near it to allow holidaymakers to take photographs. It is a photogenic bridge in a highly photogenic landscape and it has replaced the ferry on highway 7/13 between Bruravik and Brimnes. Meanwhile a new main road is to be built between Os and Bergen, starting in the south at Svegatjørn and continuing north to Rådal in Bergen. The overall project includes a new county road from the junction with the Endelausmarka to Lysekloster road.

Fjords, of course, are very picturesque, and draw a great many visitors. However, as any quick glance at a map of Norway would show, they make overland travel along the country’s west coast time-consuming and, for those in a hurry, tedious. They are the reason that Norway’s Norse warriors became such skilled and sometimes dangerous seafarers, feared throughout Europe, even though they were principally traders. They sailed quickly and with skill; if they hadn’t been able to their world would have shrunk to just their own village or township. Learning how to navigate the fjords opened up the world to them. The ruggedness of that coastline is even celebrated in Norway’s national anthem, “Ja, vi elsker dette landet” (Yes, we love this country):

Ja, vi elsker dette landet, Yes, we love this country,

Som det stiger frem, As it rises forth,

Furet, værbitt over vannet, Rugged, storm-scarred oe’r the ocean,

Med de tusen hjem, – With her thousand homes, –

Elsker, elsker det og tenker Love her, in our hearts recalling

På vår far og mor Those who gave us birth

Og den saganatt som senker And old tales, which night recalling

Drømmer på vår jord. Brings as dreams to earth.

The words come from a poem written by the great Norwegian Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson in the 1860s, and my English version here is supposedly an ‘artistic’ translation. It makes more sense in English that way, however, than does the literal translation. Bjørnson is generally regarded as one of Norway’s four greatest-ever poets, the others being Henrik Ibsen, Jonas Lie and Alexander Kielland.

Needless to say, with so many fjords, great and small, to negotiate, developing the E39 is a long-term goal, engaging a lot of new technology to overcome the distance and the great many fjords. The Stortinget has organised research into technological solutions but also it has instigated detailed studies of the environmental aspects of construction, operation and maintenance. Norway is keen for the various parts of the construction to produce their own energy if possible, as well as providing the means for electric vehicles to recharge their batteries. The project has also been designed to use a new type of contract for those working on the project to make the implementation effective and, in the Stortinget’s words, to “exploit available competences”.

ORGANISATIONAL CHALLENGE

In organisational terms, such a huge project would seem to present the scope for a very complicated administration, but Norway has streamlined that, too. A steering committee has been set up, chaired by the Director-General of the Norwegian Public Roads Administration. Also on the committee are the Director of Construction, the Director of Technology and Development and Director of Transport and Society, alongside the Head of the Director General’s Staff and one more staff member in the Directorate of Public Roads. Planning and building of the various projects along the E39 is being managed by the regions through which the road passes. There is careful oversight, too, of such a long-running project, through a reference group, with the Norwegian Public Road Administration (NPRA) holding meetings once or twice each year with the County Mayors of Trøndelag, Agder and Vestland. This is seen as an information channel and an opportunity for local politicians to report to the NPRA and make observations and recommendations.

manager for the Coastal Highway

Route E39, Kjersti Dunham will be

working in Norconsult

Project manager Tore Askeland is in overall charge of seven sub-projects: Strategies; Implementation, Planning and Construction; Social Impact; Fjord Crossings; Risk Management and Technology Qualification; Sustainable Infrastructure; and Implementation Strategies and Contract Types. With a PhD in Risk Management and a Masters in Civil Engineering Technology, both from Stavanger University, he seems a sensible choice. He also has leadership experience with the Norwegian military. He will need it: the Coastal Highway Route E39 project is the largest infrastructure project in modern Norwegian history and could well be the largest ongoing road project in the world. It is such a huge project that the completion date may be as late as 2050. It pays to look ahead but in a realistic way. The great Norwegian playwright Henrik Ibsen wrote in The Master Builder: “Castles in the air – they are so easy to take refuge in. And easy to build, too.” Ibsen would have approved of the E39 project: it’s certainly not just a castle in the air.

Making the E39 a quicker, easier road to get along isn’t just a way of speeding things up. With the harsh weather conditions Norway often faces, the current route is unpredictable, too. Too often up until now the road and those linking to it have been closed and the ferries cancelled because of snow, strong winds or high waves. It’s seen as vital in a modern world for the E39 to be accessible every day of the year and at every hour of the day, with fixed links between islands and the mainland. When completed, it should make life much more comfortable, convenient and predictable for the one third or so of Norway’s 5.3-million population who live along the western coast. It should also help to attract additional tourists and make it far easier to transport freight, an important consideration when up to 60% of Norway’s export goods are produced on the west coast. The planners believe that, when completed, the improved route may change patterns of habitation as what are currently hard-to-reach areas without easy access to hospitals and other vital infrastructure become more accessible. After all, the E39 continues to Denmark, so it is the country’s essential lifeline with southern Europe, too. The cost – NOK 340-billion (more than €34-billion) – is well justified.

© Courtesy Norwegian Public Roads Administration, Vianova PT A/S and Baezeni Co., Ltd

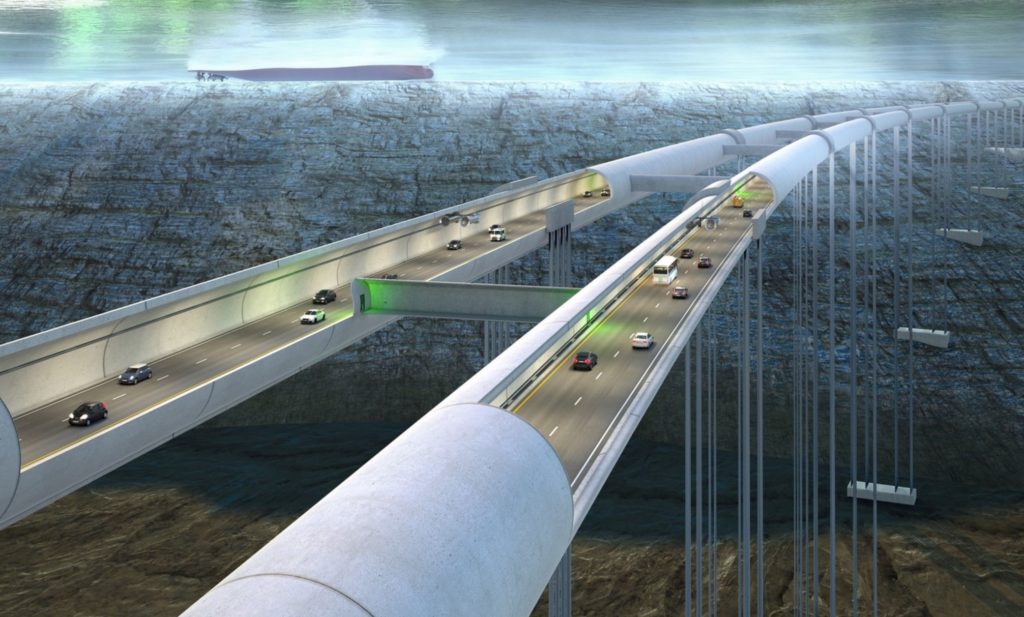

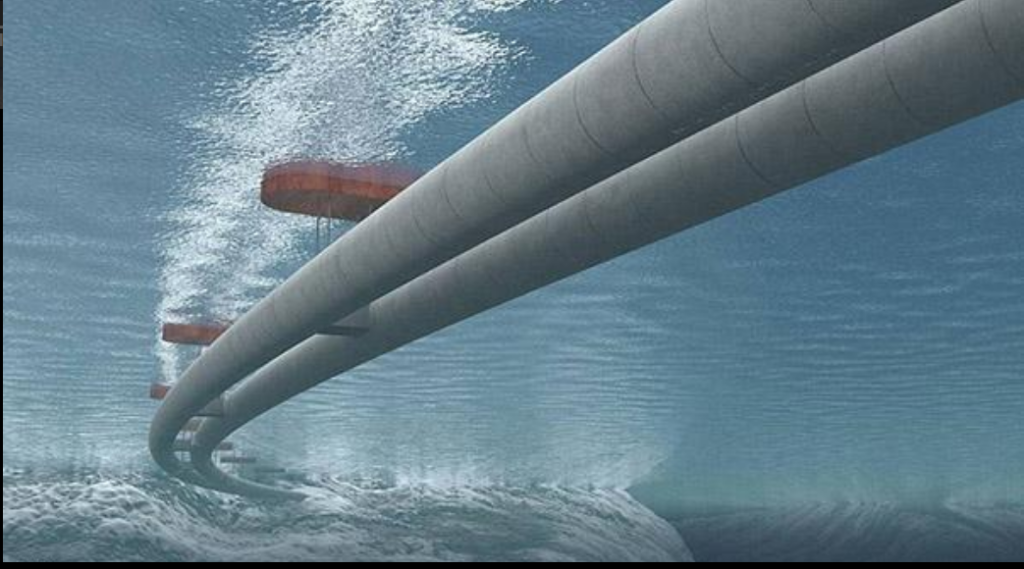

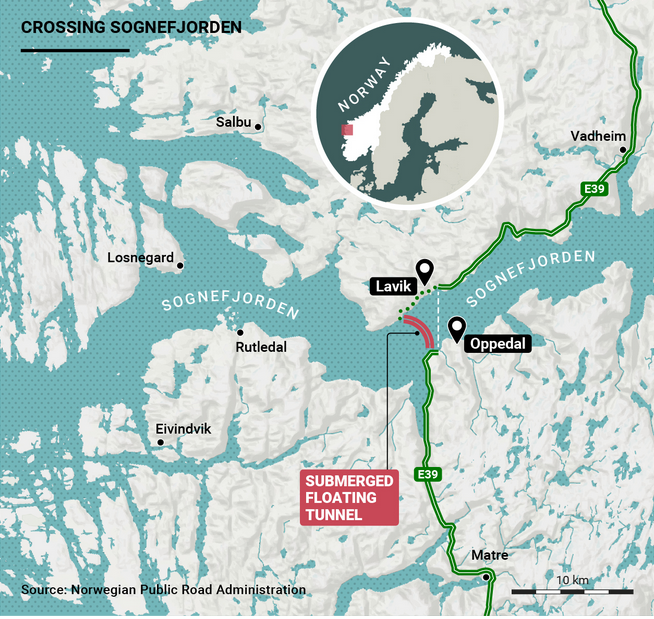

New technology is being considered for the project as ferries give way to bridges and tunnels. One idea being examined is the use of what is called a “Submerged Floating Tube Bridge (SFTB)” for some of the deepest and longest fjords which are especially vulnerable to extreme weather conditions, and where suspension bridges or floating bridges would be difficult to build. When a fjord is more than a few hundred metres deep or wider than two or three kilometres, existing engineering solutions won’t work. In these cases, the seabed would be too deep for traditional rock-bored tunnels because the approach roads would take up too much land.

Floating bridges and other types resting on tension leg platforms can be suitable for deep crossings but they are also worryingly susceptible to harsh weather, such as strong waves and currents. SFTBs get around these problems by reducing the main sea load: the tube would be placed under the water, sufficiently deep to avoid being a hazard to water-borne traffic – usually around 20 to 50 metres – but not so deep that it creates problems with water pressure. Vertical stability would be provided by anchoring the tube to the seabed or to floating pontoons. Tests are being carried out on the system, including on what sort of driver experience they provide, as well ensuring safety in the event of a fire or explosion. There is always the risk of a truck carrying explosive materials catching fire in a tunnel and an SFTB would be a world first: it’s very new technology, although the idea was first put forward in 1886 by the British naval architect, Sir James Edward Reed. Norwegian engineers have been studying the idea since 1923, and several other countries are now considering such structures because of difficulties with more traditional types of construction. The Norwegian Public Road Administration is in talks with some of them with a view more to collaboration than competition, although some of those involved with the E39 have admitted it would be a bit of a coup to be the first to build one. Some of the fjords currently being studied for the possible use of SFTBs are among the longest and deepest in Norway.

This massive construction undertaking involves a number of research projects that could be very useful for other countries in different parts of the world. They include how to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, wind measurements, electric infrastructure that reduces the use of fuels (Norway is the country with the world’s highest rate of electric vehicle usage), intelligent transport systems, the use of solar technology to ensure ice-free road surfaces in winter, and protection against both corrosion and the microbiological degradation of concrete, to name but a few. Three of the largest and most prestigious universities in the Nordic region are involved: the Norwegian University of Science and Technology, the University of Stavanger and Chalmers University of Technology. Altogether, some fifty PhD candidates are engaged in solving the various engineering challenges that the upgrading of the E39 presents.

The Stortinget’s aim is to have the E39 as a continuous Coastal Highway: no ferries, no interruptions, just one continuous road between the two ends, unaffected by having to get across the frequent inlets. Take a look at a map of Norway and see how rugged that west coast is with over a thousand fjords. If you count the Svalbard Islands, the number climbs to around 1,190. And in addition to sorting out the fjord problem with innovative bridges and tunnels, urban roads along the route are being improved, too. It’s all change in Norway: today’s Norwegians will soon be able to get about their country in ways their Norse ancestors could not have dreamed of and the revamped E39 could find itself attracting tourists in much the same way as America’s Route 66.

Anthony James

Click here to read 2020 February’s edition of Europe Diplomatic Magazine